Drug Therapy in Older Adults

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially

Table 2. 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults Strength of Organ System/ Recommendat Quality of Recomm Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Rationale ion Evidence endation References Anticholinergics (excludes TCAs) First-generation antihistamines Highly anticholinergic; Avoid Hydroxyzin Strong Agostini 2001 (as single agent or as part of clearance reduced with e and Boustani 2007 combination products) advanced age, and promethazi Guaiana 2010 Brompheniramine tolerance develops ne: high; Han 2001 Carbinoxamine when used as hypnotic; All others: Rudolph 2008 Chlorpheniramine increased risk of moderate Clemastine confusion, dry mouth, Cyproheptadine constipation, and other Dexbrompheniramine anticholinergic Dexchlorpheniramine effects/toxicity. Diphenhydramine (oral) Doxylamine Use of diphenhydramine in Hydroxyzine special situations such Promethazine as acute treatment of Triprolidine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate. Antiparkinson agents Not recommended for Avoid Moderate Strong Rudolph 2008 Benztropine (oral) prevention of Trihexyphenidyl extrapyramidal symptoms with antipsychotics; more effective agents available for treatment of Parkinson disease. Antispasmodics Highly anticholinergic, Avoid Moderate Strong Lechevallier- Belladonna alkaloids uncertain except in Michel 2005 Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide effectiveness. short-term Rudolph 2008 Dicyclomine palliative Hyoscyamine care to Propantheline decrease Scopolamine oral secretions. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* May -

Potentially Harmful Drugs in the Elderly: Beers List

−This Clinical Resource gives subscribers additional insight related to the Recommendations published in− March 2019 ~ Resource #350301 Potentially Harmful Drugs in the Elderly: Beers List In 1991, Dr. Mark Beers and colleagues published a methods paper describing the development of a consensus list of medicines considered to be inappropriate for long-term care facility residents.12 The “Beers list” is now in its sixth permutation.1 It is intended for use by clinicians in outpatient as well as inpatient settings (but not hospice or palliative care) to improve the care of patients 65 years of age and older.1 It includes medications that should generally be avoided in all elderly, used with caution, or used with caution or avoided in certain elderly.1 There is also a list of potentially harmful drug-drug interactions in seniors, as well as a list of medications that may need to be avoided or have their dosage reduced based on renal function.1 This information is not comprehensive; medications and interactions were chosen for inclusion based on potential harm in relation to benefit in the elderly, and availability of alternatives with a more favorable risk/benefit ratio.1 The criteria no longer address drugs to avoid in patients with seizures or insomnia because these concerns are not unique to the elderly.1 Another notable deletion is H2 blockers as a concern in dementia; evidence of cognitive impairment is weak, and long-term PPIs pose risks.1 Glimepiride has been added as a drug to avoid. Some drugs have been added with cautions (dextromethorphan/quinidine, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole), and some have had cautions added (rivaroxaban, tramadol, SNRIs). -

Effect of Beers Criteria on Healthcare Utilization and Cost in Community-Dwelling Elderly Patients

Medical University of South Carolina MEDICA MUSC Theses and Dissertations 2018 Effect of Beers Criteria on Healthcare Utilization and Cost in Community-Dwelling Elderly Patients Courtney O'Neill Roldan Medical University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://medica-musc.researchcommons.org/theses Recommended Citation Roldan, Courtney O'Neill, "Effect of Beers Criteria on Healthcare Utilization and Cost in Community- Dwelling Elderly Patients" (2018). MUSC Theses and Dissertations. 294. https://medica-musc.researchcommons.org/theses/294 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by MEDICA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MUSC Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of MEDICA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EFFECT OF BEERS CRITERIA ON HEALTHCARE UTILIZATION AND COST IN COMMUNITY-DWELLING ELDERLY PATIENTS by Courtney O’Neill Roldan, MHA A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Medical University of South Carolina in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Health Professions © Courtney O’Neill Roldan 2018 All Rights Reserved Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge my dissertation committee chair Dr. Kit Simpson, and committee members Dr. Annie Simpson, Dr. William Moran, and Dr. David Taber for their guidance throughout this study. Without their unending service and expertise this project would not have been successful. Not only did Dr. Kit Simpson provide the data for this study, but she also introduced me to Beers Criteria many months before this project came to fruition. I am especially grateful for Dr. Kit Simpson’s mentorship that enabled me to preserve through this project, Dr. -

NSG0315 CE Insomnia Yogesh.Indd

2.5 2.5 ANCC PHARM CONTACT CONTACT HOURS HOURS 38 l Nursing2015 l March www.Nursing2015.com Copyright © 2015 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved. Pharmacology for insomnia: Consider the options By Jamie M. Rosini, PharmD, BCPS, and Pooja Dogra, PharmD, BCACP, CDE INSOMNIA IS POOR SLEEP quality, defined as difficulty initiating and/ or maintaining sleep or waking up too early despite adequate sleep op- portunity, which then interferes with daytime functioning.1,2 Consid- ered the most common sleep disorder, insomnia affects approximately 60 million Americans annually.3 To care for patients suffering from insomnia, clinicians must first thoroughly assess their sleep habits, identifying and addressing under- lying conditions that may contribute to insomnia such as depression, emotional stress, sleep apnea, or substance abuse. Patients should also be counseled about sleep hygiene, stimulus control, and behavioral approaches to improving the quality of sleep. (See Helping improve a patient’s sleep hygiene.) If indicated, the healthcare provider may then add a medication to the treatment regimen for a limited period. The choice of medication is based on many factors, including the type of insomnia (difficulty falling asleep, staying asleep, or both).3,4 (See Classifying insomnia types.) This article provides an overview of agents commonly used to treat insomnia, including prescription drugs, over-the-counter (OTC) medi- cations, and herbal or dietary products. By understanding how and why certain medications help treat insomnia, nurses can help patients use them safely to get a good night’s sleep. Unless otherwise specified, the following information applies to adults, not children. -

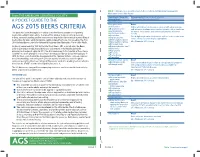

Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults

TABLE 1. 2015 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults From THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY Organ System, Therapeutic Recommendation, Rationale, Quality of Evidence Category, Drug(s) (QE), Strength of Recommendation (SR) A POCKET GUIDE TO THE Anticholinergics First-generation Avoid antihistamines: Highly anticholinergic; clearance reduced with advanced age, AGS 2015 BEERS CRITERIA ■ Brompheniramine and tolerance develops when used as hypnotic; risk of confusion, ■ Carbinoxamine This guide has been developed as a tool to assist healthcare providers in improving dry mouth, constipation, and other anticholinergic effects or ■ Chlorpheniramine toxicity medication safety in older adults. The role of this guide is to inform clinical decision- ■ Clemastine Use of diphenhydramine in situations such as acute treatment of ■ making, research, training, quality measures and regulations concerning the prescribing of Cyproheptadine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate medications for older adults to improve safety and quality of care. It is based on The AGS ■ Dexbrompheniramine QE = Moderate; SR = Strong 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. ■ Dexchlorpheniramine ■ Dimenhydrinate Originally conceived of in 1991 by the late Mark Beers, MD, a geriatrician, the Beers ■ Diphenhydramine (oral) Criteria catalogues medications that cause side effects in the elderly due to the ■ Doxylamine physiologic changes of aging. In 2011, the AGS -

Beers Criteria Printable Pocketcard

Table 1 (continued from page 1) TABLE 1: 2012 AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults AGS BEERS CRITERIA Organ System/ Recommendation, Rationale, FOR POTENTIALLY INAPPROPRIATE Therapeutic Category/Drug(s) Quality of Evidence (QE) & Strength of Recommendation (SR) Antispasmodics Avoid except in short-term palliative care to decrease MEDICATION USE IN OLDER ADULTS n Belladonna alkaloids oral secretions. n Clidinium-chlordiazepoxide FROM THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY n Dicyclomine Highly anticholinergic, uncertain effectiveness. n Hyoscyamine This clinical tool, based on The AGS 2012 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older n Propantheline QE = Moderate; SR = Strong Adults (AGS 2012 Beers Criteria), has been developed to assist healthcare providers in improving medication safety in n Scopolamine older adults. Our purpose is to inform clinical decision-making concerning the prescribing of medications for older adults in order to improve safety and quality of care. Antithrombotics Dipyridamole, oral short-acting* (does not Avoid. Originally conceived of in 1991 by the late Mark Beers, MD, a geriatrician, the Beers Criteria catalogues medications apply to the extended-release combination with May cause orthostatic hypotension; more effective alternatives that cause adverse drug events in older adults due to their pharmacologic properties and the physiologic changes of aspirin) available; IV form acceptable for use in cardiac stress testing. aging. In 2011, the AGS undertook an update of the criteria, assembling a team of experts and funding the develop- QE = Moderate; SR = Strong ment of the AGS 2012 Beers Criteria using an enhanced, evidence-based methodology. Each criterion is rated (qual- Ticlopidine* Avoid. -

American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria For

CLINICAL INVESTIGATIONS American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults By the American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel older adults is one strategy to decrease the risk of adverse The 2015 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria events. Interventions using explicit criteria have been are presented. Like the 2012 AGS Beers Criteria, they found to be an important component of strategies for – include lists of potentially inappropriate medications to be reducing inappropriate medication usage.3 5 avoided in older adults. New to the criteria are lists of The AGS Beers Criteria for PIM Use in Older Adults select drugs that should be avoided or have their dose are one of the most frequently consulted sources about the adjusted based on the individual’s kidney function and safety of prescribing medications for older adults. The select drug–drug interactions documented to be associated AGS Beers Criteria are used widely in geriatric clinical with harms in older adults. The specific aim was to have a care, education, and research and in development of qual- 13-member interdisciplinary panel of experts in geriatric ity indicators. In 2011, the AGS assumed the responsibility care and pharmacotherapy update the 2012 AGS Beers of updating and maintaining the Beers Criteria and, in Criteria using a modified Delphi method to systematically 2012, released the first update of the criteria since 2003. review and grade the evidence and reach a consensus on The AGS has made a commitment to update the criteria each existing and new criterion. The process followed an regularly. -

American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® For

CLINICAL INVESTIGATION ® American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults ® By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel* ® For the 2019 update, an interdisciplinary expert panel The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria ® reviewed the evidence published since the last update (AGS Beers Criteria ) for Potentially Inappropriate Medica- (2015) to determine if new criteria should be added or if tion (PIM) Use in Older Adults are widely used by clini- existing criteria should be removed or undergo changes to cians, educators, researchers, healthcare administrators, and their recommendation, rationale, level of evidence, or regulators. Since 2011, the AGS has been the steward of the strength of recommendation. Each of the five types of cri- criteria and has produced updates on a 3-year cycle. The ® teria in the 2015 update were retained in this 2019 update: AGS Beers Criteria is an explicit list of PIMs that are typi- medications that are potentially inappropriate in most older cally best avoided by older adults in most circumstances or adults, those that should typically be avoided in older under specific situations, such as in certain diseases or con- adults with certain conditions, drugs to use with caution, ditions. For the 2019 update, an interdisciplinary expert drug-drug interactions, and drug dose adjustment based on panel reviewed the evidence published since the last update kidney function. (2015) to determine if new criteria should be added or if existing criteria should be removed or undergo changes to their recommendation, rationale, level of evidence, or OBJECTIVES strength of recommendation. -

Aging Physiology, Pharmacokinetics & Pharmacodynamics

1 AGING PHYSIOLOGY, PHARMACOKINETICS & PHARMACODYNAMICS Linda Sobeski, PharmD, BCPS Clinical Assistant Professor UNMC College of Pharmacy May 5, 2020 Updated: 3/2020 Updated: 4/2018 2 HRSA Statement This program is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $749,926 with 0% financed with non- governmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov. 3 Objectives 1. Describe the physiologic, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic factors which affect drug use in the elderly 2. Describe risk factors and identify drugs commonly associated with adverse drug events in the elderly 3. Recognize potentially inappropriate drug use and recommend alternative therapy where appropriate 4. Discuss principles of optimal prescribing for older patients 4 Challenges of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy • Impact of aging physiology on drug therapy • Pharmacokinetics • Pharmacodynamics • Polypharmacy • Inappropriate prescribing (Beers, and others) • Adverse drug events • Medication adherence 5 Effects of Aging on Absorption • Passive diffusion: unchanged • No change in overall F of most drugs • Decreased GI motility & blood flow counterbalanced by increased drug transit time & increased time for absorption • Active transport: • Decreased F for some drugs: ions, vitamins (e.g. B12), minerals (e.g. Fe2+, Ca2+) • Ca2+ in the setting of increased GI pH • First pass extraction: • Decreased hepatic blood flow • Increased F for high extraction drugs: e.g. TCAs, methylphenidate, propranolol, NTG • Slowed or reduced activation of produgs: e.g. -

Q&A Summary Chronic Insomnia in Older Adults

RxFiles: Q&A Summary www.RxFiles.ca ‐ Oct 2013 Debbie Bunka Chronic Insomnia in Older Adults Sleep patterns naturally change as one gets older. Insomnia in long‐term care settings10 1,2,3 Compared to younger people, older adults: • Difficult to treat insomnia in this setting due to staff providing • Sleep fewer hours & take longer to fall asleep routine care that can affect sleep (turning bed‐bound residents • Wake up more often during the night & are more easily every 2 hours, checking incontinent residents periodically at night, disturbed by light, noise, pain, etc… early morning vital sign measurements, etc.) • May not adapt as quickly to changes, such as a new bed • Other problems: many residents have a roommate, doubling the • Have changes in their sleep cycle, e.g. older adults spend less interruptions. Residents may have little ability to make time in the most restful stage of sleep (less deep sleep) behavioural modifications given the environment. ÖResult: tend to experience ↑ daytime sleepiness • Efforts to ↓ interruptions & noise in this setting, as well as a commitment to ↑ daytime activities, avoid daytime naps & 4,5 What is chronic insomnia? difficulty falling asleep, staying minimize time awake in bed for residents would help reduce use asleep, waking up too early, or sleep that is non‐restorative. of sedatives in older, frail adults prone to adverse effects. Sleep difficulty, lasting ≥ 1 month 3 nights/week, occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep. Insomnia is clinically relevant Approach to insomnia treatment • Non‐pharmacological methods are essential for long‐term if associated with significant distress or daytime impairment 11 (fatigue, mood, cognitive, social/work dysfunction, etc…) success (~75% of those treated will benefit ). -

AGS 2019 BEERS Pocket-PRINTABLE.Indd

TABLE 1. 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults From THE AMERICAN GERIATRICS SOCIETY Organ System, Therapeutic Recommendation, Rationale, Quality of Evidence Category, Drug(s) (QE), Strength of Recommendation (SR) A POCKET GUIDE TO THE Anticholinergics * First-generation Avoid ® antihistamines: Highly anticholinergic; clearance reduced with advanced age, 2019 AGS BEERS CRITERIA ■ Brompheniramine and tolerance develops when used as hypnotic; risk of confusion, This guide has been developed as a tool to assist healthcare providers in improving ■ Carbinoxamine dry mouth, constipation, and other anticholinergic effects or medication safety in older adults. The role of this guide is to inform clinical decision- ■ Chlorpheniramine toxicity making, research, training, quality measures and regulations concerning the prescribing of ■ Clemastine Use of diphenhydramine in situations such as acute treatment of ■ medications for older adults to improve safety and quality of care. It is based on The 2019 Cyproheptadine severe allergic reaction may be appropriate ■ Dexbrompheniramine AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. ■ Dexchlorpheniramine QE = Moderate; SR = Strong Originally conceived of in 1991 by the late Mark Beers, MD, a geriatrician, the Beers ■ Dimenhydrinate Criteria catalogues medications that cause side effects in older adults due to the ■ Diphenhydramine (oral) physiologic changes of aging. In 2011, the AGS sponsored its first update of the criteria, ■ Doxylamine assembling a team of experts and using an enhanced, evidence-based methodology. ■ Hydroxyzine Since 2011, the AGS has been the steward of the criteria and has produced updates ■ Meclizine using an evidence-based methodology and rating each Criterion (quality of evidence ■ Promethazine and strength of evidence) using the American College of Physicians’ Guideline Grading ■ Pyrilamine System, which is based on the GRADE scheme developed by Guyatt et al. -

American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers

CLINICAL INVESTIGATION ® American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults ® By the 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel* ® For the 2019 update, an interdisciplinary expert panel The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria ® reviewed the evidence published since the last update (AGS Beers Criteria ) for Potentially Inappropriate Medica- (2015) to determine if new criteria should be added or if tion (PIM) Use in Older Adults are widely used by clini- existing criteria should be removed or undergo changes to cians, educators, researchers, healthcare administrators, and their recommendation, rationale, level of evidence, or regulators. Since 2011, the AGS has been the steward of the strength of recommendation. Each of the five types of cri- criteria and has produced updates on a 3-year cycle. The ® teria in the 2015 update were retained in this 2019 update: AGS Beers Criteria is an explicit list of PIMs that are typi- medications that are potentially inappropriate in most older cally best avoided by older adults in most circumstances or adults, those that should typically be avoided in older under specific situations, such as in certain diseases or con- adults with certain conditions, drugs to use with caution, ditions. For the 2019 update, an interdisciplinary expert drug-drug interactions, and drug dose adjustment based on panel reviewed the evidence published since the last update kidney function. (2015) to determine if new criteria should be added or if existing criteria should be removed or undergo changes to their recommendation, rationale, level of evidence, or OBJECTIVES strength of recommendation.