Original Article Analysis of the Player Market in Central and Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kematian Haringga Sirila Dalam Wacana Pemberitaan Media

JURNAL AUDIENS VOL. 1, NO. 1 (2020): MARCH 2020 https://doi.org/10.18196/ja.1106 Kematian Haringga Sirila dalam Wacana Pemberitaan Media (Analisis Wacana Pemberitaan Kasus Haringga Sirila pada Surat Kabar Jawa Pos, Kompas, dan Republika tanggal 26-30 September 2018) Kurniasari Alifta Ramadhani (Correspondence Author) Program Studi Ilmu Komunikasi, Universitas Muhammadiyah Yogyakarta, Indonesia [email protected] Submitted: 30 November 2019; Revised: 2 March 2020; Accepted: 2 March 2020 Abstract Chaos and riots between Indonesian football supporters was once again causing casualities. Haringga Sirila, a Persija Jakarta supporter, died because of riot between supporters of Persib Bandung and The Jakmania, Persija Jakarta supporters, in Gojek Traveloka League 1 at the Bandung Lautan Api Stadium (GBLA) on September 23, 2018. The death of Haringga Sirila was adding a long list of riot case that occurred between Persib Bandung supporters vs. Persija Jakarta supporters. This research tries to see how the Daily Newspaper of Jawa Pos, Kompas, and Republika were covering on the case of Haringga Sirila's death. The research uses critical discourse analysis methods, specifically the Norman Fairclough model. This study analyzes text, practice of discourse, and practice of sociocultural inside coverage. In the sociocultural situation of this country; the existence of media conglomerates in Indonesia has propagated and influenced the practice of producing texts and news discourses. Thus, the news bias on an event often occurs. In the results of this study, it finds that the discourse rolled out by each media was different even though it reported the same event. This can be seen from the analysis results which show that in the news related to this case, Jawa Pos identified itself with the supporters and clubs of League 1. -

The Effect of the UEFA Champions League Financial Payout System on Competitive Balance in European Soccer Leagues

The Effect of the UEFA Champions League Financial Payout System on Competitive Balance in European Soccer Leagues Nathan A. Vestrich-Shade Advised by: Timothy Lambie-Hanson Senior Thesis in Economics Haverford College April 28, 2016 Abstract The paper examines the effect of UEFA Champions League payouts on competitive balance across European leagues. A league-level specification identifies the magnitude of the effect of the UEFA payouts on three measures of competitive balance. The results confirm that the UEFA payouts have a statistically significant effect at the league-level depending on which competitive balance measure and league sample is used. However, the UEFA payouts had no statistically significant effect on individual clubs’ average annual payroll or the clubs’ qualification for the Champions League in the following season. Nathan Vestrich-Shade Table of Contents Section I: Introduction………………………………………………….........................................3 Section II: Literature Review……………………………………………………………………...4 Section III: Data…………………………………………………………………………………...9 Section IV: Methodology………………………………………………………………………...12 Section V: Results………………………………………………………………………………..15 Section VI: Discussion…………………………………………………………………………...19 Section VII: Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….23 Appendix…………………………………………………………………………………………24 References………………………………………………………………………………………..40 2 Nathan Vestrich-Shade Section I: Introduction Over the years, select clubs in European domestic soccer leagues tend to “control” the spots at the top of the end-of-season -

Olympiacos CFP V Rosenborg BK

Olympiacos CFP v Rosenborg BK Georgios Karaiskakis - Athens Tuesday, 13 September 2005 - 20:45 (CET) Group stage - Group F - Matchday 1 Match officials Referee Stefano Farina (ITA) Assistant referees Andrea Consolo (ITA), Massimo Biasutto (ITA) Fourth official Enrico Rocchi (ITA) UEFA delegate Barry Taylor (ENG) Match preview Olympiacos set greater goals Having gone tantalisingly close to reaching the knockout stages of the UEFA Champions League last season, Olympiacos CFP hope to "show their true colours" this term and progress from the group stage for only the second time in ten attempts. 'Early goal' The Greek champions begin their Group F campaign at home to Rosenborg BK on Tuesday with coach Trond Sollied calling on his side to make an early impression ahead of likely tougher tests against Real Madrid CF and Olympique Lyonnais. "There are 18 points up for grabs in the group and we must take as many as we can from each match," said Sollied, a former Rosenborg coach and player whose last experience of Champions League football was at the helm of Club Brugge KV. "If we can get an early goal [on Tuesday] it will certainly boost our chances." False dawns Olympiacos are well used to false dawns in Europe, although they were unlucky not to advance with their tally of ten points in Group A last season. At half-time on Matchday 6 they led Liverpool FC 1-0, and were still on course for the first knockout round at 2-1 down with four minutes to play when Steven Gerrard struck a stunning winner to propel the English team towards the next stage (and eventual glory) and the Piraeus outfit into the UEFA Cup. -

Bachelor's Thesis

Bachelor’s thesis IDR600 Sport Management Norwegian Football Fans Attendance Case: Norwegian men's football Lars Neerbye Eriksen and Oscar Hesselberg Killingmoe Number of pages including this page: 51 Molde, 02/06-2020 Mandatory statement Each student is responsible for complying with rules and regulations that relate to examinations and to academic work in general. The purpose of the mandatory statement is to make students aware of their responsibility and the consequences of cheating. Failure to complete the statement does not excuse students from their responsibility. Please complete the mandatory statement by placing a mark in each box for statements 1-6 below. 1. I/we hereby declare that my/our paper/assignment is my/our own work, and that I/we have not used other sources or received other help than mentioned in the paper/assignment. 2. I/we hereby declare that this paper Mark each 1. Has not been used in any other exam at another box: 1. department/university/university college 2. Is not referring to the work of others without 2. acknowledgement 3. Is not referring to my/our previous work without 3. acknowledgement 4. 4. Has acknowledged all sources of literature in the text and in the list of references 5. 5. Is not a copy, duplicate or transcript of other work I am/we are aware that any breach of the above will be 3. considered as cheating, and may result in annulment of the examination and exclusion from all universities and university colleges in Norway for up to one year, according to the Act relating to Norwegian Universities and University Colleges, section 4-7 and 4-8 and Examination regulations section 14 and 15. -

New UEFA National Team Coefficient Ranking System 20 May 2008

New UEFA National Team Coefficient Ranking System 20 May 2008 New UEFA National Team Coefficient Ranking System 1. Purpose of the UEFA national team coefficient The UEFA national team coefficient is an important tool for ensuring sporting balance and fairness in both the qualifying and final rounds of the UEFA European Football Championship. It is used in particular for the pot allocation for the qualifying draw and the final draw, and it is therefore crucial that the coefficient system reflects the real strength of each team as best as possible. 2. Current UEFA coefficient system The current UEFA coefficient system is generated according to the results achieved in the most recent qualifying competitions for the UEFA European Football Championship and the FIFA World Cup. The total number of points obtained in the qualifying competitions of both of the aforementioned competitions is divided by the number of matches played and the resulting coefficient is used for the rankings. In the case of an association that qualifies automatically for the final round of one of the competitions in question (as host association), the coefficient is calculated on the basis of its results in its most recent qualifying competition. The system has the advantage of offering a good comparison of the team strengths in the qualifying competitions. In addition, it is transparent and simple to calculate. However, the fact that matches played during final tournaments are not taken into account distorts the rankings significantly and does not reflect reality. 3. New proposed UEFA system 3.1. Cornerstones and principles 3.1.1. Matches taken into consideration All national A-team matches played in UEFA EURO and the FIFA World Cup qualifying competitions and final tournaments are taken into consideration. -

Ponuda 2017-08-26 Prvi Deo.Xlsx

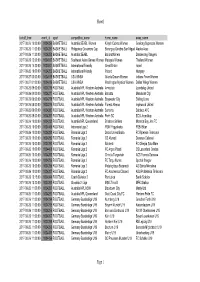

Sheet1 kickoff_time event_id sport competition_name home_name away_name 2017-08-26 10:00:00 1004256 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Women Kilsyth Cobras Women Geelong Supercats Women 2017-08-26 11:00:00 1004257 BASKETBALL Philippines Governors Cup Barangay Ginebra San Miguel Alaska Aces 2017-08-26 11:30:00 1004258 BASKETBALL Australia SEABL Ballarat Miners Dandenong Rangers 2017-08-26 12:00:00 1004617 BASKETBALL Southeast Asian Games Women Malaysia Women Thailand Women 2017-08-26 15:30:00 1004847 BASKETBALL International Friendly Great Britain Israel 2017-08-26 18:00:00 1004259 BASKETBALL International Friendly Poland Hungary 2017-08-27 00:00:00 1004618 BASKETBALL USA WNBA Atlanta Dream Women Indiana Fever Women 2017-08-27 01:00:00 1004619 BASKETBALL USA WNBA Washington Mystics Women Dallas Wings Women 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004276 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Armadale Joondalup United 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004277 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Balcatta Mandurah City 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004278 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Bayswater City Stirling Lions 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004279 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Floreat Athena Inglewood United 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004280 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Sorrento Subiaco AFC 2017-08-26 09:00:00 1004281 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Western Australia Perth SC ECU Joondalup 2017-08-26 10:00:00 1004282 FOOTBALL Australia NPL Queensland Brisbane Strikers Moreton Bay Jets FC 2017-08-26 10:00:00 1004466 FOOTBALL Indonesia Liga 2 PSIM Yogyakarta PSBI Blitar -

Will Asia Lead the Football Industry?

Will Asia lead the football industry? 28 OCTOBER 2019 Simone Centola SPECIAL COUNSEL | SINGAPORE CATEGORY: ARTICLE With its young and growing population of four billion people and an ever-increasing group of football fans, Asia is considered the next frontier of football. Asia is increasingly attracting players and managers as well as major European clubs, to catch opportunities and explore its potential for global expansion. Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal, Barcelona, Real Madrid, Juventus and Paris Saint-Germain have huge followings and have established regional ofces. More clubs are planning to set up regional bases and are regularly scouting opportunities in Asia. With Japan, South Korea and Australia being the most mature markets in Asia Pacic, Chinese football is set to grow by leveraging on Beijing’s renewed support. The economic rise of ASEAN (the Association of ten South Asian nations) is having a knock-on effect on the development of local leagues, with the rebranded Liga 1 in Indonesia, Philippines Football League, Singapore Premier League and V.League 1 in Vietnam topping the list of best developing leagues. Spanish La Liga, for example, said to be targeting to double its viewership in Asia by 2020, has an ofce in Malaysia and is co- operating with the Malaysian League to develop a local industry. The Malaysian and Philippines leagues have been recently privatised. The gradual increase of intra-Asian transfer of players/managers within some leagues, as well as Asian and non-Asian investors developing commercial ventures in football, may be a contributing factor. Asian investments into European football are also set to increase, encouraged by current favourable factors and several precedents such as Leeds, Atletico Madrid, Real Madrid, and Inter Milan are likely to inspire more acquisitions, investments and sponsorship deals from Asia. -

GKS Katowice Fans’ Complaints to UEFA Which Saved Their Club

Everything FEATURES: you need to know about every . The money, personalities Ekstraklasa club - managers, and players of the Polish players, statistics, star names, game fans' views and much more! . Stadiums: after the Euros, what now? Struggles in the Champions . League . Polonia - the biggest mess in Europe INTERVIEWS: . Kibu Vicuna . James Sinclair . Ben Starosta . Paweł Abbott I N A S S O C I A T I O N W I T H #EKSTRAKLASA - CLUBS #EKSTRAKLASA - CLUBS CREDITS #EKSTRAKLASA MAGAZINE zLazienkowskiej.blogspot.com The Team Editor: Michał Zachodny - polishscout.blogspot.com - Twitter: @polishscout Co-editor: Ryan Hubbard - EKSTRAKLASAreview.co.uk - Twitter: @Ryan_Hubbard Graphics/Design: Rafał Tromczyński - flavors.me/traanZ - Twitter: @Tromczynski Writer/Contributor: Andrzej Gomołysek - taktycznie.net - Twitter: @taktycznie Writer/Contributor: Marcus Haydon - Twitter: @marcusjhaydon Writer: Jakub Krzyżostaniak - www.lechinusa.com - Twitter: @KubaLech Writer: Tomasz Krzyżostaniak - www.lechinusa.com - Twitter: @TKLech Writer: Jakub Olkiewicz - Twitter: @JOlkiewicz Proof-reader: Lucas Wilk - Twitter: @LucasWilk Proof-reader: Simon Rees - Twitter: @simonrees73 Proof-reader: Matthew Joseph - Twitter: @elegantgraffiti #EKSTRAKLASA - EDITORS #EKSTRAKLASA - EDITORS Editor’s view Editor’s view Ryan Hubbard Michał Zachodny EKSTRAKLASAreview.co.uk PolishScout.blogspot.com Isn’t it interesting what a summer can do for a country’s image? Just a few months ago people were clamour- If one word could fully describe what kind of league Ekstraklasa really is then „specific” is the only answer. ing, led in part by the BBC, to criticise Poland and their footballing authorities for “widespread racism and Why? Well, this is exactly why we decided to take the challenge of preparing this magazine for you. -

Performa Teknik Sepakbola Pemain Bali United Di Liga 1 Tahun 2019

PERFORMA TEKNIK SEPAKBOLA PEMAIN BALI UNITED DI LIGA 1 TAHUN 2019 TUGAS AKHIR SKRIPSI Diajukan kepada Fakultas Ilmu Keolahragaan Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta untuk Memenuhi Sebagian Persyaratan Guna Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Oleh: Ahmad Mundir 14602241024 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN KEPELATIHAN OLAHRAGA FAKULTAS ILMU KEOLAHRAGAAN UNIVERSITAS NEGERI YOGYAKARTA 2020 ii SURAT PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Ahmad Mundir NIM : 14602241024 Program Studi : Pendidikan Kepelatihan Judul TAS : Performa Teknik Sepakbola Pemain Bali United Di Liga 1 Tahun 2019 Menyatakan bahwa skripsi ini benar benar karya saya sendiri *). Sepanjang pengetahuan saya tidak terdapat karya atau pendapat yang ditulis atau diterbitkan orang lain kecuali sebagai acuan kutipan dengan mengikuti tata penulisan karya ilmiah yang telah lazim. Yogyakarta, 29 Juni 2020 Yang Menyatakan, Ahmad Mundir 14602241024 iii iv MOTTO 1. Jangan pernah menyerah, tetaplah berusaha untuk mencoba, tidak akan ada orang sukses saat ini jika setiap kegagalan dan kesulitan selalu diakhiri dengan menyerah. 2. Bukan kebahagiaan yang menjadikan kita bersyukur, tapi bersyukurlah yang membuat kita bahagia. v PERSEMBAHAN Alhamdulillah, segala puji syukur bagi Allah SWT Tuhan semesta alam, Engkau berikan berkah dari buah kesabaran dan keikhlasan dalam mengerjakan Tugas Akhir Skripsi ini sehingga dapat selesai tepat pada waktunya. Karya ini saya persembahkan kepada: 1. Kedua orang tua saya Bapak M Huda dan Ibu Fatayati yang sangat saya sayangi, yang selalu mendukung dan mendoakan setiap langkah saya sebagai anaknya. 2. Keluaraga dan sahabat saya yang selalu memberikan semangat dan memberi doa atas skripsi ini. vi PERFORMA TEKNIK SEPAKBOLA PEMAIN BALI UNITED DI LIGA 1 TAHUN 2019 Oleh: Ahmad Mundir 14602241024 ABSTRAK Penelitian ini dilatarbelakangi oleh masih banyaknya teknik yang salah yang dilakukan pemain bali united di liga 1 tahun 2019. -

Managing the Project of Forming a Regional Football League

European Project Management Journal, Volume 7, Issue 2, December 2017 MANAGING THE PROJECT OF FORMING A REGIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE Tamara Tomovi ć1, Marko Mihi ć2 1Football Association of Belgrade, Serbia 2Faculty of Organizational Sciences, University of Belgrade, Serbia Abstract: The subject of this research is a practical implementation of the project management in the process of founding a sports organization for managing sports events such is a football league and in a process of forming a regional football league. Therefore, this research will present theoretical framework and organizational approaches in project management and management in sports, whereas basic project phases will be elaborated through sports aspects. Furthermore, the specific features of project management in sports and organizational structure of football associations will be particularized in order to offer an insight into a possibility of positioning new football organization with an aim to form and manage a regional league. Taking into the account all the specifics of the sport and project management, the aim of this research is to offer an idea of forming a regional football league, and furthermore, to impose the necessity of founding an independent and impartial organization which will manage cited league. Key words: management, management in sports, project management, football, regional football league 1. INTRODUCTION renewal of countries and the improvement of the quality of life in them. With the The golden age of Serbian football was revitalization ofall spheres of everyday life unexpectedly broken by the breakdown of the began the renewal of football as a significant Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia integrative factor. The renewal happened (SFRY) in 1992. -

Football Clubs' Valuation: the European Elite 2019

The European Elite 2019 Football Clubs’ Valuation May, 2019 KPMG Sports Advisory Practice footballbenchmark.com © 2019 KPMG Advisory Ltd., a Hungarian limited liability company and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. What is KPMG Football Benchmark? A business intelligence tool enabling relevant comparisons with competitors, including: Club finance & operations A consolidated and verified database of the financial and operational performance of over 200 football clubs, both in Europe and South America. Social media analytics A historical tracking of the social media activity of hundreds of football clubs and players. Player valuation A proprietary algorithm, which calculates the market value of 4,700 football players from nine European and two South American leagues. © 2019 KPMG Advisory Ltd., a Hungarian limited liability company and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International ”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Football Clubs’ Valuation: The European Elite 2019 03 Table of contents 04 05 Foreword Selection criteria 06 16 Headline fndings Squad and player valuation - impact on EV 24 26 Enterprise Value Our methodology ranges & mid points © 2019 KPMG Advisory Ltd., a Hungarian limited liability company and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. 04 Football Clubs’ Valuation: The European Elite 2019 Foreword Dear Reader, Following the success of the past three years, I am delighted to introduce you to KPMG’s fourth edition of the club valuation report, an annual analysis providing an indication of the Enterprise Value (EV) of the 32 most prominent European football clubs as at 1 January 2019. -

Introducing Financial Derivatives Into Football Transfer Markets

NATIONAL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS SCHOOL OF APPLIED MATHEMATICAL AND PHYSICAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS INTERDISCIPLINARY POSTGRADUATE SPECIALIZATION PROGRAMME “MATHEMATICAL MODELING IN MODERN TECHNOLOGIES AND FINANCIAL ENGINEERING” Introducing Financial Derivatives into Football Transfer Markets MASTER THESIS Stavros Vatikiotis Supervisors : Dr. Athanasios Triantafyllou Dr. Apostolos Mintzelas Lecturer, University of Essex KPMG Greece Athens, June 2019 NATIONAL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF ATHENS SCHOOL OF APPLIED MATHEMATICAL AND PHYSICAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS INTERDISCIPLINARY POSTGRADUATE SPECIALIZATION PROGRAMME “MATHEMATICAL MODELING IN MODERN TECHNOLOGIES AND FINANCIAL ENGINEERING” Introducing Financial Derivatives into Football Transfer Markets Stavros Vatikiotis Supervisors : Dr. Athanasios Triantafyllou Dr. Apostolos Mintzelas Lecturer, University of Essex Approved by the three-member committee ................................... ................................... ................................... Dr. Athanasios Triantafyllou Dr. Apostolos Mintzelas Dr. Antonios Papapantoleon Lecturer, University of Essex KPMG Greece Assistant Professor, NTUA Athens, June 2019 ................................... Stavros Vatikiotis MSc Mathematical Modeling in Modern Technologies and Financial Engineering, NTUA Copyright © Stavros Vatikiotis All rights reserved. Copy, save and distribution of the present work, complete or by parts, is prohibited for any commercial use. Printing, save and distribution for no profit use,