Documentation of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Measures of Small Farmers in Central Visayas, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of CRM Learning Destinations in the Philippines 2Nd

Directory of CRMLearningDestinations in the Philippines by League of Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP), Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, World Wide Fund for Nature- Philippines (WWF-Philippines), and Conservation International (CI). 2ND EDITION 2009 Printed in Cebu City, Philippines Citation: LMP, FISH Project, WWF-Philippines, and CI-Philippines. 2009. Directory of CRM Learning Destinations in the Philippines. 2nd Edition. League of Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP), Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, World Wide Fund for Nature-Philippines (WWF-Philippines), and Conservation International-Philippines (CI-Philippines). Cebu City, Philippines. This publication was made possible through support provided by the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project of the Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions of USAID Contract Nos. AID-492-C-00-96-00028- 00 and AID-492-C-00-03-00022-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID. This publication may be reproduced or quoted in other publications as long as proper reference is made to the source. Partner coordination: Howard Cafugauan, Marlito Guidote, Blady Mancenido, and Rebecca Pestaño-Smith Contributions: Camiguin Coastal Resource Management Project: Evelyn Deguit Conservation International-Philippines: Pacifico Beldia II, Annabelle Cruz-Trinidad and Sheila Vergara Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation: Atty. Rose-Liza Eisma-Osorio FISH Project: Atty. Leoderico Avila, Jr., Kristina Dalusung, Joey Gatus, Aniceta Gulayan, Moh. -

PHL-OCHA-Bohol Barangay 19Oct2013

Philippines: Bohol Sag Cordoba Sagasa Lapu-Lapu City Banacon San Fernando Naga City Jagoliao Mahanay Mahanay Gaus Alumar Nasingin Pandanon Pinamgo Maomawan Handumon Busalian Jandayan Norte Suba Jandayan Sur Malingin Western Cabul-an San Francisco Butan Eastern Cabul-an Bagacay Tulang Poblacion Poblacion Puerto San Pedro Tugas Taytay Burgos Tanghaligue San Jose Lipata Saguise Salog Santo Niño Poblacion Carlos P. Garcia San Isidro San Jose San Pedro Tugas Saguise Nueva Estrella Tuboran Lapinig Corte Baud Cangmundo Balintawak Santo Niño San Carlos Poblacion Tilmobo Carcar Bonbonon Cuaming Bien Unido Mandawa Campao Occidental Rizal San Jose San Agustin Nueva Esperanza Campamanog San Vicente Tugnao Santo Rosario Villa Milagrosa Canmangao Bayog Buyog Sikatuna Jetafe Liberty Cruz Campao Oriental Zamora Pres. Carlos P. Garcia Kabangkalan Pangpang San Roque Aguining Asinan Cantores La Victoria Cabasakan Tagum Norte Bogo Poblacion Hunan Cambus-Oc Poblacion Bago Sweetland Basiao Bonotbonot Talibon San Vicente Tagum Sur Achila Mocaboc Island Hambongan Rufo Hill Bantuan Guinobatan Humayhumay Santo Niño Bato Magsaysay Mabuhay Cabigohan Sentinila Lawis Kinan-Oan Popoo Cambuhat Overland Lusong Bugang Cangawa Cantuba Soom Tapon Tapal Hinlayagan Ilaud Baud Camambugan Poblacion Bagongbanwa Baluarte Santo Tomas La Union San Isidro Ondol Fatima Dait Bugaong Fatima Lubang Catoogan Katarungan San Isidro Lapacan Sur Nueva Granada Hinlayagan Ilaya Union Merryland Cantomugcad Puting Bato Tuboran Casate Tipolo Saa Dait Sur Cawag Trinidad Banlasan Manuel M. Roxas -

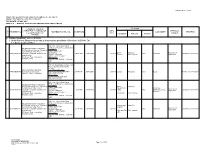

A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned Pursuant to the Pertinent Provisions of Section 4 of EO No

ANNEX B Page 1 of 105 MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU REGIONAL OFFICE NO. VII MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF MAY, 2017 ANNEX B - MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) TENEMENT HOLDER/ LOCATION line PRESIDENT/ CHAIRMAN OF AREA PREVIOUS TENEMENT NO. ADDRESS/FAX/TEL. NO. DATE FILED COMMODITY REMARKS no. THE BOARD/CONTACT (has.) Barangay/s Mun./City Province HOLDER PERSON A. MINING TENEMENT APPLICATIONS 1. Under Process (Returned pursuant to the pertinent provisions of Section 4 of EO No. 79) 1.1. By the Regional Office 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. Paul Vincent Arcenas - President Tinaan, Naga, Cebu Contact Person: Atty. Elvira C. Contact Nos.: Bairan Naga City Apo Cement 1 APSA000011VII Oquendo - Corporate Secretary and 06/03/1991 10/02/2009 240.0116 Cebu Limestone Returned on 03/31/2016 (032)273-3300 to 09 Tananas San Fernando Corporation Legal Director FAX No. - (032)273-9372 Mr. Gery L. Rota - Operations Manila Office: Manager (Cebu) (632)849-3754; FAX No. - (632)849- 3580 6th Floor, Quad Alpha Centrum, 125 Pioneer St., Mandaluyong City Tel. Nos. Atlas Consolidated Mining & Cebu Office (Mine Site): 2 APSA000013VII Development Corporation (032) 325-2215/(032) 467-1408 06/14/1991 01/11/2008 287.6172 Camp-8 Minglanilla Cebu Basalt Returned on 03/31/2016 Alfredo C. Ramos - President FAX - (032) 467-1288 Manila Office: (02)635-2387/(02)635-4495 FAX - (02) 635-4495 25th Floor, Petron Mega Plaza 358 Sen. Gil Puyat Ave., Makati City Apo Land and Quarry Corporation Cebu Office: Mr. -

(Ituugrrs:S: Uf F4r J4ilippiurs: ~Eftil J1lmilt

Chan Robles Virtual Law Library H. No. 4815 ~JIU&lic ilft4~ JlriliJlpitm (ituugrrs:s: uf f4r J4ilippiurs: ~eftil J1Lmilt gJf ilUtbrnf4I1I.ilU\lt~SS W:4idl ~gul/lt '~SSiilU • Begun and held in Metro Manila, on Monday, the twenty-seventh day of July, two thousand nine. [REPUBLIC ACT No. 98 '( 9 ] AN ACT SEPARATING THE ANDILI NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - TUBORAN ANNEX IN BARANGAY TUBORAN,MUNICIPALITYOFMAWAB,PROVINCEOF COMPOSTELA VALLEY FROM THE MAIN ANDILI NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL, CONVERTING IT INTO AN INDEPENDENT NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL TO BE KNOWN AS TUBORAN NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled' SECTION 1. Separation and Conversion into a National High School. - The Andili National High School - Tuboran Annex in Barangay Tuboran, Municipality ofMawab, Province of Compostela Valley is hereby separated from the MainAndili National High School and converted into an independent national high school to be known as Tuboran National High School. SEC. 2. Transfer ofAssets and Liabilities. - All pe,rsonnel, assets, liabilities and records of the Andili National High School Tuboran Annex are hereby transferred to and absorbed by the Tuboran National High School. www.chanrobles.com Chan Robles Virtual Law Library 2 SEC. 3. Appropriations. - The Secretary of Education shall immediately include in the Department's program the operationalizatiQn ofthe Tuboran National High School, the initial funding of which shall.be charged against the current year's appropriationsof.the Andili National High School- Tuboran Annex. Thereafter, the amount necessary for the continued operation ofthe school shall be included in the annual General Appropriations Act. -

DM-No.-098-S.-2020.Pdf

Bt*nhtic st tle Sllilf$$i$e$ &slisrtr$s$t sf Sbu*stisn itegi*n tr'Il * {.'}-XT-{{A{, \:lS.{\'-{$ scHosls sruIsl&f{ oF B0}N0r- Office of the Schools Division $uperintendent February 24,20?,* D31)"ISIOIT I?IEM{}NAIS SUM $*.q-f8' s. 2o2o fB*Til BIIILDI1YG ACTIIIT?T {ffi*atal l{*altb S*nagcment Frotoeel-GAl} Cosnpoaent} TO " : fiilIIHP F8O.TECT OWETR SDI'CATIT}H FBOGRAS SI'FER\NSOII IIT EI}IDAIIrCE ASD VAI,I'ES EtrT}CILTIOS DAXS rOCAt pEBS(}IT ffiE$TCAL $;rETCEB DrllIsxs$ 03' StlHoL Rs{tr$"rE8tD omsAfiss so$xsEr,olt,s IS? Coor*iastsr-In*ba*g* ISf$e $choal trEst-f 1, e, S FS*$e, ELEHEII"*5I? and $ECOI$B.*.RY B*HSOL &I}HUTIS?XA?GRS 1. ?his Olfice announces the conduct of the Team-Building Aetivities in the pilot implements.tion of Mental Heatth Ma:ragement Protoeol {MHMP} ?CI20 on the follouring schedules: Mareh 5-7. ?S20 {Thurxd*y-$aturday}- Ubay I I}istrict Participants lv€arch 1S-21, 2*20 {Thursday-satr"uday} IJbay Distriet ? Farticipants March26*?8, 202C {?hursda-v-Saturday} Ubay 3 District Pa.rticipants Venue: BPS?EA Br:ildizrg, Tagbilaran Citj' 2. Particip*nis to this three-day Team-Brlilding activities &re the following: Vakres and Guida:rce Education Program Suprviscr Pmject Orruner Division *f Bahol Register+d Guidance Caunseior* {R0Cs}-Faci[ilatsrs ' PSDSslActing PSDSs in th* districts Eleme*tar-y and Secondary Schcol Administrators in the t}ree districts andomly $ele*ted Elemente.4r arrd $eccndary $choal Teachers as Pilct Implementers of tlre Prograra. -

![Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9882/solid-waste-management-sector-project-financed-by-adbs-technical-assistance-special-fund-tasf-other-sources-3729882.webp)

Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 45146 December 2014 Republic of the Philippines: Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- other sources]) Prepared by SEURECA and PHILKOEI International, Inc., in association with Lahmeyer IDP Consult For the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHI Final Report December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHHI SR10a Del Carmen SR12: Poverty and Social SRs to RRP from 1 to 9 SPAR Dimensions & Resettlement and IP Frameworks SR1: SR10b Janiuay SPA External Assistance to PART I: Poverty, Social Philippines Development and Gender SR2: Summary of SR10c La Trinidad PART II: Involuntary Resettlement Description of Subprojects SPAR and IPs SR3: Project Implementation SR10d Malay/ Boracay SR13 Institutional Development Final and Management Structure SPAR and Private Sector Participation Report SR4: Implementation R11a Del Carmen IEE SR14 Workshops and Field Reports Schedule and REA SR5: Capacity Development SR11b Janiuay IEEE and Plan REA SR6: Financial Management SR11c La Trinidad IEE Assessment and REAE SR7: Procurement Capacity SR11d Malay/ Boracay PAM Assessment IEE and REA SR8: Consultation and Participation Plan RRP SR9: Poverty and Social Dimensions December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................5 A. -

ANNEXES Volum

Annexes ANNEXES Volum e 3 Part I Supporting Tables Table Title Page I-A.1 Detailed Physiographic Description by Land System and by City/M unicipality, Province of Bohol ............................................. I-1 A.2 Soil Type Distribution by Land Topography/Relief per City/M unicipality, Province of Bohol .............................................. I-6 A.3 Soil Attributes: Soils Depth and Description, Soil Texture and Reaction, and Soil Fertility Status by City/M unicipality, Province of Bohol ............................................................................ I-9 A.4 Detailed Inventory of the NIPAS Areas in the Province of Bohol ............................................................................................ I-11 A.5 Bat Species in the Province of Bohol (As of M ay 2005) .............. I-13 A.6 List of W ildlife Species per M unicipality/City, Province of Bohol I-14 A.7 M ajor M ineral, M etallic and Non-M etallic Deposits of Bohol, M ay 2005 ............................................................................ I-26 A.8a Non-M etallic M ineral Deposits of Bohol, M ay 2005 .................... I-27 A.8b Ore Reserves in the Province of Bohol, M ay 2005 ...................... I-27 A.9 Landslides/Subsidence/Slope Failure Incidences in Bohol (As of M ay 2005) ............................................................................. I-28 A.10 Flood Prone Areas in Bohol (As of M ay 2005) .............................. I-29 A.11 Total Population and Growth Rate, Num ber of Households and Average HH Size and Population Density, Province of Bohol; M ay 2000 Census ............................................................................ I-30 A.12 Projected Population by Age Group, Province of Bohol; CY 2000 – 2020 ................................................................................ I-32 A.13 Ten (10) Leading Causes of M orbidity, Num ber and Rate Per 100,000 Population in 2004 Com pared to the Past 5-Years Average (1999-2003), Province of Bohol .................................... -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR uFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized ReportNo. 7948 PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized PHILIPPINES RURAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT (CREDIT 790-PH) JUNE 30, 1989 Public Disclosure Authorized Adra-hure Operations Division CouintryDepartment II Public Disclosure Authorized Asia Regional Office This document has a restricted distribution and mat be used by recipients only in the performance of their official luties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorizstion. CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS Currency unit - Philippines Peso (O) P 1 - US$0.135 US$1 - 1 7.40 WEIGHTSAND MEASURES 1 ha - 2.47 acres 1 km - 0.62 miles 1 sq km - 0.386 sq mile 1 m - 3.28 ft 1 sq m = 10.76 sq ft 1 cu m - 35.31 cu ft 1 M cu m 3 810.7 ac ft 1 mm 00.039 in 1 kg - 2.2 lb 1 cavan = 50 kg 20 cavans = 1 m ton ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank AID - Agency for International Development BAE - Bureau of Agricultural Extension BBR - Bureau of Barangay Roads BHS - Barangay health Station BPI - Bureau of Plant Industry BPW - Bureau of Public Works CCC - Cabinet Coordinating Committee on Rural Development CP - Cooperative Program CPO - Central Project Organization DAR - Department of Agrarian Reforms DLGCD - Department of Local Government and Community Development DOH - Department of Health DPH - Departmont of Public Highways DPWTC - Department of Public Works, Transportation and Communications FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization FSDC - Farm Systems Development Corporation ISA - Irrigation -

Coastal Environmental and Fisheries Profile of Danajon Bank, Bohol, Philippines

CCOOAASSTTAALL EENNVVIIRROONNMMEENNTTAALL AANNDD FFIISSHHEERRIIEESS PPRROOFFIILLEE OOFF DDAANNAAJJOONN BBAANNKK,, BBOOHHOOLL,, PPHHIILLIIPPPPIINNEESS PATRICK CHRISTIE NYGIEL B. ARMADA ALAN T. WHITE ANECITA M. GULAYAN HOMER HERMES Y. DE DIOS COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL AND FISHERIES PROFILE OF DANAJON BANK, BOHOL, PHILIPPINES PATRICK CHRISTIE NYGIEL B. ARMADA ALAN T. WHITE ANECITA M. GULAYAN HOMER HERMES Y. DE DIOS COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL AND FISHERIES PROFILE OF DANAJON BANK, BOHOL, PHILIPPINES Patrick Christie Nygiel B. Armada Alan T. White Aniceta M. Gulayan Homer Hermes Y. de Dios 2006 Cebu City, Philippines Citation Christie, P., N.B. Armada, A.T. White, A.M. Gulayan and H.H.Y. de Dios. 2006. Coastal environmental and fisheries profile of Danajon Bank, Bohol, Philippines. Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, Cebu City, Philippines. 63 p. This publication was made possible through support provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions of Contract No. 492-C-00-03-00022-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID. This publication may be reproduced or quoted in other publications as long as proper reference is made to the source. FISH Document No.: 23-FISH/2006 II COASTAL ENVIRONMENTAL & FISHERIES PROFILE OF DANAJON BANK, BOHOL, PHILIPPINES TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS IV Ecological and biological significance and status 24 TABLES & FIGURES V Summary 26 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VII FOREWORD VIII -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 5

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BOHOL 1,255,128 ALBURQUERQUE 9,921 Bahi 787 Basacdacu 759 Cantiguib 555 Dangay 798 East Poblacion 1,829 Ponong 1,121 San Agustin 526 Santa Filomena 911 Tagbuane 888 Toril 706 West Poblacion 1,041 ALICIA 22,285 Cabatang 675 Cagongcagong 423 Cambaol 1,087 Cayacay 1,713 Del Monte 806 Katipunan 2,230 La Hacienda 3,710 Mahayag 687 Napo 1,255 Pagahat 586 Poblacion (Calingganay) 4,064 Progreso 1,019 Putlongcam 1,578 Sudlon (Omhor) 648 Untaga 1,804 ANDA 16,909 Almaria 392 Bacong 2,289 Badiang 1,277 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Buenasuerte 398 Candabong 2,297 Casica 406 Katipunan 503 Linawan 987 Lundag 1,029 Poblacion 1,295 Santa Cruz 1,123 Suba 1,125 Talisay 1,048 Tanod 487 Tawid 825 Virgen 1,428 ANTEQUERA 14,481 Angilan 1,012 Bantolinao 1,226 Bicahan 783 Bitaugan 591 Bungahan 744 Canlaas 736 Cansibuan 512 Can-omay 721 Celing 671 Danao 453 Danicop 576 Mag-aso 434 Poblacion 1,332 Quinapon-an 278 Santo Rosario 475 Tabuan 584 Tagubaas 386 Tupas 935 Ubojan 529 Viga 614 Villa Aurora (Canoc-oc) 889 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bohol Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and -

Congressional District 2 List of Grade V Teachers for English Proficiency Test 6 11

Republic of the Philippines Department of Education Region VII, Central Visayas DIVISION OF BOHOL CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 2 LIST OF GRADE V TEACHERS FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TEST ROOM 1 (A.M.)- San Roque NHS, Alburquerque No. Name District 1 Abarre MariaImaG. TugasES,Getafe 2 Abad JesseC. CPGCES Theresa Ubay1CES 3 Abapo > 4 Abapo Welenda VillaMilagrosaES,CPG 5 Abella AvelineD. GetafeCES Abregana Jonalyn SanMiguelES,Dagohoy 6 , 7 Aclao Lucile SaguiseES,CPG 8 Alcazar AntonietteV. Talibon 1 9 Amba CrisdtinaA. Talibon 1 Amorin UrsulaT. Buenavista 10 , 11 Ampo Ruel VillaTeresitaES,Ubay3 12 Anana VeronicaE. Buenavista 13 Anto QueenieE. Buenavista 14 Anzano WilmaP. HandumonES,Getafe 15 Aparece CitoA. Buenavista Aparece DoreenC. Buenavista 16 , 17 Aparri Veronica DagohoyCES 18 Aranzado UnaM. GarciaES,SanMiguel 19 Artiaga ServeniaF. Talibon 1 Aurestila Margie DiisES,Trinidad 20 i Autentico Juliet LaVictoriaES,Trinidad 21 / 22 Auxtero ElvanaT. CabatuanES,Danao Avenido Ma.Lolete TrinidadCES 23 i 24 Ayento Donato0. SanCarlosES,Danao 25 Baay BernadethC. CorazonES,SanMiguel 26 Bacante NelmaS. JagoliaoES,Getafe 27 Bagot MescilM. Buenavista 28 Baja Melisa SinandiganES,Ubay2 29 Balabat CindyC. Talibon 1 Baliientos MariaNilLBuenavista 30 i (Note for the EXAMINEES) brings pencils (lead No. 2 bring snacks clean sheet of paper & sharpener must know the school ID his/her respective school CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT 2 LIST OF GRADE V TEACHERS FOR ENGLISH PROFICIENCY TEST ROOM2(A.M.)-SanRoqueNHS, Alburquerque 1 3alonga MeriamE. t Talibon 1 2 3amba ChristopherS. t Ubay1CES 3 Bantono Anjo i Talibon 1 4 Batiller LynnE. / 3uenavista 5 3autiata Prisco / Talibon 1 6 3autista JaniceC. / 3uenavista 7 Belga AnalynT. i CangmundoES,Getafe 8 Belida MarianitoV. / SanVicenteES,CPG 9 Bendanillo Analie Pag-asaES,Ubay3 10 Bentulan Helen TipoloEs,Ubay2 11 3ernales Marissa BenliwES,Ubay2 12 Besira Esterlita i Talibon 1 13 Betaizar CecileGraceE. -

LIST of BFAR 7 LIVELIHOOD PROJECTS IMPLEMENTED for CY 2012 BOHOL Name of Project Barangay/Municipality/Province Name of Association No

LIST OF BFAR 7 LIVELIHOOD PROJECTS IMPLEMENTED FOR CY 2012 BOHOL Name of Project Barangay/Municipality/Province Name of Association No. of Project Cost Year/Funding Source Beneficiaries 2012 establishment A. Aquaculture SEAWEED GROW-OUT Tintinan, Ubay, Bohol Tintinan Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Tres Reyes, Ubay, Bohol Tres Reyes Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Humay-humay, Ubay, Bohol Humay-humay Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Catmonan, Calape, Bohol Catmonan Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Bogo, Carlos P. Garcia, Bohol Bogo Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Campamanog, Carlos P. Garcia, Bohol Campamanog Fishermen's Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Hingotanan East, Bien Unido, Bohol Hingotanan East Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Guindacpan, Tubigon, Bohol Guindacpan Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Dipatlog, Maribojoc, Bohol Maribojoc Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED GROW-OUT Lagtangon, Maribojoc, Bohol Lagtangon Seaweed Growers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Busalian, Talibon, Bohol Busalian Agriculture Fishery Dev't. Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Kahayag, Lawis, Calape, Bohol Kahayag Fisherfolk Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Campao Occ., Calape, Bohol Campao Occ. Seaweed Farmers Association 15 37,500.00 SEAWEED SEEDLINGS DISTRIBUTION Tintinan, Ubay, Bohol Tintinan Fisherfolk