Effect of Adherence to the World Health Organization Surgical Safety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contri Butors

CONTRI BUTORS A Bhagwati Department of Medicine President, Urological Society of India Honorary Physician LLRM Medical College (2008-2009) Rhatia Hospital, Wockhardt Hospitals and Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India President, Indian Medical Association Motiben Dalvi Hospitals (2007-2008) S-nt. Adil Farooq Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Council Member, World Medical Aditya Prakash Misra Association(WMA) A Kader Sahib Senior Consultant, Physician Consultant Cardiologist Ajinkya Borhade Jessa Ram Hospital, Hospital and Ayesha Hospital Apollo New Delhi, India PG, DNB, Medicine Trichy, Tamil Nadu, India Sundaram Arulrhaj Hospitals AG Unnikrishnan Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu, India A Muruganathan Endocrinologist and CEO Adjunct Professor Head of Patient Care AK Agarwal Thmil Nadu Dr MGR Medical University Research and Education Professor and Head Tirupur, Thmil Nadu, India Chellaram Diabetes Institute School of Medical Science and Research Pune, Maharashtra, India A R Vijayaku mar (SMS & R) Rtd. HOD and Professor Medicine Agam Vora Sharda Hospital and University Greater Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India Coimbatore Medical College and Asst. Hon. & In Charge - Dept of Chest & PSG Institute of Medical Science and TB, Dr. RN Cooper Muni. Gen. Hospital, Research, Coimbatore Mumbai, Maharashtra, India Akashdeep Singh Consulting Physician Professor Associate Professor GKNM Hospital, Coimbatore Department of Chest & TB Department of Pulmonary Medicine Member, Research Committee KiSomaiya Dayanand Medical College and Hospital Association of Physicians of India Medical -

Chronic Arsenicosis in India

Seminar: Chronic Arsenicosis in India EEpidemiologypidemiology andand preventionprevention ofof chronicchronic arsenicosis:arsenicosis: AnAn IndianIndian pperspectiveerspective PPramitramit GGhosh,hosh, CChinmoyihinmoyi RRoyoy2, NNilayilay KKantianti DDasas1, SSujitujit RRanjananjan SSenguptaengupta3 Departments of Community Medicine and 1Dermatology, Medical College, Kolkata-700 073, 2State Water Investigation Directorate, Govt. of West Bengal, 3Dept. of Dermatology, IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata-700 020, India AAddressddress fforor ccorrespondence:orrespondence: Nilay Kanti Das, Devitala Road, Majerpara, Ishapore-743 144, India. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Arsenicosis is a global problem but the recent data reveals that Asian countries, India and Bangladesh in particular, are the worst sufferers. In India, the state of West Bengal bears the major brunt of the problem, with almost 12 districts presently in the grip of this deadly disease. Recent reports suggest that other states in the Ganga/Brahmaputra plains are also showing alarming levels of arsenic in ground water. In West Bengal, the majority of registered cases are from the district of Nadia, and the maximum number of deaths due to arsenicosis is from the district of South 24 Paraganas. The reason behind the problem in India is thought to be mainly geogenic, though there are instances of reported anthropogenic contamination of arsenic from industrial sources. The reason for leaching of arsenic in ground water is attributed to various factors, including excessive withdrawal of ground water for the purpose of irrigation, use of bio-control agents and phosphate fertilizers. It remains a mystery why all those who are exposed to arsenic-contaminated water do not develop the full-blown disease. Various host factors, such as nutritional status, socioeconomic status, and genetic polymorphism, are thought to make a person vulnerable to the disease. -

Laparoscopic Adrenalectomy: a Single Center Experience

Original Article Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: A single center experience Suresh Kumar, Moley K Bera, Mukesh K Vijay, Arindam Dutt, Punit Tiwari, Anup K Kundu Department of Urology, Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGMER) and Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital (SSKM), Kolkata - 700 020, India Address for correspondence: Dr. Suresh Kumar, 601 Doctors PG Hostel, 242 AJC Bose Road, IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata - 700 020, West Bengal, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract performed via the transperitoneal or retroperitoneal route- the former via the lateral or anterior approach and the latter AIMS: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of laparoscopic via the posterior approach. Robot-assisted laparoscopic adrenalectomy in benign adrenal disorders. METHODS adrenalectomy may also be performed if facilities are AND MATERIAL: Since July 2007, twenty patients available. Each technique has its own advantages and have undergone laparoscopic adrenalectomy for various benign adrenal disorders at our institution. Every patient disadvantages. It is now an established fact that different underwent contrast enhanced CT-abdomen. Serum advantages of the laparoscopic approach include less corticosteroid levels were conducted in all, and urinary morbidity, better cosmesis, reduction in wound infection, metanephrines, normetanephrines and VMA levels minimal need for analgesia, decreased hospital stay and early were performed in suspected pheochromocytoma. All return to work.[2-4] We report our experience of laparoscopic the patients underwent laparoscopic adrenalectomy via adrenalectomy using the transperitoneal approach in 20 the transperitoneal approach. : The patients RESULTS patients with different adrenal pathology. This prospective were in the age range of 18-57 years, eleven males study was conducted in our Urology Department to evaluate and nine females, seven right, eleven left, two bilateral. -

2020 Lahiri Et Al Hallucinatory Palinopsia and Paroxysmal Oscillopsia

cortex 124 (2020) 188e192 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cortex Hallucinatory palinopsia and paroxysmal oscillopsia as initial manifestations of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: A case study Durjoy Lahiri a, Souvik Dubey a, Biman K. Ray a and Alfredo Ardila b,c,* a Bangur Institute of Neurosciences, IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata, India b Sechenov University, Moscow, Russia c Albizu University, Miami, FL, USA article info abstract Article history: Background: Heidenhain variant of Cruetzfeldt Jacob Disease is a rare phenotype of the Received 4 August 2019 disease. Early and isolated visual symptoms characterize this particular variant of CJD. Reviewed 7 October 2019 Other typical symptoms pertaining to muti-axial neurological involvement usually appear Revised 9 October 2019 in following weeks to months. Commonly reported visual difficulties in Heidenhain variant Accepted 14 November 2019 are visual dimness, restricted field of vision, agnosias and spatial difficulties. We report Action editor Peter Garrard here a case of Heidenhain variant that presented with very unusual symptoms of pal- Published online 13 December 2019 inopsia and oscillopsia. Case presentation: A 62-year-old male patient presented with symptoms of prolonged af- Keywords: terimages following removal of visual stimulus. It was later on accompanied by intermit- Creutzfeldt Jacob disease tent sense of unstable visual scene. He underwent surgery in suspicion of cataratcogenous Heidenhain variant vision loss but with no improvement in symptoms. Additionally he developed symptoms of Oscillopsia cerebellar ataxia, cognitive decline and multifocal myoclonus in subsequent weeks. On the Palinopsia basis of suggestive MRI findings in brain, typical EEG changes and a positive result of 14-3-3 protein in CSF, he was eventually diagnosed as sCJD. -

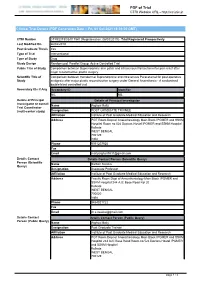

CTRI Trial Data

PDF of Trial CTRI Website URL - http://ctri.nic.in Clinical Trial Details (PDF Generation Date :- Fri, 01 Oct 2021 18:39:00 GMT) CTRI Number CTRI/2019/03/017947 [Registered on: 06/03/2019] - Trial Registered Prospectively Last Modified On 26/02/2019 Post Graduate Thesis Yes Type of Trial Interventional Type of Study Drug Study Design Randomized, Parallel Group, Active Controlled Trial Public Title of Study Comparison between Buprenorphine skin patch and intravenous Paracetamol for pain relief after major reconstructive plastic surgery Scientific Title of Comparison between transdermal Buprenorphine and intravenous Paracetamol for post-operative Study analgesia after major plastic reconstructive surgery under General Anaesthesia - A randomised double blind controlled trial. Secondary IDs if Any Secondary ID Identifier NIL NIL Details of Principal Details of Principal Investigator Investigator or overall Name Arghya Maity Trial Coordinator (multi-center study) Designation POST GRADUATE TRAINEE Affiliation Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research Address PGT Room Dept of Anaesthesiology Main Block IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Room no 524 Doctors Hostel IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Kolkata WEST BENGAL 700129 India Phone 9051207925 Fax Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Scientific Query) Person (Scientific Name Sarbari Swaika Query) Designation Associate Professor Affiliation Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research Address Faculty Room Dept of Anaesthesiology Main Block IPGMER -

Medicine Update 2016) Brothers

Progress in Medicine 2016 (Medicine Update 2016) Brothers Jaypee For Private Circulation Only Progress in Medicine and Medicine Update 2016 The publication of this book has been made possible by Unconditional educational grant from: USV Limited The scientific committee is also thankful for the unconditionalBrothers grants from: India Medtronic Abbott Healthcare Mankind Pharma MICRO Labs Cipla Limited Dr Reddy’s Lab Eris Lifesciences, Intas Pharma, Macleods Pharma, Abbott Vasc., Zydus Cadila, IPCA, Sanofi Aventis, Novo Nordisk, and Emcure Pharma Volume 26–2016 ISBN: 978-93-5250-199-1 © All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by Xerox, microfilm or any other means without written permission from the editors and publisher. The editors have checked the validity of information provided in the book, and to the best of their knowledge, it is as per the standards accepted at the time of publication. The views and opinions of the authors do not represent the policies of The AssociationJaypee of Physicians of India or the editors. Published by Gurpreet S Wander, KK Pareek Design, Typeset, Print and Distributed by Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers (P) Ltd Progress in Medicine 2016 (Medicine Update 2016) 1st VOLUME Chief Editors KK Pareek MD Senior Consultant in MedicineBrothers and Director SN Pareek Memorial Hospital and Research Center Kota, Rajasthan, India Gurpreet S Wander MD DM Professor and Head Department of Cardiology Hero DMC Heart Institute Dayanand Medical College and Hospital Ludhiana, Punjab, India Foreword Siddharth -

Clinical Trial Details (PDF Generation Date :- Thu, 30 Sep 2021 00:31:36 GMT)

PDF of Trial CTRI Website URL - http://ctri.nic.in Clinical Trial Details (PDF Generation Date :- Thu, 30 Sep 2021 00:31:36 GMT) CTRI Number CTRI/2013/12/004264 [Registered on: 31/12/2013] - Trial Registered Retrospectively Last Modified On 10/12/2013 Post Graduate Thesis Yes Type of Trial Interventional Type of Study Drug Study Design Randomized, Parallel Group Trial Public Title of Study Oral glucocorticoids vs. intravenous glucocorticoids in managing thyroid associated orbitopathy Scientific Title of Monthly pulse methylprednisolone vs. oral prednisolone in treatment of thyroid ophthalmopathy: An Study open label randomized controlled trial Secondary IDs if Any Secondary ID Identifier NIL NIL Details of Principal Details of Principal Investigator Investigator or overall Name Dr Subhankar Chowdhury Trial Coordinator (multi-center study) Designation Professor and Head of the Department Affiliation IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Address Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism Room 8, 4th floor, Ronald Ross Building IPGMER and SSKM Hospital 244 AJC Bose Road Calcutta Kolkata WEST BENGAL 700020 India Phone 9831076501 Fax Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Scientific Query) Person (Scientific Name Dr Ajitesh Roy Query) Designation Post-doctoral trainee Affiliation IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Address Room 8, 4th floor, Ronald Ross Building Department of Endocrinology Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education & Research (IPGMER) Kolkata-700020 Kolkata WEST BENGAL 700020 India Phone 9433135863 Fax Email -

Dr.Anirban Dey* Dr.Santanu Sen Roy INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Volume - 9 | Issue - 12 | December - 2020 | PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8179 | DOI : 10.36106/ijsr INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH EVALUATION OF ORAL HYGIENE KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND BEHAVIOUR AMONG LOCAL AUTO-RICKSHAW DRIVERS IN SODEPUR, KOLKATA, INDIA. Dental Science B.D.S., Guru Nanak Institute of Dental Sciences and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, Dr.Anirban Dey* India.*Corresponding Author Dr.Santanu Sen Reader, Department of Public Health Dentistry, Guru Nanak Institute of Dental Sciences Roy and Research, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Dr.Debarshi Jana Young Scientist, IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. ABSTRACT The aim of the short study is to evaluate self-reported oral health knowledge attitudes and behaviour among local auto-rickshaw drivers inSodepur, Kolkata, India. Materials and Method: A cross-sectional study was conducted on 50 auto-rickshaw drivers and was carried out with the help of 10 questions. Age, gender and level of education data was recorded. Statistical analysis was performed with the help of Epi Info ™ 7.2.2.2 EPI INFO is a trademark of the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using the Chi-Square test (x2). Results: The (mean ± S.D.) age of the respondents was (38.62±14.03) with range 19 – 70 years and the median age was 35.5 years. Most of the participants (56.0%) were with age between 20 - 39 years. About 76.0% of the participants was with the level of education up to middle standard (up to 9th standard). The variation of scores of knowledge and attitude, also showed highly signicant with level of education and behaviour being non-signicant. -

Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research

Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research Kolkata An exclusive Guide by Institute of Post Graduate Medical Education and Research Admission 2021: NEET PG Dates (Out), Eligibility, Selection Process, Application Form Updated on Mar 10, 2021 Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research (IPGMER), also known as PG Hospital (Presidency General Hospital) or SSKM Hospital is a government hospital for the state of West Bengal and is a national research institute. is a national research institute located in Kolkata, West Bengal. The institute was established in the year 1957 and is currently affiliated to the West Bengal University of Health Sciences, Kolkata. Latest Update February 23, 2021: NEET PG 2021 registrations have started. Last date for the registration is March 15. Table of Contents 1. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Admission 2021: Highlights 2. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Admission 2021: Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 20-Sep-2021. MBBS, BPT, BSc (Nursing), GNM 3. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital MSc Admission 2021 4. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Admission 2021: MD, MS 5. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Paramedical Admission 2021 6. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Admission 2021: DM, MCh 7. IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Application Process 2021 IPGMER and SSKM Hospital Admission 2021: Highlights IPGMER offers several undergraduate, postgraduate and postdoctoral programs including super specialty programs in various disciplines of Medical Sciences. Candidates will have to apply for NEET-UG examination conducted by CBSE to take admission in MBBS Candidates applying for other UG courses have to take the form online from the official website of IPGMER Candidates applying for PG courses have to apply online through NEET-PG conducted by NBE Disclaimer: This PDF is auto-generated based on the information available on Shiksha as on 20-Sep-2021. -

CTRI Trial Data

PDF of Trial CTRI Website URL - http://ctri.nic.in Clinical Trial Details (PDF Generation Date :- Sun, 26 Sep 2021 04:25:26 GMT) CTRI Number CTRI/2019/05/019468 [Registered on: 31/05/2019] - Trial Registered Prospectively Last Modified On 30/05/2019 Post Graduate Thesis Yes Type of Trial Interventional Type of Study Drug Surgical/Anesthesia Study Design Randomized, Parallel Group Trial Public Title of Study Comparison of regional cerebral oxygen saturation variations between "sevoflurane" and "propofol" anaesthesia in gynaecological laparoscopic surgery Scientific Title of Comparison of regional cerebral oxygen saturation variations between Sevoflurane and Propofol Study anaesthesia in Gynaecological laparoscopic surgery Secondary IDs if Any Secondary ID Identifier NIL NIL Details of Principal Details of Principal Investigator Investigator or overall Name Atul Aman Trial Coordinator (multi-center study) Designation JR Affiliation ipgmer and sskm hospital Address Department of Anaesthesiology, 3rd floor, 244, ipgmer, harish mukherjee road, bhowanipore, kolkata Kolkata WEST BENGAL 700020 India Phone 09088955257 Fax Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Scientific Query) Person (Scientific Name Atul Aman Query) Designation JR Affiliation ipgmer & sskm hospital Address Department of Anaesthesiology, 3rd floor, 244, ipgmer harish mukherjee road, bhowanipore, kolkata Kolkata WEST BENGAL 700020 India Phone 09088955257 Fax Email [email protected] Details Contact Details Contact Person (Public Query) Person -

A Case of True Hermaphrodite Presenting As Cyclical Hematuria

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2013): 6.14 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 A Case of True Hermaphrodite Presenting as Cyclical Hematuria Soumendra Mishra1, Suchandra Ray2 1PGT, Department of Pathology, IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, The West Bengal University of Health Sciences, Kolkata-700020. India 2Associate Professor, Department of Pathology, IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata-700020, India Abstract: True hermaphrodite (also known as ovotesticular disorder of sexual development or ovotesticular-DSD), is one of the rare varieties of disorder of sexual development. It is characterized by histologically confirmed both ovarian and testicular tissue in one individual. Here we report the case of a16-year-old phenotypic male with 46, XX genotype(true hermaphrodite) presenting with cyclical hematuria and histologically diagnosed as ovotestis. Keywords: True hermaphrodite, ovotesticular DSD 1. Introduction 3cmx2cmx1cm. The right sided gonad sent separately measured 3cmx3cmx2cm with the attached fallopian tube Ovotesticular disorder of sex development (DSD) is a rare measuring 4cm in length. On cut section the right side gonad disease [1]. Most common presenting feature in these cases was partly solid and partly cystic. is genital ambiguity [2]. However, the phenotype may vary from normal female to normal male in appearance. Here we are describing a case of ovotesticular DSD, who presented with a complaint of cyclical hematuria. 2. Case Report Asixteen-year-old male patient presented at the endocrinology out-patient department of our institute with complaint of cyclical hematuria for 4-5days duration for one and a half months. Tanner staging of the patient was B5-P4- A1. -

Dr. Niraj Kumar Singh Dr. Ayan Ghosh INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Volume - 10 | Issue - 03 | March - 2021 | PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8179 | DOI : 10.36106/ijsr INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH A STUDY ON KNOWLEDGE ATTITUDE AND PRACTICE REGARDING ANIMAL BITE AMONG GENERAL AND SLUM POPULATION IN KOLKATA Medicine Dr. Niraj Kumar DNB (Post MBBS) 3rd Year, Social and Preventive Medicine, College of Medicine & Singh JNM Hospital, Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal. Assist Professor, Dept. of Community Medicine, College of Medicine & JNM Hospital, Dr. Ayan Ghosh Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal. Dr. Debrashi Jana* IPGMER and SSKM Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal.*Corresponding Author ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION: India is the second largest contributor to Rabies mortality in the world. According to a recent report of World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 55,000 human deaths are reported every year worldwide due to rabies, with an overwhelming majority of 32,000 cases reported in Asia of which 20,000 occur in India. AIMS: The general awareness about the rabies in general population, awareness of people about anti rabies vaccines and health services utilization. MATERIAL AND METHOD: The study was an observational, questionnaire-based study. For the purpose of this thesis, a descriptive co relational analytical survey was used, in which a qualitative approach was undertaken to determine the answers of mentioned research questions. The study was slum to the general people. The expected duration of the study was approximately six months between 1st January 2019 to 30st Dec 2019. RESULT AND DISCUSSION: We found that 77(51.3%) patients answered that on being bitten from an infected animal, both people and animals can get rabies, 46(30.7%) patients answered that on several sorts of contact with an infected animal (e.g.