Toxic Masculinity and the Generative Father in an Age of Narcissism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inside an Enigma

CAT-TALES IINSIDE AN EENIGMA CAT-TALES IINSIDE AN EENIGMA By Chris Dee COPYRIGHT © 2013 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION INSIDE AN ENIGMA Pre-dawn Gotham. The Batmobile raced across 58th Street while inside the man at the wheel considered the autopilot. The burn from last night’s fiery takedown of the Cráneos Sangrientos was sending fiery ripples down the sides of his fingers on his left hand. Beneath the gauntlet, the flesh across the outside of the palm remembered where the flames had licked down to the inner wrist, heating the gauntlet into a weapon that punished him as much as the biker on the other end of his fist. Still, a few days’ pain wasn’t much to pay compared to what was gained. The fall of the Cráneos would send a message. While the biker gang stuck with stealing motorcycles for their principle income with a sporadic sideline in crack cocaine, they were a GPD concern. One truckload of automatic weapons coming up from Atlanta promoted them from a secondary 12th Precinct nuisance to the first item of business on Batman’s Thursday Night hit list. “Autopilot engage. Home,” he graveled, releasing the wheel and ripping off the glove. Parts of the bandage came with it, and Bruce’s eyes nearly rolled from the new wave of pain as the cool dry air of the car hit the outraged flesh around the burn. He could see now that the bandage had been jostled during that last episode with the jumper, letting in air—the air inside the glove, air moist with his perspiration and warmed by his exertions. -

Spontaneous Generation

by Chris Dee CAT-TALES SSPONTANEOUS GGENERATION CAT-TALES SSPONTANEOUS GGENERATION By Chris Dee COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION SPONTANEOUS GENERATION Prologue: Ivy's Song Weakness. If there was one thing that made her physically ill, it was weakness. Nature was not weak. Nature was the ultimate power. What could man make that Nature could not destroy? Their fleshy bodies, their cities, their pitiful notions of achievement? What was a church compared to a forest? A painting compared to a mountain, a symphony next to a flower… Well, actually, she liked music. Even her plants liked music. Mozart in particular. And there was nothing in Nature to compare it to. The mathematical underpinnings of music were absolutely man-made, and it had to be said, it was… beautiful. A THOUGHT THAT MADE HER WANT TO SCREAM! Beautiful belonged to Nature. It belonged to Flowers. It was hers, and this filthy animal, masculine, homo sapien, civilized, plant-eating THING had made something that was wholly theirs, wholly unique, and wholly beautiful. JUST HAVING THE THOUGHT MADE HER WANT TO RIP HER HAIR OUT BY THE ROOT! It was so weak. Pamela’s little thoughts and feelings. As the living embodiment of the Goddess Lifeforce, Poison Ivy rebelled at the idea of hating any part of herself, but that, that… Pamela had become such a burden. People made something beautiful. It was disgusting. But now she had that thought in her head, and it was all because of that part of herself that, for lack of a better term, she called Pam. -

California TV 3X20.25 11-22.Indd

WEDNESDAY EVENING NOVEMBER 22, 2017 6 PM 6:30 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 6 PBS PBS NewsHour (N) Nature Nova Frontline "Poor Kids" Wicked World News Charlie Rose (N) 8 NBC News Wheel The Wall "Ruben and Sandy" Sat. Night "A Saturday Night Live Thanksgiving Special" KOMU 8 The Tonight Show (N) Late Night ` 9 CW Fam.Guy Fam.Guy iHeartRadio Music Festival Pt. 1 of 2 cont'd Nov 24 News Sein. Sein. Rules Rules Queens 13 CBS KRCG Live Ent. Tonight Survivor SEAL Team "The Exchange" Criminal Mind "Neon Terror" KRCG Live The Late Show (N) J.Corden ` 17 ABC ABC 17 News ABC 17 News Charlie Thanksgiving Modern Am.Wife Lights,Camera,C'mas! (N) ABC 17 News Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline ` 19 WGN Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops 22 FOX BBang BBang Empire "Noble Memory" Star ABC 17 News at 9 (N) Mike&M. Mike&M. 2 Broke 2 Broke 25 KNLJ Walk in Word The Great Awakening VFN TV Gospel Truth All the World St. Theatre MusicCount Awakening Awakening You & Me ` 10 A&E S. Wars S. Wars S. Wars S. Wars Storage S. Wars OzzyandJack'sDetour OzzyJack "Speed Demons" S. Wars S. Wars ` 10 BRAV <++ Maid in Manhattan ('02) Ralph Fiennes, Jennifer Lopez. <++ Maid in Manhattan ('02) Ralph Fiennes, Jennifer Lopez. <+++ Ocean's Eleven ('01,Cri) Brad Pitt, George Clooney. ` 11 SPIKE Friends Friends Friends Friends Shannara Chronic "Wildrun" Shannara Chronic "Blood" <++ X-Men: The Last Stand ('06) Patrick Stewart. -

BATMAN: a HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale

BATMAN: A HERO UNMASKED Narrative Analysis of a Superhero Tale BY KELLY A. BERG NELLIS Dr. William Deering, Chairman Dr. Leslie Midkiff-DeBauche Dr. Mark Tolstedt A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin August 1995 FORMC Report of Thesis Proposal Review Colleen A. Berg Nellis The Advisory Committee has reviewed the thesis proposal of the above named student. It is the committee's recommendation: X A) That the proposal be approved and that the thesis be completed as proposed, subject to the following understandings: B) That the proposal be resubmitted when the following deficiencies have been incorporated into a revision: Advisory Committee: Date: .::!°®E: \ ~jjj_s ~~~~------Advisor ~-.... ~·,i._,__,.\...,,_ .,;,,,,,/-~-v ok. ABSTRACT Comics are an integral aspect of America's development and culture. The comics have chronicled historical milestones, determined fashion and shaped the way society viewed events and issues. They also offered entertainment and escape. The comics were particularly effective in providing heroes for Americans of all ages. One of those heroes -- or more accurately, superheroes -- is the Batman. A crime-fighting, masked avenger, the Batman was one of few comic characters that survived more than a half-century of changes in the country. Unlike his counterpart and rival -- Superman -- the Batman's popularity has been attributed to his embodiment of human qualities. Thus, as a hero, the Batman says something about the culture for which he is an ideal. The character's longevity and the alterations he endured offer a glimpse into the society that invoked the transformations. -

Catwoman (White Queen)

KNI_05_p01 CS6.indd 1 10/09/2020 10:41 IN THIS ISSUE YOUR PIECE Meet your white queen – Gotham City’s 3 ultimate femme fatale Selina Kyle, better known as Catwoman. PROFILE From the slums of Gotham City’s East 4 End, Catwoman has become one of the world’s most famous thieves. GOTHAM GUIDE A examination of Gotham’s East End, a 10 grim area of crime and poverty – and the home of Selina Kyle. RANK & FILE Why Catwoman is the white queen and 12 how some of her moves are refl ected in those of the powerful chess piece. RULES & MOVES An essential guide to the white queen 15 and some specifi c gambits using the piece. Editor: Alan Cowsill Thanks to: Art Editor: Gary Gilbert Writers: Devin K. Grayson, Ed Brubaker, Frank Writer: James Hill Miller, Jeph Loeb, Will Pfeifer, Judd Winick, Consultant: Richard Jackson Darwyn Cooke, Andersen Grabrych. Figurine Sculptor: Imagika Sculpting Pencillers: Jim Balent, Michael Avon Oeming, Studio Ltd David Mazzucchelli, Cameron Stewart, Jim Lee, Pete Woods, Guillem March, Darwyn US CUSTOMER SERVICES Cooke, Brad rader, Rick Burchett. Call: +1 800 261 6898 Inkers: John Stanisci, Mike Manley, Scott Email: [email protected] Williams, Mike Allred, Rick Burchett, Cameron Stewart, Alavaro Lopez. UK CUSTOMER SERVICES Call: +44 (0) 191 490 6421 Email: [email protected] Batman created by Bob Kane with Bill Finger Copyright © 2020 DC Comics. CATWOMAN and all related characters and elements © and TM DC Comics. (s20) EAGL26789 Collectable Figurines. Not designed or intended for play by children. Do not dispose of fi gurine in the domestic waste. -

Abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz

MAIN LOGO This version of the logo should be used whenever possible on all print and digital materials. MAIN LOGO REVERSED MAIN LOGO CENTERED The logo should be reversed to white whenever it’s This logo should be used sparingly and only when placed on a dark or photographic background. spacing absolutely requires a centered format. SEPERATED LOGO ELEMENTS TAGLINE LOGOTYPE The logo elements alone should not be considered logos This logotype should be used whenever the tagline but brand assets, and should be used sparingly in is present. The tagline should never appear as independent contexts. regular typeset. SAFE AREA On all versions of the logo, a minimum clear space the size of two C’s from ‘Community’ is required on all sides. 88 / 20 / 100 / 10 75 /40 / 60 / 53 #008444 #426D61 PANTONE 348 PANTONE 7484 5 / 4 / 7 / 0 50 / 45 / 50 / 60 #EEECE7 #45443F PANTONE 7527 PANTONE WARM GREY 11 COLOR PALETTE These are the only colors that should be used when the main brand of CFEC is present. No other colors should be added or swapped in. INCORRECT APPLICATIONS THIS IS AN INCORRECTLY PLACED HEADLINE. Never stretch or distort the logo. Never put other elements too close to the logo. Never add a dropshodow or any effects. Never make the logo more than one color. INDIANA Never replace or remove any of the wording in the logo. Never change the orientation of the ginkgo leaf. Never place a non-reversed logo on a dark or photographic background. SUB BRANDS The sub brands for CFEC should appear in their full form whenever possible and should never vary in color. -

Batman and Robin As Evolving Cutural Icons Elizabeth C

St. Catherine University SOPHIA 2014 Sr. Seraphim Gibbons Undergraduate Sr. Seraphim Gibbons Undergraduate Symposium Research Symposium The Dynamic Duo Then and Now: Batman and Robin as Evolving Cutural Icons Elizabeth C. Wambheim St. Catherine University Follow this and additional works at: https://sophia.stkate.edu/undergraduate_research_symposium Wambheim, Elizabeth C., "The Dynamic Duo Then and Now: Batman and Robin as Evolving Cutural Icons" (2014). Sr. Seraphim Gibbons Undergraduate Symposium. 2. https://sophia.stkate.edu/undergraduate_research_symposium/2014/Humanities/2 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at SOPHIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sr. Seraphim Gibbons Undergraduate Symposium by an authorized administrator of SOPHIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DYNAMIC DUO THEN AND NOW: BATMAN AND ROBIN AS EVOLVING CULTURAL ICONS by Elizabeth C. Wambheim A Senior Project in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Honors Project ST. CATHERINE UNIVERSITY April 1, 2014 2 With many thanks to Patricia Montalbano (project advisor), Rachel Neiwart Emily West and Sharon Doherty for their continuous and invaluable interest, assistance, and patience with the project. 3 Introduction When presented with the simple silhouette of a stylized bat inside a yellow oval, people the world over are able to recognize this emblem and, at the very least, name its wearer. Even as the logo is altered with time, the yellow backdrop traded for a grey one, the awareness persists. Yet even as people recognize Batman’s logo, one person’s impression of the superhero does not always align with another’s: a cheerful, law-abiding Batman who orders orange juice instead of alcohol at bars is Batman as he appeared in the 1960s, and a brooding hero wreathed in darkness and prone to conflicted inner monologues is the Batman of the 1980s. -

Batman and the Superhero Fairytale: Deconstructing a Revisionist Crisis

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2013 Batman and the superhero fairytale: deconstructing a revisionist crisis Travis John Landhuis University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2013 Travis John Landhuis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Landhuis, Travis John, "Batman and the superhero fairytale: deconstructing a revisionist crisis" (2013). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 34. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/34 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by TRAVIS JOHN LANDHUIS 2013 All Rights Reserved BATMAN AND THE SUPERHERO FAIRYTALE: DECONSTRUCTING A REVISIONIST CRISIS An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Travis John Landhuis University of Northern Iowa December 2013 ABSTRACT Contemporary superhero comics carry the burden of navigating historical iterations and reiterations of canonical figures—Batman, Superman, Green Lantern et al.—producing a tension unique to a genre that thrives on the reconstruction of previously established narratives. This tension results in the complication of authorial and interpretive negotiation of basic principles of narrative and structure as readers and producers must seek to construct satisfactory identities for these icons. Similarly, the post-modern experimentation of Robert Coover—in Briar Rose and Stepmother—argues that we must no longer view contemporary fairytales as separate (cohesive) entities that may exist apart from their source narratives. -

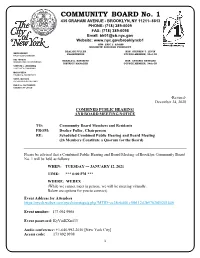

COMMUNITY BOARD No. 1

COMMUNITY BOARD No. 1 435 GRAHAM AVENUE - BROOKLYN, NY 11211- 8813 PHONE: (718) 389-0009 FAX: (718) 389-0098 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nyc.gov/brooklyncb1 HON. ERIC L. ADAMS BROOKLYN BOROUGH PRESIDENT DEALICE FULLER HON. STEPHEN T. LEVIN SIMON WEISER CHAIRPERSON COUNCILMEMBER, 33rd CD FIRST VICE-CHAIRMAN DEL TEAGUE GERALD A. ESPOSITO HON. ANTONIO REYNOSO SECOND VICE-CHAIRPERSON DISTRICT MANAGER COUNCILMEMBER, 34th CD STEPHEN J. WEIDBERG THIRD VICE-CHAIRMAN MARIA VIERA FINANCIAL SECRETARY SONIA IGLESIAS RECORDING SECRETARY PHILIP A. CAPONEGRO MEMBER-AT-LARGE -Revised- December 24, 2020 COMBINED PUBLIC HEARING AND BOARD MEETING NOTICE TO: Community Board Members and Residents FROM: Dealice Fuller, Chairperson RE: Scheduled Combined Public Hearing and Board Meeting (26 Members Constitute a Quorum for the Board) Please be advised that a Combined Public Hearing and Board Meeting of Brooklyn Community Board No. 1 will be held as follows: WHEN: TUESDAY --- JANUARY 12, 2021 TIME: *** 6:00 PM *** WHERE: WEBEX (While we cannot meet in person, we will be meeting virtually. Below are options for you to connect) Event Address for Attendees https://nyccb.webex.com/nyccb/onstage/g.php?MTID=ec38c6e801cf0b112d2b97620852414d6 Event number: 173 092 9908 Event password: KyVutKXn433 Audio conference: +1-646-992-2010 [New York City] Access code: 173 092 9908 1 Note to All Board Members: You must sign into the meeting using the Email address that you have provided to the office, otherwise you will not be able access the meeting. PUBLIC HEARING 1. ROLL CALL 2. PRESENTATION: Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs - Information on the City’s Critical Programs and Resources Under COVID – by Mr. -

Awarding Quilts of Valor

IN SPORTS: Sumter wrestling rallies for 37-36 home dual-meet win over Socastee B1 THE CLARENDON SUN New Summerton business serves up homemade goodies A6 THURSDAY, JANUARY 26, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Awarding Quilts of Valor BEN DICKMANN / SPECIAL TO THE SUMTER ITEM Kristan Ann Ware, who grew up in Sumter, is a Miami Dolphins cheerleader co-captain. Pure heart and a humble spirit Sumter woman shares faith while cheering on Dolphins BY KONSTANTIN VENGEROWSKY [email protected] Kristan Ann Ware has kept her hum- ble spirit and strong Christian faith while achieving success and fame as a Miami Dolphins cheerleader co-captain. The Wichita Falls, Texas, native, who JIM HILLEY / THE SUMTER ITEM was raised in Sumter and attended high Harvey Mayhill watches as Linda Heyward wraps a Quilt of Valor around her father, Roy Weatherbee, of Sumter, during an Ed- school at Thomas Sumter Academy, wards High School reunion lunch on Wednesday at Golden Corral in Sumter. said she always knew she wanted to do something that was out of her comfort zone. 4 World War II Navy vets receive honor “I love spreading joy and wanted to get out there in the world and make a BY JIM HILLEY erans they do not know, but Hey- difference,” she said. “It just so hap- [email protected] ward sewed the one given to her pened to be as an NFL cheerleader.” father, he said. Ware has used her fame in a unique Four World War II Navy veter- Since the founding of Quilts of way to spread the message of Christ. -

Gotham Episode Guide Episodes 001–100

Gotham Episode Guide Episodes 001–100 Last episode aired Thursday April 25, 2019 www.fox.com c c 2019 www.tv.com c 2019 www.fox.com The summaries and recaps of all the Gotham episodes were downloaded from http://www.tv.com and http://www. fox.com and processed through a perl program to transform them in a LATEX file, for pretty printing. So, do not blame me for errors in the text ! This booklet was LATEXed on May 2, 2019 by footstep11 with create_eps_guide v0.61 Contents Season 1 1 1 Pilot ...............................................3 2 Selina Kyle . .7 3 The Balloonman . 11 4 Arkham . 15 5 Viper............................................... 19 6 Spirit of the Goat . 23 7 Penguin’s Umbrella . 27 8 The Mask . 31 9 Harvey Dent . 35 10 LoveCraft . 39 11 Rogues’ Gallery . 43 12 What the Little Bird Told Him . 47 13 Welcome Back, Jim Gordon . 51 14 The Fearsome Dr. Crane . 55 15 The Scarecrow . 59 16 The Blind Fortune Teller . 63 17 Red Hood . 67 18 Everyone Has a Cobblepot . 71 19 Beasts of Prey . 75 20 Under the Knife . 79 21 The Anvil or the Hammer . 83 22 All Happy Families Are Alike . 87 Season 2 91 1 Rise of the Villains: Damned If You Do... 93 2 Rise of the Villains: Knock, Knock . 97 3 Rise of the Villains: The Last Laugh . 101 4 Rise of the Villains: Strike Force . 105 5 Rise of the Villains: Scarification . 109 6 Rise of the Villains: By Fire . 113 7 Rise of the Villains: Mommy’s Little Monster . -

“Truth Written in Hell-Fire”: William James and the Destruction of Gotham

“TRUTH WRITTEN IN HELL-FIRE”: WILLIAM JAMES AND THE DESTRUCTION OF GOTHAM JUSTIN ROGERS-COOPER This essay reads Joaquin Miller’s 1886 novel The Destruction of Gotham for how it resonates with strands of “radical pragmatism” in William James’s thought. It argues for the ways James’s philosophy might explain political and social movements beyond liberalism, including general strikes and class revolt. The essay emphasizes the many political possibilities immanent in pluralistic pragmatism, from the “revolutionary suicide” we see in the novel’s class insurgency to the ways such collective violence also registers as an incipient mode of American fascism, or what the essay calls “bad pragmatism.” WILLIAM JAMES STUDIES • VOLUME 13 • NUMBER 2 • FALL 2017 • PP. 240-281 “TRUTH WRITTEN IN HELL-FIRE” 241 ewis Menand writes that “one of the lessons the Civil War had taught” William James and the metaphysical club was that “the moral justification for our actions comes from the tolerance we have shown to other ways Lof being in the world,” adding that the “alternative was force. Pragmatism was designed to make it harder for people to be driven to violence by their beliefs.”1 Menand thus sees pragmatism as “the intellectual triumph of unionism”: the creation of a marketplace of ideas in which everyone participates equally and without coercion.2 Menand’s interpretation of the political valences of pragmatism is more or less commonplace; it recalls, for instance, Charlene Haddock Seigfried’s similar summation that “the guiding principle ought to be to satisfy at all times as many demands as possible.”3 For Menand, the possibilities of pragmatism are circumscribed by the personal politics of the members of metaphysical club.