Twice Heard, Hardly Seen: the Self-Translator's (In) Visibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DERRINSTOWN STUD Tel: +353 (0)1 6286228 in 2018 [email protected] Awtaad 2018 Fee: €15,000 (1St Jan

FRIDAY, 26TH JANUARY 2018 GALE FORCE EBN TEN EUROPEAN BLOODSTOCK NEWS FOR MORE INFORMATION: TEL: +44 (0) 1638 666512 • FAX: +44 (0) 1638 666516 • [email protected] • WWW.BLOODSTOCKNEWS.EU RACING REVIEW | OBS SALES TALK | STAKES RESULTS | STAKES FIELDS TODAY’S HEADLINES STALLION NEWS FIRST FOALS FOR BELARDO AND ROCK The first foals by the dual Gr.1 winners Belardo and Fascinating Rock have arrived and both are fillies. The Belardo filly was born at Ferdlant Stud in Newmarket on Tuesday, and is out of the five-year-old Acclamation mare Mayberain, she was described as “a cracking stamp of a foal, very correct and with good bone” by Ferdlant Stud’s Lianne Barrett. Mayberain was lightly raced, but hails from the superb family of Rain Flower, dam of both the Gr.1 Oaks heroine Dancing Rain (Danehill Dancer; dam of the Gr.1-placed juvenile Magic Lily) Fascinating Rock’s first-born daughter with her well-related and Mayberain’s Listed-winning second dam Sumora (Danehill), dam, Serenity Dove (Harbour Watch), pictured at Ringfort who produced the Gr.1 Moyglare Stud Stakes heroine Maybe Stud. (Galileo), herself dam of Gr.1 Racing Post Trophy winner Saxon Warrior and the Gr.3 Silver Flash Stakes winner and Gr.1 Prix Marcel Boussac runner-up Promise To Be True (Galileo). At three, he finished second to the Champion Solow (Singspiel) Belardo (Lope De Vega) was an outstanding juvenile when in the Gr.1 Queen Elizabeth II Stakes, before adding another Gr.1 trained by Roger Varian, winning his maiden and following up in win to his tally in the Lockinge Stakes as an older horse. -

2000 Foot Problems at Harris Seminar, Nov

CALIFORNIA THOROUGHBRED Adios Bill Silic—Mar. 79 sold at Keeneland, Oct—13 Adkins, Kirk—Nov. 20p; demonstrated new techniques for Anson, Ron & Susie—owners of Peach Flat, Jul. 39 2000 foot problems at Harris seminar, Nov. 21 Answer Do S.—won by Full Moon Madness, Jul. 40 JANUARY TO DECEMBER Admirably—Feb. 102p Answer Do—Jul. 20; 3rd place finisher in 1990 Cal Cup Admise (Fr)—Sep. 18 Sprint, Oct. 24; won 1992 Cal Cup Sprint, Oct. 24 Advance Deposit Wagering—May. 1 Anthony, John Ed—Jul. 9 ABBREVIATIONS Affectionately—Apr. 19 Antonsen, Per—co-owner stakes winner Rebuild Trust, Jun. AHC—American Horse Council Affirmed H.—won by Tiznow, Aug. 26 30; trainer at Harris Farms, Dec. 22; cmt. on early training ARCI—Association of Racing Commissioners International Affirmed—Jan. 19; Laffit Pincay Jr.’s favorite horse & winner of Tiznow, Dec. 22 BC—Breeders’ Cup of ’79 Hollywood Gold Cup, Jan. 12; Jan. 5p; Aug. 17 Apollo—sire of Harvest Girl, Nov. 58 CHRB—California Horse Racing Board African Horse Sickness—Jan. 118 Applebite Farms—stand stallion Distinctive Cat, Sep. 23; cmt—comment Africander—Jan. 34 Oct. 58; Dec. 12 CTBA—California Thoroughbred Breeders Association Aga Khan—bred Khaled in England, Apr. 19 Apreciada—Nov. 28; Nov. 36 CTBF—California Thoroughbred Breeders Foundation Agitate—influential broodmare sire for California, Nov. 14 Aptitude—Jul. 13 CTT—California Thorooughbred Trainers Agnew, Dan—Apr. 9 Arabian Light—1999 Del Mar sale graduate, Jul. 18p; Jul. 20; edit—editorial Ahearn, James—co-author Efficacy of Breeders Award with won Graduation S., Sep. 31; Sep. -

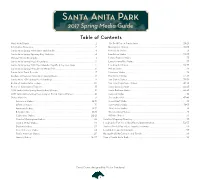

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

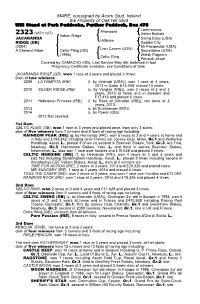

MARE, Consigned by Acorn Stud, Ireland the Property of Oak Hill Stud

MARE, consigned by Acorn Stud, Ireland the Property of Oak Hill Stud Will Stand at Park Paddocks, Further Paddock, Box 476 Lorenzaccio Ahonoora 2323 (WITH VAT) Helen Nichols Indian Ridge Swing Easy (USA) JACARANDA Hillbrow RIDGE (GB) Golden City (2004) Mr Prospector (USA) Lion Cavern (USA) A Chesnut Mare Celtic Fling (GB) Secrettame (USA) (1996) Welsh Pageant Celtic Ring Pencuik Jewel Covered by CAMACHO (GB). Last Service May 4th; believed in foal. Pregnancy Certificate available, see Conditions of Sale. JACARANDA RIDGE (GB), won 1 race at 3 years and placed 3 times; Dam of two winners: 2009 LA PAMPITA (IRE) (f. by Intikhab (USA)), won 1 race at 4 years, 2013 in Qatar, £15,058, placed 13 times. 2010 SILVER RIDGE (IRE) (c. by Verglas (IRE)), won 3 races at 2 and 3 years, 2013 at home and in Sweden and £17,416 and placed 6 times. 2011 Hebridean Princess (IRE) (f. by Rock of Gibraltar (IRE)), ran twice at 2 years, 2013. 2013 (c. by Bushranger (IRE)). 2014 (c. by Power (GB)). 2012 Not covered. 1st Dam CELTIC FLING (GB), won 1 race at 3 years and placed once, from only 3 starts; dam of five winners from 7 runners and 8 foals of racing age including- RAINBOW PEAK (IRE) (g. by Hernando (FR)), won 5 races at 3 and 4 years at home and in Italy and £199,842 including Gran Premio del Jockey Club, Milan, Gr.1 and Wolferton Handicap, Ascot, L., placed 4 times viz second in Strensall Stakes, York, Gr.3, Arc Trial, Newbury, Gr.3, Hambleton Stakes, York, L. -

The Japan Cup in Association with LONGINES

The 40th Running of The Japan Cup in association with LONGINES Press Information THE JAPAN RACING ASSOCIATION November 2020 SCHEDULE Date Event Nov. 29 (Sun.) ... JAPAN CUP (12th Race, 3:40 p.m) Last year’s Winner: Suave Richard (JPN, by Heart’s Cry) *1Information is as of November 15, 2020 *2Race record of Japanese horses includes both JRA the regional and races overseas, while record of JRA trainers and jockeys includes JRA flat races only unless otherwise indicated. 1 Japan Autumn International 40th JAPAN CUP Date of Race: Sunday, November 29, 2020 Racecourse: Tokyo Racecourse Distance: 2,400 meters (about 12 furlongs), turf, left-handed Age: 3-year-olds & up Weight: 4-year-olds & up: 57 kilograms (about 126 lbs.) 3-year-olds: 55 kilograms (about 121 lbs.) Allowance: Fillies and Mares: 2 kilograms Southern Hemisphere Horses born in 2017: 2 kilograms Safety Factor: 18 runners Total Value: JPY 648,000,000 (about US$ 5,892,000) (Note: US$1 = ¥110) Prize Money Participation Incentive Money Winner JPY 300,000,000 (US$ 2,727,273) 6th JPY 24,000,000 (US$ 218,182) 2nd JPY 120,000,000 (US$ 1,090,909) 7th JPY 21,000,000 (US$ 190,909) 3rd JPY 075,000,000 (US$ 0,681,818) 8th JPY 18,000,000 (US$ 163,636) 4th JPY 045,000,000 (US$ 0,409,091) 9th JPY 09,000,000 (US$ 081,818) 5th JPY 030,000,000 (US$ 0,272,727) 10th JPY 06,000,000 (US$ 054,545) Bonus System: Japan Cup For the winners of races below in 2020 Bonus 2020 H. -

Top Beyer Speed Figures • 1993-2018

TOP BEYER SPEED FIGURES • 1993-2018 2-year-olds, 1993 2-year-olds, 1996 Beyer Beyer No. Horse Track Dist Date No. Horse Track Dist Date 106 VALIANT NATURE HOL 8.5 12/19/1993 108 THISNEARLYWASMINE SA 6 10/23/1996 105 BROCCO HOL 8.5 12/19/1993 107 KELLY KIP SAR 6 07/26/1996 105 POLAR EXPEDITION AP 6 08/14/1993 106 IN EXCESSIVE BULL SA 6 10/23/1996 103 HOLY BULL BEL 7 09/18/1993 104 HOLZMEISTER HAW 8.5 11/17/1996 102 DEHERE BEL 7 09/18/1993 104 KELLY KIP BEL 5 06/21/1996 101 HOLY BULL MTH 5.5 08/14/1993 103 IN C C’S HONOR LRL 6 12/21/1996 100 FLYING SENSATION HOL 8.5 12/19/1993 102 DIXIE FLAG (F) AQU 6 11/24/1996 100 SARDULA (F) DMR 7 09/04/1993 101 CAPTAIN BODGIT LRL 9 11/02/1996 99 BLUMIN AFFAIR HOL 8.5 12/19/1993 101 GOLD CASE FG 6 12/30/1996 99 INDIVIDUAL STYLE HOL 7 11/26/1993 101 IN EXCESSIVE BULL HOL 7 11/10/1996 99 YOU AND I AQU 7 10/20/1993 101 IN EXCESSIVE BULL SA 6 10/05/1996 Champion 2-year-old male Dehere had one of the highest Beyer Speed 101 MUD ROUTE HOL 6.5 12/15/1996 Figures of the season, but Valiant Nature earned the highest when beating 101 ORDWAY BEL 8.5 10/05/1996 Breeders’ Cup Juvenile winner Brocco in the Hollywood Futurity. -

Media Guideu T

ANITA PA A R T K N A S A Media GuideU T 5 U 1 M 0 2 N • American Pharoah & Victor Espinoza 2014 FrontRunner Stakes 2 2015 Santa anita autumn media Guide GENERAL INFORMATION/PUBLICITY DEPT. PHONE NUMBERS ......................................... 2 SANTA ANITA AUTUMN STAKES HISTORIES ..............................................................16-37 INFORMATION RESOURCES ............................................................................................ 3 BREEDERS’ CUP AT SANTA ANITA STAKES HISTORIES .............................................38-43 RIDING LEGEND DELAHOUSSAYE WILL AGAIN BE HONORED ........................................... 4 SANTA ANITA AUTUMN INACTIVE STAKES ................................................................44-49 SANTA ANITA AUTUMN DATES, ATTENDANCE & HANDLE .............................................. 10 LOS ANGELES TURF CLUB, INC. BOARD OF DIRECTORS & ADMINISTRATION ............50-51 SANTA ANITA AUTUMN OPENING DAY STATISTICS ........................................................ 10 CALIFORNIA HORSE RACING BOARD ............................................................................ 50 2014 SANTA ANITA AUTUMN FINAL STATISTICS/PARI-MUTUEL PAYOFFS ...................... 11 VISITORS GUIDE ........................................................................................................... 52 PREVIOUS SANTA ANITA AUTUMN MEET LEADERS ....................................................... 12 RESTAURANTS AND HOTELS NEAR SANTA ANITA ........................................................ -

![Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4480/papers-of-clare-boothe-luce-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-1694480.webp)

Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Clare Boothe Luce A Register of Her Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Nan Thompson Ernst with the assistance of Joseph K. Brooks, Paul Colton, Patricia Craig, Michael W. Giese, Patrick Holyfield, Lisa Madison, Margaret Martin, Brian McGuire, Scott McLemee, Susie H. Moody, John Monagle, Andrew M. Passett, Thelma Queen, Sara Schoo and Robert A. Vietrogoski Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003044 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of Clare Boothe Luce Span Dates: 1862-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1930-1987) ID No.: MSS30759 Creator: Luce, Clare Boothe, 1903-1987 Extent: 460,000 items; 796 containers plus 11 oversize, 1 classified, 1 top secret; 319 linear feet; 41 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Journalist, playwright, magazine editor, U.S. representative from Connecticut, and U.S. ambassador to Italy. Family papers, correspondence, literary files, congressional and ambassadorial files, speech files, scrapbooks, and other papers documenting Luce's personal and public life as a journalist, playwright, politician, member of Congress, ambassador, and government official. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Barrie, Michael--Correspondence. Baruch, Bernard M. -

Keeneland's Top Filly

Friday, Thoroughbred Daily News April 19, 2002 TDN For information, call (732) 747-8060. HEADLINE NEWS KING FOR A DAY MINARDI SET TO SHUTTLE Sir Michael Stoute was guarded in his optimism after Champion Minardi (Boundary--Yarn, by Mr. Prospec- King of Happiness (Spinning World) had booked his tor) will stand the Southern Hemishpere season at New place in the line-up for the G1 2000 Guineas May 4 Zealand’s Glenmorgan Farm for a fee of NZ$15,000. He with the trainer’s seventh success in the G3 Craven at entered stud this spring at Walmac Farm near Newmarket yesterday. “You had to be pleased with Lexington. A $1.65 that, as it was a nice, smooth performance,” said Keeneland September Stoute. “However, there will be a few tougher nuts to yearling purchase, crack on Guineas day. He loves this ground and he Minardi went on to cap- wouldn’t want it any softer than good as that would ture the G1 Heinz 57 count against him.” Della Francesca (Danzig) was sent Phoenix S. and the G1 to the front in the early stages, but as that colt was Middle Park S. and was passed by Silence and Rage (GB) (Green Desert), the named champion at two tempo quickened considerably. Kieren Fallon was able in both England and Ire- to stalk the pace astride King of Happiness before ask- land. “We are over the ing him to close on the outside inside the final three Minardi winning the Phoenix moon to have been able furlongs. The 220,000gns Houghton yearling struck the Courtesy: NZTM to secure Minardi for front with a quarter mile remaining and was pushed out New Zealand breeders,” said Brett Jenkins of Glenmor- a comfortable winner. -

Celtic Swing (Gb)

CELTIC SWING (GB) RAISE A NATIVE MR PROSPECTOR GOLD DIGGER DAMISTER ROMAN LINE CELTIC SWING BATUCADA WHISTLE A TUNE (GB) (1992) A BROWN TUDOR MELODY HORSE WELSH PAGEANT PICTURE LIGHT CELTIC RING (1984) PETINGO PENCUIK JEWEL FOTHERINGAY CELTIC SWING (GB), Champion 2yr old in Europe in 1994, Jt 4th top rated 3yr old in England in 1995, won 5 races at 2 and 3 years, £470,938 including Prix du Jockey Club, Chantilly, Gr.1, Racing Post Trophy, Doncaster, Gr.1 and Greenham Stakes, Newbury, Gr.3, placed second in 2000 Guineas, Newmarket, Gr.1; sire. 1st Dam CELTIC RING, won 2 races at 3 and 4 years and £11,629 and placed 3 times; dam of 4 winners including- CELTIC SWING (GB), see above. CELTIC FLING (GB) (1996 f. by Lion Cavern), won 1 race at 3 years; dam of- CELTIC HEROINE (IRE) (f. by Hernando (FR)), 4 races at 2 and 3 years and £62,163 including Sandringham Stakes, Ascot, L., placed second in Weatherbys EBF Valiant Stakes, Ascot, L. 2nd Dam PENCUIK JEWEL, ran twice on the flat at 2 and 3 years; dam of 4 winners including- RIFLE PENCUIK, won 18 races in Italy and £26,798. CELTIC RING, see above. 3rd Dam FOTHERINGAY, won 1 race at 3 years and placed 3 times, all her starts; dam of 5 winners including: CASTLE KEEP (c. by Kalamoun), won 10 races including Grand Prix Prince Rose, Ostend, Gr.1, Doonside Cup, Ayr, L., Land Of Burns Stakes, Ayr, L. and Clive Graham Stakes, Goodwood, L., placed fourth in Benson & Hedges Gold Cup, York, Gr.1 and Coronation Cup, Epsom, Gr.1; sire. -

John Voss Jen Currin Jagmeet Singh Alan Twigg

JAGMEET SINGH JOHN VOSS JEN CURRIN ALAN TWIGG His memoir of love Around the world in a Exploring LGBTQ+ Good-bye and and courage. 13 dugout canoe. 22-23 lives & loves. 34 thank you. 42 BCYOUR FREE GUIDE TO BOOKS & AUTHORS BOOKWORLD VOL. 33 • NO. 3 • Autumn 2019 BEAU DICK His war versus consumerism. 9 Photo by Boomer Jerritt Beau Dick, Alert Bay artist and renegade. #40010086 AGREEMENT INDIGENOUS SISTERS & MAIL A TRICKSTER RULE IN A NEW PLAY, KAMLOOPA. 5 PUBLICATION READ THE WILD. SAVE THE WILD. 9781459819986 $24.95 HC 9781459816855 $24.95 HC OrCa ´3DJHVÀOOHGZLWK SKRWRJUDSKV ´$VROLGDQG wILd LPSDVVLRQHGQDUUDWLYH DSSHDOLQJDGGLWLRQ ¶2UFD%LWHV·DQGIXUWKHU WRHQGDQJHUHG UHVHDUFKUHVRXUFHV VSHFLHVOLWHUDWXUHµ PDNHWKLVWLWOHRQH —Booklist IRUDOOOLEUDULHVµ —Booklist “i made this blanket for the survivors, and for the children who never came home; for the dispossessed, the displaced and the forgotten. i made this blanket so that i will never forget—so that we will never forget.” —Carey Newman, hc author and master carver 9781459819955 $39.95 2 BC BOOKWORLD • AUTUMN 2019 BC TOP “Axe, axe, foot, foot, repeat. What a way to live.” PEOPLE The first▼ ften the only woman on excur- sions, on the outskirts of a male SELLERS pack, Sharon Wood has long O been aware that her personal accomplishments are also on Angela Crocker ASCENT behalf of female climbers everywhere. Vicki McLeod Long before Sharon Wood became the & first North American woman to reach the Digital Legacy Plan: for many A Guide to the Personal and top of Everest in 1986—also becoming the Practical Elements of Your first woman to ever reach the summit by the Digital Life Before You Die difficult West Ridge, via a new route from (Self-Counsel $19.95) Tibet, without Sherpa support—Wood has been in the vanguard of North American Nevin J. -

2020 International List of Protected Names

INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (only available on IFHA Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 03/06/21 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne-Billancourt, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org The list of Protected Names includes the names of : Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally renowned, either as main stallions and broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or jump) From 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf Since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous following international races : South America : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil Asia : Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup Europe : Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion North America : Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf The main stallions and broodmares, registered on request of the International Stud Book Committee (ISBC). Updates made on the IFHA website The horses whose name has been protected on request of a Horseracing Authority. Updates made on the IFHA website * 2 03/06/2021 In 2020, the list of Protected