Jana Smith Elford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

183 Anti-Valentine's Day Songs (2015)

183 Anti-Valentine's Day Songs (2015) 4:24 Time Artist Album Theme Knowing Me Knowing You 4:02 Abba Gold Break up Lay All Your Love On Me 5:00 Abba Gold cautionary tale S.O.S. 3:23 Abba Gold heartbreak Winner Takes it All 4:55 Abba Gold Break up Someone Like You 4:45 Adele 21 Lost Love Turning Tables 4:08 Adele 21 broken heart Rolling in the Deep 3:54 Adlele 21 broken heart All Out Of Love 4:01 Air Supply Ulitimate Air Supply Lonely You Oughta Know 4:09 Alanis Morissette Jagged Little Pill broken heart Another heart calls 4:07 All American Rejects When the World Comes Down jerk Fallin' Apart 3:26 All American Rejects When the World Comes Down broken heart Gives You Hell 3:33 All American Rejects When the World Comes Down moving on Toxic Valentine 2:52 All Time Low Jennifer's Body broken heart I'm Outta Love 4:02 Anastacia Single giving up Complicated 4:05 Avril Lavigne Let Go heartbreak Good Lovin' Gone Bad 3:36 Bad Company Straight Shooter cautionary tale Able to Love (Sfaction Mix) 3:27 Benny Benassi & The Biz No Matter What You Do / Able to Love moving on Single Ladies (Put a Ring On It) 3:13 Beyonce I Am Sasha Fierce empowered The Best Thing I Never Had 4:14 Beyonce 4 moving on Love Burns 2:25 Black Rebel Motorcycle Club B.R.M.C. cautionary tale I'm Sorry, Baby But You Can't Stand In My Light Anymore 3:11 Bob Mould Life & Times moving on I Don't Wish You Were Dead Anymore 2:45 Bowling for Soup Sorry for Partyin' broken heart Love Drunk 3:47 Boys Like Girls Love Drunk cautionary tale Stronger 3:24 Britney Spears Opps!.. -

Favorite Artists in Today's Music Wrld

May 15, 2020 Created by (doja cat & lil uzi vert) (bruno mars & eminem) (taylor swift & rihanna) Dadaism On each of our pages, you will find a “guess the song” section. This was inspired by the Cut-Up technique, an aleatory literary technique where a written text is cut up word-by-word and then completely rearranged, resulting in a new text. This technique can be traced back to the Dadaists in the 1920s, a group of avant-garde artists located primarily in Europe. Since then, the Cut-Up technique has been used in a variety of other contexts. On our pages, we have taken a popular song from each artist, then used the Dadaist cut-up technique to scramble the lyrics and create a new text. We chose to do this to pay homage to and remind us of the avant-garde artists and the history of avant-garde zines. So, if you would like, take a shot at guessing the songs. The answers are found on the final page. We hope you enjoy our little game and, in the process, are reminded of how all zines began. The Next King of POp BrunoBruno MarsMars AMerican Smooth|King|Unique|Icon|Catchy singer/songwriter POPPOP | | SOUL SOUL | | FUNK FUNK | | R&B R&B REGGAEREGGAE | | ROCK ROCK | | HIP-HOP HIP-HOP Album #3 24K 11-time Magic (2016) had huge Grammy successes, Winner including tons of awards and nominations. 24K Magic: 2018 Grammy named one of AWARDS the best songs of the year by many including Won ALL 6 Billboard, won a Major Grammy for Record of the Guess that song Categories Year (2018) The face when and Cause for stares NOMINATED you I; That’s What I would stops the IN Way while The you LIke: topped whole world; Just I a; Billboard 100s, 2nd Album: 7th #1 single in Thing are; 1st Album: Unorthodox US, won three Just not you; Doo-Wops and Jukebox Grammys for Your and way a; Hooligans Best Song, Best Amazing you’re See amazing you’re; R&B when that smile. -

ARIA CATALOGUE ALBUMS CHART WEEK COMMENCING 24 MAY, 2021 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TW THIS WEEK LW LAST WEEK TI TIMES IN HP HIGH POSITION ARIA CATALOGUE ALBUMS CHART WEEK COMMENCING 24 MAY, 2021 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED CAT NO. 1 1 7 1 WHEN WE ALL FALL ASLEEP, WHERE DO WE GO? Billie Eilish <P>3 B002972702 2 2 80 1 DIAMONDS Elton John <P> 5768187 3 3 115 1 ÷ Ed Sheeran <D> 9029585903 4 5 182 3 SINGLES COLLECTION Maroon 5 4754556 5 4 301 1 RUMOURS Fleetwood Mac <P>13 8122796778 6 6 102 1 THIS ONE'S FOR YOU Luke Combs <P> 19075829282 7 7 527 2 CURTAIN CALL: THE HITS Eminem <P>12 9887893 8 8 238 1 1989 Taylor Swift <D> 3799890 9 12 30 6 BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY (THE ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK) Queen <P>2 6798870 10 11 188 1 DOO-WOPS & HOOLIGANS Bruno Mars <P>4 7567891215 11 10 42 1 HAMILTON - AN AMERICAN MUSICAL Original Broadway Cast 7567866843 12 9 395 1 THE VERY BEST INXS <D> 5335934 13 13 176 5 IRON MAN 2 AC/DC <P> 88697662142 14 14 102 3 DUA LIPA Dua Lipa <G> 9029555948 15 15 61 5 ? XXXTentacion <P> 1210673 16 23 78 5 HARRY STYLES Harry Styles <P> 88985436772 17 26 368 1 BON JOVI GREATEST HITS - THE ULTIMATE COLLECTION Bon Jovi <P>8 2752336 18 21 75 11 GREATEST HITS: GOD'S FAVORITE BAND Green Day 9362490917 19 25 263 1 TEENAGE DREAM: THE COMPLETE CONFECTION Katy Perry <P>6 0818536 20 22 55 4 BEERBONGS & BENTLEYS Post Malone <P>2 B002821802 21 47 451 1 GREATEST HITS Queen <P>15 2758364 22 19 20 19 LIVE IN BUENOS AIRES Coldplay 9029555399 23 16 75 4 THE GREATEST SHOWMAN Soundtrack <P>3 7567865927 24 18 86 7 AM Arctic Monkeys <P>2 3747478 25 -

Imposter Next Door: a Study on Authenticity in The

IMPOSTER NEXT DOOR: A STUDY ON AUTHENTICITY IN THE MODERN POP STAR by Chris Cantu HONORS THESIS Submitted to Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors College May 2020 Thesis Supervisor: Rachel Romero Second Reader: Amber Lupo IMPOSTER NEXT DOOR: A STUDY ON AUTHENTICITY IN THE MODERN POP STAR by Chris Cantu May 2020 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Chris Cantu, authoriZe duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Putting together this thesis has been something of a lifelong endeavor. In essence, it is the blueprint by which I intend to launch my career as a recording artist and songwriter. I could have never imagined combining my greatest passions – academia and pop culture – without the incredible guidance of Dr. Rachel Romero. The critical curiosity she has sparked within me, class after class, has completely changed the way I approach the world. Throughout my tenure at Texas State, Dr. Romero has been a gifted educator, wise mentor, and ultimately a genuine friend. I’d like to thank her for her unyielding support throughout this process, and her incredible impact on my life. -

Order Form Full

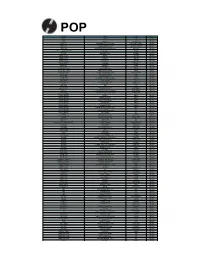

POP ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADELE 19 (180 GR) CBS RM133.00 ADELE 21 CBS RM116.00 ADELE 25 (180 GR) XL RECORDINGS RM138.00 AMOS, TORI ABNORMALLY ATTRACTED TO SIN UNIVERSAL REPUBLIC RM151.00 AMOS, TORI LITTLE EARTHQUAKES (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UNDER THE PINK (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UPSIDE DOWN: FM RADIO BROADCASTS BAD JOKER RM122.00 BENNETT, TONY & LADY GAGA CHEEK TO CHEEK POLYDOR RM127.00 BEYONCE BEYONCE COLUMBIA RM178.00 BEYONCE LEMONADE (180 GR) COLUMBIA RM159.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN BELIEVE DEF JAM RM112.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN JOURNALS DEF JAM RM140.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD DEF JAM RM112.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD 2.0 DEF JAM RM112.00 BILLIE JOE & NORAH FOREVERLY WARNER BROS RM124.00 BUGG, JAKE ON MY ONE ISLAND RM134.00 BUGG, JAKE SHANGRI-LA ISLAND RM134.00 CHARLI XCX SUCKER ATLANTIC RM117.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT FLYING HIGH (180 GR) GET HIP RM97.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT RIBBON OF GOLD (180 GR) GET HIP RM97.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT THE KIDS ARE THE SAME (180 GR) GET HIP/COLUMBIA RM110.00 COLLINS, PHIL ...BUT SERIOUSLY (180 GR) RHINO RM154.00 COLLINS, PHIL FACE VALUE (180 GR) RHINO RM124.00 COLLINS, PHIL NO JACKET REQUIRED (180 GR) RHINO RM124.00 CULTURE CLUB LIVE AT WEMBLEY - WORLD TOUR 2016 CLEOPATRA RM127.00 CYRUS, MILEY YOUNGER NOW RCA RM125.00 DARE, DOUGLAS AFORGER (CLEAR VINYL) ERASED TAPES RM142.00 DUFFY ROCKFERRY MERCURY RM112.00 EKKO, MIKKY TIME RCA RM103.00 FALL OUT BOY INFINITY ON HIGH (180 GR) ISLAND RM151.00 FURTADO, NELLY THE RIDE (180 GR) NELSTAR MUSIC RM134.00 GO-GO'S LET'S HAVE A PARTY: -

Department Regulation No

Department Regulation No. C-02-009 Offender Mail and Publications Revised 02 July 2019 REJECTION LIST Publications: A Witches Bible – The Complete Witches Handbook Airbrush Action – September/October 2010, March/April 2016 Airbrush Bible AL-HAGG Newsletter Volume 10 Issue 3 Al-Haq Allure - May 2008, December 2011, March 2017 Alternative Revolution – Issue #14 American Art Collector – June 2014 Issue #104, July 2014, #108 October 2014, #109 November 2014, February 2015 American Artist - Spring 2009, May 2010, November 2011, October 2012 American Curves – June 2006, July 2006, November 2006, January 2007, Eye Candy for Men – February 2007, May 2007, Duos Spring 2007, #34 – June 2007, Eye Candy – August 2007 – To Be Displayed Until October 16, 2007, October 2007, Presents Lingerie Magazine – November 2007– December 2007, February 2008, Eye Candy for Men – March 2008, May 2008, June 2008, July 2008, December 2008, Eye Candy for Men - January 2009, February 2009, Eye Candy for Men - May 2009, April 2010, Summer 2012, American Photo - September 2008, November/December 2008, January/February 2009, March/April 2009, May/June 2009, September 2009, May/June 2011 Amerikkkan Prisons on Trial – Guilty! – Number 11-1996 An Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons & True Stories – Volume #2 Angel Song – A glorious collection of heavenly bodies by SQP (Volume #1) Anti-Racist Action – Volume 25 #2 April/June 2012 Art in America - September 2008, October 2008, May 2010, March 2016, June/July 2016 Artists Magazine - October 2009, September 2012, November -

The Derailment of Feminism: a Qualitative Study of Girl Empowerment and the Popular Music Artist

THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST A Thesis by Jodie Christine Simon Master of Arts, Wichita State University, 2010 Bachelor of Arts. Wichita State University, 2006 Submitted to the Department of Liberal Studies and the faculty of the Graduate School of Wichita State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts July 2012 @ Copyright 2012 by Jodie Christine Simon All Rights Reserved THE DERAILMENT OF FEMINISM: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF GIRL EMPOWERMENT AND THE POPULAR MUSIC ARTIST The following faculty members have examined the final copy of this thesis for form and content, and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts with a major in Liberal Studies. __________________________________________________________ Jodie Hertzog, Committee Chair __________________________________________________________ Jeff Jarman, Committee Member __________________________________________________________ Chuck Koeber, Committee Member iii DEDICATION To my husband, my mother, and my children iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my adviser, Dr. Jodie Hertzog, for her patient and insightful advice and support. A mentor in every sense of the word, Jodie Hertzog embodies the very nature of adviser; her council was very much appreciated through the course of my study. v ABSTRACT “Girl Power!” is a message that parents raising young women in today’s media- saturated society should be able to turn to with a modicum of relief from the relentlessly harmful messages normally found within popular music. But what happens when we turn a critical eye toward the messages cloaked within this supposedly feminist missive? A close examination of popular music associated with girl empowerment reveals that many of the messages found within these lyrics are frighteningly just as damaging as the misogynistic, violent, and explicitly sexual ones found in the usual fare of top 100 Hits. -

Riaa Gold & Platinum Awards

5/1/2016 — 5/31/2016 In May 2016, RIAA certified 65 Digital Single Awards and 26 Album Awards. Complete lists of all album, single and video awards dating all the way back to 1958 can be accessed at the NEW riaa.com. RIAA GOLD & MAY 2016 PLATINUM AWARDS DIGITAL MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE (12) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 5/13/2016 CAKE BY THE OCEAN DNCE REPUBLIC RECORDS 2 9/18/2015 5/25/2016 JUMPMAN DRAKE YOUNG MONEY/CASH 2 9/20/2015 MONEY/REPUBLIC RECORDS 5/25/2016 JUMPMAN DRAKE YOUNG MONEY/CASH 3 9/20/2015 MONEY/REPUBLIC RECORDS 5/20/2016 TRAP QUEEN FETTY WAP 300 ENTERTAINMENT/ 4 4/22/2014 ATLANTIC RECORDS 5/20/2016 TRAP QUEEN FETTY WAP 300 ENTERTAINMENT/ 3 4/22/2014 ATLANTIC RECORDS 5/20/2016 TRAP QUEEN FETTY WAP 300 ENTERTAINMENT/ 2 4/22/2014 ATLANTIC RECORDS 5/31/2016 I TOOK A PILL IN IBIZA MIKE POSNER ISLAND RECORDS 2 4/3/2015 5/11/2016 GOOD FOR YOU (FEAT A$AP SELENA GOMEZ INTERSCOPE 3 6/27/2015 ROCKY) 5/11/2016 GOOD FOR YOU (FEAT A$AP SELENA GOMEZ INTERSCOPE 2 6/27/2015 ROCKY) 5/11/2016 SAME OLD LOVE SELENA GOMEZ INTERSCOPE 2 9/16/2015 5/18/2016 DIE A HAPPY MAN THOMAS RHETT VALORY MUSIC GROUP 2 9/18/2015 5/12/2016 STRESSED OUT TWENTY ONE FUELED BY RAMEN 3 4/28/2015 PILOTS DIGITAL PLATINUM SINGLE (14) Cert Date Title Artist Label Plat Level Rel. Date 5/4/2016 TENNESSEE WHISKEY CHRIS STAPLETON MERCURY NASHVILLE 1 5/4/2015 5/3/2016 PANDA DESIIGNER DEF JAM 1 2/26/2016 www.riaa.com GoldandPlatinum @RIAA @riaa_awards MAY 2016 5/4/2016 MIDDLE FEAT. -

Order Form Full

POP ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADELE 19 (180 GR) CBS RM127.00 ADELE 21 CBS RM112.00 ADELE 25 (180 GR) XL RECORDINGS RM133.00 AMOS, TORI UNDER THE PINK (180 GR) ATLANTIC CATALOG RM127.00 AMOS, TORI UPSIDE DOWN: FM RADIO BROADCASTS BAD JOKER RM117.00 BELL, DRAKE READY STEADY GO! SURFDOG RM109.00 BENNETT, TONY & LADY GAGA CHEEK TO CHEEK POLYDOR RM122.00 BEYONCE LEMONADE (180 GR) COLUMBIA RM152.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN BELIEVE DEF JAM RM108.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN JOURNALS DEF JAM RM135.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD DEF JAM RM108.00 BIEBER, JUSTIN MY WORLD 2.0 DEF JAM RM108.00 BILLIE JOE & NORAH FOREVERLY WARNER BROS RM119.00 BUGG, JAKE ON MY ONE ISLAND RM128.00 BUGG, JAKE SHANGRI-LA ISLAND RM128.00 CHARLI XCX SUCKER ATLANTIC RM113.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT FLYING HIGH (180 GR) GET HIP RM94.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT RIBBON OF GOLD (180 GR) GET HIP RM94.00 COLLINS, PAUL - BEAT THE KIDS ARE THE SAME (180 GR) GET HIP/COLUMBIA RM106.00 COLLINS, PHIL ...BUT SERIOUSLY (180 GR) RHINO RM148.00 COLLINS, PHIL FACE VALUE (180 GR) RHINO RM119.00 COLLINS, PHIL NO JACKET REQUIRED (180 GR) RHINO RM119.00 CULTURE CLUB LIVE AT WEMBLEY - WORLD TOUR 2016 CLEOPATRA RM122.00 CYRUS, MILEY YOUNGER NOW RCA RM120.00 DARE, DOUGLAS AFORGER (CLEAR VINYL) ERASED TAPES RM137.00 DUFFY ROCKFERRY MERCURY RM108.00 EILISH, BILLIE DON'T SMILE AT ME (COLOR) INTERSCOPE RM114.00 EKKO, MIKKY TIME RCA RM100.00 EURYTHMICS GREATEST HITS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM172.00 FALL OUT BOY INFINITY ON HIGH (180 GR) ISLAND RM145.00 FURTADO, NELLY THE RIDE (180 GR) NELSTAR MUSIC RM128.00 GO-GO'S LET'S HAVE A PARTY: -

An Open Handbook of Collective College Theory

Plymouth State Digital Commons @ Plymouth State Open Educational Resources Open Educational Resources 2018 The Student Theorist: An Open Handbook of Collective College Theory Abby Goode Plymouth State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.plymouth.edu/oer Recommended Citation Goode, Abby, "The Student Theorist: An Open Handbook of Collective College Theory" (2018). Open Educational Resources. 18. https://digitalcommons.plymouth.edu/oer/18 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at Digital Commons @ Plymouth State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Educational Resources by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Plymouth State. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. The Student Theorist: An Open Handbook of Collective College Theory The Student Theorist: An Open Handbook of Collective College Theory Abby Goode Public Commons Publishing Plymouth The Student Theorist: An Open Handbook of Collective College Theory by Abby Goode is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. This book was produced using Pressbooks.com, and PDF rendering was done by PrinceXML. Contents Copyright and Authorship 1 Preface to the 2018 Edition 3 PART I. PSYCHOANALYSIS 1. The Uncanny Representation of Sandy Eyes 9 and Castration Amelia Berube, Cassandra Gray, Timothy Mooneyhan, John J. Bush III, and Paige Schoppmann 2. Let's Talk about Death, Baby! 13 Paige Schoppmann 3. Freud, Incest, and Hamlet 20 Ryan French 4. Nautical Nonsense 23 Carmen Maura 5. Scarred for Life 25 Samantha Latos 6. -

Ghosts of Mathare White Cane Label Rihanna

OCTOBER 12, 2007 | WWW.REPORTERMAG.COM GHOSTS OF MATHARE THE BEAUTY AND THE HORROR WHITE CANE LABEL STYLE GUIDE FOR THE BLIND RIHANNA GOOD GIRL GONE BAD EDITOR’S NOTE TABLE OF CONTENTS OCTOBER 12, 2007 | Vol. 57, Issue 06 UntYinG the GordiAN Knot EDITOR IN CHIEF Jen Loomis Clad in a pair of black dress pants and a slightly faded long-sleeved shirt (also black), Steve Woz- MANAGinG Editor Adam Botzenhart niak stands before a crowded room with squinted eyes and a big smile hiding behind his scraggly COPY Editor Veena Chatti salt-and-pepper beard. His wrist is held high in the air, wrapped in a strange device— not exactly a NEWS EDITOR Joe McLaughlin watch, but watch-shaped, and containing two transistor-like decorative elements. The accessory’s LEISURE EDITOR Casey Dehlinger charm lies in how unassuming it is. FEATURES EDITOR Laura Mandanas SPORTS/VIEWS EDITOR Geoff Shearer Wozniak’s wrist, as well as the hand attached to it, waves emphatically; the man is sketching the switches and lights of a PC board in the air, and is caught up in the excitement of the moment. He WRITERS David Carter, Michael Conti, Casey Dehlinger, speaks with a sort of practiced uneasiness, taking great care to space out the words within each Laura Mandanas, Tiffany Mason, Ryan Metzler, Reid Muntz, sentence, but somehow running the end of that sentence straight into the beginning of the next. Sarai Oviedo, Mike Percia, Geoff Shearer, Lacey Senese, Madeleine Villavicencio You can barely see his eyes, he’s squinting so hard. Yet somehow, they still shine as bright as stars when he gets going. -

Female Empowerment Female Cencere Richardson, Michael Suarez, Steven Dumeng

March Edition Cardinal 2019 Women’s History montH “For me, it really is about the “Remember no one can “I don't fear being outspoken. The only thing I fear is losing self-acceptance... the more time make you feel inferior with- that I spend really accepting and out your consent.” my sense of integrity or losing sight of the values on which I allowing myself to be exactly - Eleanor Roosevelt guide my life. So I don't think where I am, the faster it is I it's particularly brave or unu- move towards what I wanna be sual for me to speak out.” doing.” - Constance Wu - Tracee Ellis Ross “Do the one thing you think you cannot do. Fail at it. Try again. Do better the second time. The “Nothing is absolute. Everything only people who never tumble "Let us make our future now, changes, everything moves, eve- are those who never mount the and let us make our dreams rything revolves, everything flies high wire. This is your moment. tomorrow's reality." and goes away.” Own it.” - Frida Kahlo - Oprah Winfrey - Malala Yousafzai Newspaper Contributors Editor-In-Chief - David Matos Writers– David Matos, Michael Centeno, Andrew Cabram, Kughan Gunaratnam, Jaydn Davis, Female Empowerment Cencere Richardson, Michael Suarez, Steven Dumeng This edition is also available at www.lasalleacademy.org MARCH EDITION Page 2 Women’s History montH It’s finally March which also means it’s finally that time of year when we honor and appreciate the women of the past that made history and the women of the present that are mak- ing history.