'Tiger King' Shines Light on an Endangered Species Act Quirk by Stephanie Clark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3Rd Grade ELA to Proficiency and Beyond!

3rd Grade ELA To Proficiency and Beyond! Table of Contents • Glossary of Academic Terms • Annotation Guide • Vocabulary Practice Items • Comprehension Practice Items • Answer Guide Glossary of Academic Terms accurate – exact; correct acquire– to learn or gain control of something analyze – to examine in detail the structure or elements of a text annotate – add notes to text to clarify understanding antonym – a word opposite in meaning to another appropriate– relevant argument – a set of reasons to persuade that something is a correct or right choice attributes - characteristics author’s point of view – the perspective or feeling of the author about characters, ideas, details author’s purpose – the author’s reason for writing/creating text or features in text background knowledge – information the reader has outside of the text casts – creates, brings to the reader’s attention challenges – problems within the text central idea – the message the author is trying to convey throughout the text; the author’s main point; the author’s claim characterization – the construction of literary characters; the description of characters cite – to quote text claim – a statement of truth which can be backed up by reasons and evidence clarify – to make clear climax – the highest point of action/tension in a literary/fiction text coherent – makes sense from start to finish; logical compare – state similarities between things/ideas concluding statement/ section – conclusion, final section conflict- a struggle between two ideas/forces/characters in literature -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Bovine Benefactories: an Examination of the Role of Religion in Cow Sanctuaries Across the United States

BOVINE BENEFACTORIES: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN COW SANCTUARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES _______________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________ by Thomas Hellmuth Berendt August, 2018 Examing Committee Members: Sydney White, Advisory Chair, TU Department of Religion Terry Rey, TU Department of Religion Laura Levitt, TU Department of Religion Tom Waidzunas, External Member, TU Deparment of Sociology ABSTRACT This study examines the growing phenomenon to protect the bovine in the United States and will question to what extent religion plays a role in the formation of bovine sanctuaries. My research has unearthed that there are approximately 454 animal sanctuaries in the United States, of which 146 are dedicated to farm animals. However, of this 166 only 4 are dedicated to pigs, while 17 are specifically dedicated to the bovine. Furthermore, another 50, though not specifically dedicated to cows, do use the cow as the main symbol for their logo. Therefore the bovine is seemingly more represented and protected than any other farm animal in sanctuaries across the United States. The question is why the bovine, and how much has religion played a role in elevating this particular animal above all others. Furthermore, what constitutes a sanctuary? Does -

Volume 7 of Jury Trial

Case 5:18-cr-00227-SLP Document 143-6 Filed 03/23/20 Page 1 of 56 1 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 2 FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF OKLAHOMA 3 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) 4 ) ) 5 Plaintiff, ) ) 6 vs. ) CASE NO. CR-18-227-SLP ) 7 ) ) 8 JOSEPH MALDONADO-PASSAGE, ) ) 9 ) ) 10 Defendant. ) 11 12 * * * * * * 13 VOLUME VII OF VII 14 TRANSCRIPT OF JURY TRIAL 15 BEFORE THE HONORABLE SCOTT L. PALK 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE 17 APRIL 2, 2019 18 * * * * * * * 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Proceedings recorded by mechanical stenography; transcript produced by computer- aided transcription. Emily Eakle, RMR, CRR United States Court Reporter U.S. Courthouse, 200 N.W. 4th St. Oklahoma City, OK 73102 * 405.609.5403 Case 5:18-cr-00227-SLP Document 143-6 Filed 03/23/20 Page 2 of 56 2 1 APPEARANCES 2 Ms. Amanda Maxfield-Green and Mr. Charles Brown, Assistant United States Attorneys, U.S. Attorney's Office, 210 West Park 3 Avenue, Suite 400, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102, appearing for the United States of America. 4 Mr. William Earley and Mr. Kyle Wackenheim, Assistant United 5 States Public Defenders, 215 Dean A. McGee, Suite 124, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102, appearing for the defendant. 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Emily Eakle, RMR, CRR United States Court Reporter U.S. Courthouse, 200 N.W. 4th St. Oklahoma City, OK 73102 * 405.609.5403 Case 5:18-cr-00227-SLP Document 143-6 Filed 03/23/20 Page 3 of 56 1054 1 INDEX PAGE 2 Closing argument by the Government.....................1055 3 Closing argument by the Defense........................1078 4 Final closing by the Government........................1095 5 Verdict................................................1101 6 Reporter's Certificate.................................1107 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Emily Eakle, RMR, CRR United States Court Reporter U.S. -

Letter to Shareholders

April 21, 2020 Fellow Shareholders, In our 20+ year history, we have never seen a future more uncertain or unsettling. The coronavirus has reached every corner of the world and, in the absence of a widespread treatment or vaccine, no one knows how or when this terrible crisis will end. What’s clear is the escalating human cost in terms of lost lives and lost jobs, with tens of millions of people now out of work. At Netflix, we’re acutely aware that we are fortunate to have a service that is even more meaningful to people confined at home, and which we can operate remotely with minimal disruption in the short to medium term. Like other home entertainment services, we’re seeing temporarily higher viewing and increased membership growth. In our case, this is offset by a sharply stronger US dollar, depressing our international revenue, resulting in revenue-as-forecast. We expect viewing to decline and membership growth to decelerate as home confinement ends, which we hope is soon. By helping people connect with stories they love, we are able to provide comfort and escape as well as a sense of community during this pandemic. So our focus has been on maintaining the quality of our service while our employees around the world adapt to working from home. For the most part, this has gone smoothly. Our product teams, for example, have been relatively unaffected. As a precaution, we have temporarily reduced the number of product innovations we try, while continuing to release features that we know will add meaningful value for our members, such as improved parental controls. -

SUPPLEMENTORY READER-VISTAS CLASS-XII LESSON NO.02 the TIGER KING by KALKI CHARACTERS-1-The Tiger King Sir Jilani Jung Jung Bhad

SUPPLEMENTORY READER-VISTAS CLASS-XII LESSON NO.02 THE TIGER KING BY KALKI CHARACTERS-1-The Tiger King Sir Jilani Jung Jung Bhadur 2-Astrologer 3-Diwan 4-British Officer GIST OF THE LESSON The Maharaja Sir Jilani Jung Jung Bhadur was called “Tiger King”.When he was just 10 days old he asked intelligent questions to the astrologers and was told that he would be killed by a tiger. He uttered “Let tigers beware!” No other miracle took place, the child grew like any other Royal child drinking white cow’s milk, taught by an English tutor, looked after by an English nanny and watched English film. When he was 20, he was crowned as king. It was then the prediction of his death by the tiger reached the Maharaja’s ear and he in turn to safe guard himself killed a tiger and being thrilled he told the astrologer who replied that he can kill 99 tigers but should be careful with the 100th. From then on he started killing tiger and none was allowed to hunt tigers. A high-ranking British officer visited the state that was fond of hunting tiger and his wish was declined. The officer requested for getting a photograph with a tiger killed by Maharaja and this request was rejected. So to please the officer’s wife he sent 50 diamond rings expecting that she would take 1 or 2 instead she kept all the rings costing 3 lakh rupees and sent ‘thanks’ to the Maharaja. But his state was secured. In 10 years he killed 70 tiger and didn’t find any in Pratibandapuram so he decided to marry a girl from royal state which had more tigers to complete his target. -

Terrain of the Aran Islands Karen O'brien

Spring 2006 169 ‘Ireland mustn’t be such a bad place so’: Mapping the “Real” Terrain of the Aran Islands Karen O’Brien Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple of Inishmaan (1996) responds to and encodes the complexities of representational and ecological issues surrounding life on the rural landscape of the Aran Islands. The three islands that constitute the Aran Islands—Inisheer, Inishmaan, and Inishmore—occupy a unique and dual position of marginality and liminality; they not only reside off the border of the western coast of Ireland but also inhabit an indeterminate space between America and Europe. The archipelagos are described by Irish poet Seamus Heaney as a place “Where the land ends with a sheer drop / You can see three stepping stones out of Europe.”1 Inishmaan employs three strategic interrogations—representation, structure, and aesthetics—that coincide with the project of collaborative ecology. The first strategy juxtaposes two contrasting representations of Ireland’s 1930s rural west, problematizing the notion of a definable Irishness in relation to the unique Arans landscape. Inishmaan revolves around the filming of the American documentary Man of Aran (1934), which claims authenticity in its representation of actual island residents. McDonagh’s depiction of the Aran community, however, contradicts the documentary’s poetic vision of the Aran Islands as a pristine landscape. In scene eight, for example, the screening of Man of Aran does not reflect a mirror image of the Aran residents represented in the play; the film, contrarily, incites mockery. Despite its claim of historical authenticity and authority, the documentary proves fictional. Inishmaan contests the legitimacy of Man of Aran explicitly as well as a history of romanticized notions of western Irish identity implicitly. -

Dear Ms. Olmstead, Netflix's Tiger King Is Calling Critical Attention To

Dear Ms. Olmstead, Netflix’s Tiger King is calling critical attention to the abuse and neglect endured by big cats and other wild animals used for entertainment— progress that will be undone if real wild animals are used in Universal Content Production’s upcoming Joe Exotic series. When wild animals are used for entertainment—whether by roadside zoo operators like those featured in Tiger King or for the film and TV industry by trainers—they suffer. Most wild animals do everything that they can to avoid humans, but those used by trainers are forced into close proximity with their captors and are also deprived of their families, their freedom, and anything remotely natural to them. Animals used in the entertainment industry are routinely separated from their mothers prematurely and denied the maternal care that they need for normal development, which can result in extreme physical and psychological distress. When no longer deemed "useful," many animals used for film or TV are dumped at seedy roadside zoos, including the chimpanzees seen in Tiger King. Investigations have uncovered animals being whipped and kept in deplorable conditions by animal suppliers. Wild animals are exactly that—they’re wild, and no amount of training can ever completely override their natural instincts, making them extremely dangerous. They belong in their natural habitats or otherwise at reputable sanctuaries—not in animal training compounds, on green screen stages, or at roadside zoos. Reputable sanctuaries never breed or sell wild animals, never allow public encounters with them, and never cart them to and from film and TV sets. -

Course Outline 2020-21

COURSE OUTLINES Taking care of process takes care of the outcomes SUBJECT: ENGLISH NAME OF THE ENDURING LEARNING TARGETS START DATE END DATE REQUIRED UNIT/CONCEPT/SKILLS UNDERSTANDING FOR (dd/mm/yyyy) (dd/mm/yyyy) NUMBER THE UNIT OF DAYS Classified and Students communicate 1.Display awareness about the 12.2.2020 19.2.2020 5 Commercial Ads information about a format and writing style of (Advanced Writing product, event or service classified and display Skills) concisely and as advertisements. Short Composition effectively as possible so 2. Implement and execute formal as to showcase a product. conventions. They are able to explain the use of Propaganda Techniques in Advertisements. Notice Writing Students are aware about 1. Draft Notices according to the 20.2.2020 24.2.2020 2 (Advanced Writing formal language as used information given. Skills) in official 2. Integrate various value points Short Composition communications. They and information in a concise are aware about the need manner. for brevity in official 3. Write notices in the given communications. They format and within the specified are aware of and word limit recognize the different forms of Notices and their uses. Page 1 of 173 My Mother at Sixty Students appreciate 1.Provide strong textual evidence 25.2.2020 27.2.2020 3 Six (Poem) poetry as a means for in support of assumptions, highlighting the pain of arguments and observations. separation from the near 2. Identify, analyze and explain and dear ones and the important metaphors, symbols necessity to understand and figures of speech and and accept such losses in techniques like Enjambment life. -

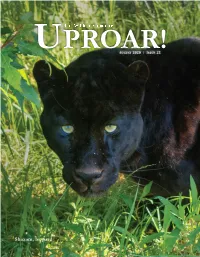

UPROAR!August 2020 | Issue 25

The Wildcat Sanctuary UPROAR!August 2020 | Issue 25 Shazam, leopard The Wildcat Sanctuary PROAR! Callie, tiger U August 2020 | Issue 25 Tammy Thies From th Founder & Executive Director e Founder Julie Hanan Contributor Carissa L. Winter Graphic Designer Photography by Judson Tharin, staff, interns and volunteers. Mission: Provide natural sanctuary to wild cats in need and inspire change to end the captive wildlife crisis. Vision: Help create a world where wild animal sanctuaries are no longer needed. e Wildcat Sanctuary is a tax-exempt charity under the IRS code section 501c3, our federal tax ID number is 22-3857401. e Wildcat Sanctuary PO Box 314 • Sandstone, MN 55072 320-245-6871 Follow us on: Copyright © e Wildcat Sanctuary. All Rights Reserved. 2 August 2020 WildcatSanctuary.org Fro m the Founder Learning to expect the unexpected ever in my wildest dreams did I think I’d be writing to you with the world in the state it’s in today. The global pandemic has changed our lives forever. And the riots in our home state, from the unjust death of Na person in police custody, is rippling around the world. If that isn’t enough to make your heart heavy, then add the sensationalism and media frenzy over the Netflix series Tiger King. That docuseries propelled many dealers and breeders into pop culture and the mainstream. It’s hard to know even where to start. My heart hurts So many people are affected, and the heaviness has touched us all in some way. Whether it be the loss of a job, or worst of all the loss of a life, it cannot help but weigh on us all. -

Published As Perspective in on Culture: the Open Journal for the Study of Culture (ISSN 2366-4142)

Published as _Perspective in On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture (ISSN 2366-4142) OF ANIMAL LOVE AND ABUSE: EXPLORING AMBIVALENT HUMAN-ANIMAL RELATIONSHIPS IN TIGER KING (2020) DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC LIZA B. BAUER [email protected] Liza B. Bauer, M.A. is a doctoral researcher at the International Graduate Centre for the Study of Culture (GCSC) and holds a graduate scholarship from the Justus Liebig University Giessen. She studied Anglophone Studies in Marburg and Giessen and is currently working on her dissertation entitled Livestock in the Laboratory of Literature: The Cultural and Ethical Work of Farm Animal Representations in Anglophone Literary Thought Experiments. She further functions as one of the coordinators of the interdisciplinary research section “Human-Animal Studies” at her university’s Graduate Centre for the Study of Social Sciences, Business, Economics and Law (GGS) and works as an academic assistant for the International PhD program “Literary and Cultural Studies” (IPP) at the GCSC. KEYWORDS human-animal relations, tiger king, COVID-19, human-animal studies, pet-keeping, anthropocentrism PUBLICATION DATE Issue 9, September 3, 2020 HOW TO CITE Liza B. Bauer. “Of Animal Love and Abuse: Exploring Ambivalent Human-Animal Relationships in Tiger King (2020) during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture #9 (2020). <http://geb.uni- giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2020/15447/>. Permalink URL: <http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2020/15447/> URN: <urn:nbn:de:hebis:26-opus-154477> On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture Issue #9 (2020): Love www.on-culture.org http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2020/15447/ Of Animal Love and Abuse: Exploring Ambivalent Human-Animal Relationships in Tiger King (2020) during the COVID-19 Pandemic _Abstract On March 20, 2020, Netflix launched a new hit. -

Astroscientist Follows the Light in Search for Life on Other Planets

WEEK OF MAY 28-JUNE 3, 2020 www.FloridaWeekly.com Vol. X, No. 30 • FREE INSIDE: How binge watching has ALSO: How we are all in become a cultural touchstone in this together, and we are all the season of the virus. A10 X watching — together. A11 X Back on the water? Be sure to watch for manatees. A4 X The pandemic bump \binj\ In the working world, dedicated role players must noun; a) a shortshort periodperiod devoteddevoted toto indulgingindulging inin anan be prepared when called activity to excess. b) anan unrestrainedunrestrained andand oftenoften upon. A13 X excessive indulgence. c) an actact ofof excessiveexcessive oror compulsive consumption (as of foodfood oror drinking).drinking). “He went on a bingebinge andand stayedstayed upup allall night.”night.” verb; a) indulge in an activityactivity toto excess.excess. “Some“Some viewers cannot help bingeing onon episodesepisodes ofof Ozark.” Observe the birds Use care when sharing the shore with nests, chicks. A3 X ILLUSTRATION BY ERIC RADDATZ / FLORIDA WEEKLY BY ERIC RADDATZ ILLUSTRATION Astroscientist follows the light in search for life on other planets BY JAY MACDONALD on other planets — and perhaps identify FGCU360 Magazine a planetary refuge should ours become Collector’s Corner uninhabitable. Every bit of history leaves its Astroscientist Derek Buzasi’s mission in What the heck is asteroseismology? The mark on a piece. A20 X life is to see the light, even if he has to hunt fun-loving Mr. Buzasi, a Whitaker Emi- through the night sky using land-based nent Scholar at FGCU, participated in and orbiting telescopes and technologies the late 20th-century breakthrough that Download to do so.