Oral History: from Fact Finding to History Shaping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Science Society Annual Meeting San Diego, California 15-18 November 2012

History of Science Society Annual Meeting San Diego, California 15-18 November 2012 Session Abstracts Alphabetized by Session Title. Abstracts only available for organized sessions. Agricultural Sciences in Modern East Asia Abstract: Agriculture has more significance than the production of capital along. The cultivation of rice by men and the weaving of silk by women have been long regarded as the two foundational pillars of the civilization. However, agricultural activities in East Asia, having been built around such iconic relationships, came under great questioning and processes of negation during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as people began to embrace Western science and technology in order to survive. And yet, amongst many sub-disciplines of science and technology, a particular vein of agricultural science emerged out of technological and scientific practices of agriculture in ways that were integral to East Asian governance and political economy. What did it mean for indigenous people to learn and practice new agricultural sciences in their respective contexts? With this border-crossing theme, this panel seeks to identify and question the commonalities and differences in the political complication of agricultural sciences in modern East Asia. Lavelle’s paper explores that agricultural experimentation practiced by Qing agrarian scholars circulated new ideas to wider audience, regardless of literacy. Onaga’s paper traces Japanese sericultural scientists who adapted hybridization science to the Japanese context at the turn of the twentieth century. Lee’s paper investigates Chinese agricultural scientists’ efforts to deal with the question of rice quality in the 1930s. American Motherhood at the Intersection of Nature and Science, 1945-1975 Abstract: This panel explores how scientific and popular ideas about “the natural” and motherhood have impacted the construction and experience of maternal identities and practices in 20th century America. -

Celebrating the Oral History Class of 2016 the 20152016 School Year Re

Newsletter June 2016 Contents: From the Director Oral History in Action From the Archives News About OHC Coming Up Helen Gahagan Douglas interviewed by OHC in the 1970s From the Director From the Director: Celebrating the Oral History Class of 2016 The 20152016 school year recently wrapped up at the Oral History Center with what has become a new and thriving tradition: the annual Oral History Graduation! In late April or early May over the past four years, we have hosted our very commencement ceremony in which we celebrate the oral histories completed over the past year. This special event gives us an opportunity to thank our interviewees Three Narrators from our Rosie the Riveter for the often considerable time they Oral History Project at our recent event give to our projects and to the sponsors who make those projects possible. This year we were especially honored to have many of our interviewees in attendance... [Read more] Back to Top Oral History in Action Welcome to Todd Holmes, Our Newest Historian / Interviewer We are proud to announce the arrival of a new interviewer at the Oral History Center, Todd Holmes. Todd is joining us from the Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University, where he was a researcher and Affiliated Scholar. Todd completed his PhD from Yale University, where he studied the political history of California and its impact on national politics in the late20th century. [Read more] Todd Holmes, OHC Historian/Interviewer Exploring Law and Educational Finance Reform: Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman Few intellectual partnerships have been as durable and productive as the one forged between Berkeley Law professors Jack Coons and Stephen Sugarman over the past half century. -

Columbia University Center Fororal History

Columbia University Center for Oral History TEN-YEAR REPORT “The great strength of oral history is its ability to record memories in a way that honors the dignity and integrity of ordinary people.” —Mary Marshall Clark, Director, Columbia Center for Oral History Letter from the Director .............................. 1 CCOH Mission and History ............................ 3 Research ........................................ 5 September 11, 2001, Oral History Projects . 5 After the Fall, CCOH Director Book . 7 Apollo Theater Oral History Project . 7 Guantánamo Bay Oral History Project Video Interviews in London, England . 8 Atlantic Philanthropies Oral History Project . 8 Council on Foreign Relations Oral History Project . 9 Elizabeth Murray Oral History of Women in the Visual Arts . 9 Guantánamo Bay Oral History Project . 9 Rule of Law Oral History Project . 10 United Nations Intellectual History Project . 10 Biographical Interviews . 10 John W. Kluge (1914–2010) . 10 William T. Golden (1909–2007) . 11 Robert P. DeVecchi . 11 Archive ......................................... 13 Oral History Collections Portal . 13 CCOH’s New Website . 13 Digital Exhibitions . 14 Preservation . 15 Education ........................................ 17 Oral History Master of Arts . 17 Summer Institute . 17 Workshops and Events . 19 Conference Presentations . 21 Consultations . 21 Oral History Training for Educators and Human Rights Activists . 22 Online Outreach . 22 Publications ...................................... 23 Staff, Supporters, and Advisory Board .................... 25 Staff and Interviewers . 25 Advisory Committee . 26 Supporters . 27 Contact Us ............................ inside back cover 1 Letter from the Director Ten years ago, in June 2001, I was named director of the Oral History Research Office . Having worked for some years at Columbia, I knew my way around and looked forward to some time to plan the future . -

The Myth of Nuclear Deterrence’’

A THREE-PART DEBATE PART I A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF ‘‘THE MYTH OF NUCLEAR DETERRENCE’’ Derrin Culp [Editor’s note: The Nonproliferation Review presents here a debate in three parts, featuring a critique by Derrin Culp of Ward Wilson’s 2008 award-winning article ‘‘The Myth of Nuclear Deterrence,’’ a response from Wilson, and a finally a closing counter from Culp. We invite readers to join the debate via letters to the editor ([email protected]).] Several years ago, Ward Wilson presented in this journal a wide-ranging challenge to what every generation of national security scholars and practitioners since the end of World War II has been taught about nuclear weapons. He asserted that nuclear deterrence amounts to far less than its proponents have claimed and provocatively suggested that nuclear deterrence is a myth. Relying upon both empirical and theoretical objections to nuclear deterrence, he concluded that its failures were clear-cut and indisputable, whereas its successes were speculative. Yet in spite of a flourishing trade in scholarly articles, think tank reports, blog posts, and opinion pieces concerning nuclear deterrence, nobody*including nuclear weapons scholars*has ventured more than a limited critique of Wilson’s essay. There are, however, serious shortcomings in Wilson’s arguments*deficiencies that make his essay an unpersuasive brief against nuclear deterrence. Wilson’s thesis could be correct. His arguments, however, are unlikely to persuade any skeptical members of Congress, upon whom future progress in arms control -

The Oral History Bibliography

An Oral History Bibliography *** A Research Guide by the Columbia University Center for Oral History 2 Table of Contents I. Manuals and Practical Guides 3 II. Methodology and Theory 4 III. Fieldwork, Projects, Processing and Distribution 8 IV. Community Projects 10 V. Ethics and Responsibilities 12 VI. African-American Studies 13 VII. Anthropology and Folklore 15 VIII. Body Narratives 17 IX. Education 18 X. Human Rights and the Law 19 XI. Memory 22 XII. Narrative, Orality and History 25 XIII. Psychology and Trauma 27 XIV. Sociology 29 XV. Social History 30 XVI. Women & Gender Studies 33 XVII. Journals 36 XVIII. Video and Audio Recordings 37 XIX. Selected Examples of Oral History-based Texts 38 *** This comprehensive oral history bibliography was developed for the public’s use by the Columbia University Center for Oral History in 2009 by Project Coordinator Elizabeth Grefrath. Research Assistants Kaley Bell and Jared Rosenfeld generously assisted on this project. Bibliographic citations were developed through a process of cataloguing office-housed articles. *** The Columbia University Center for Oral History is one of the world’s leading centers for the practice and teaching of oral history. Our archive, located in the Columbia University Libraries and open to the public, holds more than 8,000 text and audio interviews on a wide variety of subjects. Our mission is to record unique life histories, documenting the central historical events and memories of our times, and to teach and do research across the disciplines. 3 I. Manuals and Practical Guides Baum, Willa K. Transcribing and Editing Oral History. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 1977. -

The Development of Oral History in the United States: the Evolution Toward Interdisciplinary

e - ISSN 2175 - 1803 The Development of Oral History in the United States: the evolution toward interdisciplinary Abstract This article discusses the development of oral history David King Dunaway in the United States and how this has led the field to Professor at University of New Mexico. becoming interdisciplinary in interesting and useful USA ways. It traces its origins in the 17th century and [email protected] explains its establishment as method (oral data collection), a subfield of history (oral historiography) and a resource for teachers, communities, and researchers of all kinds (oral history). The author describes the practical applications of oral history in other fields such as anthropology, education/ teaching, ethnic studies/ethnohistory/American studies, folklore, gerontology, legal studies, literary history, media studies and media production, and women and gender studies. A review of oral history guides is also given. The article ends with an update on how oral historians are coping with the new, anti- intellectual orientation of President Trump and his right-wing agenda. Keywords: Oral History. USA. Oral Data Collection. History-Telling. To cite this article: DUNAWAY, David King. The Development of Oral History in the United States: the evolution toward interdisciplinary. Revista Tempo e Argumento, Florianópolis, v. 10, n. 24, p. 115 - 135. abr./jun. 2018. DOI: 10.5965/2175180310242018115 http://dx.doi.org/10.5965/2175180310242018115 Revista Tempo e Argumento, Florianópolis, v. 10, n. 24, p. 115 - 135. abr./jun. 2018. p.115 Tempo The Development of Oral History in the United States: the evolution toward interdisciplinary David King Dunaway & Argumento O Desenvolvimento da história oral nos Estados Unidos: a evolução rumo à interdisciplinaridade Resumo Este artigo discute o desenvolvimento da história oral nos Estados Unidos e como isto levou o campo a se tornar interdisciplinar em modos interessantes e úteis. -

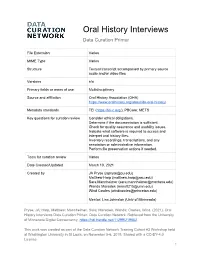

Oral History Interviews Data Curation Primer

Oral History Interviews Data Curation Primer File Extension Varies MIME Type Varies Structure Textual transcript accompanied by primary source audio and/or video files Versions n/a Primary fields or areas of use Multidisciplinary Source and affiliation Oral History Association (OHA) https://www.oralhistory.org/about/do-oral-history/ Metadata standards TEI (https://tei-c.org/); PBCore; METS Key questions for curation review Consider ethical obligations. Determine if the documentation is sufficient. Check for quality assurance and usability issues. Indicate what software is required to access and interpret oral history files. Inventory recordings, transcriptions, and any annotation or administrative information. Perform file preservation actions if needed. Tools for curation review Varies Date Created/Updated March 10, 2021 Created by JA Pryse ([email protected]) Matthew Harp ([email protected]) Sara Mannheimer ([email protected]) Wanda Marsolek ([email protected]) Wind Cowles ([email protected]) Mentor: Lisa Johnston (Univ of Minnesota) Pryse, JA; Harp, Matthew; Mannheimer, Sara; Marsolek, Wanda; Cowles, Wind. (2021). Oral History Interviews Data Curation Primer. Data Curation Network. Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, https://hdl.handle.net/11299/219052. This work was created as part of the Data Curation Network Training Cohort #3 Workshop held at Washington University in St Louis, on November 5-6, 2019. Shared with a CC-BY-4.0 License. 1 Oral Histories Data Curation Primer Table of Contents: 1.0 Description of format 2.0 Examples: What does a typical oral history dataset look like? 3.0 Workflow 3.1 Ethical issues 3.2 Documentation 3.3 Applicable metadata standards, core elements, and readme requirements: 3.4 Technical issues 3.5 Check Files 4.0 What to look for to make sure this file meets FAIR principles 5.0 Documentation of curation process: What do you capture from curation process 6.0 Bibliography 7.0 Appendix 1 - Best Practices: Pre-production, Production, Post-production 8. -

Ethnohistory of the Qizilbash in Kabul: Migration, State, and a Shi'a Minority

ETHNOHISTORY OF THE QIZILBASH IN KABUL: MIGRATION, STATE, AND A SHI’A MINORITY Solaiman M. Fazel Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology Indiana University May 2017 i Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee __________________________________________ Raymond J. DeMallie, PhD __________________________________________ Anya Peterson Royce, PhD __________________________________________ Daniel Suslak, PhD __________________________________________ Devin DeWeese, PhD __________________________________________ Ron Sela, PhD Date of Defense ii For my love Megan for the light of my eyes Tamanah and Sohrab and for my esteemed professors who inspired me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This historical ethnography of Qizilbash communities in Kabul is the result of a painstaking process of multi-sited archival research, in-person interviews, and collection of empirical data from archival sources, memoirs, and memories of the people who once live/lived and experienced the affects of state-formation in Afghanistan. The origin of my study extends beyond the moment I had to pick a research topic for completion of my doctoral dissertation in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University. This study grapples with some questions that have occupied my mind since a young age when my parents decided to migrate from Kabul to Los Angeles because of the Soviet-Afghan War of 1980s. I undertook sections of this topic while finishing my Senior Project at UC Santa Barbara and my Master’s thesis at California State University, Fullerton. I can only hope that the questions and analysis offered here reflects my intellectual progress. -

2019 MAC Oral History Poster V1

Campus as Laboratory: AN ORAL HISTORY OF MSU'S CAMPUS ARCHAEOLOGY PROGRAM Autumn M. Painter and A.L. McMichael Michigan State University Archaeology Web Presence Timeline oralhistory.campusarch.msu.edu By the time Dr. Lynne Goldstein retired and Oral History from Michigan State University’s Department of Anthropology in 2018, she had gathered 22 years’ worth of stories We argue that oral history is a genre of and experience. Among these are the origins and development of the Campus Archaeology Founding of CAP documentation that should augment traditional Program (CAP), which continues to offer 2007 students both field and lab experience. publications in recording the historiography of We scheduled several conversations, rather than trying to capture all of Lynne’s stories at once. We started with a list of archaeological projects, teams, and sites. broad categories that seemed pertinent to historical research, and left the interview Terry Brock questions open-ended enough that Lynne Campus Archaeologist 2007 - 2010 could help shape the narrative. We used Audacity software on a laptop with a Zoom Handy Mic to record and edit the data in LEADR. Some example research questions: Chris Stawski •“Start with a little bit about the origins or the beginnings of Campus Archaeology Campus Archaeologist Photos, from left: Fragmented doll 2010 - 2011 head found on campus in privy here at MSU.” during 2015 field season. Center: •“What makes MSU ideal for this particular type of program?” The CAP field school and crew •“Have there been any favorite projects or projects that stand out to you?” excavating midden near the administration building in 2015. -

AMH4930, Oral History, Ortiz

Oral History AMH 4930/5930 Paul Ortiz, Professor of History Director, Samuel Proctor Oral History Program Department of History, University of Florida Spring Semester, 2020 Thursdays, 11:45 to 2:45 CSE E220 This seminar is an introduction to the theory and practice of oral history. We will study the craft of oral history and explore the intellectual development of this discipline. This interdisciplinary course will study the burgeoning impact of oral history and historical memory in truth commissions, social documentaries, digital archives, public museums, web sites, national and international moments of commemoration, and other contexts. We will examine the relationship between power and memory, and the role of class, gender, and racial inequalities in shaping living histories that become enshrined as national “truths.” Students will learn to use oral history to become more effective interviewers, researchers and writers in various fields including history, education, journalism, film, radio, as well as ethnography. We will study the impact oral history has had on US, Latin American, European, and African histories and texts. Spoken memories have constituted the foundations of histories throughout the past several millennia. As Studs Terkel observed, “People are hungry for stories. It’s part of our very being. Storytelling is a form of history, of immortality too. It goes from one generation to another.” Oral history has reemerged as a serious field of inquiry even as the written—or so-called documentary—record has been subjected to increasing skepticism. At the same time, oral interviews and testimonies have been used in recent decades to uncover stories of “ordinary people,” in the United States as well as forgotten or disappeared events. -

April 2021 Newsletter

Vol.Vol. 1 Issue1 Issue 7 20217 2021 April 24 - May 3: Fifth Avenue Arts Festival July 12: Mississippi Freedom Project trip Check the SPOHP Website for upcoming updates. The Samuel Proctor Oral History Program relies on the guidance and support of our growing network of sustainers. If you are an alumni or you have a story that you want to share, please let us know! Whatever the case, thank you for being a member of the SPOHP community. We look forward to continuing to provide you with exciting updates about our students’ research! Gainesville, FL 32611 University of Florida P.O. Box 115215 241 Pugh Hall Oral History Program The Samuel Proctor The Samuel Proctor Oral History Program In This Issue: A Message from the Director.................... 02 Announcements............................................ 03 Projects..............................................................04 Awards...............................................................15 Podcast Highlights........................................16 Student Activities...........................................17 SPOHP Grads...................................................18 Save the Date....................................................20 20 Samuel Proctor Oral History Program Newsletter Vol. 1 Issue 7 2021 Abby Lovett Abby Lovett is a third-year history major who will graduate from the University of Florida this spring. She plans to continue her work with SPOHP next year while she applies to graduate school for history. Marianne Quijano Dear Friend of the Samuel Proctor Oral History Program, Marianne is a Ph.D. student specializing in modern Latin American History. For her This has been the most challenging year in the history of the doctoral research, Marianne plans to research Samuel Proctor Oral History Program (SPOHP). Our program histories of health and radical politics in Central transitioned to a completely new way of learning. -

Russian Empire-Building and the Kazakh Kinship System: the Chala-Qazaqs of the Kazakh Steppe

RUSSIAN EMPIRE-BUILDING AND THE KAZAKH KINSHIP SYSTEM: THE CHALA-QAZAQS OF THE KAZAKH STEPPE Nurlan Kabdylkhak A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the History Department in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Eren Tasar Louise McReynolds Donald J. Raleigh © 2019 Nurlan Kabdylkhak ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Nurlan Kabdylkhak: Russian Empire-Building and the Kazakh Kinship System: The Chala- Qazaqs of the Kazakh steppe (under the direction of Eren Tasar) This thesis examines the phenomenon of Chala-Qazaqs: groups of mixed ethnic origin who lived in the Kazakh steppe. Chala-Qazaqs, or “half-Kazakhs,” emerged as a result of the rigid kinship system and patrilineal succession adopted by the steppe nomads. Since Kazakhs inherited their tribal identities from their fathers, they placed the progeny of Kazakh mothers and non-Kazakh fathers in the hybrid category of Chala-Qazaqs. Chala-Qazaq could serve as a transitional status on the way to becoming “fully” Kazakh. This “Kazakhification” was evinced by their incorporation into Kazakh tribal genealogies. This paper reveals that this process stopped in the nineteenth century due to the transformation of the Kazakh kinship system and the emergence of Chala-Qazaqs as a distinct social category – two inter-related shifts connected to Russian imperial expansion. Chala-Qazaqs present a fascinating case that exposes ethnic processes in pre-colonial and colonial settings and demonstrate the agency of Muslims under the Russian rule. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................