Aljazeera on Youtube™: a Credible Source in the United States?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al Jazeera As Covered in the U.S. Embassy Cables Published by Wikileaks

Al Jazeera As Covered in the U.S. Embassy Cables Published by Wikileaks Compiled by Maximilian C. Forte To accompany the article titled, “Al Jazeera and U.S. Foreign Policy: What WikiLeaks’ U.S. Embassy Cables Reveal about U.S. Pressure and Propaganda” 2011-09-21 ZERO ANTHROPOLOGY http://openanthropology.org Cable Viewer Viewing cable 04MANAMA1387, MINISTER OF INFORMATION DISCUSSES AL JAZEERA AND If you are new to these pages, please read an introduction on the structure of a cable as well as how to discuss them with others. See also the FAQs Reference ID Created Released Classification Origin 04MANAMA1387 2004-09-08 14:27 2011-08-30 01:44 CONFIDENTIAL Embassy Manama This record is a partial extract of the original cable. The full text of the original cable is not available. C O N F I D E N T I A L MANAMA 001387 SIPDIS STATE FOR NEA/ARP, NEA/PPD E.O. 12958: DECL: 09/07/2014 TAGS: PREL KPAO OIIP KMPI BA SUBJECT: MINISTER OF INFORMATION DISCUSSES AL JAZEERA AND IRAQ Classified By: Ambassador William T. Monroe for Reasons 1.4 (b) and (d) ¶1. (C) Al Jazeera Satellite Channel and Iraq dominated the conversation during the Ambassador's Sept. 6 introductory call on Minister of Information Nabeel bin Yaqoob Al Hamer. Currently released so far... The Minister said that he had directed Bahrain Satellite 251287 / 251,287 Television to stop airing the videotapes on abductions and kidnappings in Iraq during news broadcasts because airing Articles them serves no good purpose. He mentioned that the GOB had also spoken to Al Jazeera Satellite Channel and Al Arabiyya Brazil about not airing the hostage videotapes. -

An Al-Jazeera Effect in the US? a Review of the Evidence

Review Article Global Media Journal 2017 ISSN 1550-7521 Vol.15 No.29:83 An Al-Jazeera Effect in the US? A Tal Samuel-Azran* Review of the Evidence Sammy Ofer School of Communications, The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, 1 Kanfe Nesharin Street, Herzliya 46150, Israel Abstract *Corresponding author: Tal Samuel-Azran Some scholars argue that following 9/11Al Jazeera has promoted an Arab perspective of events in the US by exporting its news materials to the US news market. The study examines the validity of the argument through a review of the [email protected] literature on the issue during three successive periods of US-Al Jazeera interactions: (a) Al Jazeera Arabic's re-presentation in US mainstream media following 9/11, Sammy Ofer School of Communications, specifically during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (b) Al Jazeera English television The Interdisciplinary Center (IDC) Herzliya, 1 Kanfe Nesharin Street, Herzliya 46150, channel’s attempts to enter the US market since 2006 and (c) the reception of Israel. Al Jazeera America in the US, where the paper also adds an original analysis of Al Jazeera America's Twitter followers profiles. Together, these analyses provides Tel: 972 9-952-7272 strong counterevidence to the argument that Al-Jazeera was able to promote an Arab perspective of events in the US as the US administration, media and public resisted its entry to the US market. Citation: Samuel-Azran T. An Al-Jazeera Keywords: Al Jazeera; Qatar; Counter-public; Intercultural communication; United Effect in the US? A Review of the States; Twitter Evidence. -

EXCERPTS: Media Coverage About Al Jazeera English

EXCERPTS: Media Coverage about Al Jazeera English www.aljazeera.net/english January, 2009 www.livestation.com/aje (free live streaming) The Financial Times: "Al-Jazeera becomes the face of the frontline" Associated Press: “Al Jazeera drew U.S. viewers on Web during Gaza War” The Economist: “The War and the Media” U.S. News & World Report/ Jordan Times: “One of Gaza War’s big winners: Al Jazeera” International Herald Tribune/New York Times: "AJE provides an inside look at Gaza`` The Guardian, U.K.: "Al Jazeera's crucial reporting role in Gaza" Arab Media and Society: “Gaza: Of Media Wars and Borderless Journalism” The Los Angeles Times: "GAZA STRIP: In praise of Al Jazeera" Kansas City Star: “A different take on Gaza” Columbia Journalism Review: "(Not) Getting Into Gaza" Le Monde, Paris: "Ayman Mohyeldin, War Correspondent in Gaza" Halifax Chronicle Herald, Canada: "Why can't Canadians watch Al Jazeera?" The Huffington Post: "Al Jazeera English Beats Israel's Ban with Exclusive Coverage" Haaretz, Israel: "My hero of the Gaza war" The National, Abu Dhabi: "The war that made Al Jazeera English ‘different’’ New America Media: “Al Jazeera Breaks the Israeli Media Blockade" Israeli Embassy, Ottawa: “How I learned to Love Al Jazeera” 1 The Financial Times Al-Jazeera becomes the face of the frontline …With Israel banning foreign journalists from entering Gaza, al-Jazeera, the Qatari state-owned channel, has laid claim to being the only international broadcast house inside the strip. It has a team working for its Arab language network, which made its name with its reporting from conflict zones such as Iraq and Afghanistan. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

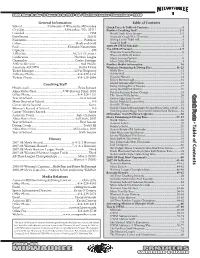

2008-09 Media Guide

UUWMWM Men:Men: BBrokeroke 1010 RecordsRecords iinn 22007-08007-08 / HHorizonorizon LeagueLeague ChampionsChampions • 20002000 1 General Information Table of Contents School ..................................University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Quick Facts & Table of Contents ............................................1 City/Zip ......................................................Milwaukee, Wis. 53211 Panther Coaching Staff ........................................................2-5 Founded ...................................................................................... 1885 Head Coach Erica Janssen ........................................................2-3 Enrollment ............................................................................... 28,042 Assistant Coach Kyle Clements ..................................................4 Nickname ............................................................................. Panthers Diving Coach Todd Hill ................................................................4 Colors ....................................................................... Black and Gold Support Staff ...................................................................................5 Pool .................................................................Klotsche Natatorium 2008-09 UWM Schedule ..........................................................5 Capacity..........................................................................................400 Th e 2008-09 Season ..............................................................6-9 -

Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq

'The Best Covered War in History': Intimate Perspectives from the Battlefields of Iraq by Andrew J. McLaughlin A thesis presented to the University Of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2017 © Andrew J. McLaughlin 2017 Examining Committee Membership The following served on the Examining Committee for this thesis. The decision of the Examining Committee is by majority vote. External Examiner Marco Rimanelli Professor, St. Leo University Supervisor(s) Andrew Hunt Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Jasmin Habib Associate Professor, University of Waterloo Internal Member Roger Sarty Professor, Wilfrid Laurier University Internal-external Member Brian Orend Professor, University of Waterloo ii Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. iii Abstract This study examines combat operations from the 2003 invasion of Iraq War from the “ground up.” It utilizes unique first-person accounts that offer insights into the realities of modern warfare which include effects on soldiers, the local population, and journalists who were tasked with reporting on the action. It affirms the value of media embedding to the historian, as hundreds of journalists witnessed major combat operations firsthand. This line of argument stands in stark contrast to other academic assessments of the embedding program, which have criticized it by claiming media bias and military censorship. Here, an examination of the cultural and social dynamics of an army at war provides agency to soldiers, combat reporters, and innocent civilians caught in the crossfire. -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

The V-Chip and the Constitutionality of Television Ratings

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 8 Volume VIII Number 2 Volume VIII Book 2 Article 1 1997 The V-Chip and the Constitutionality of Television Ratings Benjamin C. Zipursky Eric Burns Donald W. Hawthorne Thomas Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Benjamin C. Zipursky, Eric Burns, Donald W. Hawthorne, and Thomas Johnson, The V-Chip and the Constitutionality of Television Ratings, 8 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 301 (1997). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol8/iss2/1 This Transcript is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL1.TYP 9/29/2006 4:44 PM Panel 1: The V-Chip and the Constitutionality of Television Ratings Moderator: Benjamin C. Zipursky* Participants: Eric Burns** Donald W. Hawthorne, Esq.*** Thomas Johnson**** David H. Moulton, Esq.***** Robert W. Peters, Esq.****** MR. ZIPURSKY: Welcome to the Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal’s Sixth Annual Symposium on the First Amendment and the Media. I am Profes- sor Benjamin Zipursky of Fordham University School of Law. Out first panel discussion covers one of the hot topics in both the television industry and the legal profession, the V-chip and the constitutionality of the associated television ratings that will be re- quired to make the chip work properly. -

Asper Nation Other Books by Marc Edge

Asper Nation other books by marc edge Pacific Press: The Unauthorized Story of Vancouver’s Newspaper Monopoly Red Line, Blue Line, Bottom Line: How Push Came to Shove Between the National Hockey League and Its Players ASPER NATION Canada’s Most Dangerous Media Company Marc Edge NEW STAR BOOKS VANCOUVER 2007 new star books ltd. 107 — 3477 Commercial Street | Vancouver, bc v5n 4e8 | canada 1574 Gulf Rd., #1517 | Point Roberts, wa 98281 | usa www.NewStarBooks.com | [email protected] Copyright Marc Edge 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (access Copyright). Publication of this work is made possible by the support of the Canada Council, the Government of Canada through the Department of Cana- dian Heritage Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Printing, Cap-St-Ignace, QC First printing, October 2007 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Edge, Marc, 1954– Asper nation : Canada’s most dangerous media company / Marc Edge. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55420-032-0 1. CanWest Global Communications Corp. — History. 2. Asper, I.H., 1932–2003. I. Title. hd2810.12.c378d34 2007 384.5506'571 c2007–903983–9 For the Clarks – Lynda, Al, Laura, Spencer, and Chloe – and especially their hot tub, without which this book could never have been written. -

Journalism Ethics and Standards - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 2/27/12 19:58 Journalism Ethics and Standards from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Journalism ethics and standards - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 2/27/12 19:58 Journalism ethics and standards From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Journalism ethics and standards comprise principles of ethics and of good practice as applicable to the specific challenges faced by journalists. Historically and currently, this subset of media ethics is widely known to journalists as their professional "code of ethics" or the "canons of journalism".[1] The basic codes and canons commonly appear in statements drafted by both professional journalism associations and individual print, broadcast, and online news organizations. “ Every news organization has only its credibility and reputation to rely on. ” —Tony Burman, ex-editor-in-chief of CBC News, The Globe and Mail, October 2001[2] While various existing codes have some differences, most share common elements including the principles of — truthfulness, accuracy, objectivity, impartiality, fairness and public accountability — as these apply to the acquisition of newsworthy information and its subsequent dissemination to the public.[3][4][5][6] Like many broader ethical systems, journalism ethics include the principle of "limitation of harm." This often involves the withholding of certain details from reports such as the names of minor children, crime victims' names or information not materially related to particular news reports release of which might, for example, harm someone's reputation.[7][8] Some journalistic Codes of Ethics, notably the European ones,[9] also include a concern with -

High School Renovation Again on Ballot; Write-In Vier Joins Declared Board Hopefuls by R

RAHWAY "f. N.J. 07065 J" New Jersey's Oldest Weekly JS tyspaper-Established 1822 VOL. 161 NO. 14 RAHWAY, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, APRIL 7, 1983 USPS454I60 20 CENTS High School renovation again on ballot; write-in vier joins declared Board hopefuls By R. R. Faszczewski gymnasium itself, which cond time. cement and $55,000 for The Rahway News-Record. candidate in an election in the Roosevert School Par- dition to being the Board ver Cleveland School at E. In addition to voting would nearly double the They argue repairs can be landscaping. The present ^ice presi- which there were no declar- ent-Teacher Assn. and a liaison to the junior high Milton Ave., in the School again on a proposed size of the present gym- done a little at a time so tax- Although there are only dent of the Schob! Board, ed candidates for the un- member of the Rahway $5,990,000 bond-issue re- school. • -•,.,./ Distrist for the legal voters nasium. payers will not have to foot three declared candidates Mrs. Elizabeth If Jacobs of expired term. Parent-Teacher Assn./Or- She is a part-time student residing within General El- ferendum tor renovations to Supporters of the bond the bill all at once. Among running for the three Board 318 Russell Am, won the The administrative assis- ganization Presidents' Rahway High School and in the Urban Studies Pro- ection District Nos. 1 and 2 issue argue the facilities items which opponents seats, at least one write-in right to serve <$t the re- tant to Dr. -

A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage

University of Miami Law Review Volume 61 Number 3 Volume 61 Number 3 (April 2007) SYMPOSIUM The Schiavo Case: Article 4 Interdisciplinary Perspectives 4-1-2007 A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage Lili Levi University of Miami School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Part of the Family Law Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, and the Medical Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Lili Levi, A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage, 61 U. Miami L. Rev. 665 (2007) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol61/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A New Model for Media Criticism: Lessons from the Schiavo Coverage LILI LEVI* I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................... 665 II. SHARPLY DIVIDED CRITICISM OF SCHIAVO MEDIA COVERAGE ................... 666 . III. How SHOULD WE ASSESS MEDIA COVERAGE? 674 A. JournalisticStandards ............................................ 674 B. Internal Limits of JournalisticStandards ............................. 677 C. Modern Pressures on Journalistic Standards and Editorial Judgment .... 680 1. CHANGES IN INDUSTRY STRUCTURE AND RESULTING ECONOMIC PRESSURES ................................................... 681 2. THE TWENTY-FOUR HOUR NEWS CYCLE ................................. 686 3. BLURRING THE DISTINCTION BETWEEN NEWS, OPINION, AND ENTERTAINMENT .............................................. 688 4. THE RISE OF BLOGS AND NEWS/COMMENTARY WEB SITES ................. 690 5. "NEWS AS CATFIGHT" - CHANGING DEFINITIONS OF BALANCE ...........