The Oilpatch Packs Its Bags

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

P:\HANADMIN\BOUND\Committees\27Th Legislature\2Nd Session 2009\HS Members-Presenter Pages for BV\HS Cover 100127.Wpd

Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Second Session Standing Committee on the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund Wednesday, January 27, 2010 2 p.m. Transcript No. 27-2-6 Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Second Session Standing Committee on the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund Forsyth, Heather, Calgary-Fish Creek (WA), Chair Elniski, Doug, Edmonton-Calder (PC), Deputy Chair Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC) DeLong, Alana, Calgary-Bow (PC) Denis, Jonathan, Calgary-Egmont (PC) Johnston, Art, Calgary-Hays (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Sandhu, Peter, Edmonton-Manning (PC)* * substitution for Jonathan Denis Department of Finance and Enterprise Participants Hon. Ted Morton Minister Rod Babineau Manager, Portfolio Analysis Aaron Brown Director, Portfolio Management Rod Matheson Assistant Deputy Minister, Treasury and Risk Management Tim Wiles Deputy Minister Alberta Investment Management Corporation Participants Leo de Bever Chief Investment Officer Douglas Stratton Director, Fund Management Group Auditor General’s Office Participants Fred Dunn Auditor General Merwan Saher Assistant Auditor General, Audit Division Betty LaFave Principal Support Staff W.J. David McNeil Clerk Louise J. Kamuchik Clerk Assistant/Director of House Services Micheline S. Gravel Clerk of Journals/Table Research Robert H. Reynolds, QC Senior Parliamentary Counsel Shannon Dean Senior Parliamentary Counsel Corinne Dacyshyn Committee Clerk Erin Norton Committee Clerk Jody Rempel Committee Clerk Karen Sawchuk Committee Clerk Rhonda Sorensen Manager of Communications Services Melanie Friesacher Communications Consultant Tracey Sales Communications Consultant Philip Massolin Committee Research Co-ordinator Stephanie LeBlanc Legal Research Officer Diana Staley Research Officer Rachel Stein Research Officer Liz Sim Managing Editor of Alberta Hansard Transcript produced by Alberta Hansard January 27, 2010 Heritage Savings Trust Fund HS-85 2 p.m. -

THE AMERICAN IMPRINT on ALBERTA POLITICS Nelson Wiseman University of Toronto

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 2011 THE AMERICAN IMPRINT ON ALBERTA POLITICS Nelson Wiseman University of Toronto Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Wiseman, Nelson, "THE AMERICAN IMPRINT ON ALBERTA POLITICS" (2011). Great Plains Quarterly. 2657. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/2657 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE AMERICAN IMPRINT ON ALBERTA POLITICS NELSON WISEMAN Characteristics assigned to America's clas the liberal society in Tocqueville's Democracy sical liberal ideology-rugged individualism, in America: high status was accorded the self market capitalism, egalitarianism in the sense made man, laissez-faire defined the economic of equality of opportunity, and fierce hostility order, and a multiplicity of religious sects com toward centralized federalism and socialism peted in the market for salvation.l Secondary are particularly appropriate for fathoming sources hint at this thesis in their reading of Alberta's political culture. In this article, I the papers of organizations such as the United contend that Alberta's early American settlers Farmers of Alberta (UFA) and Alberta's were pivotal in shaping Alberta's political cul Social Credit Party.2 This article teases out its ture and that Albertans have demonstrated a hypothesis from such secondary sources and particular affinity for American political ideas covers new ground in linking the influence and movements. -

On First Nations Consultation

The Government of Alberta’s Volume 4, Issue 1 – January 2007 Fast Facts on First Nations Consultation A “MADE IN ALBERTA” APPROACH Applying Traditional Use Data: First Nations A Case Study Consultation Guidelines The following is an excerpt of a Alberta and industry to work conversation with Mr. Laren Bill, together in resolving land use The Government of Alberta’s First Nations Consultation Aboriginal Consultation Officer with conflicts. Guidelines on Land Management and Resource Alberta Tourism, Parks, Recreation Can you provide an example of Development were released on September 1, 2006. and Culture (TPRC) – formally a First Nation that is sharing The guidelines are consistent with the May 16, 2005 known as Alberta Community traditional use data with your consultation policy and will guide First Nations Development. Laren has been department and explain why consultation on land management and resource working closely with the O’Chiese they have chosen to share that development in relation to activities such as First Nation on their Traditional information? exploration, resource extraction, and management Use Study (TUS). of forests, fish and wildlife. Laren: The O’Chiese First Nation Interviewer: First of all, can you has shared some traditional use Since the release of the guidelines, over 500 people give a brief update on the site data with our department attended one of several information sessions hosted traditional use study initiative to work together to protect their across Alberta. The information sessions gave First in Alberta? Nations and industry representatives the opportunity culturally significant sites. Their to ask questions and express concerns about the Laren: There are 32 traditional use data will act as a trigger for new guidelines. -

Orange Chinook: Politics in the New Alberta

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2019-01 Orange Chinook: Politics in the New Alberta University of Calgary Press Bratt, D., Brownsey, K., Sutherland, R., & Taras, D. (2019). Orange Chinook: Politics in the New Alberta. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109864 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca ORANGE CHINOOK: Politics in the New Alberta Edited by Duane Bratt, Keith Brownsey, Richard Sutherland, and David Taras ISBN 978-1-77385-026-9 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

Leadership Selection in Alberta, 1992-2011: a Personal Perspective

Leadership Selection in Alberta, 1992-2011: A Personal Perspective Ted Morton In 1991, the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta changed its rules for selecting its party leader. They abandoned their traditional method of a leadership convention (with delegates drawn from each constituency), and instituted a new one-member, one-vote system. Under this new system, the Alberta PCs have elected three new party leaders: Ralph Klein in 1992; Ed Stelmach in 2006; and Alison Redford in 2011. In each of these leadership contests the winner 2013 CanLIIDocs 380 immediately became the Premier of Alberta. This article looks at the impact of the new selection procedure for politics in Alberta. he 1991 leadership reforms can best be described Initially the Party was quite proud of its new as creating what the Americans call an “open democratic credentials.4 But as these rules were put Tprimary.” Not only is it based on the one- into play in three leadership contests over the next two member, one-vote principle, but the membership decades, they have had significant and unintended requirement is essentially “open”. That is, there are no consequences. I have tried to summarize these in the pre-requisites such as prior party membership or cut- following six propositions: off dates for purchasing a membership. Memberships can be bought at the door of the polling station on the day of the vote for $5. The system allows for two rounds • The rules favour “outsider” candidates over candidates supported by the Party Establishment. of voting. If no candidate receives an absolute majority 1 • The rules create an incentive for the Second and (50% +1) on the first voting-day, then the top three go Third Place candidates to ally themselves against 2 on to a second vote one week later. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 86 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................96 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................94 Total number of seats ................79 Surrey-Panorama Ridge..........................Jagrup Brar..........................................95 Liberal..........................................46 Surrey-Tynehead.....................................Dave S. Hayer.....................................96 New Democratic Party ...............33 Surrey-Whalley.......................................Bruce Ralston......................................98 Abbotsford-Clayburn..............................John van Dongen ................................99 Surrey-White Rock .................................Gordon Hogg ......................................96 Abbotsford-Mount Lehman....................Michael de Jong..................................96 Vancouver-Burrard.................................Lorne Mayencourt ..............................98 Alberni-Qualicum...................................Scott Fraser .........................................96 Vancouver-Fairview ...............................Gregor Robertson................................98 Bulkley Valley-Stikine ...........................Dennis -

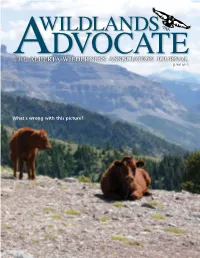

What's Wrong with This Picture?

JUNE 2015 What’s wrong with this picture? Editor: CONTENTS Ian Urquhart JUNE 2015 • VOL. 23, NO. 3 Graphic Design: Doug Wournell B Des, ANSCAD Printing: Features Association News Colour printing and process by Topline Printing 4 The Sky Shouldn’t Be The Limit: 24 Anna Caddel… Winner of AWA’s Cattle in the Castle Calgary Youth Science Fair Award 7 Ranchers and Wolves: A Better Way 25 AWA Kids’ Camp Preview 11 The Inside Scoop: Looking Back at 26 Another Tremendous Success: the 2014 Martha Kostuch Lecture AWA’s 24th Annual Climb and Run For Wilderness 14 An Ecologist’s Optimism On the Proposed Introduction of Bison to Wilderness Watch Banff National Park 16 Lessons from the Crowsnest Pass 28 Updates BearSmart Program Departments ALBERTA WILDERNESS 19 Between the lines: Grizzly Recovery ASSOCIATION 20 Former Senior Parks Canada 30 Reader’s Corner “Defending Wild Alberta through Officials Speak Out Against Lake Awareness and Action” Louise Ski Area Expansion Events Alberta Wilderness Association is a charitable non-government Thinking Mountains: 22 organization dedicated to the An Interdisciplinary Initiative Summer Events 31 completion of a protected areas donation, call 403-283-2025 or Cover Photo contribute online at AlbertaWilderness.ca. No, the cover photo isn’t a product of Photoshop. Jim Wild Lands Advocate is published bi- monthly, 6 times a year, by Alberta Lucas took this photo of cows Wilderness Association. The opinions resting during their ascent expressed by the authors in this of Whistle Mountain in the publication are not necessarily those South Castle Valley. Windsor of AWA. The editor reserves the right Ridge and Castle Mt. -

Provincial Legislatures

PROVINCIAL LEGISLATURES ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL LEGISLATORS ◆ PROVINCIAL & TERRITORIAL MINISTRIES ◆ COMPLETE CONTACT NUMBERS & ADDRESSES Completely updated with latest cabinet changes! 88 / PROVINCIAL RIDINGS PROVINCIAL RIDINGS British Columbia Saanich South .........................................Lana Popham ....................................100 Shuswap..................................................George Abbott ....................................95 Total number of seats ................85 Skeena.....................................................Robin Austin.......................................95 Liberal..........................................49 Stikine.....................................................Doug Donaldson .................................97 New Democratic Party ...............35 Surrey-Cloverdale...................................Kevin Falcon.......................................97 Independent ................................1 Surrey-Fleetwood ...................................Jaqrup Brar..........................................96 Surrey-Green Timbers ............................Sue Hammell ......................................97 Abbotsford South....................................John van Dongen ..............................101 Surrey-Newton........................................Harry Bains.........................................95 Abbotsford West.....................................Michael de Jong..................................97 Surrey-Panorama ....................................Stephanie Cadieux -

Ministerial Forum Toolkit

October 9, 2009 Ministerial Forum Toolkit The AAMDC has introduced a new toolkit for members to use at the Fall 2009 Convention. Our Ministerial Forum Toolkit includes minister information, portfolios and current issues for each provincial ministry. We believe members will find this toolkit useful when formulating questions to pose at the ministerial forum or to understand which departments have a hand in matters of significance to rural municipalities. The Ministerial Forum Toolkit is attached to this bulletin in PDF form. It is also available online here. Enquiries may be directed to: Candice Van Beers Kim Heyman Administrative & Convention Coordinator Director of Advocacy & Communications (780) 955.4095 (780) 955.4079 Attachment ministerial forum toolkit Aboriginal Affairs Portfolio Current Issues Hon. Gene Zwozdesky • Aboriginal Relations • Duty to consult • Métis Settlements Appeals Tribunal • Traditional-use Studies • Métis Settlements Ombudsman • First Nations Development Fund Advanced Education Portfolio Current Issues Hon. Doug Horner • Apprenticeship and Industry Training • Veterinary program at University • Adult Learning of Calgary • Technology • Mount Royal College in Calgary to become Mount Royal University Agriculture & Rural Portfolio Current Issues Development Hon. George Groeneveld • Encourages industry growth • Rural Connectivity Gap Analysis • Rural and environmental sustainability: • Land-use Framework soil conservation, water quality, range • Agriculture Equipment Policy management, climate change, • Roadside Forage -

Alberta Hansard

Province of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fifth Session Alberta Hansard Tuesday, February 7, 2012 Issue 1 The Honourable Kenneth R. Kowalski, Speaker Legislative Assembly of Alberta The 27th Legislature Fifth Session Kowalski, Hon. Ken, Barrhead-Morinville-Westlock, Speaker Cao, Wayne C.N., Calgary-Fort, Deputy Speaker and Chair of Committees Zwozdesky, Gene, Edmonton-Mill Creek, Deputy Chair of Committees Ady, Cindy, Calgary-Shaw (PC) Kang, Darshan S., Calgary-McCall (AL), Allred, Ken, St. Albert (PC) Official Opposition Whip Amery, Moe, Calgary-East (PC) Klimchuk, Hon. Heather, Edmonton-Glenora (PC) Anderson, Rob, Airdrie-Chestermere (W), Knight, Mel, Grande Prairie-Smoky (PC) Wildrose Opposition House Leader Leskiw, Genia, Bonnyville-Cold Lake (PC) Benito, Carl, Edmonton-Mill Woods (PC) Liepert, Hon. Ron, Calgary-West (PC) Berger, Hon. Evan, Livingstone-Macleod (PC) Lindsay, Fred, Stony Plain (PC) Bhardwaj, Naresh, Edmonton-Ellerslie (PC) Lukaszuk, Hon. Thomas A., Edmonton-Castle Downs (PC) Bhullar, Hon. Manmeet Singh, Calgary-Montrose (PC) Lund, Ty, Rocky Mountain House (PC) Blackett, Lindsay, Calgary-North West (PC) MacDonald, Hugh, Edmonton-Gold Bar (AL) Blakeman, Laurie, Edmonton-Centre (AL), Marz, Richard, Olds-Didsbury-Three Hills (PC) Official Opposition Deputy Leader, Mason, Brian, Edmonton-Highlands-Norwood (ND), Official Opposition House Leader Leader of the ND Opposition Boutilier, Guy C., Fort McMurray-Wood Buffalo (W) McFarland, Barry, Little Bow (PC) Brown, Dr. Neil, QC, Calgary-Nose Hill (PC) McQueen, Hon. Diana, Drayton Valley-Calmar (PC) Calahasen, Pearl, Lesser Slave Lake (PC) Mitzel, Len, Cypress-Medicine Hat (PC) Campbell, Robin, West Yellowhead (PC), Morton, Hon. F.L., Foothills-Rocky View (PC) Government Whip Notley, Rachel, Edmonton-Strathcona (ND), Chase, Harry B., Calgary-Varsity (AL) ND Opposition House Leader Dallas, Hon. -

Being Métis in Canada: an Unsettled Identity

BEING MÉTIS IN CANADA: AN UNSETTLED IDENTITY A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities. 2017 SINÉAD O’SULLIVAN SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................................ 2 Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................ 4 List of Images ...................................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... 6 Declaration .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Copyright Statement ........................................................................................................................... 7 Dedication ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................................