2020 Analysis of Impediments, City of Toledo Prepared by the Fair Housing Center 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Athlete, January 1990 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 1-1-1990 The Athlete, January 1990 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Athlete, January 1990" (1990). The Athlete. Book 356. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/356 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January, 1990 7^\ •V* Volume L, No. 6 .\ n"* >. ^k^ ^^J t V % % Official Publication of The Kentucky High School aft*~— Athletic Association Member of National Federation of Stale High School Associalions VIEWPOINTS At What Cost Is Victory In Athletics? by Jim Watkins Win — pressure; victory — pressure; choose — pressure; practice, practice, practice — pressure. Sound familiar? These are the words and ideas that we are preaching to our high school athletes. Today, high school sports are BIG dollar productions. Victory and winning teams mean dollars for the athletic department, new uniforms, travel, prestige for community. But where are we going with our athletes and their values? What type of future do we see for tomorrow's players'? What have we done to the play for the love-of-the-game attitude? Have we changed to a play-for-the-dollar attitude'' Years ago, many young men and women played athletics for the pleasure and the thrill. It was fun, exciting and for some a little glamour. -

Toledo Public Schools Directory

Toledo Public Schools Directory The Toledo Board of Education is committed to equal educational and employment opportunities in all of its decisions, programs, and activities. Toledo Public Schools district will not discriminate against any student of the district on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, national origin or handicap. The Board of Education is pledged to provide equal employment opportunities to all persons without regard to race, color, religion, sex, age, handicapping condition, or national origin. The district complies with the nondiscrimination requirements of Titles VI, IX and Sec. 504. Thursday, September 9, 2021 Page 1 of 130 Toledo Public Schools Directory Board of Education Board Members Office Board Members Office Phone 419-671-0550 Fax 419-671-0082 1609 N. Summit St. Toledo, OH 43604 Name Job Title Email Address Direct Phone Direct Fax Christine Varwig President [email protected] Polly Gerken Vice President [email protected] Sheena Barnes Board Member [email protected] Stephanie Eichenberg Board Member [email protected] Bob Vasquez Board Member [email protected] Thursday, September 9, 2021 Page 2 of 130 Toledo Public Schools Directory Administration Administration Building Administration Building Phone 419-671-0001 Fax 1609 N. Summit St. Toledo, OH 43604 Name Job Title Email Address Direct Phone Direct Fax Romules Durant Superintendent [email protected] 419-671-0500 Angela Jordan Executive Assistant to the Superintendent [email protected] 419-671-0500 Theresa Cummings Secretary to the Superintendents Office [email protected] -

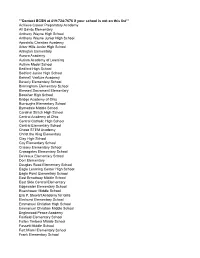

Contact BCSN at 419-724-7676 If Your School Is Not on This List** Achieve

**Contact BCSN at 419-724-7676 if your school is not on this list** Achieve Career Preparatory Academy All Saints Elementary Anthony Wayne High School Anthony Wayne Junior High School Apostolic Christian Academy Arbor Hills Junior High School Arlington Elementary Aurora Academy Autism Academy of Learning Autism Model School Bedford High School Bedford Junior High School Bennett Venture Academy Beverly Elementary School Birmingham Elementary School Blessed Sacrament Elementary Bowsher High School Bridge Academy of Ohio Burroughs Elementary School Byrnedale Middle School Cardinal Stritch High School Central Academy of Ohio Central Catholic High School Central Elementary School Chase STEM Academy Christ the King Elementary Clay High School Coy Elementary School Crissey Elementary School Crossgates Elementary School DeVeaux Elementary School Dorr Elementary Douglas Road Elementary School Eagle Learning Center High School Eagle Point Elementary School East Broadway Middle School East Side Central Elementary Edgewater Elementary School Eisenhower Middle School Ella P. Stewart Academy for Girls Elmhurst Elementary School Emmanuel Christian High School Emmanuel Christian Middle School Englewood Peace Academy Fairfield Elementary School Fallen Timbers Middle School Fassett Middle School Fort Miami Elementary School Frank Elementary School Ft. Meigs Elementary School Garfield Elementary School Gateway Middle School George A. Phillips Academy Gesu Elementary Glass City Academy Glendale-Feilbach Elementary School Glenwood Elementary School Glenwood -

HISTORY of District 7

District 7 Basketball Coaches Association T _ÉÉ~ tà à{x ctáà …a Little History of the Coaches, Players, and Teams -District 7 Past Presidents -District 7 Scholarship Winners -District 7 Players of the Year -District 7 Coaches of the Year -District 7 Hall of Fame Inductees -OHSBCA Hall of Fame Inductees -District 7 Retired Coach Recipients -State Players and Coaches of the Year -North/South and Ohio/Indiana All Star Participants -State Tournament Qualifying Teams and Results Northwest Ohio District Seven Coaches Association Past Presidents Dave Boyce Perrysburg Gerald Sigler Northview Bud Felhaber Clay Bruce Smith Whitmer Betty Jo Hansbarger Swanton Tim Smith Northview Marc Jump Southview Paul Wayne Holgate Dave Krauss Patrick Henry Dave McWhinnie Toledo Christian Kirk Lehman Tinora Denny Shoemaker Northview Northwest Ohio District Seven Coaches Association Scholarship Winners Kim Asmus Otsego 1995 Jason Bates Rogers 1995 Chris Burgei Wauseon 1995 Collin Schlosser Holgate 1995 Kelly Burgei Wauseon 1998 Amy Perkins Woodmore 1999 Tyler Schlosser Holgate 1999 Tim Krauss Archbold 2000 Greg Asmus Otsego 2000 Tyler Meyer Patrick Henry 2001 Brock Bergman Fairview 2001 Ashley Perkins Woodmore 2002 Courtney Welch Wayne Trace 2002 Danielle Reynolds Elmwood 2002 Brett Wesche Napoleon 2002 Andrew Hemminger Oak Harbor 2003 Nicole Meyer Patrick Henry 2003 Erica Riblet Ayersville 2003 Kate Achter Clay 2004 Michael Graffin Bowling Green 2004 Trent Meyer Patrick Henry 2004 Cody Shoemaker Northview 2004 Nathan Headley Hicksville 2005 Ted Heintschel St. -

Scott Hall of Fame

Volume 38, No. 4 “And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” March 30, 2016 Scott Hall of Fame Back row -Carrington Thomas, Michelle Hollie. Front row- Dennis Black ‘74, honoree Trevor Black ‘74, and Ristina Thompson In This Issue... The Soulcial Scene ODP A Women’s Pretty Brown Girls Business Etiquette Page 16 Classifieds History Page 8 Page 10 Tolliver Page 15 Month Scott HS Page 2 Fros and Fashions Tribute A Community Dinner Hall of Fame Page 12 Pages 3-7 Page 9 Page 16 Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth March 30, 2016 Once Upon A Time... By Lafe Tolliver, Esq Guest Column Once upon a time and far away in a land called America there lived a These white Republicans and their friends just got madder and madder nation of people called Americans. They had a nice big land and thought at these other people who were always voting Democratic and trying to they had fair laws and tried to treat everybody fairly and equally … ex- make everyone equal under the law. cept for black people. One day, a man who grew orange hair and made a lot of money buying They did not like black people because they feared anyone who was not and selling real estate and conducting a reality game on TV was sitting in white or near white like them. They were told by some hateful people that his lavish high-rise tower penthouse. black meant evil and bad and they chose to believe it and so they did. He was bored and wanted to be somebody and have everyone look up to They first took black people by force from a place called Africa and him so he thought that he would run to become the president of the USA put them in chains to work for them for hundreds of years, for free. -

BCSN Scholar Spotlight Scholarship 2021-2022 Program Information Sheet

BCSN Scholar Spotlight Scholarship 2021-2022 Program Information Sheet The BCSN Scholar Spotlight Scholarship was established to recognize the achievements of graduating high school seniors residing in the Buckeye Broadband service area pursuing a degree at an accredited post-secondary institution. Scholarships can be used toward tuition, on-campus room & board, books and fees. APPLICATION DEADLINES NUMBER OF AWARDS AWARD AMOUNTS September 24, 2021 7 one-time, non-renewable awards $1,000 (one-time) December 3, 2021 1 renewable award (up to 4 years) $2,500 (renewable) APPLICANT ELIGIBILITY 1. Must be a U.S. Citizen. 2. Must be a permanent resident of the Buckeye Broadband service area (see eligible zip codes list below). 3. Must be a high school senior graduating in spring of 2022 (see eligible schools list below). 4. Must have a minimum 3.0 cumulative GPA or higher. 5. Must be nominated by your high school guidance counselor. 6. Employees and dependents of employees of Buckeye Companies are not eligible to apply. SELECTION CRITERIA Greater Toledo Community Foundation may revise the criteria from year to year based on recommendations from the Scholarship Committee, Buckeye Broadband, and others. The Scholarship Committee reviews the eligible applications based on the following criteria in order of significance: 1. Scholastic Aptitude (Test Scores) 2. Academic Achievements 3. Financial Need (finalists will be required to complete a College Budget Form prior to the interview) 4. Individual Motivation, Ability & Potential 5. Extracurricular Activities 6. Community Service & Volunteer Involvement 7. Work Experience 8. College & Career Goals Essay 9. Recommendation Letters 10. Interview for 8 Scholar Scholastic Finalists ELIGIBLE ZIP CODES Applicants must reside in the Buckeye Broadband service area which consists of the following zip codes. -

Toledo Public Schools, Toledo, Ohio

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OFFICE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS, REGION XV 1350 EUCLID AVENUE, SUITE 325 REGION XV MICHIGAN CLEVELAND, OH 44115 OHIO January 20, 2016 Jennifer J. Dawson, Esq. Marshall & Melhorn, LLC Four Seagate, Eighth Floor Toledo, Ohio 43604 Re: Case No. 15-10-5002 Toledo Public Schools Dear Ms. Dawson: This is to advise you of the resolution of the above-referenced compliance review that was initiated by the U.S. Department of Education (Department), Office for Civil Rights (OCR), on September 28, 2010. This compliance review was undertaken to assess whether the Toledo Public Schools (the District or TPS) provides African American students with equal access to its resources, including strong teaching, leadership, and support, school facilities, technology and instructional materials, and educational programs. OCR initiated this compliance review under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (Title VI), as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000d et seq., and its implementing regulation at 34 C.F.R. Part 100, which prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in programs and activities receiving financial assistance from the Department. As a recipient of financial assistance from the Department, the District is subject to Title VI and, therefore, OCR had jurisdiction to conduct this compliance review. During the course of and prior the conclusion of OCR’s investigation, the District expressed an interest in voluntarily resolving the case and entered into a Resolution Agreement (the Agreement), which commits the District to specific actions to address issues identified during OCR’s review. This letter summarizes the applicable legal standards, the main areas of information gathered during the review, and how the review was resolved. -

Heather Konerman Honored As Outstanding Youth in Philanthropy Contentsvolume 30, ISSUE 3 | FALL 2017

VOLUME 30, ISSUE 3 HOLY CROSS FALL 2017 FOR ALUMNI, FAMILY AND FRIENDS OF HOLY CROSS DISTRICT HIGH SCHOOL Heather Konerman Honored as Outstanding Youth In Philanthropy contentsVOLUME 30, ISSUE 3 | FALL 2017 Holy Cross District High School 3617 Church Street Covington, KY 41015 859-431-1335 www.hchscov.com PASTORAL ADMINISTRATOR Rev. Thomas Robbins PRINCIPAL Mike Holtz DEAN OF STUDENTS Ken Shields, guest speaker at the Blessing of Benefactors Dinner and former head coach Pat Ryan of the Northern Kentucky University men’s basketball team, with Pat Ryan, long time ATHLETIC DIRECTOR teacher at Holy Cross and former assistant coach at NKU. Anne Julian CAMPUS MINISTER 4 BLESSING OF Terese Meeks BENEFACTORS DINNER DIRECTOR OF ADVANCEMENT Emma Trieger 5 ACADEMICS 9 SPORTS OUR MISSION 15 REMEMBER WHEN Holy Cross District High School provides a quality Catholic 16 REUNIONS education for all of its students through the deeply rooted 17 UPDATES commitment of the Holy Cross school community to education, 20 ANNUAL APPEAL diversity, family and religion. 22 IN MEMORIAM FROM THE principal DEAR ALUMNI, PARENTS AND FRIENDS, As a Holy Cross tradition, we opened the school year with our blessing ceremony, where we introduced our theme for the year – “Be Kind, Be Humble.” It is a constant reminder to put feet to our faith. The entire faculty proudly wore “Be Kind, Be Humble” shirts in unison with the students as a sign of our commitment with them in this challenge we face together. I was able to be a part of this call to action by putting feet to my faith when I joined our junior class on their day of service. -

The Athlete, January 1987 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 1-1-1987 The Athlete, January 1987 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Athlete, January 1987" (1987). The Athlete. Book 326. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/326 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • » % January, 1987 Volume XLIX No. 6 r _ :<. f N . r i u ft-:4 1? Official Publication of Thei n Kentucky High School Athletic Association Member Of National Federation of State High School Associations I CHEMICAL HEALTH © ^IargeT National Federation survey indicates schools favor drug education, prevention An overwhelming maionty of high current drug-testing program About state or national program. Some also schools surveyed by the National five percent did not respond, and indicated implementation of a Federation are not involved in drug approximately one percent (15 drug testing program would depend on testing and favor prevention and schools) have drug-testing programs the community education programs to solve the drug Fifty-five percent of the respondents Other reasons listed for not and alcohol problems of the nation's were not in favor of any type of implementing a drug-testing -

Boone County School District (PDF)

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REGION III DELAWARE OFFICE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS KENTUCKY MARYLAND PENNSYLVANIA THE WANAMAKER BUILDING, SUITE 515 WEST VIRGINIA 100 PENN SQUARE EAST PHILADELPHIA, PA 19107-3323 March 17, 2021 IN RESPONSE, PLEASE REFER TO 03201278 Lisa D. Beck, Ed.D. Boone County Schools Interim Superintendent of Schools 69 Ave B Madison, WV 25130 By Email Only: [email protected] Dear Superintendent Beck: This is to notify you of the resolution of the above-referenced complaint filed with the U.S. Department of Education (Department), Office for Civil Rights (OCR), against Boone County Schools (the District). The complaint alleges that the District discriminates on the basis of sex in its interscholastic sports at Van Junior/Senior High School (the School) in its provision of locker rooms, practice, and competitive facilities. OCR enforces Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Title IX) and its implementing regulation at 34 C.F.R. Part 106, which prohibit discrimination on the basis of sex in any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance from the Department. Because the District receives Federal financial assistance from the Department, OCR has jurisdiction over it pursuant to Title IX. To date, OCR has investigated this complaint by reviewing information provided by the Complainant and District, including interviews with District personnel. Prior to the completion of OCR’s investigation, on February 17, 2021, the District requested to resolve the complaint. On February 26, 2021, the Complainant withdrew a previous allegation regarding the facilities at Scott High School. Dismissal of Allegation Concerning School 2 Pursuant to OCR’s case processing procedures, we may dismiss an allegation when a complainant withdraws the allegation. -

Aurora House Project

Volume 42, No. 8 “And Ye Shall Know The Truth...” January 11, 2017 Aurora House Project NANBPWC Members Present Holiday Gifts to Aurora House Education Section In This Issue... In Memoriam Classifieds Northwest State Ava DuVernay JT Wiiliamson Page 15 Perryman Sykes on Community at Lourdes Page 12 Cover Story: Page 2 MLK and College Page 9 Christ Page 6 Book NANBPWC Children Page 4 Mid Year School Review and Aurora College Services Foster Challenges Page 13 House Scholarships Care and State MLK Page 10 Page 16 Adoption Awards Page 7 BlackMarket- Place Training Page 5 Toledo Ballet Zoo Events Page 3 Page 8 Page 11 Page 14 Page 2 The Sojourner’s Truth January 11, 2017 Who’s On First? By Rev. Donald L. Perryman, D.Min. The Truth Contributor If it wasn’t for baseball, I’d be in either the penitentiary or the cemetery. - Babe Ruth “They must not like each other,” whispered Wanda Butts, daughter of storied former little league baseball coach John Butts, who piloted Toledo’s young, all black Lincoln School Tigers in the late 1950s and early 60s. Toledo City Council Recreation Committee Chairman Cecelia Adams, PhD, was being bombarded with one verbal brush-back pitch after an- other, apparently designed to intimidate and send a clear message. In an age of rising youth violence and absence of participation in positive summer recreational activities, Adams was advocating for the City’s participation in a Little League sanctioned Tee-Ball program for the central city. The program would replace a pipeline to prison or gang membership with teamwork, skills development and a conduit for high- er levels of youth baseball. -

The Athlete, April 1991 Kentucky High School Athletic Association

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass The Athlete Kentucky High School Athletic Association 4-1-1991 The Athlete, April 1991 Kentucky High School Athletic Association Follow this and additional works at: http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete Recommended Citation Kentucky High School Athletic Association, "The Athlete, April 1991" (1991). The Athlete. Book 362. http://encompass.eku.edu/athlete/362 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Kentucky High School Athletic Association at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Athlete by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. «.(»««««(iiiW*Pi ' "" "* CTP Official Publication of The Kentucky High School Athletic Association ^^^^^MHjHj Member ol National Federation ol Stale Higti School Associations .lllUU4^VL|4ili!illiiiipPilPP The K.H.S.A.A. Salutes the Winners of the Academic Showcase The sixth annual Sweet 1 6 Academic Showcase was held in Lexington, Kentucky during the week of the Boys' Sweet 1 6 Basketball Tournament. Approximately 1 ,750 students from 209 high schools from 99 counties participated in 1 2 competitions. Regional competitions were held at colleges and universities around the state in January and February. From these sites the top four place finishers in each competition qualified to come to Lexington to compete for scholarships. The finals in 1 2 categories were at Transylvania University. The awards were presented on March 1 5th at a banquet at Marriott's Griffin Gate Resort. A total of $73,350 in scholarships and prizes was awarded. The showcase is funded by an annual televised auction and donations from private corporations.