Short History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View in Website Mode

52A bus time schedule & line map 52A Woodingdean - Brighton - Hangleton View In Website Mode The 52A bus line Woodingdean - Brighton - Hangleton has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Hangleton: 7:00 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 52A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 52A bus arriving. Direction: Hangleton 52A bus Time Schedule 69 stops Hangleton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:00 AM Downs Hotel Falmer Road, Woodingdean Tuesday 7:00 AM Mcwilliam Road, Woodingdean Wednesday 7:00 AM Sea View Way, Woodingdean Thursday 7:00 AM Hunns Mere Way, England Friday 7:00 AM Langley Crescent West End, Woodingdean Saturday Not Operational Sutton Close, Woodingdean Langley Crescent, England Langley Crescent East End, Woodingdean 52A bus Info Balsdean Road, Woodingdean Direction: Hangleton Stops: 69 Heronsdale Road, Woodingdean Trip Duration: 75 min Line Summary: Downs Hotel Falmer Road, Top Of Cowley Drive, Woodingdean Woodingdean, Mcwilliam Road, Woodingdean, Sea View Way, Woodingdean, Langley Crescent West Cowley Drive, England End, Woodingdean, Sutton Close, Woodingdean, Foxdown Road, Woodingdean Langley Crescent East End, Woodingdean, Balsdean Road, Woodingdean, Heronsdale Road, Woodingdean, Top Of Cowley Drive, Woodingdean, Stanstead Crescent, Woodingdean Foxdown Road, Woodingdean, Stanstead Crescent, Woodingdean, Cowley Drive Shops, Woodingdean, Cowley Drive Shops, Woodingdean Ravenswood Drive, Woodingdean, Donnington Road, Green Lane, England Woodingdean, -

Trinity College War Memorial Mcmxiv–Mcmxviii

TRINITY COLLEGE WAR MEMORIAL MCMXIV–MCMXVIII Iuxta fidem defuncti sunt omnes isti non acceptis repromissionibus sed a longe [eas] aspicientes et salutantes et confitentes quia peregrini et hospites sunt super terram. These all died in faith, not having received the promises, but having seen them afar off, and were persuaded of them, and embraced them, and confessed that they were strangers and pilgrims on the earth. Hebrews 11: 13 Adamson, William at Trinity June 25 1909; BA 1912. Lieutenant, 16th Lancers, ‘C’ Squadron. Wounded; twice mentioned in despatches. Born Nov 23 1884 at Sunderland, Northumberland. Son of Died April 8 1918 of wounds received in action. Buried at William Adamson of Langham Tower, Sunderland. School: St Sever Cemetery, Rouen, France. UWL, FWR, CWGC Sherborne. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1904; BA 1907; MA 1911. Captain, 6th Loyal North Lancshire Allen, Melville Richard Howell Agnew Regiment, 6th Battalion. Killed in action in Iraq, April 24 1916. Commemorated at Basra Memorial, Iraq. UWL, FWR, CWGC Born Aug 8 1891 in Barnes, London. Son of Richard William Allen. School: Harrow. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity Addy, James Carlton Oct 1 1910. Aviator’s Certificate Dec 22 1914. Lieutenant (Aeroplane Officer), Royal Flying Corps. Killed in flying Born Oct 19 1890 at Felkirk, West Riding, Yorkshire. Son of accident March 21 1917. Buried at Bedford Cemetery, Beds. James Jenkin Addy of ‘Carlton’, Holbeck Hill, Scarborough, UWL, FWR, CWGC Yorks. School: Shrewsbury. Admitted as pensioner at Trinity June 25 1910; BA 1913. Captain, Temporary Major, East Allom, Charles Cedric Gordon Yorkshire Regiment. Military Cross. -

Accommodation Guide

Screen and Film School 20/21 ——— Accommodation Guide ——— www.screenfilmschool.ac.uk Contents —— Accommocation 3 Estate Agents & Landlords 5 Property Websites 6 House Viewings 6 House Shares 8 Location 9 Transport 10 Frequently Asked Questions 11 Culture 15 Brighton Life 17 Accommodation ------ One essential thing you must ensure you have arranged prior to your studies at Screen and Film School Brighton is your accommodation. Your living arrangement can be an important factor in your success as a student and the Student Support team offers a lot of help with arranging this. We do not have halls of residence at Screen and Film School Brighton, which means you must find housing privately but we have various resources available to help with every step of the process. Brighton has various different types of accommodation available, such as: • Flats • Shared houses • Bedsits • Part-board with a host family However, as Brighton is a university city there is a heavy demand for student accommodation. We advise you to look as early as possible to find a place that suits your needs. We work closely with the following agencies and can introduce you to them so they can work with you to find suitable accommodation. Brighton Accommodation Agency www.baagency.co.uk 01273 672 999 email: [email protected] Harringtons www.harringtonslettings.co.uk 01273 724 000 email: [email protected] www.screenfilmschool.ac.uk Estate Agents and Landlords ------ Alternatively, there are many letting agencies and Jackie Phillips private landlords based in Brighton. If you are going Tel 01273 493409 through a letting agent you will be expected to pay [email protected] (Email) a holding fee, agency fees, a deposit and usually one month’s rent upfront, plus provide a guarantor. -

Nizells-Brochure.Pdf

ANAN EXCLUSIVE EXCLUSIVE DEVELOPMENT OF OF LUXURYNINE LUXURIOUSAPARTMENTS RESIDENCES AND HOUSES ONE NIZELLS AVENUE HOVE LIFESTYLE REIMAGINED One Nizells Avenue is a new The elegant two and three bedroom development of luxurious apartments apartments and three bedroom townhouses and townhouses, ideally positioned all feature intelligently configured, spacious adjacent to an attractive expanse of open plan layouts, with full height glazing landscaped parkland, yet just minutes affording a wonderful stream of natural from the beautiful seafront and buzzing light. A contemporary specification with central Brighton scene. premium materials and designer finishes is complemented by exquisite interior design. Just moments from the doorstep, St Ann’s Each home benefits from private outside Well Gardens is one of Brighton and Hove’s space, the townhouses boasting terraces most treasured city parks, and the perfect and gardens and the penthouse apartment spot to relax and unwind within a captivating opening onto a wraparound terrace with setting of ancient trees, exotic plants and distant horizon views. winding pathways. Nizells Avenue is also perfectly placed to enjoy the limitless bars, eateries, shops and cultural offerings of the local area, whether in laid-back Hove or vibrant Brighton. 1 LOCATION CITY OF SPIRIT Arguably Britain’s coolest, most diverse North Laine forms the cultural centre of the and vibrant city, Brighton and Hove is city, a hotbed of entertainment including an eccentric hotchpotch of dynamic The Brighton Centre and ‘Best Venue in entertainment and culture, energetic the South’, Komedia Brighton. It’s also a nightlife and eclectic shopping, fantastic choice for shopping and eating, with an eating and drinking scene with over 400 independent businesses. -

Groundsure Planning

Groundsure Planning Address: Specimen Address Date: Report Date Report Reference: Planning Specimen Your Reference:Planning Specimen Client:Client Report Reference: Planning Specimen Contents Aerial Photo................................................................................................................. 3 1. Overview of Findings................................................................................................. 4 2. Detailed Findings...................................................................................................... 5 Planning Applications and Mobile Masts Map..................................................................... 6 Planning Applications and Mobile Masts Data.................................................................... 7 Designated Environmentally Sensitive Sites Map.............................................................. 18 Designated Environmentally Sensitive Sites.................................................................... 19 Local Information Map................................................................................................. 21 Local Information Data................................................................................................ 22 Local Infrastructure Map.............................................................................................. 32 Local Infrastructure Data.............................................................................................. 33 Education.................................................................................................................. -

Heritage-Statement

Document Information Cover Sheet ASITE DOCUMENT REFERENCE: WSP-EV-SW-RP-0088 DOCUMENT TITLE: Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’: Final version submitted for planning REVISION: F01 PUBLISHED BY: Jessamy Funnell – WSP on behalf of PMT PUBLISHED DATE: 03/10/2011 OUTLINE DESCRIPTION/COMMENTS ON CONTENT: Uploaded by WSP on behalf of PMT. Environmental Statement Chapter 6 ‘Cultural Heritage’ ES Chapter: Final version, submitted to BHCC on 23rd September as part of the planning application. This document supersedes: PMT-EV-SW-RP-0001 Chapter 6 ES - Cultural Heritage WSP-EV-SW-RP-0073 ES Chapter 6: Cultural Heritage - Appendices Chapter 6 BSUH September 2011 6 Cultural Heritage 6.A INTRODUCTION 6.1 This chapter assesses the impact of the Proposed Development on heritage assets within the Site itself together with five Conservation Areas (CA) nearby to the Site. 6.2 The assessment presented in this chapter is based on the Proposed Development as described in Chapter 3 of this ES, and shown in Figures 3.10 to 3.17. 6.3 This chapter (and its associated figures and appendices) is not intended to be read as a standalone assessment and reference should be made to the Front End of this ES (Chapters 1 – 4), as well as Chapter 21 ‘Cumulative Effects’. 6.B LEGISLATION, POLICY AND GUIDANCE Legislative Framework 6.4 This section provides a summary of the main planning policies on which the assessment of the likely effects of the Proposed Development on cultural heritage has been made, paying particular attention to policies on design, conservation, landscape and the historic environment. -

SIAS Newsletter 061.Pdf

SUSSEX INDUSTRIAL HISTORIC FARM BUILDINGS GROuP ~T~ ARCHAEOLOGY SOCIETY Old farm buildings are among the most conspicuous and pleasing features of the ~ Rcgistcral ChJri'y No_ 267159 traditional countryside. They are also among the most interesting, for they are valuable --------~=~------ and substantial sources of historical knowledge and understanding. NEWSLETTER No.6) ISSN 0263 516X Although vari ous organisations have included old farm build-iogs among their interests there was no s ingle one solely concerned with the subject. It was the absence of such an Price lOp to non-members JANUAR Y 1989 organisation which led to the establishment of the Group in 1985. Membership of the Group is open to individuals and associations. A weekend residential conference, which inc ludes visits to farm buildings of historical interest, is held CHIEF CONTENTS annually. The Group also publishes a Journal and issues regular newsletters to members. Annual Reports - Gen. Hon. Secretary, Treasurer If you wish t o join, send your subscription (£5 a year for individuals) to the Area Secretaries' Reports Secretary, Mr Roy Bridgen, Museum of English Rural Life, Box 229, Whiteknights, Reading In auguration of Sussex Mills Group RG2 2AG. Telephone 0731! 875123. New En gland Road railway bridges - Brighton Two Sussm: Harbours in the 18th century MEMBERSHIP C HANGES Brighton & Hcve Gazette Year Book New Members Mrs B.E. Longhurst 29 Alfriston Road, Worthing BN I4 7QS (0903 200556) '( II\R Y DATES Mrs E. Riley-Srnith E\rewhurst, Loxwood, Nr. Bi lill1 gshurst RHI/i OR J ( O~03 75235 Sunday, 5th Ma rch. Wo rking vi sit to Coultershaw Pump, Pe tworth. -

SUSSEX. [POST OFFICE Giles Mrs

2906 BRIGHTON. SUSSEX. [POST OFFICE Giles Mrs. 3 Chicl1ester p1. Kemp town Griffith Mrs. 26 Montpeliel"strett Hardy William, 9 Waterloo place GiU Airs. Dunwoody, 28 Prestonvlle.rd Griffiths 81. Pryce, 2 Selborne rd. Hove Hargreaves Rev. Joseph, [Weslepan], Gilpin Mrs. 5 Pre!-tomille terrace Grimble Mrs. Amelia, 1 Portland place 4 Stanford road Glaisyer l\fiss, 45 Gardner street Gritton Mrs. 8 Lewes crescent Harley Miss, 52 Egremont place Glanville Wm. Gordon. 11 Richmnd. rrl Groombrirfge Daniel TJ;}os. Leopold road Harmar Wm. Bycroft, 17 Cbesham pi Glac:kin Rev. John [Baptist], 49 Rose Grounds David, 83 Ditchling rise Harper Edward, 8 Brunswick terrace Hill terrace Grover Samuel John, 8 Shafteshnry rd Harris Charles John, 4: Pelham square • Glayzer Thomas, 96 London road Groves John, 9 Ventnor viis. Cliftonville Harris Henry Edward, 17 Cannon place Glyn Mrs. 22 Brunswick square Grunow Mrs. 2 Belvedere terrace Harris James Sidney, 81 Upper North st Godbold George, 14 Hamilton road Guerin Mrs. 7 Seafield, Cliftonville Harris Miss, 6 Arundel ter. Kemp town Godfree Georg~ Stephen. 65 Preston rd Guillaume Miss,1 Oshorne vils.Cliflonvl Harris 1\Iiss, 66 Lansdowneplace, Hove Godwin Jas. EyleQ, 65 Ditchling rise Guimaraens Mrs. 6 Round Hill crescent HarriR Mrs. 48 Great College street Godwin Mrs. 44 Buckingham road Gunn Alfred, 115 Ditchling rise Harris Mrs. IO Sussex square Goff Miss, IO St. John's terrace, Hove Gnnn Mrs. 4 Se:Jfield, Cliftonvil!e Harris Mrs. 3 Waterloo place Golden Charles, 30 Clifton street Gunn Stephen, 34 East street Harrison Miss, 35 Grand parade Golden Charles, 16 l.:ollege road Gurbs Stephen, 35 Montpelier !'ltreet Harrison Mr~. -

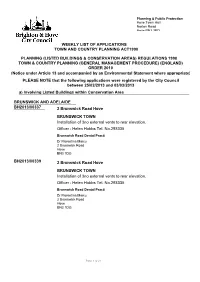

Cadenza Document

Planning & Public Protection Hove Town Hall Norton Road Hove BN3 3BQ WEEKLY LIST OF APPLICATIONS TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING ACT1990 PLANNING (LISTED BUILDINGS & CONSERVATION AREAS) REGULATIONS 1990 TOWN & COUNTRY PLANNING (GENERAL MANAGEMENT PROCEDURE) (ENGLAND) ORDER 2010 (Notice under Article 13 and accompanied by an Environmental Statement where appropriate) PLEASE NOTE that the following applications were registered by the City Council between 25/02/2013 and 03/03/2013 a) Involving Listed Buildings within Conservation Area BRUNSWICK AND ADELAIDE BH2013/00337 2 Brunswick Road Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Installation of 3no external vents to rear elevation. Officer : Helen Hobbs Tel. No.293335 Brunswick Road Dental Practice Dr Florentina Marcu 2 Brunswick Road Hove BN3 1DG BH2013/00339 2 Brunswick Road Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Installation of 3no external vents to rear elevation. Officer : Helen Hobbs Tel. No.293335 Brunswick Road Dental Practice Dr Florentina Marcu 2 Brunswick Road Hove BN3 1DG Page 1 of 21 BH2013/00459 Flat 1 49 Brunswick Square Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Installation of air vent to front elevation. (Retrospective). Officer : Mark Thomas Tel. No.292336 Dr Robert Towler Hatchwell & Draper FLAT 1 The Agora 49 Brunswick Square Ellen Street Hove Hove BN3 1EF BN3 3LS BH2013/00510 Flat 53 Embassy Court Kings Road Brighton REGENCY SQUARE Internal alterations including removal of airing cupboard from bathroom, moving door to master bedroom, formation of double doors between drawing room and living and drawing room and kitchen. Officer : Christopher Wright Tel. No.292097 Paul Dennsion Andrew Birds Flat 53 76 Embassy Court Embassy Court Kings Road Kings Road Brighton Brighton BN1 2PY BN1 2PX BH2013/00543 Flat 8 18-19 Adelaide Crescent Hove BRUNSWICK TOWN Internal alterations to layout of flat. -

LOCUS FOCUS Forum of the Sussex Place-Names Net

ISSN 1366-6177 LOCUS FOCUS forum of the Sussex Place-Names Net Volume 2, number 1 • Spring 1998 Volume 2, number 1 Spring 1998 • NET MEMBERS John Bleach, 29 Leicester Road, Lewes BN7 1SU; telephone 01273 475340 -- OR Barbican House Bookshop, 169 High Street, Lewes BN7 1YE Richard Coates, School of Cognitive and Computing Sciences, University of Sussex, Brighton BN1 9QH; telephone 01273 678522 (678195); fax 01273 671320; email [email protected] Pam Combes, 37 Cluny Street, Lewes BN7 1LN; telephone 01273 483681; email [email protected] [This address will reach Pam.] Paul Cullen, 67 Wincheap, Canterbury CT1 3RX; telephone 01233 612093 Anne Drewery, The Drum, Boxes Lane, Danehill, Haywards Heath RH17 7JG; telephone 01825 740298 Mark Gardiner, Department of Archaeology, School of Geosciences, Queen’s University, Belfast BT7 1NN; telephone 01232 273448; fax 01232 321280; email [email protected] Ken Green, Wanescroft, Cambrai Avenue, Chichester PO19 2LB; email [email protected] or [email protected] Tim Hudson, West Sussex Record Office, County Hall, Chichester PO19 1RN; telephone 01243 533911; fax 01243 533959 Gwen Jones, 9 Cockcrow Wood, St Leonards TN37 7HW; telephone and fax 01424 753266 Michael J. Leppard, 20 St George’s Court, London Road, East Grinstead RH19 1QP; telephone 01342 322511 David Padgham, 118 Sedlescombe Road North, St Leonard’s on Sea TH37 7EN; telephone 01424 443752 Janet Pennington, Penfold Lodge, 17a High Street, Steyning, West Sussex BN44 3GG; telephone 01903 816344; fax 01903 879845 Diana -

SUSSEX. [KELL1' 1S Greenall Richd.7New Church Rd.Hove Gromrw Miss, 2::; St

18.2 BIUGBTON AND BOVI. SUSSEX. [KELL1' 1S Greenall Richd.7New Church rd.Hove Gromrw Miss, 2::; St. Michael's place Hall Arthur P. 18 Chatsworth road Greene Miss. 34 .Adelaide cres. Hove Groome Mrs. r8 Hanover crescent Hall Donald George M . .A., M.D. 29 Greenfield Harry, 62 Rutland gar- Gmss Mr~. 5 Eaton court, Eaton pl. Brunswick square, Hove de m, Hove Kemp tDwn Hall Frederick J. 8 Grand parade , Greenfield. Wm.J..lfred, 46 Stanf.ord uv Grove-Morris Mrs.W-olstonbury lodgf', Hall George Edward, 2 Havelock rd. Greengrass Edward Josiah, 65 Stan- Old Shoreham road, Hove Preston ford avenue , Grover Herbert, 3 Powis grove Hall Mrs. Kismet, Dyke road Greenhill Rt.S.52 Denmark viis. Hove Groves Jlllmes Godfrey, T.'he Retreat, Hall Mrs. 43 Langdale gardens, Hon~ Greening Benjamin Charles, 32 Nor- Hollingdean road Hall Mrs. 6 Pembroke avenue, Hove ton road, Hove Groves Jn, 4 Sudeley ter.Kemp town Hall Mrs. 21 West drive, Queen's pk Greenwood John Ernest, 67 Fonthill Groves Thomas John, r Harrington Hall Mrs. Joseph, 17 Tisbury rd.Hove road, Hove road, Presbon Hall Mrs. M. A.. II5 Marine parade Greenwood Mrs. ro Aymer rd. Hove Gruselle Ernest, 215 Preston drove Hall PhilipLenham,64 Tisbury rd.Hve Greenwood Mrs.B New Town rd.Hove Guest Mrs. x Lancaster road Hall Wilfred George Oarlton B.C.L .• Greenwood Mrs. 4 York avenue, Hove Guildford George By. 2 Tilbury pi M.A. rr5 Marine parade Greenwood Wm.37Florence rd.Preston Guimaraens Frederick Alexander, 17 Hall William Jas. 127 Preston road Greenyer Chester Mayo, 15 Chesham Wilbury road, Hove Hallam Fredk. -

Ladies Mile Road, Mile End Cottages, 1-6 Historic Building No CA Houses ID 75 & 275 Not Included on Current Local List

Ladies Mile Road, Mile End Cottages, 1-6 Historic Building No CA Houses ID 75 & 275 Not included on current local list Description: Brown brick terrace of six cottages, with red brick dressings and a clay tile roof. Two storey with attic; a matching dormer window has been inserted into the front roof slope of each property. The terrace is set at right angles to the road, at the western end of Ladies Mile Road, a drove road which became popular as a horse-riding route in the late 19th century. The properties themselves are of late 19th century date. They are first shown on the c.1890s Ordnance Survey map. A complex of buildings is shown to the immediate west of the cottages on this map. Arranged around a yard, this likely formed agricultural buildings or service buildings associated with Wootton House. The architectural style and physical association of the cottages to these buildings and the drove road suggests they may have formed farmworkers’ cottages. A Architectural, Design and Artistic Interest ii A solid example of a terrace of worker’s cottages B Historic and Evidential Interest ii Illustrative of the agricultural origins of Ladies Mile Road as a drove road and associated with the historic agricultural village of Patcham. C Townscape Interest ii Outside of Patcham Conservation Area, but associated with its history and contributes positively to the street scene F Intactness i Although some of the windows have been replaced, and there are modern insertions at roof level (particularly to the rear), the terrace retains a sense of uniformity and completeness Recommendation: Include on local list Lansdowne Place, Lansdowne Place Hotel, Hove Historic Building Brunswick Town Hotel ID 128 + 276 Not included on current local list Description: Previously known as Dudley Hotel.