002GFC1004 I-112 1 Copy.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 World Championship Cheese Contest

2020 World Championship Cheese Contest Winners, Scores, Highlights March 3-5, 2020 | Madison, Wisconsin ® presented by the Cheese Reporter and the Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association World Cheese Contest ® Champions 2020 1998 1976 MICHAEL SPYCHER & PER OLESEN RYKELE SYTSEMA GOURMINO AG Denmark Netherlands Switzerland 1996 1974 2018 HANS DEKKERS GLEN WARD MICHEL TOUYAROU & Netherlands Wisconsin, USA SAVENCIA CHEESE USA France 1994 1972 JENS JENSEN DOMENICO ROCCA 2016 Denmark Italy TEAM EMMI ROTH USA Fitchburg, Wisconsin USA 1992 1970 OLE BRANDER LARRY HARMS 2014 Denmark Iowa, USA GERARD SINNESBERGER Gams, Switzerland 1990 1968 JOSEF SCHROLL HARVEY SCHNEIDER 2012 Austria Wisconsin, USA TEAM STEENDEREN Wolvega, Netherlands 1988 1966 DALE OLSON LOUIS BIDDLE 2010 Wisconsin, USA Wisconsin, USA CEDRIC VUILLE Switzerland 1986 1964 REJEAN GALIPEAU IRVING CUTT 2008 Ontario, Canada Ontario, Canada MICHAEL SPYCHER Switzerland 1984 1962 ROLAND TESS VINCENT THOMPSON 2006 Wisconsin, USA Wisconsin, USA CHRISTIAN WUTHRICH Switzerland 1982 1960 JULIE HOOK CARL HUBER 2004 Wisconsin, USA Wisconsin, USA MEINT SCHEENSTRA Netherlands 1980 1958 LEIF OLESEN RONALD E. JOHNSON 2002 Denmark Wisconsin, USA CRAIG SCENEY Australia 1978 1957 FRANZ HABERLANDER JOHN C. REDISKE 2000 Austria Wisconsin, USA KEVIN WALSH Tasmania, Australia Discovering the Winning World’s Best Dairy Results Wisconsin Cheese Makers Association was honored to host an international team of judges and an impressive array of samples of 2020 cheese, butter, yogurt and dairy ingredients from around the globe at the 2020 World Championship Cheese Contest March 3-5 in Madison. World Champion It was our largest event ever, with a breath-taking 3,667 entries from Michael Spycher, Mountain 26 nations and 36 American states. -

Bovine Benefactories: an Examination of the Role of Religion in Cow Sanctuaries Across the United States

BOVINE BENEFACTORIES: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ROLE OF RELIGION IN COW SANCTUARIES ACROSS THE UNITED STATES _______________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board _______________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ________________________________________________________________ by Thomas Hellmuth Berendt August, 2018 Examing Committee Members: Sydney White, Advisory Chair, TU Department of Religion Terry Rey, TU Department of Religion Laura Levitt, TU Department of Religion Tom Waidzunas, External Member, TU Deparment of Sociology ABSTRACT This study examines the growing phenomenon to protect the bovine in the United States and will question to what extent religion plays a role in the formation of bovine sanctuaries. My research has unearthed that there are approximately 454 animal sanctuaries in the United States, of which 146 are dedicated to farm animals. However, of this 166 only 4 are dedicated to pigs, while 17 are specifically dedicated to the bovine. Furthermore, another 50, though not specifically dedicated to cows, do use the cow as the main symbol for their logo. Therefore the bovine is seemingly more represented and protected than any other farm animal in sanctuaries across the United States. The question is why the bovine, and how much has religion played a role in elevating this particular animal above all others. Furthermore, what constitutes a sanctuary? Does -

A Guide to Kowalski's Specialty Cheese Read

Compliments of Kowalski’s WWW.KOWALSKIS.COM A GUIDE TO ’ LOCALOUR FAVORITE CHEESES UNDERSTANDING CHEESE TYPES ENTERTAINING WITH CHEESE CHEESE CULTURES OF THE WORLD A PUBLICATION WRITTEN AND PRODUCED BY KOWALSKI’S MARKETS Printed November 2015 SPECIALTY CHEESE EXPERIENCE or many people, Kowalski’s Specialty Cheese Department Sadly, this guide could never be an all-inclusive reference. is their entrée into the world of both cheese and Kowalski’s Clearly there are cheese types and cheesemakers we haven’t Fitself. Many a regular shopper began by exclusively shopping mentioned. Without a doubt, as soon as this guide goes to this department. It’s a tiny little microcosm of the full print, our cheese selection will have changed. We’re certainly Kowalski’s experience, illustrating oh so well our company’s playing favorites. This is because our cheese departments are passion for foods of exceptional character and class. personal – there is an actual person in charge of them, one Cheese Specialist for each and every one of our 10 markets. When it comes to cheese, we pay particular attention Not only do these specialists have their own faves, but so do to cheeses of unique personality and incredible quality, their customers, which is why no two cheese sections look cheeses that are perhaps more rare or have uncommon exactly the same. But though this special publication isn’t features and special tastes. We love cheese, especially local all-encompassing, it should serve as an excellent tool for cheeses, artisanal cheeses and limited-availability treasures. helping you explore the world of cheese, increasing your appreciation and enjoyment of specialty cheese and of that Kowalski’s experience, too. -

62 Final List of 2019 ACS Judging & Competition Winners RC BUTTERS

Final List of 2019 ACS Judging & Competition Winners RC BUTTERS Salted Butter with or without cultures - made from cow's milk 3rd PLACE Organic Valley Salted Butter CROPP Cooperative/Organic Valley, Wisconsin Team Chaseburg 2nd PLACE CROPP/Organic Valley Salted Butter CROPP Cooperative/Organic Valley, Wisconsin Team McMinnville 1st PLACE Brethren Butter Amish Style Handrolled Salted Butter Graf Creamery Inc., Wisconsin Roy M. Philippi RO BUTTERS Unsalted Butter with or without cultures - made from cow's milk 3rd PLACE Cabot Unsalted Butter Cabot Creamery Cooperative, Massachusetts Team West Springfield 3rd PLACE Organic Valley Cultured Butter, Unsalted CROPP Cooperative/Organic Valley, Wisconsin Team Chaseburg 2nd PLACE CROPP/Organic Valley Pasture Butter, Cultured CROPP Cooperative/Organic Valley, Wisconsin Team McMinnville 1st PLACE Organic Valley European Style Cultured Butter, Unsalted CROPP Cooperative/Organic Valley, Wisconsin Team Chaseburg P a g e 1 | 62 RM BUTTERS Butter with or without cultures - made from goat's milk 3rd PLACE Celebrity Butter (Salted) Atalanta Corporation/Mariposa Dairy, Ontario Pieter Van Oudenaren 2nd PLACE Bella Capra Goat Butter Sierra Nevada Cheese Company, California Ben Gregersen QF CULTURED MILK AND CREAM PRODUCTS Creme Fraiche and Sour Cream Products - made from cow's milk 3rd PLACE Crema Supremo Sour Cream V&V Supremo Foods, Illinois Team Michoacan 2nd PLACE Creme Fraiche Sierra Nevada Cheese Company, California Ben Gregersen 1st PLACE Creme Agria (Sour Cream) Marquez Brothers International, Inc., California Marquez Brothers International, Inc. QK CULTURED MILK AND CREAM PRODUCTS Kefir, Drinkable Yogurt, Buttermilk, and Other Drinkable Cultured Products - all milks 3rd PLACE Karoun Whole Milk Kefir Drink Karoun Dairies LLC, California Jaime Graca P a g e 2 | 62 2nd PLACE Jocoque Marquez Brothers International, Inc., California Marquez Brothers International, Inc. -

Traveler's Guide to America's Dairyland

13 159 150 24 38 94 44 144 108 124B 8 19 124A 57 120 106 166 5 129 15 135 78 64 63 58 154 157 25 168 89 99 75 54 114 136 96 79 53 12 164 116 102 156 128 49 61 48 90 139 55 82 115 110 86 98 167 133 155 97 127 118 100 74 17 40 161 76 151 132 81 143 4 111 163 153 34 43 69 122 84 65 77 103 28 85 72 7 109 29 59 66 71 11 112 101 145 160 91 33 162 36 123 141 27 119 107 125 46 104 121 134 39 142 14 35 32 83 52 73 93 95 3 70 62 30 21E 21A 152 31 6 42 105 26 16 56 21B&C 158A 158B 126 113 10 165 50 107 68 41 51 87 146 131 2 23 37 20 22 149 80 92 137 60 148 169 1 47 147 9 21D 140 130 88 67 18 117 138 45 1) 14F Alp and Dell Cheese Store www.alpanddellcheese.com 10) 13G Bavaria Sausage and Cheese Chalet www.bavariasausage.com 657 2nd St., Monroe, WI 53566 Ph: 608.328.3355 6317 Nesbitt Rd., Madison, WI 53719 Ph: 608.271.1295 Alp and Dell Cheese Store offers a wide selection of locally produced cheese and sausages as Family owned since 1962. Award-winning authentic German sausage made by our Master well as ice cream, candy, wines from around the world, locally brewed beers and cheese-related Sausage Maker. -

Dec/Jan 2008

SPECIAL SECTION 2008 Specialty Cheese Guide Dec./Jan. ’08 Deli $14.95 BUSINESS Also Includes The American Cheese Guide ALSO INSIDE Entrées Natural Meats Italian Deli Salami Reader Service No. 107 DEC./JAN. ’08 • VOL. 12/NO. 6 Deli TABLE OF CONTENTS BUSINESS FEATURES Merchandising Entrées In The Deli ..............17 Fresh is the buzzword sparking a revolution in today’s supermarket industry. COVER STORY PROCUREMENT STRATEGIES Natural Deli Meats ........................................59 More retailers are responding to consumer concern for both a more healthful product and animal welfare. MERCHANDISING REVIEW Viva Italy! ......................................................63 Learning about the background of imported Italian deli products spurs effective marketing and increased profits. DELI MEATS Salami And Cured Meat: Renaissance With An Ethnic Flair ..................69 Effectively merchandise a range of salami and cured meats as high-end unique products. SPECIAL SECTION......................19 1122 2008 COMMENTARY EDITOR’S NOTE Specialty The Specialty Cheese Challenge/Opportunity..................................6 Cheese Guide It may sound like a burden — can’t we just sell product? — but it really is the opportunity. PUBLISHER’S INSIGHTS 2008 Will Be An Interesting Year...................8 From cause marketing and the invasion of the Brits to the greening of politics, 2008 will prove to be a pivotal year. MARKETING PERSPECTIVE There’s No Place Like You For The Holidays ..................................73 You can mount any merchandising -

French Sheep's Milk Cheese, Esquirrou, Is World Champion

Volume 38 March 9, 2018 Number 8 French sheep’s milk cheese, Like us on Facebook and follow us on Twitter! Esquirrou, is World Champion A MADISON, Wis. — A hard First runner-up in the con- The World Championship Austria; Le Maréchal made sheep’s milk cheese called test, with a fi nal round score of Cheese Contest, initiated in by Fromagerie Le Maréchal INSIDE Esquirrou, made in France at 98.267, is Arzberger Ursteirer, a 1957, is the largest technical SA, Granges-Marnand, Vaud, Mauleon Fromagerie by Michel hard cow’s milk cheese aged in cheese, butter, and yogurt com- Switzerland; Sartori Reserve ✦ Guest column: Touyarou and imported by a silver mine and made by Franz petition in the world. A team Espresso BellaVitano made by ‘Prevention and control of Savencia Cheese USA of New Moestl and Team of Almenland of 56 internationally-renowned Mike Matucheski, Sartori Co., yeast and molds in cheese.’ Holland, Pennsylvania, has Stollenkäse in Passail, Austria. judges evaluated all entries over Antigo, Wisconsin; De Graafst- For details, see page 4. been named the 2018 World Mont Vully Bio — a raw milk the three-day competition. room Oud made by De Graaf- Champion Cheese. cheese washed with Pinot Noir In addition to the champion stroom, Bleskensgraaf, Zuid ✦ Partnership fi nalized Earning a score of 98.376 out wine and made by Ewald Scha- and two runners-up, the top 20 Holland, Netherlands; Cheb- for Michigan facility. of 100 in last night’s fi nal judging fer of Fromagerie Schafer in fi nalists of the contest include: rie made by Woolwich Dairy’s For details, see page 5. -

Relay for Life Fall Cheese Fundraiser Order Form RELAY for LIFE OF

Relay For Life Fall Cheese Fundraiser Order Form Relay For Life teams are selling cheese as part of our fundraising efforts supporting the American Cancer Society and its mission of saving lives through education, advocacy, research and services. The quality products we are selling come from the Wisconsin Dairy State Cheese Company, who promotes cheese products made in Wisconsin! Cheese is great gift or addition to any celebration. Boxes for mailing are available at bottom of the list. Thank you for your support in the fight against cancer! Total TYPES OF CHEESE (1# unless noted) Price Sold At Qty Amount RELAY FOR LIFE OF: ________________ Merlot Cheese – Seasonal Feature $10.50 Colby $4.75 TEAM/Team Member: Co-Jack $5.00 _____________________ Monterey Jack $4.75 PURCHASER NAME: Jalapeno Monterey Jack $5..25 ____________________ Green Olive Monterey Jack $5.75 Cranberry Jack – Seasonal Feature $6.00 PURCHASER PHONE Mild Cheddar $4.75 NUMBER: ___________ Sharp Cheddar $6.00 EMAIL: _______________ Havarti $5.25 Havarti Dill $5.50 Gouda $6.00 Payment must be made at Smoked Gouda $6.50 the time the order is placed. Please make checks Provolone $6.75 payable to: Mozzarella (3% fat) $5.00 WI Dairy State Cheese Parmesan (Whole) $6.75 Swiss Lace (Low Fat) $7.00 Cheese delivery date is: Baby Swiss $6.00 November 4, in time for the holidays and gift giving. American Cheese (sliced) $6.25 Pick up location and time Farmer’s Cheese $5.25 will be communicated to Blue Cheese $6.50 those participating. Buffalo Wing $5.25 TOTAL ITEMS Mushroom & Leek $6.00 -

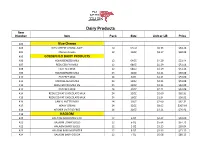

Dairy Products Item Number Item Pack Size Unit Or LB Price

Dairy Products Item Number Item Pack Size Unit or LB Price 402 Blue Cheese 403 BLEU CHEESE CHUNK--SALE 10 3.5 oz $6.35 $63.46 404 Chicken Franks 12 16OZ $3.17 $38.08 405 GOLDEN FLO DAIRY PRODUCTS 406 HOMOGENIZED MILK 12 64OZ $4.29 $51.44 407 REDUCED FAY MILK 12 64OZ $4.29 $51.44 408 FAT FREE MILK 12 64OZ $4.29 $51.44 409 HOMOGENIZED MILK 24 32OZ $2.21 $53.08 410 FAT FREE MILK 24 320Z $2.21 $53.08 411 HOMOGENIZED MILK 24 32OZ $2.21 $53.08 412 REDUCED FAY MILK 1% 24 32OZ $2.21 $53.08 413 FAT FREE MILK 24 32OZ $2.21 $53.08 414 REDUCED FAT CHOCOLATE MILK 24 32OZ $2.60 $62.31 415 REDUCED FAT CHOCOLATE MILK 24 16OZ $1.54 $36.92 416 J AND J BUTTER MILK 24 32OZ $2.60 $62.31 417 HEAVY CREAM 24 32OZ $8.65 $207.69 418 KOSHER LACTOSE FREE 24 32OZ $3.21 $76.92 419 HAOLOM 420 HALAOM MUENSTER SLCD 12 6 OZ $4.42 $53.00 421 HALAOM EDAM SLICED 12 6 OZ $5.64 $67.73 422 HALAOM SMKD SLICES 12 5 OZ $5.25 $63.04 423 HALAOM BABY MUENSTER 12 8 OZ $5.93 $71.15 424 HALAOM BABY GOUDA 12 7 OZ $6.68 $80.13 Dairy Products Item Number Item Pack Size Unit or LB Price 425 HALAOM BABY MOZZARELL 12 8OZ $5.93 $71.15 426 HALOAM BABY MONT JACK 12 8OZ $5.93 $71.15 427 HAOLAM CHEDDAR STIK Y 12 8 OZ $5.61 $67.31 428 HALAOM CHEDDAR WHT ST 12 8OZ $5.61 $67.31 429 HAOLAM WISCONSIN SWIS 12 6 OZ $6.82 $81.85 430 HAOLAM SLICED HAVARTI 12 7 OZ $6.74 $80.88 431 HAOLAM DLL HAVARTI CH 12 7 OZ $6.85 $82.15 432 HAOLAM SLICE PROVOLON 12 6 OZ $5.12 $61.42 433 HAOLAM RED FAT MOZZ S 12 6 OZ $5.84 $70.08 434 HAOLAM LT SL MONTER/J 12 6 OZ $5.84 $70.08 435 HAOLAM SLC CHDR WHITE 12 6 OZ $4.50 $53.96 436 HAOLAM YOGURT & HERB 12 6 OZ $5.84 $70.08 437 HAOLAM STRING CHEESE 12 18 OZ $15.88 $190.50 438 HAOLAM STRING CHEESE 12 6 OZ $6.07 $72.87 439 HAOLAM GRATED PARMESA 12 3.5 OZ $6.72 $80.65 440 HAOLOM SWITZERLAND SWISS SL 12 6 OZ $9.97 $119.65 441 HAOLAM GRUYERE TRIANG 12 6 OZ $9.62 $115.38 442 J AND J Cottage Cheese 443 16 oz. -

US Cheese Contest

U.S. Cheese Contest CHAMPIONS TEAM GUGGISBERG RANDY KRAHENBUHL GIANNI TOFFOLON Guggisberg Cheese Fair Oaks Dairy Products Belgioioso Cheese Millersburg, Ohio Fair Oaks, Indiana Denmark, Wisconsin 2019 2005 1991 MIKE MATUCHESKI MICHAEL GINGRICH LARRY MARTEN Sartori Company Uplands Cheese Company Cloverleaf Cheese Company Antigo, Wisconsin Dodgeville, Wisconsin Stanley, Wisconsin 2017 2003 1989 TEAM GUGGISBERG CHRISTINE FARRELL TODD JAKOBI Guggisberg Cheese Old Chatham Sheepherding Co. Sorrento Lactalis Old Chatham, New York Arpin, Wisconsin Millersburg, Ohio 2015 2001 1987 HOLLAND’S FAMILY CHEESE TEAM MILFRED SEVERSON FRITZ KOPP Klondike Cheese Company Deppeler Cheese Factory Holland’s Family Cheese Monroe, Wisconsin Monroe, Wisconsin Thorp, Wisconsin 2013 1999 1985 KATIE HEDRICH RICK RUFER JAMES MEIVES Kolb Lena Bresse Bleu Valley View Cheese Factory LaClare Farms Specialties Watertown, Wisconsin South Wayne, Wisconsin Chilton, Wisconsin 2011 1997 1983 JOHN GRIFFITHS CHARLES MALKASSIAN LOUIS LUYKX Vella Cheese Company of California Land O’ Lakes Sartori Foods Sonoma, California Kiel, Wisconsin Antigo, Wisconsin 2009 1995 1981 KEN ROOT MIKE BRENNENSTUHL Land O’ Lakes McCadam Cheese Company Denmark, Wisconsin Chateaugay, New York 2007 1993 2 UNITED STATES CHAMPIONSHIP CHEESE CONTEST WINNING RESULTS GUGGISBERG EYES SECOND SUCCESS A petite Baby Swiss wheel made by Guggisberg Cheese in 2019 UNITED STATES Millersburg, Ohio earned the title 2019 U.S. Champion Cheese in March, a mere four years after Guggisberg Premium Swiss GRAND CHAMPION topped the U.S. Championship Cheese Contest. Richard Guggisberg Marieke Gouda of Thorp, Wisconsin, also continued their winning ways, earning both & Team Guggisberg the First and Second Runner-Up positions this year, after besting the competition in Doughty Valley 2013.Yet, the frequency of their success had no tempering effect on cheesemakers Richard Guggisberg and Marieke Penterman, with both appearing awed and thrilled at Guggisberg Cheese the Contest’s crowning event, Cheese Champion. -

(19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub

US 20140134292A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2014/0134292 A1 Petersen (43) Pub. Date: May 15, 2014 (54) PRODUCTION OF CHEESE WITH S. Publication Classi?cation THERMOPHILUS (51) Int. Cl. (75) Inventor: Lars Wexoe Petersen, Muskego, WI A23C 19/032 (2006.01) (US) A23C 19/076 (2006.01) C12R 1/46 (2006.01) (73) Assignee: DUPONT NUTRITION (52) us CL BIOSCIENCES APS, COPENHAGEN CPC ............... .. A23C 19/032 (2013.01); C12R 1/46 (DK) (2013.01); A23C 19/076 (2013.01) USPC ......................... .. 426/36; 435/253.4; 426/582 (21) Appl. No.: 14/112,892 (22) PCT Filed: Jan. 12, 2012 (57) ABSTRACT (86) PCT No.1 PCT/U512/21113 The present invention provides methods, compositions, and 371 1 systems for producing cheese With S. lhermophilus and a § (6X )’_ urease inhibitor, and for producing cottage cheese With S. (2), (4) Date- Jan“ 7’ 2014 Zhermophilus that is partially or completely de?cient in its . ability to release ammonia from urea. The present invention Related U's' Apphcatlon Data also provides methods, compositions, and systems for reduc (60) Provisional application No. 61/477,211, ?led on Apr. ing the amount of open texture (e. g., slits, cracks, or fractures) 20, 2011. in gassy cheeses, such as cheddar cheese. Patent Application Publication M y 15, 2014 Sheet 1 0f 3 US 2014/0134292 A1 Activity Pro?le at 35°C 1% fresh mllk (‘0)Temp Time (mins) - - - Ladococci (570 g) and ur(+) S. thermophilus (140 g) - i- — Lac'bococci (570 g) and ur(+) S. thermophilus (140 g) —B——Lactococci (640 g) and ur(-)S. -

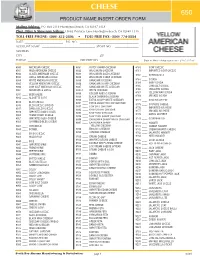

Order Form | Cheese Product Name Inserts (650)

CHEESE 650 PRODUCT NAME INSERT ORDER FORM Mailing Address: P.O. Box 2118 Huntington Beach, CA 92647-0118 Plant, Office & Showroom Address: 15662 Producer Lane Huntington Beach, CA 92649-1310 TOLL-FREE PHONE: (800) 852-2806 • TOLL-FREE FAX: (800) 774-8884 DATE __________________________ P.O. NO. ________________________________________ ACCOUNT NAME ____________________________________ STORE NO. ________________ ADDRESS __________________________________________________________________________ CITY __________________________________________________ ZIP ______________________ PHONE __________________________________ ORDERED BY __________________________ Black on White - Actual size shown - 2 5/16” x 1 5/16” 9000 ____ AMERICAN CHEESE 9081 ____ SUPER SHARP CHEDDAR 9160 ____ GOAT CHEESE 9001 ____ MILD AMERICAN CHEESE 9082 ____ WISCONSIN CHEDDAR 9161 ____ IMPORTED GOAT CHEESE 9002 ____ SLICED AMERICAN CHEESE 9083 ____ WISCONSIN AGED CHEDDAR 9162 ____ GORGONZOLA 9003 ____ SWISS AMERICAN CHEESE 9084 ____ WISCONSIN SHARP CHEDDAR 9004 ____ WHITE AMERICAN CHEESE 9085 ____ CANADIAN CHEDDAR 9163 ____ GOUDA 9005 ____ YELLOW AMERICAN CHEESE 9086 ____ CANADIAN SHARP CHEDDAR 9164 ____ BABY GOUDA 9006 ____ LOW SALT AMERICAN CHEESE 9087 ____ CANADIAN WHITE CHEDDAR 9165 ____ LOW SALT GOUDA 9007 ____ AMERICAN & SWISS 9087-1 ___ WHITE CHEDDAR 9166 ____ UNSALTED GOUDA 9088 ____ GOLDEN AGED CHEDDAR 9167 ____ YELLOW WAX GOUDA 9011 ____ BEER KAESE 9168 ____ SMOKED GOUDA 9012 ____ ALOUETTE CUPS 9089 ____ BLACK DIAMOND CHEDDAR 9090 ____ EXTRA SHARP WHITE CHEDDAR