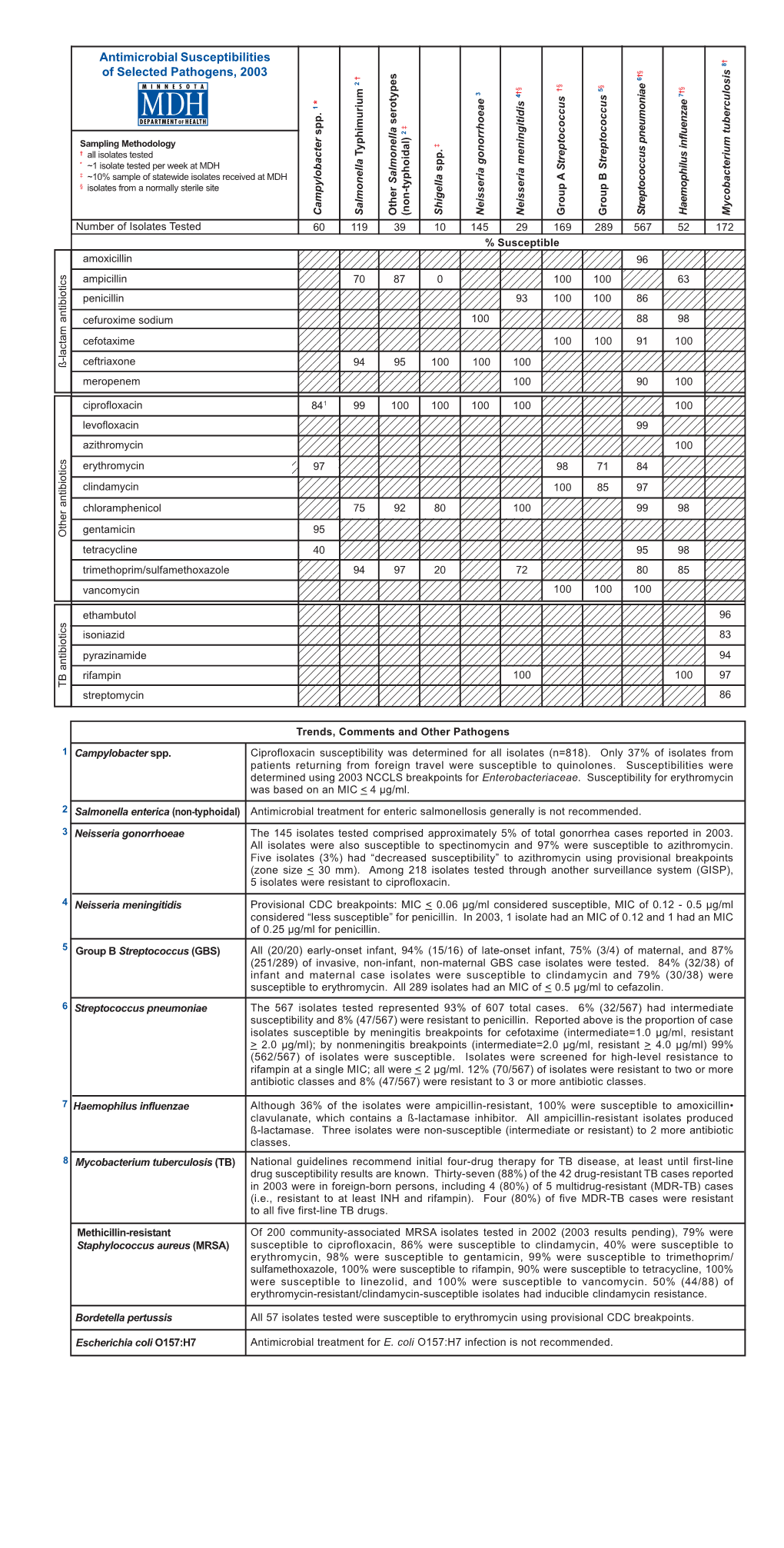

(Antibiogram) 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaii State Department of Health Tetanus Factsheet

TETANUS ABOUT THIS DISEASE Tetanus is an infection caused by a bacterium called Clostridium tetani. Spores of tetanus bacteria are everywhere in the environment, including soil, dust, and manure. These spores develop into bacteria when they enter the body through breaks in the skin, usually through injuries from contaminated objects. Clostridium tetani produce a toxin (poison) that causes painful muscle contractions. Tetanus is often called “lockjaw” because the first sign is most commonly spasms of the jaw muscles. Tetanus can lead to serious health problems, including being unable to open the mouth and having trouble swallowing and breathing, possibly leading to death (10% to 20% of cases). Tetanus is uncommon in the United States, with an average of 30 reported cases each year. Nearly all cases of tetanus in the U.S. are among people who have never received a tetanus vaccine, or adults who don’t stay up to date on their 10-year booster shots. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS Symptoms of tetanus include: • Jaw cramping • Sudden, involuntary muscle tightening (muscle spasms) – often in the stomach • Painful muscle stiffness all over the body • Trouble swallowing • Jerking or staring (seizures) • Headache • Fever and sweating • Changes in blood pressure and a fast heart rate. Serious health problems that can happen because of tetanus include: • Laryngospasm (uncontrolled/involuntary tightening of the vocal cords) • Fractures (broken bones) • Hospital-acquired infections (Infections caught by a patient during a hospital stay) • Pulmonary embolism (blockage of the main artery of the lung or one of its branches by a blood clot that has travelled from elsewhere in the body through the bloodstream) • Aspiration pneumonia (lung infection that develops by breathing in foreign materials) • Breathing difficulty, possibly leading to death (1 to 2 in 10 cases are fatal) TRANSMISSION Tetanus is different from other vaccine-preventable diseases because it does not spread from person to person. -

Sporulation Evolution and Specialization in Bacillus

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473793; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Research article From root to tips: sporulation evolution and specialization in Bacillus subtilis and the intestinal pathogen Clostridioides difficile Paula Ramos-Silva1*, Mónica Serrano2, Adriano O. Henriques2 1Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência, Oeiras, Portugal 2Instituto de Tecnologia Química e Biológica, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Oeiras, Portugal *Corresponding author: Present address: Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Marine Biodiversity, Leiden, The Netherlands Phone: 0031 717519283 Email: [email protected] (Paula Ramos-Silva) Running title: Sporulation from root to tips Keywords: sporulation, bacterial genome evolution, horizontal gene transfer, taxon- specific genes, Bacillus subtilis, Clostridioides difficile 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473793; this version posted March 11, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. Abstract Bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum are able to enter a developmental pathway that culminates with the formation of a highly resistant, dormant spore. Spores allow environmental persistence, dissemination and for pathogens, are infection vehicles. In both the model Bacillus subtilis, an aerobic species, and in the intestinal pathogen Clostridioides difficile, an obligate anaerobe, sporulation mobilizes hundreds of genes. -

Tetanus: a Case Study

Tetanus: A Case Study Peter J. Raia, MS, MD J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as on 1 May 2001. Downloaded from Tetanus is a disease caused by the toxin produced raised 5-cm erythematous circumferential lesion by Clostridium tetani. The clostridium tetanus bac- with a centrally granulated 2.5 ϫ 1-cm puncture terium is ubiquitous, and as such, C tetani infection wound just lateral to the mid tibial aspect of his can be acquired through surgery, intravenous drug right leg. His leg was draped in sterile fashion. abuse, the neonate’s umbilicus, bites, burns, body Hydrogen peroxide was applied to the area and, 3 piercing, puncture wounds, and ear infections. In mL of 1% lidocaine was injected around the lesion. short, this organism can enter through any break in The wound was surgically de´brided of all necrotic the integrity of the body. As a result of widespread tissue and debris with a No. 15 scalpel and copi- vaccination, tetanus is relatively rare in the United ously irrigated with normal saline. A wick was in- States. Even so, there were 325 cases of tetanus serted for drainage, and the wound was allowed to reported between 1991 and 1997, or approximately drain and to close by secondary intention. 1 46.4 cases per year. The following case of tetanus The patient was counseled about the diagnosis is one of three reported by the New York State of tetanus with secondary wound infection and the Department of Health in 1999. need for hospital admission. The patient refused admission, so he was advised about all the possible Case Report sequelae of the disease including death. -

Virulence Plasmids of the Pathogenic Clostridia SARAH A

Virulence Plasmids of the Pathogenic Clostridia SARAH A. REVITT-MILLS, CALLUM J. VIDOR, THOMAS D. WATTS, DENA LYRAS, JULIAN I. ROOD, and VICKI ADAMS Infection and Immunity Program, Biomedicine Discovery Institute and Department of Microbiology, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia ABSTRACT The clostridia cause a spectrum of diseases in extrachromosomally. These toxins have diverse mecha- humans and animals ranging from life-threatening tetanus and nisms of action and include pore-forming cytotoxins, botulism, uterine infections, histotoxic infections and enteric phospholipases, metalloproteases, ADP-ribosyltransferases diseases, including antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and food and large glycosyltransferases. This review focuses on poisoning. The symptoms of all these diseases are the result of potent protein toxins produced by these organisms. These toxins these toxins and the elements that carry the toxin struc- are diverse, ranging from a multitude of pore-forming toxins tural genes. For ease of discussion it has been structured to phospholipases, metalloproteases, ADP-ribosyltransferases on a bacterial species-specific basis. and large glycosyltransferases. The location of the toxin genes is the unifying theme of this review because with one or two exceptions they are all located on plasmids or on bacteriophage PAENICLOSTRIDIUM (CLOSTRIDIUM) that replicate using a plasmid-like intermediate. Some of these SORDELLII plasmids are distantly related whilst others share little or no similarity. Many of these toxin plasmids have been shown to Virulence Properties of P. sordellii be conjugative. The mobile nature of these toxin genes gives Paeniclostridium (formerly Clostridium) sordellii causes a ready explanation of how clostridial toxin genes have been several severe diseases in both humans and animals. -

The Gram Positive Bacilli of Medical Importance Chapter 19

The Gram Positive Bacilli of Medical Importance Chapter 19 MCB 2010 Palm Beach State College Professor Tcherina Duncombe Medically Important Gram-Positive Bacilli 3 General Groups • Endospore-formers: Bacillus, Clostridium • Non-endospore- formers: Listeria • Irregular shaped and staining properties: Corynebacterium, Proprionibacterium, Mycobacterium, Actinomyces 3 General Characteristics Genus Bacillus • Gram-positive/endospore-forming, motile rods • Mostly saprobic • Aerobic/catalase positive • Versatile in degrading complex macromolecules • Source of antibiotics • Primary habitat:soil • 2 species of medical importance: – Bacillus anthracis right – Bacillus cereus left 4 Bacillus anthracis • Large, block-shaped rods • Central spores: develop under all conditions except in the living body • Virulence factors – polypeptide capsule/exotoxins • 3 types of anthrax: – cutaneous – spores enter through skin, black sore- eschar; least dangerous – pulmonary –inhalation of spores – gastrointestinal – ingested spores Treatment: penicillin, tetracycline Vaccines (phage 5 sensitive) 5 Bacillus cereus • Common airborne /dustborne; usual methods of disinfection/ antisepsis: ineffective • Grows in foods, spores survive cooking/ reheating • Ingestion of toxin-containing food causes nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea; 24 hour duration • No treatment • Increasingly reported in immunosuppressed article 6 Genus Clostridium • Gram-positive, spore-forming rods • Obligate Anaerobes • Catalase negative • Oval or spherical spores • Synthesize organic -

Chapter 19 the GramPositive Bacilli of Medical Importance

Foundations in Microbiology Fifth Edition Talaro Chapter 19 The GramPositive Bacilli of Medical Importance Chapter 19 2 3 4 Bacillus • grampositive, endosporeforming, motile rods • mostly saprobic • aerobic & catalase positive • versatile in degrading complex macromolecules • source of antibiotics • primary habitat is soil • 2 species of medical importance – Bacillus anthracis – Bacillus cereus 5 Bacillus anthracis • large, block shaped rods • central spores that develop under all conditions except in the living body • virulence factors – capsule & exotoxins • 3 types of anthrax – Cutaneous – spores enter through skin, black sore eschar; least dangerous – Pulmonary –inhalation of spores – Gastrointestinal – ingested spores • treated with penicillin or tetracycline • vaccine – toxoid 6X over 1.5 years; annual boosters 6 7 Bacillus cereus • common airborne & dustborne • grows in foods, spores survive cooking & reheating • ingestion of toxincontaining food causes nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps & diarrhea; 24 hour duration • no treatment • spores abundant in the environment 8 9 Clostridium • grampositive, sporeforming rods • anaerobic & catalase negative • 120 species • oval or spherical spores produced only under anaerobic conditions • synthesize organic acids & alcohols & exotoxins • cause wound & tissue infections & food intoxications 10 Clostridium perfringens • causes gas gangrene in damaged or dead tissues • 2 nd most common cause of food poisoning, worldwide • virulence factors – toxins – alpha toxin – causes RBC rupture, -

Regulation of Toxin Synthesis in Clostridium Botulinum and Clostridium Tetani Chloé Connan, Cécile Denève, Christelle Mazuet, Michel Popoff

Regulation of toxin synthesis in Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium tetani Chloé Connan, Cécile Denève, Christelle Mazuet, Michel Popoff To cite this version: Chloé Connan, Cécile Denève, Christelle Mazuet, Michel Popoff. Regulation of toxin synthesis in Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium tetani. Toxicon, Elsevier, 2013, 75 (3), pp.90 - 100. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2013.06.001. pasteur-01792396 HAL Id: pasteur-01792396 https://hal-pasteur.archives-ouvertes.fr/pasteur-01792396 Submitted on 1 Aug 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - ShareAlike| 4.0 International License 1 REGULATION OF TOXIN SYNTHESIS IN CLOSTRIDIUM BOTULINUM AND CLOSTRIDIUM TETANI Chloé CONNAN, Cécile DENÈVE, Christelle MAZUET, Michel R. POPOFF* Institut Pasteur, Unité des Bactéries Anaérobies et Toxines, Paris, France Key words: Clostridium botulinum, Clsotridfium tetani, botulinum neurotoxin, tetanus toxin, regulation Corresponding author Institut Pasteur, Unité des Bactéries Anaérobies et Toxines, 25 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris cedex15, France [email protected] 2 ABSTRACT Botulinum and tetanus neurotoxins are structurally and functionally related proteins that are potent inhibitors of neuroexocytosis. Botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT) associates with non-toxic proteins (ANTPs) to form complexes of various sizes, whereas tetanus toxin (TeNT) does not form any complex. -

Clostridial Diseases of Cattle and Sheep Frank Malone

Clostridial Diseases of Cattle and Sheep Frank Malone Disease Surveillance and Investigation Branch, Veterinary Sciences Division, Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, 43 Beltany Road, Coneywarren, Omagh, Co. Tyrone BT78 5NF, Northern Ireland (Text of a paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association of Veterinary Surgeons Practising in Northern Ireland, Enniskillen, October 2004) Introduction include C. chauvoei, the major cause The Clostridium species affecting of blackleg, and C. novyi type B, which cattle and sheep are large, Gram- causes black disease. positive, rod-shaped, spore-bearing bacteria. Many clostridia are Clostridia which produce enterotoxins saprophytes, which normally grow in C. perfringens species cause soil, water and decomposing plant and enterotoxaemia and enteropathy. animal material. Other species, such Examples include C. perfringens type as C. perfringens, are normal D, which causes pulpy kidney disease inhabitants of the intestines and, after and C. perfringens type B, which the death of the animal, rapidly invade causes lamb dysentery. the blood and tissues playing a major role in decomposing the carcass. There has been an increase in recent These post-mortem invaders must be years in submissions to DARD’s distinguished at post-mortem Veterinary Sciences Division (VSD) of examination from those organisms carcases affected by clostridial causing primary clostridial infections. diseases (Figure 1). Diseases Caused by Pathogenic Neurotrophic Clostridia Clostridia C. tetani Quinn and others (2000) divided the Tetanus occurs sporadically in cattle pathogenic clostridia affecting cattle and sheep of all ages. Tetanus and sheep into the following groups: endospores are present in the neurotrophic clostridia, histotoxic environment and may enter surgical clostridia and clostridia which produce wounds, such as after castration or enterotoxins (Table 1). -

Enhancement of Staphylococcus Aureus Infections in Mice by Viable Spores of Clostridium Tetani

Enhancement of Staphylococcus aureus infections in mice by viable spores of Clostridium tetani Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Drube, Clairmont George, 1928- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 17:54:47 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551975 ENHANCEMENT OF STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS INFECTIONS IN MICE BY VIABLE SPORES OF CLOSTRIDIUM TETANI by Clairmont George Drube A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND MEDICAL TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE . \ In the Graduate p©liege - THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1967 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted. in partial ful= fillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited■in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Libraryo Brief quotations from'this thesis are allowable without special permissions provided that accurate' acknowledgment of source is mad@0 Requests for permis™ sion for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may foe granted by the copyright holdere • ... SIGNED: APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: . JLz Lj /3 Wayburn ST%Ferer Dafe Professor o f ' Microbiology and Medical Technology ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to express his gratitude and appreciation to Dr„ Wayfourn S 0 Je’ter for cons true five eriticisms generous assistance and encouragement during this study® : . -

The Genome Sequence of Clostridium Tetani, the Causative Agent of Tetanus Disease

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Regensburg Publication Server The genome sequence of Clostridium tetani, the causative agent of tetanus disease Holger Bru¨ ggemann*, Sebastian Ba¨ umer*, Wolfgang Florian Fricke*, Arnim Wiezer*, Heiko Liesegang*, Iwona Decker*, Christina Herzberg†, Rosa Martı´nez-Arias*, Rainer Merkl*, Anke Henne*, and Gerhard Gottschalk*†‡ *Go¨ ttingen Genomics Laboratory and †Department of General Microbiology, Institute of Microbiology and Genetics, Georg-August-University, Grisebachstrasse 8, D-37077 Go¨ ttingen, Germany Edited by Dieter So¨ ll, Yale University, New Haven, CT, and approved December 11, 2002 (received for review September 27, 2002) Tetanus disease is one of the most dramatic and globally prevalent a mammalian host. The presented information may also help to diseases of humans and vertebrate animals, and has been reported unravel the regulatory network governing tetanus toxin forma- for over 24 centuries. The manifestation of the disease, spastic tion, which is still poorly understood (11). paralysis, is caused by the second most poisonous substance known, the tetanus toxin, with a human lethal dose of Ϸ1ng͞kg. Methods Fortunately, this disease is successfully controlled through immu- Sequencing Strategy. Genomic DNA of C. tetani E88, a nonsporu- nization with tetanus toxoid; nevertheless, according to the World lating variant of strain Massachusetts used in vaccine production, Health Organization, an estimated 400,000 cases still occur each was extracted and sheared randomly. Several shotgun libraries year, mainly of neonatal tetanus. The causative agent of tetanus were constructed by using size fractions ranging from 1 to 3 kb. -

Clostridium Clostridium Is a Genus of Gram-Positive Bacteria. They Are

Clostridium Clostridium is a genus of Gram-positive bacteria. They are obligate anaerobes capable of producing endospores.[1][2] Individual cells are rod- shaped, which gives them their name, from the Greek kloster or spindle. These characteristics traditionally defined the genus, however many species originally classified as Clostridium have been reclassified in other genera. Overview Clostridium consists of around 100 species[3] that include common free- living bacteria as well as important pathogens.[4] There are five main species responsible for disease in humans: C. botulinum, an organism that produces botulinum toxin in food/wound and can cause botulism.[5]Honey sometimes contains spores of Clostridium botulinum, which may cause infant botulism in humans one year old and younger. The toxin eventually paralyzes the infant's breathing muscles.[6] Adults and older children can eat honey safely, because Clostridium do not compete well with the other rapidly growing bacteria present in the gastrointestinal tract. This same toxin is known as "Botox" and is used cosmetically to paralyze facial muscles to reduce the signs of aging; it also has numerous therapeutic uses. C. difficile, which can flourish when other bacteria in the gut are killed during antibiotic therapy, leading to pseudomembranous colitis (a cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea).[7] C. perfringens, formerly called C. welchii, causes a wide range of symptoms, from food poisoning to gas gangrene. Also responsible for enterotoxemia in sheep and goats.[8]C. perfringens also takes the place Dr. Wahidah H. alqahtani of yeast in the making of salt rising bread. The name perfringens means 'breaking through' or 'breaking in pieces'. -

Clostridium Bacteria

Lec (01) Medical Microbiology Dr. Marwa Kadhim Clostridium Bacteria Introduction: The genus Clostridium includes all anaerobic, gram-positive bacilli and capable of forming endospores. Spores of clostridia are usually wider than the diameter of the rods in which they are formed, giving the bacillus a swollen appearance resembling a spindle. The name Clostridium is derived from the word „Kloster‟ (meaning a spindle). General features of Clostridium: 1. Morphology The clostridia are 1) gram-positive typically large, 2) straight or slightly curved rods, 3-8 × 0.6-1 μm with slightly rounded ends. Gram-positive, pleomorphism forms are common. 3) Most species of clostridia are motile with peritrichous flagella except Cl. perfringens and Cl. tetani type VI which are non-motile. All clostridia are non-capsulated with the exception of Cl. perfringens. All clostridia produce endospores. Spores of clostridia are usually wider than the diameter of the rods in which they are formed. In the various species, the spore is placed centrally, sub-terminally, or terminally. 2. Culture Most species are obligate anaerobes. A few species grow in the presence of trace amounts of air and some actually grow slowly under normal atmospheric conditions. Clostridia grow on enriched media in the presence of reducing agent such as cysteine or thioglycollate (to maintain a low oxidation-reduction potential) Liquid media like cooked meat broth (CMB) or thioglycollate media (containing reducing agent thioglycollate and 0.1% agar) are very useful for growing clostridia. A very useful medium is Robertson‟s cooked (RCM) meat broth. It contains unsaturated fatty acids which take up oxygen.