New Final Rec 5 Cover.Tif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Jargon Society]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3505/jargon-society-283505.webp)

[Jargon Society]

OCCASIONAL LIST / BOSTON BOOK FAIR / NOV. 13-15, 2009 JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS 790 Madison Ave, Suite 605 New York, New York 10065 Tel 212-988-8042 Fax 212-988-8044 Email: [email protected] Please visit our website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers These and other books will be available in Booth 314. It is advisable to place any orders during the fair by calling us at 610-637-3531. All books and manuscripts are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. ALGREN, Nelson. Somebody in Boots. 8vo, original terracotta cloth, dust jacket. N.Y.: The Vanguard Press, (1935). First edition of Algren’s rare first book which served as the genesis for A Walk on the Wild Side (1956). Signed by Algren on the title page and additionally inscribed by him at a later date (1978) on the front free endpaper: “For Christine and Robert Liska from Nelson Algren June 1978”. Algren has incorporated a drawing of a cat in his inscription. Nelson Ahlgren Abraham was born in Detroit in 1909, and later adopted a modified form of his Swedish grandfather’s name. He grew up in Chicago, and earned a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign in 1931. In 1933, he moved to Texas to find work, and began his literary career living in a derelict gas station. A short story, “So Help Me”, was accepted by Story magazine and led to an advance of $100.00 for his first book. -

Late Modernist Poetics and George Schneeman's Collaborations with the New York School Poets

Timothy Keane Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 1, No 2 (2014) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 No Real Assurances: Late Modernist Poetics and George Schneeman’s Collaborations with the New York School Poets Timothy Keane City University of New York Abstract: Painter George Schneeman’s collaborations with the New York School poets represent an under-examined, vast body of visual-textual hybrids that resolve challenges to mid-and-late century American art through an indirect alliance with late modernist literary practices. Schneeman worked with New York poets intermittently from 1966 into the early 2000s. This article examines these collagist works from a formalist perspective, uncovering how they incorporate gestural techniques of abstract art and the poetic use of juxtaposition, vortices, analogies, and pictorial and lexical imagism to generate non-representational, enigmatic assemblages. I argue that these late modernist works represent an authentically experimental form, violating boundaries between art and writing, disrupting the venerated concept of single authorship, and resisting the demands of the marketplace by affirming for their creators a unity between art-making and daily life—ambitions that have underpinned every twentieth century avant-garde movement. On first seeing George Schneeman’s painting in the 1960s, poet Alice Notley asked herself, “Is this [art] new? Or old fashioned?”1 Notley was probably reacting to Schneeman’s unassuming, intimate representations of Tuscan landscape and what she called their “privacy of relationship.” The potential newness Notley detected in Schneeman’s “old-fashioned” art might be explained by how his small-scale and quiet paintings share none of the self-conscious flamboyance in much American painting of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Part of His History 1944-2020 by Steve Clay Originally Published in the Brooklyn Rail Dec 20 – Jan 21, 2021 Issue

IN MEMORIAM Lewis Warsh: Part of His History 1944-2020 By Steve Clay Originally published in The Brooklyn Rail Dec 20 – Jan 21, 2021 Issue Working with Lewis Warsh was always an effortless pleasure and indistinguishable from our friendship. I first met him in Brooklyn in 1995, introduced by Mitch Highfill. We spoke about his archive and collection of rare books he wanted to sell, and arranged to meet at his apartment. During that visit I looked at his treasures, among which was a small book he'd assembled by hand when he found a set of black and white photographs taken in 1968, primarily on Bustin's Island, Maine and in Bolinas, California. The photographs were classic family-style vacation snapshots of Lewis and Anne Waldman, Ted, Sandy, and Kate Berrigan, Tom, Angelica, and baby Juliet Clark, Joanne Kyger, Jack Boyce, and others. Lewis had mounted the photos into a store- bought hardcover photo book, then typed captions and placed them across from the pictures: The front cover read Bustin's Island '68. I immediately proposed that Granary Books publish Portrait of Lewis Warsh, pencil on paper by Phong H. Bui. an edition. I was impressed with the spontaneity of the photographs and the sincerity of the writing. They gave me a private glimpse into a community of poets whose work and stories I knew but was now seeing in their formative years as friends and collaborators. It's a remarkably lucid portrait of a time and place. The captions, written 28 years after the fact, brought perspective to the changes during the intervening years. -

Rare Books and First Editions R R Manuscripts and Letters R Literary

Rare Books and First Editions R JamEs s. Jaffe R manuscripts and Letters R Rare Books Literary art and Photography R Rare Books & First Editions manuscripts & Letters Literary art & Photography James S. Jaffe Rare Books New York Item 1: Culin, stewart. Primitive Negro Art, 1923 [aFRICaN aRT] CULIN, stewart. Primitive Negro Art, Chiefly 1 from the Belgian Congo. 8vo, 42 pages, illustrated with 8 plates, origi- nal black, green & yellow printed wrappers. Brooklyn: Brooklyn mu- all items are offered subject to prior sale. seum, 1923. First edition of the first major exhibition of african art all books and manuscripts have been carefully described; however, any in america. In 1903, stewart Culin (1858–1929) became the found- item is understood to be sent on approval and may be returned within sev- ing curator of the Department of Ethnology at the museum of the en days of receipt for any reason provided prior notification has been given. Brooklyn Institute of arts and sciences, now the Brooklyn museum. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. He was among the first museum curators to display ethnological col- lections as art objects, not as ethnographic specimens, and among the We accept Visa, masterCard and american Express. first to recognize museum installation as an art form in its own right. New York residents must pay appropriate sales tax. Culin’s exhibition of Primitive Negro Art, based in large part on his own We will be happy to provide prospective customers with digital images of collection which became in turn the basis for the Brooklyn museum’s items in this catalogue. -

James Hoff and Danny Snelson

Inventory Arousal James Hoff and Danny Snelson A lecture by James Hoff at the National Academy of Art, Oslo, Norway on February 11, 2008. Transcribed in real time by Danny Snelson in Tokyo, Japan. Introduction by Danny Snelson In the winter of 2007, James Hoff contacted me to transcribe a lecture he would be giving on minor histories as primary information—or rather, on secondary information as source material for primary history—in Oslo, Norway. In the spirit of collaboration, I took this offer as an opportunity to experiment in performative editing & live data processing. The process of this transcription I undertook was simple. First, I received a large list of key figures, publications and works James might address. His lecture was improvisational, based on hundreds of images and hours of artists’ curated video running simultaneously and connected anecdotally, so there was no set agenda or instructions for the material that would or wouldn’t be used. Over the next couple of months, I googled together a massive body of text around this list (from the various virtual resources available to me online in Japan). The sources ran from book reviews to artist interviews, from essays, memoirs and stock lists to articles, blog posts and even full length books: what- ever was searchable & citable, informative or interesting. We then arranged for Børre Saethre, a Norwegian artist, to relay the lec- ture via Skype telephony to my computer in Tokyo. Taking James’ words from this digital transmission, I culled paragraphs from my previously complied text file using the “find,” “copy” & “paste” functions of my TextEdit program. -

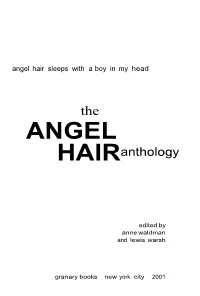

Introduction

angel hair sleeps with a boy in my head the ANGEL anthology HAIR edited by anne waldman and lewis warsh granary books new york city 2001 INTRODUCTION ANNE WALDMAN I met Lewis Warsh at the Berkeley Poetry Conference and will always forever after think we founded Angel Hair within that auspicious moment. Conflation of time triggered by romance adjacent to the glam• orous history-making events of the confer• ence seems a reasonable explanation. Perhaps Angel Hair was what we made together in our brief substantive marriage that lasted and had repercussions. And sped INTRODUCTION us on our way as writers. Aspirations to be a poet were rising, the ante grew higher at LEWIS WARSH Berkeley surrounded by heroic figures of the New American Poetry. Here was a fellow Anne Waldman and I met in the earliest New Yorker, same age, who had also written stages of our becoming poets. Possibly edit• novels, was resolute, erudite about contem• ing a magazine is a tricky idea under these porary poetry. Mutual recognition lit us up. circumstances. Possibly it's the best idea-to Don't I know you? test one's ideas before you even have them, Summer before last year at Bennington or when they're pre-embryonic. In a sense where I'd been editing SILO magazine doing a magazine at this early moment was under tutalage of printer-poet Claude our way of giving birth-as much to the Fredericks, studying literature and poetry actual magazine and books as to our selves as with Howard Nemerov and other literary poets. -

$5.00 #219 April-JUNE 2009 New Poetry from Coffee House Press

$5.00 #219 APRIL-JUNE 2009 New Poetry from Coffee House Press Portrait and A Toast in Dream: the House New and of Friends Selected Poems POEMS BY BY BILL BERKSON AKILAH OLIVER ISBN: 978-1-56689-229-2 ISBN: 978-1-56689-222-3 The major work from Bill Berkson, “a “A Toast in the House of Friends brings us serene master of the syntactical sleight and back to life via the world of death and transformer of the mundane into the dream . Akilah Oliver’s book is an miraculous.” (Publishers Weekly) extraordinary gift for everyone.” —Alice Notley Coal Mountain The Spoils Elementary POEMS BY POEMS BY TED MATHYS MARK NOWAK WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY IAN TEH ISBN: 978-1-56689-228-5 ISBN: 978-1-56689-230-8 “A tribute to miners and working people “Reading Mathys, one remembers that everywhere . [Coal Mountain Elementary] poetry isn’t a dalliance, but a way of sorting manages, in photos and in words, to por- through life-or-death situations.” tray an entire culture.” —Howard Zinn —Los Angeles Times � C O M I N G S O O N � Beats at Naropa, an anthology edited by Anne Waldman and Laura Wright Poetry from Edward Sanders, Adrian Castro, Mark McMorris, and Sarah O’Brien Good books are brewing at www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #219 april-june 2009 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. -

Postmodernism, Lyricism, and Queer Aesthetics in 1970S New York Poetry

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2017 Cold War New York: Postmodernism, Lyricism, And Queer Aesthetics In 1970s New York Poetry Jared James O'Connor University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Connor, Jared James, "Cold War New York: Postmodernism, Lyricism, And Queer Aesthetics In 1970s New York Poetry" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 991. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/991 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLD WAR NEW YORK: POSTMODERNISM, LYRICISM, AND QUEER AESTHETICS IN 1970S NEW YORK POETRY A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for a degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by JARED J. O'CONNOR May 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Jared O'Connor ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This thesis explores the poetry of Joe Brainard and Anne Waldman, two poets of the critically neglected Second-Generation New York School. I argue that Brainard and Waldman help define the emerging discourse of postmodern poetry through their attention to Cold War culture of the 1970s, countercultural ideologies, and poetic form. Both Brainard and Waldman enact a poetics of vulnerability in their work, situating themsleves as wholly unique from their late-modernist predecessors. In doing so, they help engender a poetics concerned not only with the intellectual stakes but with the cultural environment they are forced to navigate. -

Introduction

25927_ch01.qxd 7/14/05 8:39 AM Page 1 Introduction I heard Ted say more than once that his collected poems should be like a collected books. But he didn’t always work in sequences, and he wasn’t always consciously in the process of writing a book. He wrote many individual poems, and he sometimes seemed to write purely for fun. As for publication, publishers would approach him for a book without knowing exactly what he had, and sometimes it didn’t seem to him as if he had that much. If there was a sequence ready, or a book in a unified style like Many Happy Returns, certainly he published that. If he had a stack of dissimilar works or if he didn’t even know what he had, he still set about the process of con- structing a “book.” He loved to make things out of pieces, often ones that didn’t fit to- gether conventionally. A book was like a larger poem that could be as much “made” out of what was at hand, as “written” in a continuous way out of a driving idea. This volume is an attempt to be a collected books, but it can’t be that precisely and so isn’t called The Collected Books. Though Ted wrote sequences and con- structed books, he didn’t produce a linear succession of discrete, tidy volumes. He perceived time as overlapping and circular; the past was always alive and relevant, and a particular poem might be as repeatable as an individual line or phrase was for him from the time of the composition of The Sonnets onward. -

Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan

The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Humanities Endowment Fund of the University of California Press Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous support of Jamie and David Wolf and the Rosenthal Family Foundation as members of the Publisher’s Circle of the University of California Press Foundation. The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan Edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press, one of the most distinguished univer- sity presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2011 by The Regents of the University of California Poems from The Sonnetsby Ted Berrigan, copyright © 2000 by Alice Notley, Literary Executrix of the Estate of Ted Berrigan. Used by per- mission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Berrigan, Ted. [Poems. Selections] The selected poems of Ted Berrigan / edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn: 978-0-520-26683-4 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn: 978-0-520-26684-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Notley, Alice 1945– II. Berrigan, Anselm. III. Berrigan, Edmund, 1974– IV. Title. -

Poetry Reading Flyers of the Mimeograph Revolution

Poetry Reading Flyers of the Mimeograph Revolution Poetry reading flyers are transitory by nature — quickly printed, locally distributed, easily discarded and thus frequently overlooked by scholars and curators when researching and documenting literary activities. They appear from time to time as fleeting one-offs in archives and collections, yet when viewed in the context of a large group these seemingly ephemeral objects take on significance as primary documents. Through close observation of this collection of poetry reading flyers, one gains insight into considerations of the development and representation of literary communities and affiliations of poets, the interplay of visual image, text and design, and the evolution of printing technology. A great many of the flyers appeared during the flowering of the mimeo revolution, an extraordinarily rich period of literary activity which was in part characterized by a profusion of poetry readings, performances, and publications documented by the flyers. This collection includes flyers from the mid-sixties to the present with a focus on the seventies, and embraces a range of poets and national venues with particular attention to activity in New York City and the San Francisco Bay Area. For a reading by Lewis Warsh and Harris Schiff, Ear Inn, New York City, December 6, n.d. Flyer. 11 x 8-1/2 inches. There are approximately 400 flyers (including a smattering of posters and cards), which are often 8 ½ x 11 – 8 ½ x 17 inches and printed as cheaply as possible, frequently via mimeograph, and often intended to be mailed. More than 250 writers and artists and nearly 100 venues are represented with a strong concentration on the Poetry Project at St. -

The Art of Collaboration: Poets, Artists, Books

THE ART OF COLLABORATION POETS, ARTISTS, BOOKS edited by Anca Cristofovici & Barbara Montefalcone CUNEIFORM PRESS • 2015 CONTENTS Editors’ Note page 9 OPENING Unfolding Possibilities: Artists’ Books, Cultural Patterns, Forms of Experience 11 ANCA CRISTOFOVICI ELECTIVE AFFINITIES, EFFECTIVE DIRECTIONS ‘Poetry is a team sport’: Some Considerations on Poetry, Collaboration and the Book 23 BARBARA MONTEFALCONE Charles Bernstein De/Signs, or Severe Typo’s Ambiguity 33 ANTOINE CAZÉ Et moi je ne suis pas peintre! Why Frank O’Hara Is Not a Painter 41 OLIVIER BROSSARD ARTISTIC COMMUNITIES AND CREATIVE COLLABORATION The Bauhaus and Its Media: From the Artists’ Book to the Bauhaus Journal 51 MICHAEL SIEBENBRODT Artists’ Books at Black Mountain College: Taking Control of the Means of Production 57 VINCENT KATZ POETS AND ARTISTS AT WORK Hands On/ Hands Off 69 BILL BERKSON Working With Others: Trials and Chemistry in Book Form 81 VINCENT KATZ On My Collaborations 91 SUSAN BEE Catalogues and Collaborations 99 RAPHAEL RUBINSTEIN INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS AND THE MAKING OF ARTISTS’ BOOKS 109 Global Books: New Aspects in the Making of Artists’ Books GERVAIS JASSAUD 119 contrat maint: A Co-Elaboration PASCAL POYET & FRANÇOISE GORIA 131 The Editor at Work: Artists’ Books and New Technologies KYLE SCHLESINGER KEEPING AND SHOWING 145 Artists’ Books in the Rare Books Reserve at the Bibliohthèque Nationale de France: The Origins and Extension of a Collection ANTOINE CORON 159 Some Thoughts on the Types and Display of Collaborative and Artists’ Books in the San Francisco Bay Area CONSTANCE LEWALLEN POETRY IN SPACE 167 Reading Red CHARLES BERNSTEIN & RICHARD TUTTLE User’s Note ANCA CRISTOFOVICI 171 Notes 189 About the Authors while emphasizing the value of a cheaper and portable book format.