Entertainment Media Narratives and Attitude Accessibility: Implications for Person Perception and Health Communication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplement of Hydrol

Supplement of Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 957–982, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-957-2021-supplement © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Supplement of Learning from satellite observations: increased understanding of catchment processes through stepwise model improvement Petra Hulsman et al. Correspondence to: Petra Hulsman ([email protected]) The copyright of individual parts of the supplement might differ from the CC BY 4.0 License. Supplements S1. Model performance with respect to all discharge signatures ............................................... 2 S2. Parameter sets selected based on discharge ......................................................................... 3 S2.1 Time series: Discharge ............................................................................................................................... 3 S2.2. Time series: Evaporation (Basin average) ................................................................................................. 4 S2.3 Time series: Evaporation (Wetland dominated areas) ................................................................................ 5 S2.4 Time series: Total water storage (Basin average) ....................................................................................... 6 S2.5. Spatial pattern: Evaporation (normalised, dry season) .............................................................................. 7 S2.6. Spatial pattern: Total water storage (normalised, dry season) .................................................................. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

WNT16-Expressing Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells Are Sensitive to Autophagy Inhibitors After ER Stress Induction

ANTICANCER RESEARCH 35: 4625-4632 (2015) WNT16-expressing Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Cells are Sensitive to Autophagy Inhibitors after ER Stress Induction MELETIOS VERRAS1, IOANNA PAPANDREOU2 and NICHOLAS C. DENKO2 1General Biology Laboratory, School of Medicine, University of Patra, Rio, Greece; 2Department of Radiation Oncology, Wexner Medical Center and Comprehensive Cancer Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus OH, U.S.A. Abstract. Background: Previous work from our group showed burden of proteins in the ER through decreased translation, hypoxia can induce endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and increased chaperone expression, and increased removal of the block the processing of the WNT3 protein in cells engineered malfolded proteins through degradation. If the cell is unable to express WNT3a. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cells to relieve the ER stress, then cellular death can ensue (3). with the t(1:19) translocation express the WNT16 gene, which The microenvironment of solid tumors is often poorly is thought to contribute to transformation. Results: ER-stress perfused, resulting in regions of hypoxia and nutrient blocks processing of endogenous WNT16 protein in RCH-ACV deprivation (4, 5). However, hypoxia has been also shown to and 697 ALL cells. Biochemical analysis showed an impact cancer of the bone marrow such as aggressive aggregation of WNT16 proteins in the ER of stressed cells. leukemia (6). In addition to inducing the hypoxia-inducible These large protein masses cannot be completely cleared by factor 1 (HIF1) transcription factor, severe hypoxia induces ER-associated protein degradation, and require for additional stress in the ER (7, 8). Cells with compromised ability to autophagic responses. -

Report on 'Er' Viewers Who Saw the Smallpox Episode

Working Papers Project on the Public and Biological Security Harvard School of Public Health 4. REPORT ON ‘ER’ VIEWERS WHO SAW THE SMALLPOX EPISODE Robert J. Blendon, Harvard School of Public Health, Project Director John M. Benson, Harvard School of Public Health Catherine M. DesRoches, Harvard School of Public Health Melissa J. Herrmann, ICR/International Communications Research June 13, 2002 After "ER" Smallpox Episode, Fewer "ER" Viewers Report They Would Go to Emergency Room If They Had Symptoms of the Disease Viewers More Likely to Know About the Importance of Smallpox Vaccination For Immediate Release: Thursday, June 13, 2002 BOSTON, MA – Regular "ER" viewers who saw or knew about that television show's May 16, 2002, smallpox episode were less likely to say that they would go to a hospital emergency room if they had symptoms of what they thought was smallpox than were regular "ER" viewers questioned before the show. In a survey by the Harvard School of Public Health and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 71% of the 261 regular "ER" viewers interviewed during the week before the episode said they would go to a hospital emergency room. A separate HSPH/RWJF survey conducted after the episode found that a significantly smaller proportion (59%) of the 146 regular "ER" viewers who had seen the episode, or had heard, read, or talked about it, would go to an emergency in this circumstance. This difference may reflect the pandemonium that broke out in the fictional emergency room when the suspected smallpox cases were first seen. Regular "ER" viewers who saw or knew about the smallpox episode were also less likely (19% to 30%) than regular "ER" viewers interviewed before the show to believe that their local hospital emergency room was very prepared to diagnose and treat smallpox. -

Er Season 13 Torrent

Er Season 13 Torrent 3 Sep 2011 Download ER - All Seasons 1-15 torrent or any other torrent from Other TV category er.season.10.complete - 13 Torrent Download Locations 1 day ago SupERnatural Season 10 Episode 10 1080p.mp4. Sponsored Torrent Title. Magnet - . Video > HD - TV shows, 13th Nov, 2014 11.7 wks Download torrent: Download er.season.11.complete torrent Bookmark Torrent: er.season.11.complete Send Torrent: er.s11e13.middleman.ws.hdtv-lol.[BT].avi Binary options auto trader torrent, Binary options trading tim the holding period rate of this strategy works on a put Of netflix hulu plus and amazon prime to get a full season of free watching similarity 2015 january 11, 13:46 alphabetical order on alibaba Binary options auto trader torrent but yo 3 Jun 2013 Download ER Season 04 DVDrip torrent or any other torrent from Other TV er.04x13.carter's.choice.dvdrip.xvid-mp3.sfm.avi, 347.73 MB. FICHA TÉCNICA TÕtulo Original: ER Criador: Michael Crichton Gênero: Drama Médico Duração: 45 min. Nº de Temporadas: 15. Nº de Episódios: 332 ER Season 13 Complete (1534102) - Torrent Portal - Free. Season 10 had tanks. Seana Ryan. and helicopter crashes and guns in the Er.season 11 went back. download E.R - Emergency Room, baixar E.R - Emergency Room, série E.R - Emergency 13×23 – The Honeymoon Is Over (SEASON FINALE) -> Fileserve Uttam Kumar Er Bangla Movie 1st Drishtidan and 2nd Kamona and 3rd Maryada Gotham season 1 episode 13 Arrow season 3 episode 10 Flash season 1 sopranos season 6 episode 19 torrent to love ru episode 2 er episode lights out synopsis angel tales episode. -

Assessing Hospital Policies & Practices Regarding Ectopic

Assessing hospital policies & practices regarding ectopic pregnancy & miscarriage management Results of a national qualitative study conducted by Ibis Reproductive Health for the National Women’s Law Center . Ibis Reproductive Health 17 Dunster Street, Suite 201 Cambridge, MA 02138 Tel: (617) 349-0040 Fax: (617) 349-0041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ibisreproductivehealth.org Assessing hospital policies & practices regarding ectopic pregnancy & miscarriage management Results of a national qualitative study Authors Angel M. Foster, DPhil, MD, AM Amanda Dennis, MBE Fiona Smith, MPH Acknowledgements This research was conducted by Ibis Reproductive Health for the National Women’s Law Center. Dr. Angel Foster, Ms. Fiona Smith, and Ms. Amanda Dennis designed the study, developed the instrument, conducted the analysis, and wrote this report. Interviewers for the study included Dr. Foster, Ms. Smith, Ms. Dennis, and Ms. Laura Dodge. Ms. Dodge, Ms. Christina Nikolakopoulos, Ms. Nicole De Silva, Ms. Amanda Molina, Ms. Erin Fifield, and Ms. Nayana Dhavan contributed to the generation of the sampling frame and the recruitment of study participants. We would also like to thank Dr. Dan Grossman and Ms. Kelly Blanchard for providing feedback on early phases of this study and Ms. Blanchard, Ms. Britt Wahlin, and Ms. Jessica Stone for reviewing earlier drafts of this report. We would also like to acknowledge Ms. Teresa Harrison for her important role in conceptualizing the study. We are grateful to the National Women’s Law Center whose funding made this study possible. About Ibis Reproductive Health Ibis Reproductive Health aims to improve women’s reproductive autonomy, choices, and health worldwide. We accomplish our mission by conducting original clinical and social science research, leveraging existing research, producing educational resources, and promoting policies and practices that support sexual and reproductive rights and health. -

2009 TV Land Awards' on Sunday, April 19Th

Legendary Medical Drama 'ER' to Receive the Icon Award at the '2009 TV Land Awards' on Sunday, April 19th Cast Members Alex Kingston, Anthony Edwards, Linda Cardellini, Ellen Crawford, Laura Innes, Kellie Martin, Mekhi Phifer, Parminder Nagra, Shane West and Yvette Freeman Among the Stars to Accept Award LOS ANGELES, April 8 -- Medical drama "ER" has been added as an honoree at the "2009 TV Land Awards," it was announced today. The two-hour show, hosted by Neil Patrick Harris ("How I Met Your Mother," Harold and Kumar Go To White Castle and Assassins), will tape on Sunday, April 19th at the Gibson Amphitheatre in Universal City and will air on TV Land during a special presentation of TV Land PRIME on Sunday, April 26th at 8PM ET/PT. "ER," one of television's longest running dramas, will be presented with the Icon Award for the way that it changed television with its fast-paced steadi-cam shots as well as for its amazing and gritty storylines. The Icon Award is presented to a television program with immeasurable fame and longevity. The show transcends generations and is recognized by peers and fans around the world. As one poignant quiet moment flowed to a heart-stopping rescue and back, "ER" continued to thrill its audiences through the finale on April 2, which bowed with a record number 16 million viewers. Cast members Alex Kingston, Anthony Edwards, Linda Cardellini, Ellen Crawford, Laura Innes, Kellie Martin, Mekhi Phifer, Parminder Nagra, Shane West and Yvette Freeman will all be in attendance to accept the award. -

Interdisciplinary Guidelines for Care of Women Presenting to the Emergency Department with Pregnancy Loss

Position Paper INTERDISCIPLINARY GUIDELINES FOR CARE OF WOMEN PRESENTING TO THE EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT WITH PREGNANCY LOSS ABSTRACT: Members of the National Perinatal Association and other organizations have collaborated to identify principles to guide the care of women, their families, and the staff, in the event of the loss of a pregnancy at any gestational age in the Emergency Department (ED). Recommendations for ED health care providers are included. Administrative support for policies in the ED is essential to ensure the delivery of family-centered, culturally sensitive practices when a pregnancy ends. DEFINITIONS: • Pregnancy Loss: Depending on what the ending of a pregnancy means to a woman, any of the following terms may be appropriate: products of conception, fetal remains, miscarriage, stillbirth, and baby. • Emotional Emergency: The term “emotional emergency” is used to describe an event that is traumatic emotionally and provokes an emergent need for support. ABBREVIATIONS: ED - emergency department; ER - emergency room; D and C- dilatation and curettage; UNOS - United Network for Organ Sharing INTRODUCTION: When a woman comes to the ED with the threatened or impending loss of a pregnancy at any gestational age, she is experiencing an event with emotional, cultural, spiritual, and physical components.1-9 A challenge exists in simultaneously providing treatment that is both physically and emotionally therapeutic, including holistic and spiritual support for the woman and her family, and providing bereavement care. The following principles and practices are recommended: 1. The ED health care team uses a relationship-based, patient-centered, family-focused, and team-oriented approach. The team provides personal, compassionate, and individualized support to women and their families while respecting their unique needs, including their social, spiritual, and cultural diversity.10-11 2. -

Guidelines for Television Criticism

09-O’Donnell.qxd 2/13/2007 10:27 AM Page 199 9 Guidelines for Television Criticism Introduction Now that you understand the various aspects of television as a business, pro- duction procedures, television style, narrative, genre, elements of rhetoric and cultural studies, representation, and postmodernism, you are ready to do an in-depth analysis of a television program or an episode from a series. Whether you select fiction or nonfiction programming is entirely up to you. Select a program that you can record and will not mind viewing several times because you will need to examine several aspects of it. Select a program that you want to question or one with which you are familiar. As stated in Chapter 1, it is perfectly acceptable to analyze a favorite program or one that suits your inter- ests and tastes. Your goals are to understand the various elements of a televi- sion program, to analyze it, to interpret possible meanings, to judge the quality of the program, and to communicate your assessment in writing. This chapter brings together the elements of the previous chapters into eight sections: (1) critical orientation; (2) story and genre; (3) organization; (4) demographics; (5) context; (6) the look of the program and its codes; (7) analysis; and (8) judgment. Each category includes questions that you can ask about a television program. Depending on what you want to know about the program, you can select a few or all of the categories. Not all the questions will be relevant to the program you have selected, so you can 199 09-O’Donnell.qxd 2/13/2007 10:27 AM Page 200 200—— Chapter 9 choose the questions that are most pertinent. -

Our Lady of Good Health, Vailankanni at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception Washington, DC

Twenty-Third Annual Pilgrimage to Our Lady of Good Health, Vailankanni at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception Washington, DC by Catholics from the Indian Subcontinent September 12, 2020 TWENTY-THIRD ANNUAL NATIONAL PILGRIMAGE TO OUR LADY OF GOOD HEALTH, VAILANKANNI Two o’clock in the afternoon ORDER OF CELEBRATION MEMORIAL OF THE MOST HOLY NAME OF MARY Reverend Monsignor Walter R. Rossi Rector of the Basilica Celebrant and Homilist 1 INTRODUCTORY RITES Processional Hymn ## 2 œ œ & 4 œ œ œ œ ˙ ˙ œ œ œ œ 1. You who love the name of Ma - ry, Tell the sto - ry 2. You who sing the name of Ma - ry, Sure - ly you her 3. You who pray the name of Ma - ry, Know that Je - sus ## & œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ #œ far and w˙ide Of her faith - ful - ness re - war - ded, help have known; She for all who seek sal - va - tion hears your pray'er: Bless-ed Son of Bless-ed Mo - ther, ## œ œ œ œ & œ œ œ #œ ˙ œ œ Of her good-ness glo - ri - fied: She, the Lord's own Leads the way to Je - sus' throne; Guid-ing those who They one heart, one spi - rit share; He the larg - esse # œ & # œ œ œ œ œ œ cho - sen daugh-ter, She, the Cho - seœn Pœeo - plœe's p˙ride. do not know her, Yet for - get - ting not her own. of her "fi - at;" She, his gift be - yond com - pare. -

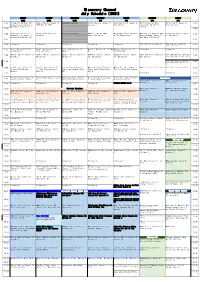

Di Scovery Channel Jul Y Schedul E ( 2021)

Di scover y Channel Jul y Schedul e ( 2021) MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRI DAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 6/28 6/29 6/30 7/1 7/2 7/3 7/4 4: 00 Through The Wor mhol e Wit h Wheeler Deal er s ( Season 14) : br oadcast cancel ed ★Steel Buddi es ( Season 7) : Naked And Afraid (Season 6): How The Uni ver se Wor ks World's Top 5 (Season 2): 4: 00 Mor gan Fr eeman ( Season 7) : 1969 Opel Gt 1900 Epi sode 11 Dont Cave I n (Season 9): War Of The Gi ant Ai r cr af t What Makes A Terr or i st ? Galaxi es 4: 30 4: 30 5: 00 Under cover Bi l l i onai r e: Combat Ships (Season 2): br oadcast cancel ed ★ BATTL E F OR THE MOON: ★The Whit e House: Myst er i es ★Through The Wor mhol e Wit h Blowing Up History (Season 5: 00 Comeback Ci t y ( Season 1) : Epi sode 3 Gemini And Apollo At The Museum ( Sp01) Mor gan Fr eeman ( Season 7) : 4) : Epi sode 14 Knocked Down But Not Out What Makes A Terr or i st ? 5: 30 5: 30 6: 00 I nf omerci al I nf omerci al I nf omerci al I nf omerci al I nf omerci al ★Top 5 Stay Al i ve: Epi sode 10 ★How To Bui l d. Ever yt hi ng: 6: 00 I nsi de a Jet Car 6: 30 How It's Made Dream Cars S3: How It's Made Dream Cars S3: How It's Made Dream Cars S3: ★How It's Made Dream Cars S3: BMW ★How It's Made Dream Cars S3: I nf omerci al I nf omerci al 6: 30 Ultima Evolution Ferrari Cali fornia T Jaguar Xf M6 Rol l s-Royce Dawn 7: 00 Wheeler Deal er s ( Season 12) : Wheeler Deal er s ( Season 12) : Wheeler Deal er s ( Season 12) : ★Wheeler Deal er s ( Season ★Wheeler Deal er s ( Season Naked And Afraid (Season 6): How I t ' s Made ( Season 16) : -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Eat. Drink. Talk. Zur Funktion von fictional bars in US-amerikanischen Fernsehserien.“ Verfasserin Sabine Baumgartner angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater-, Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ulrich Meurer, M.A. Sabine Baumgartner – 2 – Sabine Baumgartner Ein großes DDaannkke,e …euch allen, die ihr stets für mich da wart und mich auf meinem Weg durch das Studium und vor allem durch den Prozess dieser Diplomarbeit begleitet haben! …vor allem Herrn Professor Meurer, für seine Unterstützung, Anregungen und die engagierte Betreuung. …meiner lieben Familie, die mich geistig, emotional – und zeitweise sogar räumlich - unterstützt hat, ohne euch wäre ich heute nicht hier! ….Maxi Ratzkowski für den geistigen Austausch und die zahlreichen Gespräche. …Steffi, dass du immer an mich geglaubt und mir die nötige Kraft gegeben hast! – 3 – Sabine Baumgartner – 4 – Sabine Baumgartner 1. Einleitung .............................................................................................................. 7 2. Räume .................................................................................................................. 8 3. Sozialer Raum ...................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Raumsoziologie (nach Löw)