Population Analysis of Endangered Northern Bottlenose Whales on the Scotian Shelf Seven Years After the Establishment of a Marine Protected Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subsurface and Nighttime Behaviour of Pantropical Spotted Dolphins in Hawai′I

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen 988 Subsurface and nighttime behaviour of pantropical spotted dolphins in Hawai′i Robin W. Baird, Allan D. Ligon, Sascha K. Hooker, and Antoinette M. Gorgone Abstract: Pantropical spotted dolphins (Stenella attenuata) are found in both pelagic waters and around oceanic is- lands. A variety of differences exist between populations in these types of areas, including average group sizes, extent of movements, and frequency of multi-species associations. Diving and nighttime behaviour of pantropical spotted dolphins were studied near the islands of Maui and Lana′i, Hawai′i, in 1999. Suction-cup-attached time–depth recorder/VHF-radio tags were deployed on six dolphins for a total of 29 h. Rates of movements of tagged dolphins were substantially lower than reported in pelagic waters. Average diving depths and durations were shallower and shorter than reported for other similar-sized odontocetes but were similar to those reported in a study of pantropical spotted dolphins in the pelagic waters of the eastern tropical Pacific. Dives (defined as >5 m deep) at night were deeper (mean = 57.0 m, SD = 23.5 m, n = 2 individuals, maximum depth 213 m) than during the day (mean = 12.8 m, SD = 2.1 m, n = 4 individuals, maximum depth 122 m), and swim velocity also increased after dark. These results, together with the series of deep dives recorded immediately after sunset, suggest that pantropical spotted dolphins around Hawai′i feed primarily at night on organisms associated with the deep-scattering layer as it rises up to the surface after dark. -

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce § 218.83

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce § 218.83 (b) The incidental take of marine (S) Risso’s dolphin (Grampus mammals under the activities identi- griseus)—1,306,404. fied in § 218.80(c) is limited to the fol- (T) Rough-toothed dolphin (Steno lowing species, by the identified meth- bredanensis)—5,911. od of take: (U) Sowerby’s beaked whale (1) Harassment (Level A and Level B) (Mesoplodon bidens)—63,156. for all Training and Testing Activities: (V) Sperm whale (Physeter (i) Mysticetes: macrocephalus)—82,282. (A) Blue whale (Balaenoptera (W) Spinner dolphin (Stenella musculus)—817. longirostris)—115,310. (B) Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera (X) Striped dolphin (Stenella edeni)—5,079. coerulealba)—1,222,149. (C) Fin whale (Balaenoptera (Y) True’s beaked whale (Mesoplodon physalus)—25,239. mirus)—99,123. (D) North Atlantic right whale (Z) White-beaked dolphin (Eubalaena glacialis)—955. (Lagenorhynchus albirostris)—16,400. (E) Humpback whale (Megaptera (iii) Pinnipeds: novaeangliae)—9,196. (A) Gray seal (Halichoerus grypus)— (F) Minke whale (Balaenoptera 14,511. acutorostrata)—336,623. (B) Harbor seal (Phoca vitulina)— (G) Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis)— 39,519. 54,766. (C) Harp seal (Pagophilus (ii) Odontocetes: groenlanica)—16,319. (A) Atlantic spotted dolphin (Stenella (D) Hooded seal (Cystophora frontalis)—994,221. cristata)—1,472. (B) Atlantic white-sided dolphin (E) Ringed seal (Pusa hispida)—1,795. (Lagenorhynchus acutus)—206,144. (F) Bearded seal (Erignathus (C) Blainville’s beaked whale barbatus)—161. (Mesoplodon densirostris)—164,454. (2) Mortality (or lesser Level A in- (D) Bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops jury) for all Training and Testing Ac- truncatus)—1,570,031. -

Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales

1994-1998 Action Plan for the Conservation of Cetaceans Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales Compiled by Randall R. Reeves and Stephen Leatherwood ,;•/• Zm^LJ,^^.,.^' nh' k.''-'._-tf;s»s=i^" lUCN lUCN/SSC Cetacean Specialist Group 1994 014 c. 2 lUCN The Worid Conservation Union 1994-1998 Action Plan for the Conservation of Cetaceans Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales Compiled by Randall R. Reeves and Stephen Leatherwood lUCN/SSC Cetacean Specialist Group lUCN >\ Tha Worid Consarvstion Union SPEC its SURVIVAL COMMISMOM i.f«i«u,<^c>™.. WWF Chic«oZoolo,itJS<Kiciy .>r< . FiMESMH^EDsnnB X,'^'„„»^ .o«iitv.i,oN lociiT, ENVIRONMENTAL TRUST Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales: 1994-1998 was made possible through the generous support of: Chicago Zoological Society DEJA, Inc. Greenpeace Environmental Trust Ocean Park Conservation Foundation People's Trust for Endangered Species Peter Scott lUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund (Sultanate of Oman) U.S. Marine Mammal Commission Whale & Dolphin Conservation Society World Wide Fund for Nature © 1994 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorized without permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is cited and the copyright holder receives a copy of the reproduced material. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. This document should be cited as: Reeves, R.R. and Leathenwood, S. 1994. Dolphins, Porpoises, and Whales: 1994-1998 Action Plan for the Conservation of Cetaceans. lUCN, Gland, Switzerland. 92 pp. ISBN 2-8317-0189-9 Published by lUCN, Gland, Switzerland. -

Draft PEIS Supplemental Seismic Take Tables

Acoustic Modeling and Marine Mammal Incidental Take Supplemental Tables 1 Atlantic OCS Proposed Geological and Geophysical Activities Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic Planning Areas DRAFT Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement VOLUME I Supplemental Seismic Take Tables U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Gulf of Mexico OCS Region Acoustic Modeling and Marine Mammal Incidental Take Supplemental Tables 3 SUPPLEMENT A SEISMIC TAKE TABLES Acoustic Modeling and Marine Mammal Incidental Take Supplemental Tables Supplemental Take MarineMammalIncidental and Modeling Acoustic Supplemental Table A-1 Seismic Annual Takes Seismic Level A Takes – Southall Criteria Year 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 ORDER CETACEA Suborder Mysticeti (Baleen Whales) Common Minke Whale 0.000 0.084 0.161 0.013 0.069 0.045 0.021 0.022 0.009 Sei Whale 0.002 0.211 0.405 0.035 0.178 0.115 0.057 0.060 0.030 Bryde's Whale 0.002 0.635 1.240 0.131 0.724 0.529 0.360 0.166 0.040 Blue Whale 0.000 0.831 1.623 0.164 0.915 0.664 0.439 0.208 0.043 Fin Whale 0.015 0.021 0.021 0.021 0.021 0.018 0.005 0.000 0.000 North Atlantic Right Whale 0.002 0.039 0.074 0.011 0.047 0.036 0.025 0.009 0.001 Humpback Whale 0.000 3.046 5.931 0.567 3.153 2.226 1.402 0.779 0.235 Suborder Odontoceti (Toothed Whales, Dolphins, and Porpoises) Short-beaked Common Dolphin 4.094 121.807 230.677 24.072 101.335 68.641 29.844 23.101 1.241 Pygmy Killer Whale 0.000 0.162 0.313 0.028 0.176 0.114 0.082 0.067 0.060 Short-Finned Pilot Whale 0.005 11.627 22.508 1.950 82.506 -

Genetic Drift Vs. Natural Selection in a Long-Term Small

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 4051–4065 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03319.x GeneticBlackwell Publishing Ltd drift vs. natural selection in a long-term small isolated population: major histocompatibility complex class II variation in the Gulf of California endemic porpoise (Phocoena sinus) ADRIAN MUNGUIA-VEGA,* YARELI ESQUER-GARRIGOS,* LORENZO ROJAS-BRACHO,‡ RICARDO VAZQUEZ-JUAREZ,* AINES CASTRO-PRIETO§ and SERGIO FLORES-RAMIREZ† *Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, SC Mar Bermejo 195, Playa Palo Santa Rita. La Paz, Baja California Sur, México 23090, †Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular y Genética de la Conservación, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California Sur, Km. 4.5 Carretera La Paz–Los Cabos, La Paz, Baja California Sur, México 23080, ‡Programa Nacional de Mamíferos Marinos, Instituto Nacional de Ecología/Centro de Investigación Científica y Educación Superior de Ensenada, Km. 107, Carretera Ensenada–Tijuana, Ensenada, Baja California, México 22860, §Centro de Investigación Científica y Educación Superior de Ensenada, Km. 107, Carretera Ensenada–Tijuana. Ensenada, Baja California, México 22860 Abstract Although many studies confirm long-term small isolated populations (e.g. island endemics) commonly sustain low neutral genetic variation as a result of genetic drift, it is less clear how selection on adaptive or detrimental genes interplay with random forces. We investi- gated sequence variation at two major histocompatibility complex (Mhc) class II loci on a porpoise endemic to the upper Gulf of California, México (Phocoena sinus, or vaquita). Its unique declining population is estimated around 500 individuals. Single-strand confor- mation polymorphism analysis revealed one putative functional allele fixed at the locus DQB (n = 25). At the DRB locus, we found two presumed functional alleles (n = 29), differ- ing by a single nonsynonymous nucleotide substitution that could increase the stability at the dimer interface of αβ-heterodimers on heterozygous individuals. -

Sea Watch Foundation – Northern Bottlenose Whale in UK Waters

SPECIES INFORMATION SHEET NORTHERN BOTTLENOSE WHALE IN UK WATERS DESCRIPTION The northern bottlenose whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus, is probably the best- studied species within the beaked whale family, Ziphiidae. Males are from 8.5-9.8 metres and females 7.5-8.7 metres in length. The most distinctive feature of the species is the bulbous forehead (particularly pronounced in adult males) and its relatively short, dolphin-like beak. There are two teeth at the tip of the lower jaw, which only erupt in adult males. The dorsal fin is relatively tall and sickle-shaped, and situated nearly two-thirds of the way along the back. As in other beaked whales, the tail flukes lack a central notch. The body colour is chocolate brown, to yellowish (depending on whether there is a growth of diatoms over the skin), and adult males have a white patch on the forehead. At sea, the blow is bushy, about 2 metres high, and slightly forward-pointing. DISTRIBUTION AND STATUS The range of the northern bottlenose whale is restricted to the North Atlantic, where it occurs mainly in cold temperate and sub-arctic waters. The species favours deep ocean trenches, such as occur off Newfoundland (particularly “the Gully”), western Norway, and in the Barents Sea. Its migration pattern is more complex than a mere north-south movement, and some populations seem to be resident year-round. The distribution seems to be strongly influenced by that of its major prey - squid of the genus Gonatus. Northern bottlenose whales are found mainly in deep waters of greater than 1,000 m depth, often over submarine canyons and adjacent to the continental shelf edge, although they sometimes enter more shallow waters (300 m or less depth), and in January 2006, one even found its way up the river Thames to the city of London! In waters adjacent to the UK and Ireland, the species is sighted primarily in the Faroe-Shetland Channel, Rockall Trough, and southern Bay of Biscay, but it has been seen on occasions in coastal waters, for example around the Isle of Skye or off Northern Scotland. -

Sperm Whale Physeter Macrocephalus

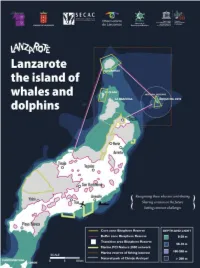

Secac Sightings! 3.900 There’s evidence of 30 species of cetaceans belon - sightings ging to 7 families in the Canary Archipel, which is a 34.5 % of the 87 species described in the whole pla - net; this makes The Canary Islands one of the areas with more diversity of cetaceans in the Atlantic North, specially with rare oceanic species and little known globally. Journeys Under effort Out of effort are one of The Canary Islands diversity the areas with more tlantic of cetaceans in the A North. teventura Lanzarote and Fuer t of high are a reference poin ns: 28 diversity of cetacea he Canary species of the 30 in t here. Islands are present Secac Secac 4.700 horas 58.820 miles hours Watching Sailing (108.010 km) Marine Mammals Did you Marine Mammals There’s evidence of 87 cetaceans species in the planet. As all the mammals, they’re warm-blooded animals, know they do breath atmospheric air, they give birth and feed the young with the milk from their mammary glands. that… There’s a huge variety of shapes and sizes, from 1,5m exceeding rarely the 50 kg (as for example the Vaquita) , to 28 m and more with 100.000kg (as the Blue rorqual). More than 70 million years of evolution 65 million years Mesonchids Pakicetus Ambulocetus The incursion into the water was gradual and took As a result of a progressive adaptation to this environment, cetaceans show place probably in the rivers , lakes and estuaries. an extreme anatomic and physiologic specialization, considering that they’ve lost the majority of the morphological characteristics which identify the rest of the mammals. -

Northern Bottlenose Whale (Scotian Shelf Population)

SPECIES AT RISK ACT Legal listing consultation workbook Northern Bottlenose Whale – Scotian Shelf Population (Hyperoodon ampullatus) Aussi disponible en français 1 Addition of species to the Species at Risk Act Introductory Information the Act is Schedule 1, the list of the The Species at Risk Act species that receive protection under The Species at Risk Act (SARA) SARA, commonly referred to as the strengthens and enhances the ‘SARA list’. Government of Canada’s capacity to protect Canadian wildlife species, The existing SARA list reflects the subspecies and distinct populations that 233 species the Committee on the Status are at risk of becoming Extinct or of Endangered Wildlife in Canada Extirpated. The Act applies only to (COSEWIC) had assessed and found to species on the SARA list. be at risk at the time of the reintroduction of SARA to the House of th Openness and transparency, including Commons on October 9 , 2002. public consultation, is required in making decisions about which species For more information on Species at Risk should be included on the SARA list. visit www.sararegistry.gc.ca The process begins with the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Role of COSEWIC Canada (COSEWIC) assessing a species COSEWIC comprises experts on as being at risk. Upon receipt of these wildlife species at risk. Their assessments, the Minister of the backgrounds are in the fields of biology, Environment, in consultation with the ecology, genetics, aboriginal traditional Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, has knowledge and other relevant fields, and 90 days to report on how he or she they come from various communities, intends to respond to the assessment and including government, academia, to the extent possible, provide timelines Aboriginal organizations and non- for action. -

Aloha & Welcome!

82nd HIHWNMS Sanctuary Advisory Council Meeting Tuesday, September 15, 2020 9:00 am – 11:30 am Public Comment: 10:50 am Aloha & Welcome! • You will begin in muted mode, but the session organizer can un-mute your connection at appropriate times & the “Chat” box will be open for submitting messages. • Primary Council Members: When you initially join, you will not at first have the ability to show yourself via your camera, nor be heard via audio. Staff will switch your status to “Panelist” & then you will have full control of your camera & audio. Due to camera limits only folks speaking should share their camera. • All Other Attendees: You will enter in muted mode & you will not be able to utilize your webcam. To get the attention of the organizer, please enter a note in the chat box. • All Participants: If you have trouble accessing the webinar, or problems occur during the session & you can’t enter it into the chat box, you can email [email protected] or check out https://support.goto.com/webinar 9:00 AM – 9:20 AM WELCOME/COUNCIL BUSINESS (SOL) • Roll Call (Kawika) • Review and approval of July 29, 2020 Meeting Minutes (Maka‘ala Ka‘aumoana) APPROVE JULY 29, 2020 MEETING MINUTES SHOWING PAGE 1 FOR VISUAL REFERENCE. DRAFT MEETING MINUTES CAN BE FOUND IN YOUR HANDOUTS SECTION OF CONTROL PANEL. 9:00 AM – 9:20 AM • Additional announcements from executive officers if any • Brief review and summary of previous issues, action items, and status (Cindy) • Completed: • Creation of a Native Hawaiian Culture subcommittee • Resolution supporting the -

C:\Carretta\DOCS\HI Abundance V2.Wpd

CETACEAN ABUNDANCE IN HAWAIIAN WATERS DURING SUMMER/FALL OF 2002 Jay Barlow Southwest Fisheries Science Center 8604 La Jolla Shores Dr. La Jolla, CA 92037 ABSTRACT The abundance of cetaceans is estimated for the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) around the Hawaiian Islands based on a survey in August-November 2002. Two NOAA research vessels were used for this line-transect survey. Sighting detection functions were estimated from this and other NOAA research surveys from 1986 to 2002 using a new, multiple-covariate approach. Twenty four species were seen on this survey, including two species (Fraser’s dolphin - Lagenodelphis hosei and sei whale - Balaenoptera borealis) that had not been previously documented to occur in Hawaiian waters. The most abundant large whales were sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) and Bryde’s whales (Balaenoptera edeni). The most abundant delphinids were rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis) and Fraser’s dolphins (Lagenodelphis hosei). Dwarf and pygmy sperm whales (Kogia simus and K. breviceps) and Cuvier’s beaked whales (Ziphius cavirostris) were estimated to be quite abundant. Some of the migratory baleen whales (fin whales - Balaenoptera physalus, sei whales, minke whales - B. acutorostrata, and humpback whales - Megaptera novaeangliae) were seen only late in the survey. Abundance could be estimated for 21 cetacean species, but the estimated abundances of migrating whales do not correspond to their period of highest abundance in this area. The overall density of cetaceans was low in the study area, especially for delphinids. The precision of density and abundance estimates was generally low for all species due to the small number of sightings. -

![The Rorqual] Is of Great Size and Length… Because of Its Quiet and Peaceful Behavior It Often Falls a Prey to Whale Fishers](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0514/the-rorqual-is-of-great-size-and-length-because-of-its-quiet-and-peaceful-behavior-it-often-falls-a-prey-to-whale-fishers-3860514.webp)

The Rorqual] Is of Great Size and Length… Because of Its Quiet and Peaceful Behavior It Often Falls a Prey to Whale Fishers

Olaus Magnus Carta Marina 1539 Jónsbók AM 350 fol. / Arni Magnusson Institute Jónsbók GKS 3269 a 4to / Arni Magnusson Institute “They put to sea and arrived safe and sound at Leif’s Houses and carried their hammocks ashore. Soon they had plenty of good supplies, for a fine big rorqual was driven ashore; they went down and cut it up, and so there was no shortage of food.” Grænlendinga saga. “The next thing to be told is that a whale was stranded in Isafjord. Thorbjorn and Havard had drift rights on both sides. The first report was that the whale belonged to Havard. It was a splendid finback whale. Both went there and decided to accept the lawspeaker’s verdict.” Hávarðar saga Ísfirðings Rorquals or Balaenopteridae Blue, Fin, Sei, Humpback, Minke Olaus Magnus, Historia, 1555 Olaus Magnus, Historia, 1555 ‘Red comb’ Narwhal Sperm whale Gray whale Right whale Humpback whale Blue whale “... This fish is the best of all for food. It is of a peaceful disposition and does not bother ships, though it may swim very close to them. [The rorqual] is of great size and length… Because of its quiet and peaceful behavior it often falls a prey to whale fishers. It is better for eating and smells better than any of the other fishes that we have talked about, though it is said to be very fat; it has no teeth. It has been asserted, too, that the sperm of this whale... will be found to be a most effective remedy for eye troubles, leprosy, ague, headache, and for every other ill that afflicts mankind.” – The King’s Mirror Various Orkney & LAM L’Anse aux Meadows Bretta Ness, Rousay, Orkney Sei whale (?) Sperm whale Bowhead whale Fin whale National Museums Scotland Collections Centre, Granton Red Bay, Labrador Blue whale Fin whale Humpback whale Sei whale Minke whale Sperm whale N. -

A Note on Concentrations of Metals in Cetaceans from Southern Africa

J. CETACEAN RES. MANAGE. (SPECIAL ISSUE I), 177-194, 1999 A note on concentrations of metals in cetaceans from southern Africa JOHN HENRY 54A Creffield Road, Colchester, CO3 3HY, England AND PETER BEST* Mammal Research Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, 0002 South Africa Contact e-mail: [email protected].:a ABSTRACT Concentrations of zinc, copper, cadmium, mercury and lead were measured by atomic absorption spectrophotometry in samples of the brain, kidney , liver and muscle tissue from 178 individuals of 323 different cetacean species (4 right whales - Eubalaena australis, 2 pygmy right whales - Caperea marginara, 3 minke whales - Balaenoptera acutorostrata, 3 Bryde's whales - B. edeni, 1 humpback whale - Megaptera novaeangliae, 1 sperm whale - Physeter macrocephalus, 11 pygmy sperm whale - Kogia breviceps, 6 dwarf sperm whales - K. simus, 1 southern bottlenose whale - Hyperoodon planifrons, 1 Cuvier's beaked whale - Ziphius cavirostris, 9 Blainville's beaked whales - Mesoplodon densirostris, 5 strap-tooth whales - M. layardii, 2 True's beaked whales - M. mirus, 3 long-finned pilot whales - Globicephala me/as, 30 Risso's dolphins - Grampus griseus, 12 bottlenose dolphins - Tursiops truncatus, 5 striped dolphins - Stenella coeruleoalba, 1 pantropical spotted dolphin - S. attenuata, 1 hump-backed dolphin - Sousa chinensis, 21 dusky dolphins - Lagenorhynchus obscurus, 1 hourglass dolphin - L. cruciger, 12 Heaviside's dolphins - Cephalorhynchus heavisidii and 43 common dolphins - Delphinus delphis). All but the hourglass dolphin were strandings or animals taken incidental to fishing operations or under scientific permit in coastal waters of South Africa or Namibia. Highest concentrations of Zn, Cu and Hg were generally found in the liver and of Cd in the kidney.