The Life of Elizabeth Barrett Browning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q0q765 Author Browning, Catherine Cronquist Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature By Catherine Cronquist Browning A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor Paula Fass Fall 2013 Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature © 2013 by Catherine Cronquist Browning Abstract Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature by Catherine Cronquist Browning Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Ian Duncan, Chair Bower of Books: Reading Children in Nineteenth-Century British Literature analyzes the history of the child as a textual subject, particularly in the British Victorian period. Nineteenth-century literature develops an association between the reader and the child, linking the humanistic self- fashioning catalyzed by textual study to the educational development of children. I explore the function of the reading and readable child subject in four key Victorian genres, the educational treatise, the Bildungsroman, the child fantasy novel, and the autobiography. I argue that the literate children of nineteenth century prose narrative assert control over their self-definition by creatively misreading and assertively rewriting the narratives generated by adults. The early induction of Victorian children into the symbolic register of language provides an opportunity for them to constitute themselves, not as ingenuous neophytes, but as the inheritors of literary history and tradition. -

The Afterlives of Elizabeth Barrett Browning

This is a postprint! The Version of Record of this manuscript has been published and is available in a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 31:1 (2016), 83-107, http://www.tandfonline.com, DOI: 10.1080/08989575.2016.1092789. The Notable Woman in Fiction: The Afterlives of Elizabeth Barrett Browning Julia Novak Abstract: Drawing on gender-sensitive approaches to biographical fiction, this paper examines fictional representations of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, from Carola Oman’s Miss Barrett’s Elopement to Laura Fish’s Strange Music. With a focus on their depiction of her profession, the novels are read as part of the poet’s afterlife and reception history. This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) under Grant T 589-G23. “Let it be fact, one feels, or let it be fiction; the imagination will not serve under two masters simultaneously,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her review essay “The New Biography.”1 While her observation was addressed to the biographer, Woolf herself demonstrated that for the novelist it was quite permissible, as well as profitable, to mingle fact and fiction in the same work. Her biographical novella of Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s cocker spaniel, Flush: A Biography, provides an imaginative account of not only the dog’s experiences and perceptions but also, indirectly, those of its famous poet-owner, whom critic Marjorie Stone introduces as “England’s first unequivocally major female poet” (3). Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s professional achievements as well as her personal history secured her public status as a literary celebrity, which lasted, in varying forms, well beyond the nineteenth century and inspired several other biographical fictions before and after Woolf’s canine biography. -

The Absentee

The Absentee Maria Edgeworth The Absentee Table of Contents The Absentee..............................................................................................................................................................1 Maria Edgeworth............................................................................................................................................1 i The Absentee Maria Edgeworth NOTES ON 'THE ABSENTEE' In August 1811, we are told, she wrote a little play about landlords and tenants for the children of her sister, Mrs. Beddoes. Mr. Edgeworth tried to get the play produced on the London boards. Writing to her aunt, Mrs. Ruxton, Maria says, 'Sheridan has answered as I foresaw he must, that in the present state of this country the Lord Chamberlain would not license THE ABSENTEE; besides there would be a difficulty in finding actors for so many Irish characters.' The little drama was then turned into a story, by Mr. Edgeworth's advice. Patronage was laid aside for the moment, and THE ABSENTEE appeared in its place in the second part of TALES OF FASHIONABLE LIFE. We all know Lord Macaulay's verdict upon this favourite story of his, the last scene of which he specially admired and compared to the ODYSSEY. [Lord Macaulay was not the only notable admirer of THE ABSENTEE. The present writer remembers hearing Professor Ruskin on one occasion break out in praise and admiration of the book. 'You can learn more by reading it of Irish politics,' he said, 'than from a thousand columns out of blue−books.'] Mrs. Edgeworth tells us that much of it was written while Maria was suffering a misery of toothache. Miss Edgeworth's own letters all about this time are much more concerned with sociabilities than with literature. We read of a pleasant dance at Mrs. -

1931 Article Titles and Notes Vol. III, No. 1, January 10, 19311

1931 article titles and notes Vol. III, No. 1, January 10, 19311 "'The Youngest' Proves Entertaining Production of Players' Club. Robert W. Graham Featured in Laugh Provoking Comedy; Unemployed to Benefit" (1 & 8 - AC, CO, CW, GD, and LA) - "Long ago it was decided that the chief aim of the Players' Club should be to entertain its members rather than to educate them or enlighten them on social questions or use them as an element in developing new ideas and methods in the Little Theatre movement."2 Philip Barry's "The Youngest" fit the bill very well. "Antiques, Subject of Woman's Club. Chippendale Furniture Discussed by Instructor at School of Industrial Art. Art Comm. Program" (1 - AE and WO) - Edward Warwick, an instructor at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art, spoke to the Woman's Club on "The Chippendale Style in America." "Legion Charity Ball Jan. 14. Tickets Almost Sold Out for Benefit Next Friday Evening. Auxiliary Assisting" (1 & 4 - CW, LA, MO, SN, VM, and WO) - "What was begun as a Benefit Dance for the Unemployed has grown into a Charity Ball sponsored by the local America Legion Post with every indication of becoming Swarthmore's foremost social event of the year." The article listed the "patrons and patronesses" of the dance. Illustration by Frank N. Smith: "Proposed Plans for New School Gymnasium" with caption "Drawings of schematic plans for development of gymnasium and College avenue school buildings" (1 & 4 - BB, CE, and SC) - showed "how the 1.035 acres of ground just west of the College avenue school which was purchased from Swarthmore College last spring might be utilized for the enlargement of the present building into a single school plant." "Fortnightly to Meet on Monday" (1 - AE and WO) - At Mrs. -

"Problem" MWF 2 Cross Listed with AADS4410 Satisfies Cultural Diversity Core Requirement in the Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B

SPOTLIGHT ON ENGLISH ELECTIVES SPRING 2018 ENGL2482 African American Literature and the "Problem" MWF 2 Cross listed with AADS4410 Satisfies Cultural Diversity Core Requirement In The Souls of Black Folk, W.E.B. Du Bois famously observes that to be black is to serially confront a question: "How does it feel to be a problem?" This course undertakes a survey of African American Literature as an ongoing mediation on the "problem" of being black, from the advent of racial slavery through to its contemporary afterlives. Reading broadly across a black literary tradition spanning four centuries and multiple genres, we will consider how black writers represent the "problem" of being black not merely as an unwelcome condition to be overcome, but an ethical orientation to be embraced over against an anti-black world that is itself a problem. Jonathan Howard ENGL3331 Victorian Inequality MWF 11 Fulfills the pre-1900 requirement. From “Dickensian” workhouses to shady financiers, Victorian literature has provided touchstones for discussions of inequality today. This course will investigate how writers responded to the experience of inequality in Victorian Britain during an era of revolution and reaction, industrialization and urbanization, and empire building. Considering multiple axes of inequality, we will explore topics such as poverty and class conflict, social mobility, urbanization, gender, education, Empire, and labor. We will read novels, poetry, and nonfiction prose; authors include Alfred, Lord Tennyson; Elizabeth Gaskell; Charles Dickens; Elizabeth Barrett Browning; Mary Prince; Arthur Morrison; and Thomas Hardy. Aeron Hunt ENGL4003 Shakespeare and Performance T TH 12 Fulfills pre-1700 requirement Although Shakespeare became “literature,” people originally encountered Shakespeare’s plays as popular entertainment. -

19Th Century

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Poetry [minimum 10 poets] 1. William Blake a. “The Ecchoing Green” [Songs of Innocence] (1789) b. “The Divine Image” [Songs of Innocence] (1789) c. “Holy Thursday” [Songs of Innocence] (1789) d. “Holy Thursday” [Songs of Experience] (1794) e. “The Human Abstract” [Songs of Experience] (1794) f. “London” [Songs of Experience] (1794) 2. William Wordsworth a. “Simon Lee” (1798) b. The Prelude, Books I-III, VII, IX-XIII (1805) c. “Ode: Intimations of Immortality” (1807) 3. Percy Bysshe Shelley a. “Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude” (1815) b. “Mont Blanc” (1817) c. “To a Skylark” (1820) 4. George Gordon, Lord Byron a. “Darkness” (1816) b. Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto III-IV (1816; 1818) 5. John Keats a. “Ode to a Nightingale” (1819) b. “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (1819) c. “Ode on Melancholy” (1819) d. “To Autumn” (1819) 6. Alfred, Lord Tennyson a. “The Lotos-Eaters” (1832; rev. 1842) b. In Memoriam (1850) c. “Tithonus” (1860) 7. Elizabeth Barrett Browning a. “The Cry of the Children” (1843) b. “The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point” (1850) c. Aurora Leigh (1856) 8. George Meredith a. Modern Love (1862) 9. Christina Rossetti a. “Goblin Market” (1862) b. “The Convent Threshold” (1862) c. “Memory” (1866) d. “The Thread of Life” (1881) 10. Robert Browning a. “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” (1855) b. The Ring and the Book (1868-9) 11. Augusta Webster a. “Circe” (1870) b. “The Happiest Girl in the World” (1870) c. “A Castaway” (1870) Fiction [minimum 10 novelists] 1. Ann Radcliffe, The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) 2. -

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Poems Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ROBERT AND ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING POEMS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Browning,Elizabeth Barrett Browning,Peter Washington | 256 pages | 28 Feb 2003 | Everyman | 9781841597522 | English | London, United Kingdom Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning Poems PDF Book Alexander Neubauer. A blue plaque at the entrance to the site attests to this. Retrieved 23 October Virginia Woolf called it "a masterpiece in embryo". Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in Florence on June 29, Her mother's collection of her poems forms one of the largest extant collections of juvenilia by any English writer. Retrieved 22 September Here's another love poem from the Portuguese cycle , too, Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. Olena Kalytiak Davis Fredeman and Ira Bruce Nadel. Carl Sandburg Here's a very brief primer on a bold and brilliant talent. In the newly elected Pope Pius IX had granted amnesty to prisoners who had fought for Italian liberty, initiated a program looking forward to a more democratic form of government for the Papal State, and carried out a number of other reforms so that it looked as though he were heading toward the leadership of a league for a free Italy. During this period she read an astonishing amount of classical Greek literature—Homer, Pindar, the tragedians, Aristophanes, and passages from Plato, Aristotle, Isocrates, and Xenophon—as well as the Greek Christian Fathers Boyd had translated. Her prolific output made her a rival to Tennyson as a candidate for poet laureate on the death of Wordsworth. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Vice-Presidents: Robert Browning Esq. Burton Raffel. Sandra Donaldson et al. -

The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf for Students of Modern Literature, the Works of Virginia Woolf Are Essential Reading

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf For students of modern literature, the works of Virginia Woolf are essential reading. In her novels, short stories, essays, polemical pamphlets and in her private letters she explored, questioned and refashioned everything about modern life: cinema, sexuality, shopping, education, feminism, politics and war. Her elegant and startlingly original sentences became a model of modernist prose. This is a clear and informative introduction to Woolf’s life, works, and cultural and critical contexts, explaining the importance of the Bloomsbury group in the development of her work. It covers the major works in detail, including To the Lighthouse, Mrs Dalloway, The Waves and the key short stories. As well as providing students with the essential information needed to study Woolf, Jane Goldman suggests further reading to allow students to find their way through the most important critical works. All students of Woolf will find this a useful and illuminating overview of the field. JANE GOLDMAN is Senior Lecturer in English and American Literature at the University of Dundee. Cambridge Introductions to Literature This series is designed to introduce students to key topics and authors. Accessible and lively, these introductions will also appeal to readers who want to broaden their understanding of the books and authors they enjoy. Ideal for students, teachers, and lecturers Concise, yet packed with essential information Key suggestions for further reading Titles in this series: Bulson The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce Cooper The Cambridge Introduction to T. S. Eliot Dillon The Cambridge Introduction to Early English Theatre Goldman The Cambridge Introduction to Virginia Woolf Holdeman The Cambridge Introduction to W. -

PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY from the Victorians to the Present Day

PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY From the Victorians to the present day Information and Activities for Secondary Teachers of Art and Photography John French Lord Snowdon, vintage bromide print, 1957 NPG P809 © SNOWDON / Camera Press Information and Activities for Secondary Teachers of Art and Photography Contents Introduction 3 Discussion questions 4 Wide Angle 1. Technical beginnings and early photography Technical beginnings 5 Early photography 8 Portraits on light sensitive paper 11 The Carte-de-visite and the Album 17 2. Art and photography; the wider context Art and portrait photography 20 Photographic connections 27 Technical developments and publishing 32 Zoom 1. The photographic studio 36 2. Contemporary photographic techniques 53 3. Self image: Six pairs of photographic self-portraits 63 Augustus Edwin John; Constantin Brancusi; Frank Owen Dobson Unknown photographer, bromide press print, 1940s NPG x20684 Teachers’ Resource Portrait Photography National Portrait Gallery 3 /69 Information and Activities for Secondary Teachers of Art and Photography Introduction This resource is for teachers of art and photography A and AS level, and it focuses principally on a selection of the photographic portraits from the Collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London which contains over a quarter of a million images. This resource aims to investigate the wealth of photographic portraiture and to examine closely the effect of painted portraits on the technique of photography invented in the nineteenth century. This resource was developed by the Art Resource Developer in the Learning Department in the Gallery, working closely with staff who work with the Photographs Collection to produce a detailed and practical guide for working with these portraits. -

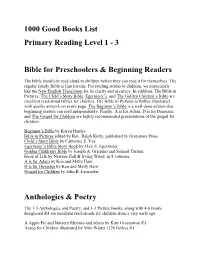

1000 Good Books List Primary Reading Level 1 - 3

1000 Good Books List Primary Reading Level 1 - 3 Bible for Preschoolers & Beginning Readers The Bible should be read aloud to children before they can read it for themselves. The regular family Bible is fine for this. For reading stories to children, we particularly like the New English Translation for its clarity and accuracy. In addition, The Bible in Pictures, The Child’s Story Bible, Egermeier’s, and The Golden Children’s Bible are excellent read-aloud Bibles for children. The Bible in Pictures is further illustrated with quality artwork on every page. The Beginner’s Bible is a well-done edition that beginning readers can read independently. Finally, A is for Adam, D is for Dinosaur, and The Gospel for Children are highly recommended presentations of the gospel for children. Beginner’s Bible by Karyn Henley Bible in Pictures edited by Rev. Ralph Kirby, published by Greystone Press Child’s Story Bible by Catherine E. Vos Egermeier’s Bible Story Book by Elsie E. Egermeier Golden Children's Bible by Joseph A. Grispino and Samuel Terrien Book of Life by Newton Hall & Irving Wood, in 8 volumes A is for Adam by Ken and Mally Ham D is for Dinosaur by Ken and Mally Ham Gospel for Children by John B. Leuzarder Anthologies & Poetry The 1-3 Anthologies and Poetry, and 1-3 Picture Books, along with 4-6 books designated RA are excellent read-alouds for children from a very early age. A Apple Pie and Nursery Rhymes and others by Kate Greenaway RA Aesop for Children illustrated by Milo Winter (126 fables) RA Alan Garner’s Fairy Tales of Gold by Alan -

First Grade Supplemental Reading List

First Grade Supplemental Reading List Anthologies: • A Kate Greenaway Family Treasury by Kate Greenaway • Aesop’s Fables illustrated by Thomas Bewick • Alan Garner’s Fairy Tales of Gold by Alan Garner • Best-Loved Fairy Tales by Walter Crane • Caldecott’s Favorite Nursery Rhymes by Randolph Caldecott • Child’s Garden of Verses by Robert Louis Stevenson, illustrated by Jessie Willcox Smith • Child’s Treasury of Poems by Mark Daniel • Children’s Treasury of Virtues by William Bennett, illustrated by Michael Hague, and others in the series • Fables by Arnold Lobel • Fairy Tales by Hans Christiansen, illustrated by Peedersen and Frolich • Favorite Poems of Childhood by Philip Smith • Great Children’s Stories: The Classic Volland Edition, illus. by F. Richardson • Happy Prince and Other Fairy Tales by Oscar Wilde • How Many Spots Does a Leopard Have? and Other Tales, retold by Julius Lester • In a Circle Long Ago: A Treasury of Native Lore from North America, retold by Nancy Van Laan • James Herriot’s Treasury for Children by James Herriot • Johnny Appleseed, poem by Reeve Lindbergh, illustrated by Kathy Jakobsen • Let’s Play: Traditional Games of Childhood, Camilla Gryski • Moral Tales by Maria Edgeworth • Mother Goose’s Melodies (Facsimile of the Munroe and Francis “Copyright 1833” Version) • My Favorite Story Book by W. G. Vande Hulst RA • Nonsense Poems and others by Edward Lear RA • Now We Are Six by A. A. Milne RA • Nursery and Mother Goose Rhymes by Marguerite de Angeli • Once On A Time by A. A. Milne RA • Over the River and Through the Wood, by Lydia Maria Child, illustrated by Brinton Turkle • Paddington Treasury, by Michael Bond • Parent’s Assistant by Maria Edgeworth RA • Pleasant Field Mouse Storybook by Jan Wahl • Poems to Read to the Very Young by Josette Frank • Prince Rabbit by A. -

Vol. 3 No.3, September, 2018

Vol. 3 No.3, September, 2018 Editor: Dr. Saikat Banerjee Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences St. Theresa International College, Thailand. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 A UGC Refereed e- Journal no 45349 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.3, No.3, September, 2018 Romancing with the Pet: Animal Identity and Alterity in Virginia Woolf’s Flush Amrita Goswami Research Scholar Department of English The University of Burdwan Burdwan, West Bengal, India Received 10 August 2018 Revised 27 August 2018 Accepted 4 September 2018 Abstract: Virginia Woolf’s Flush: A Biography (1933), a reconstruction of the life of Elizabeth Barrett’s pet spaniel, is a radical experiment with the genre of biography. By taking a dog as biographical subject Woolf attempts to deconstruct the traditional anthropocentric notion of biography. While traditional literature has de-valued animal studies, Woolf’s text tries to construct a distinct animal identity within a Victorian family. The presence of the pet within the family has been treated as an alterity which threatens the bourgeois domestic value of ‘reproductive futurism’. She has also shown how man and animal share spaces with multifaceted ramification and the possibility of an affective relation with the pet beyond the traditional parameters of sexuality. The intimate relation between Elizabeth and Flush can be read as a parallel narrative of romance co- existing with the love affair between Elizabeth and Robert Browning. Key Words: Pet-narrative, Romance, Biography, Alterity, Reproductive futurism. “Hers was the pale worn face of an invalid, cut off from air, light, freedom. His was the warm ruddy face of a young animal; instinct with health and energy.