Health and Autonomy: the Case of Chiapas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TUXTLA GUTIÉRREZ L Platanal Ío

L E L E L EL E EL L E L E E L EL E E L L E E L E L E L L L E L L E E L E E L L E 1 E 0 0 0 L E L EL L E L E E L E E L E L L L E L E E E L L 1 L 5 E 0 0 E EL L E L L L L E E E E E E L L L L L E E !( !( E L L E !( L E L E E L E L L L E E L L E E E EL L !( EL !( L E E L E L L E L E L !( L E EL E E !( L L E E E L E E L L L L E L L E !( L E )" E E E !( L L E L E L !( L E E E L L !( E L E E L L !( EL E # L L L E !( E E C.H. E L L L L E E E E L L E L L L E !( # L !( L E Bombaná !( E E E E L !( L ©! !( E !( !( L L !( E E !( L L !( L E L E # L E !( L E E E L !( E L E L E !( !(!( L E L EL L E EL !( E !( EL L L L E E E L E E E L L L L E E !( L E L L E L E E L !( # # L E E L L L L E !( L E E !( E L E L L E L !( EL E L E E L E E E EL L L !( E L L E L E O E L E E Ï L E EL L L E L E L E L L La EL o S E L !( E y o ' E !( E L ro m !( L L L E EL EL Ar b E L L r E a E ©! E E L L L 1 !( EL L L 5 E E EL C.H. -

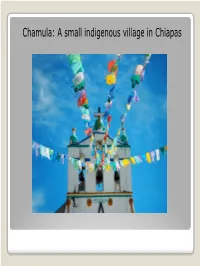

Chamula: a Small Indigenous Village in Chiapas

Chamula: A small indigenous village in Chiapas StateState ofof Chiapas,Chiapas, MexicoMexico ChamulaChamula This is a community of Pre-Hispanic origin whose name means "Thick "Water." The Chamulas have always been fiercely independent: they resisted the Spanish upon their arrival in 1524 and later staged a famous rebellion in 1869, attacking the nearby colonial settlement of San Cristobal. San Juan Chamula is the principal town, being the main religious and economic center of the community. The Chamulas enjoy being a closed community. Like other indigenous communities in this region, they can be identified by their clothes: in this case distinctive purple and pink colors predominate. This Tzotzil community is considered one of most important of its kind, not only by sheer numbers of population, but by customs practices here, as well. Information taken from www.luxuriousmexico.com This is the house of someone who migrated to the States to work and returned to build a house styled like those he saw in the United States. In the distance is the town square with This picture was taken in front the cathedral. of the cathedral. Sheep are considered sacred by the Chamula. Thus, they are not killed but allowed to graze and used for their wool. How do you think this happened historically? TheThe SundaySunday MarketMarket GirlGirl withwith HuipilHuipil SyncretismSyncretism Religious syncretism is the blending of two belief systems Religious syncretism often takes place when foreign beliefs are introduced to an indigenous belief system and the teachings are blended For the indigenous peoples of Mexico, Catholic beliefs blended with their native The above picture shows the religious beliefs traditional offerings from a Mayan Syncretism allowed the festival with a picture of Jesus, a native peoples to continue central figure in the Christian religion. -

Región Iii – Mezcalapa

REGIÓN III – MEZCALAPA Territorio La región socioeconómica III Mezcalapa, según el Marco Geoestadístico 2010 que publica el INEGI, tiene una superficie de 2,654.95 km2 y se integra por 9 municipios localizados en la parte noroeste del estado. Colinda al norte con el estado de Tabasco y con la Región VIII Norte, al este con la Región VII De los bosques, al sur con la Región II Valles Zoque y al oeste con el estado de Oaxaca La cabecera regional es la ciudad es Copainalá. SUPERFICIE SUPERFICIE CABECERAS MUNICIPALES MUNICIPIO (% (km2) REGIONAL) NOMBRE ALTITUD Chicoasén 115.24 4.34 Chicoasén 251 Coapilla 154.89 5.83 Coapilla 1,617 Copainalá 346.14 13.04 Copainalá 450 Francisco León 209.93 7.91 Rivera el Viejo Carmen 827 Mezcalapa 847.31 31.91 Raudales Malpaso 136 Ocotepec 61.09 2.30 Ocotepec 1,436 Osumacinta 92.22 3.47 Osumacinta 388 San Fernando 359.26 13.53 San Fernando 912 Tecpatán 468.87 17.66 Tecpatán 318 TOTAL 2,654.95 Nota: la altitud de las cabeceras municipales está expresada en metros sobre el nivel del mar. Se ubica dentro de las provincias fisiográficas que se reconocen como Montañas del Norte y Altos de Chiapas. Dentro de las dos provincias fisiográficas de la región se reconocen cuatro formas del relieve sobre las cuales se apoya la descripción del medio físico y cultural del territorio regional. En la zona norte, este y oeste de la región predomina la sierra alta escarpada y compleja y la sierra alta de laderas tendidas; al sur de la región predomina la sierra alta de laderas tendidas, seguido de sierra alta escarpada y compleja y en menor proporción el cañón típico. -

Agroindustrias De Mapastepec Sa De Cv According to the Requirements of the Rspo Principles & Criteria

Doc. 2_3_3_En ANNOUNCEMENT OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION REGARDING THE INITIAL CERTIFICATION AUDIT OF - AGROINDUSTRIAS DE MAPASTEPEC SA DE CV ACCORDING TO THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE RSPO PRINCIPLES & CRITERIA Dear Sir or Madam, IBD Certificações informs that the company Agroindustrias de Mapastepec SA de CV (RSPO member n° 2- 0360-12-000-00) is now in the application process for RSPO Principles & Criteria Certification related to the production of sustainable palm oil production. The audit is scheduled to take place between March 08 of 2021 and March 12 of 2021. Agroindustrias de Mapastepec SA de CV Address Av. Lopez Mateos Norte. No. Ext. 391, No. Int Piso 21-A, Torre Bansi, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Contact person Jorge Coronel Phone / email +523336487800 / [email protected] Scope Production and sales of Palm Oil and Palm Kernel Products Palm Oil and Palm Kernel Standards that will be used for this assessment Mexican National Interpretation Of The Rspo Principles And Criteria For The Production Of Sustainable Palm Oil 2018 Mill Estimated / Forecast GPS references Palm Oil Mill’s Name Address capacity annual production (Mt) Latitude Longitude (Ton/hr) CSPO CSPK Planta Extractora Calle Central S/N, 60 2000 400 15°20'42.3 92°51'53.9 Mapastepec Ejido Nicolás Bravo II, 4"N 4"O Mapastepec, Mexico Suppliers’ base GPS references Area summary (Ha) Annual estimated Name Address Planted area Latitude Longitude Total certified (mature + certified FFB area immature) production (Mt) Buenos Aires Mapastepec, Chiapas, 15°18'45.5 92°52'48.5 107,00 -

Mapastepec, Chiapas Informe Anual Sobre La Situación De Pobreza Y

InformeInforme Anual Anual Sobre Sobre La SituaciónLa Situación de Pobrezade Pobreza y Rezago y Rezago Social Social Mapastepec, Chiapas I. Indicadores sociodemográficos II. Medición multidimensional de la pobreza Mapastepec Chiapas Indicador Indicadores de pobreza y vulnerabilidad (porcentajes), (Municipio) (Estado) 2010 Población total, 2010 43,913 4,796,580 Total de hogares y viviendas 10,840 1,072,560 Vulnerable por particulares habitadas, 2010 carencias social Tamaño promedio de los hogares 1.4 44.4 (personas), 2010 2.3 Vulnerable por Hogares con jefatura femenina, 2010 2,672 216,407 46.4 ingreso Grado promedio de escolaridad de la 79.6 No pobre y no 66.7 16.6 población de 15 o más años, 2010 vulnerable Total de escuelas en educación básica y 33.2 19318,539 Pobreza moderada media superior, 2010 Personal médico (personas), 2010 61 5,373 Pobreza extrema Unidades médicas, 2010 61,314 Número promedio de carencias para la 3.13.2 población en situación de pobreza, 2010 Número promedio de carencias para la Indicadores de carencia social (porcentajes), 2010 población en situación de pobreza 3.93.9 88.3 extrema, 2010 82.4 Fuentes: Elaboración propia con información del INEGI y CONEVAL. 60.7 60.7 62.3 51.6 35 34.2 35.4 33.3 29.2 28.5 30.3 22.9 24.8 25.4 • La población total del municipio en 2010 fue de 43,913 20.7 15.2 personas, lo cual representó el 0.9% de la población en el estado. Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por Carencia por • En el mismo año había en el municipio 10,840 hogares (1% del rezago acceso a los acceso a la calidad y servicios acceso a la total de hogares en la entidad), de los cuales 2,672 estaban educativo servicios de seguridad espacios de básicos en la alimentación encabezados por jefas de familia (1.2% del total de la entidad). -

Artesanía, Una Producción Local Para Mercados Globales. El Caso De

Artesanía, una producción local para mercados globales. El caso de Amatenango del Titulo Valle, Chiapas México Tuñón Pablos, Esperanza - Autor/a; Carderon Cisneros, Araceli - Autor/a; Ramos Autor(es) Muñoz, Dora Elia - Autor/a; Bogotá Lugar Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Editorial/Editor 2000 Fecha Colección Artesanos; Artesanía; Desarrollo rural; Oficios; Mercados; Turismo; Los Altos de Temas Chiapas; México; Amatenango del Valle ; Ponencias Tipo de documento http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/Colombia/fear-puj/20130218025451/ramos.pdf URL Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.0 Genérica Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar Ramos Muñoz, Dora Elia; Muñón Pablos, Esperanza; Carderon Cisneros, Araceli. Artesanía, una producción local para mercados globales. El caso de Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas México. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Seminario Internacional, Bogotá, Colombia. Agosto de 2000 Disponible en la World Wide Web: http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/ar/libros/rjave/mesa2/ramos.pdf RED DE BIBLIOTECAS VIRTUALES DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES DE AMERICA LATINA Y EL CARIBE, DE LA RED DE CENTROS MIEMBROS DE CLACSO http://www.clacso.org.ar/biblioteca www.clacso.org [email protected] ARTESANÍA, UNA PRODUCCIÓN LOCAL PARA MERCADOS GLOBALES. EL CASO DE AMATENANGO DEL VALLE, CHIAPAS MÉXICO *1 Dora Elia Ramos Muñoz** Esperanza Tuñón Pablos*** Araceli Carderon Cisneros**** Teopisca, Chiapas a 15 de Junio de 2000 RESUMEN En este trabajo se examina el caso de la alfarería artesanal de Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas con el objetivo de plantear posibilidades para alentar la producción de artesanía, entendida como oficio comunitario y local, hacia mercados globales. -

Municipio De Amatenango Del Valle

92°30'0"W 92°27'30"W 92°25'0"W 92°22'30"W 92°20'0"W 92°17'30"W Municipio de HUIXTÁN Amatenango del Valle UBICACIÓN N " N " 0 ' 0 ' 5 5 3 ° 3 ° 6 6 1 1 CHANAL SAN CRISTÓBAL E DE LAS CASAS !( San Pedro Las Flores !( San Fernando las Flores !(Yalchitán Rosario Tzontehuitz !( San Vicente La Piedra San Isidro las Cuevas !( !( SIMBOLOGÍA La Merced !( Localidades según número de habitantes N " N !( " 0 )" 0 La Tejonera 3 No disponible De 500 a 999 !( ' 3 ' TEOPISCA 2 2 3 ° 3 !( ° 6 "/ 6 1 Menor a 100 De 1,000 a 2,499 1 !(La Granada San José La Ventana !( San Antonio Buenavista !( !( De 100 a 499 !. Más de 2,500 !( Tepeyac !(San Isidro !( !(Pie del Cerro Área Urbana La Cañada !( San José La Florecilla Unión Buenavista !( !. Amatenango del Valle !( San Gregorio Carreteras San Nicolás !( Federal Estatal 4 Carriles Cuota El Madronal )" COMITÁN DE Caminos DOMÍNGUEZ Nuevo Poblado el Sacrificio El Paraíso!( San José Cruz Quemada !( !(Tulanca !( Terracería Brecha Vereda Campo Grande !( !( !( Campo Alegre !( Estación Guadalupe Rancho Viejo !(El Rosario San Sebastián !( !(La Gloria !( !( Ríos N " N Los Cipreses Manzanillo " !( !(San Agustín 0 !( ' 0 ' !( Cruz Quemada 0 0 3 Perenne Intermitente ° 3 María Cristina!( ° San Carlos 6 6 1 1 Cuerpos de Agua San Miguel El Alto !( !(San Caralampio !(San Isidro Lindavista San Salvador Buenavista!( !(Candelaria Buenavista !(Santa Anita Benito Juárez !( !( Rancho Nuevo !(Monte Sinaí !(Nuevo Jerusalén !( !(Rancho Alegre Guadalupe Porvenir NOTAS: San Ramón Buenavista !( !(San José Yojulún Las localidades que no disponen de dato de número de habitantes corresponden a las localidades de nuevo registro identificadas por San Juan del Río II !( el INEGI en los trabajos de planeación de la Encuesta Intercensal !( San Juan del Río San José La Reforma !( 2015, pero que no fueron censadas durante dicho evento. -

Ley De Ingresos Para El Municipio De El Porvenir, Chiapas; Para El Ejercicio Fiscal 2011

Ley de Ingresos para el Municipio de El Porvenir, Chiapas; para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2011 Publicado, Periódico Oficial No. 276, Tercera Parte, de fecha 31 de Diciembre de 2010. Título Primero Impuestos Capítulo I Impuesto Predial Artículo 1. - El impuesto predial se pagará en la forma que a continuación se indica: I.- Predios con estudio técnico y base gravable determinada aplicando los valores unitarios aprobados por el H. Congreso del Estado para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2011, tributarán con las siguientes tasas: A) Predios urbanos. Tipo de predio Tipo de código Tasa Baldío bardado A 1.27 al millar Baldío B 5.05 al millar Construido C 1.27 al millar En construcción D 1.27 al millar Baldío cercado E 1.90 al millar B) Predios rústicos. Clasificación Categoría Zona Zona Zona homogénea 1 homogénea 2 homogénea 3 Riego Bombeo 1.52 0.00 0.00 Gravedad 1.52 0.00 0.00 Humedad Residual 1.52 0.00 0.00 Inundable 1.52 0.00 0.00 Anegada 1.52 0.00 0.00 Temporal Mecanizable 1.52 0.00 0.00 Laborable 1.52 0.00 0.00 Agostadero Forraje 1.52 0.00 0.00 Arbustivo 1.52 0.00 0.00 Cerril Única 1.52 0.00 0.00 Forestal Única 1.52 0.00 0.00 Almacenamiento Única 1.52 0.00 0.00 Extracción Única 1.52 0.00 0.00 Asentamiento humano Única 1.52 0.00 0.00 ejidal 1 1 Ley de Ingresos para el Municipio de El Porvenir, Chiapas; para el Ejercicio Fiscal 2011 Publicado, Periódico Oficial No. -

Notes on the Olvidado, Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico

Notes on the Olvidado, Palenque, Chiapas, Mexico PETER MATHEWS and MERLE GREENE ROBERTSON HARVARD UNIVERSITY and TULANE UNIVERSITY he Olvidado, or "Forgotten Temple," situated one- and proceed directly south to the Olvidado. Blom did half kilometer west of the Palace, was partially little more than draw a simple plan (1926, Vol. 1:Fig. T recorded by Heinrich Berlin in 1942. Nothing 157), note that the eastern end of the structure had already new has been published since then. A year and one-half fallen, and that it had "a roof ornament of unusual form." ago, a large portion of the roof of this temple collapsed, Heinrich Berlin, who visited this temple for the first endangering the rest of the building. Soon this important time in May 1940 gives a far more complete description temple, the earliest known standing architecture at Palen- (Berlin 1944), in fact, the only record until now of this que, will be gone forever. We felt that everything known small but vey important temple. He suggests an early about the temple should be recorded and made known epoch for the Olvidado, with several possible dates given immediately, so consolidating all of our previous notes, between 9.7.0.5.13 and 9.10.14.5.10. This will be dis- measurements, photographs, and other data from past cussed in this article when discussing the hieroglyphic years, we are presenting this report. When it became text on Piers A and D. known to us that this temple was indeed in danger of The Olvidado faces north, built along a steep escarp- completely collapsing, the two of us, Aucencio Cruz ment of the Sierra de Palenque mountain on a leveled-off Guzman, Lee Jones and Charlotte Alteri spent the better and filled-in portion of the slope. -

Amatenango Del Valle, Chiapas: Supervivencia De La Alfarería Prehispánica Zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbazyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcba

Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas: Supervivencia de la alfarería prehispánica zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA Sophia Pincemin zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA Instituto Chiapaneco de Cultura. Ponencia presentada en el 13° Congreso Internacional de Ciencias Antropológicas y Etnológicas. "Aunque las cerámicas de Yucatán resultan insignificantes en compara ción con la magnificencia de la arquitectura y de la escultura con las que están asociadas, son en un sentido real, la llave para descubrir la historia de los mayas yucatecos." (Brainerd, 1958: 1) El modelarunaarcillaplástica,secarlay luego cocerla para transformarla en una vasija, es un proceso generalizado en el mundo desde milenios. Como la cerámica es uno de los pocos elementos arqueológicos que puede sobrevivir relativamente bien al paso del tiempo y sus estragos, ha sido un material fundamental en el estudio de las antiguas civilizaciones: por ejemplo, podemos seguir el uso y desarrollo de las diferentes técnicas de ejecución y de la amplia variedad de motivos y dibujos sobre las vasijas, y todo ello nos puede dar información acercado la naturaleza de la sociedad en laque fueron hechas. La comunidad tzeltal de Amatenango del Valle, Chiapas, es una comunidad especializada en la fabricación de cerámica. Dicha fabricación queda todavía, páralos criterios modernistas, muy artesanal y hasta atrasada: no se utilizan el torno ni hornos de alta temperatura. Para el arqueólogo es una muestra viva de lo que pudo haber sido el trabajo de la cerámica en épocas anteriores. Localización El pueblodeAmatenangodel Valle se localiza en la zona de los Altos de Chiapas, en el centro del estado, a unos treinta kilómetros de la ciudad de San Cristóbal de Las Casas, a una altitud de 2 000 metros sobre el nivel el mar, está ubicado en un valle alargado que comunica con el de Teopisca y el de Aguacatenango, y cuenta con dos arroyos permanentes, el Amatenango y San Nicolás que provienen de dos ojos de agua. -

Indigenous Ecotourism in Preserving and Empowering Mayan Natural and Cultural Values at Palenque, Mexico

Indigenous Ecotourism in Preserving and Empowering Mayan Natural and Cultural Values at Palenque, Mexico Adrian Mendoza-Ramos and Heather Zeppel Abstract—Indigenous ecotourism in the Mayan Area has gone tourism throughout the world, and forecasted an average virtually unmentioned in the literature. As a result of the course of 4.2% annual increase for the next decade. of tourism in the Mayan Area, this study assessed the level of The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) empowerment in the Mayan communities surrounding a major defines indigenous communities, people, and nations as archaeological site and tourism attraction of the Classic Maya: those having “a historical continuity with pre-invasion and Palenque, in Mexico. The empowerment framework was used to pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, assess whether or not tourism develops in terms that ultimately are distinct from other settler groups and want to preserve, benefit the local communities economically, psychologically, politi- develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral cally, socially, and environmentally. A checklist of empowerment territories, and their ethnic identity” (UNDP 2004). This indicators identified from the literature were tested and contrasted historical continuity is based on occupation of ancestral with the interviews conducted with Mayan tourism stakeholders. lands, common ancestry, cultural practices, and language. Results indicate that local indigenous participation in tourism has Indigenous people are also economically and culturally not easily occurred due to a lack of knowledge of tourism and limited marginalized and often live in extreme poverty. They mainly economic resources and negotiation skills, which has significantly have a subsistence economy and rely on natural resources disempowered Mayan communities. -

Palenque and Selected Survey Sites in Chiapas and Tabasco: the Preclassic

FAMSI © 2002: Robert L. Rands Palenque and Selected Survey Sites in Chiapas and Tabasco: The Preclassic Research Year: 1998 Culture: Maya Chronology: Pre-Classic Location: Chiapas and Tabasco, México Sites: Palenque, Trinidad, Zapatilla, Chinikiha, Paso Nuevo Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Trinidad Zapatillo (Nueva Esperanza) Chinikiha Paso Nuevo Palenque Methodology and Closing Comments Key to Illustrations Illustrations Sources Cited Abstract Archaeological research focused on the major Classic Maya site of Palenque included the occasional recovery of Preclassic remains at various survey sites in Chiapas and Tabasco. Preclassic ceramics at four of these, in addition to Palenque, are considered. The Middle Preclassic is well represented at all sites, a primary subdivision being the appearance of waxy wares. The non-waxy to waxy shift, recalling Xe-Mamom relationships, is more pronounced than changes marking the Middle to Late Preclassic transition. Initial Middle Preclassic similarities tend to be stronger outside the Maya Lowlands than with other Lowland Maya sites, and a few ceramics also have non-Maya Early Preclassic correspondences. Depending in part on the survey site under consideration, Olmec/Greater Isthmiam features and Chalchuapa-like treatments are noted. Usually, however, relationships are observed on a modal rather than typological level, perhaps reflecting the reworking of external influences from varied sources and the occasional retention of earlier features as archaisms. Resumen La investigación arqueológica enfocada en el mayor sitio Maya Clásico de Palenque incluye la recuperación ocasional de restos Preclásicos en varios sitios examinados en Chiapas y Tabasco. Las cerámicas del Preclásico de cuatro de estos sitios, en adición al de Palenque, son también consideradas.