How Do Consultant Radiographers Contribute to Imaging Service Delivery and Leadership? Mapping Role Content Through Activity Diaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporting Radiographers: Hope Or Hype

Open Access Austin Journal of Radiology Review Article Reporting Radiographers: Hope or Hype Alahmari A* Department of Radiology, Al-Namas General Hospital, Abstract Saudi Arabia For more than 20 years and Reporting Radiographers practice exists in the *Corresponding author: Abdulwahab Alahmari, UK. Today no other country joined the UK to legislate Radiographers’ reporting Department of Radiology, Radiology Specialist, Al-Namas practice. The aim of this paper is to put a focus on the issue, look is there a General Hospital, Ministry of Health, Al-Namas City, necessity to allow Radiographers in the reporting business, and find is there Saudi Arabia any benefit that can change the decision of health authorities worldwide to allow Radiographers to make clinical reports. Received: February 22, 2021; Accepted: March 24, 2021; Published: March 31, 2021 Keywords: Reporting Radiographers; Radiology; Advanced Practice; Radiologists Introduction Radiographers can be specialized in chest x-ray reporting, abdomen x-ray reporting, and skeletal x-ray reporting for the The story of Radiographers report findings in radiographs when emergency. As well, reporting for ultrasound can be made by a Radiographers started using the “Red Dot” system which helps qualified Sonographer. Some curriculum of M.Sc. in Diagnostic Radiologists with an initial interpretation of any abnormality. In Imaging programs, (like the master’s degree in The University of World War II, there was a shortage of Radiologists to read the x-rays, Hertfordshire 2019 catalogue of post-graduate programs) which so Weber State University in collaboration with the US Army, trained contain a CT brain interpretation module. This program has an large numbers of Radiographers a.k.a “Radiologic Technologist in accreditation from the Society of Radiographers in the UK [4]. -

Questionnaire for Eiro Sectoral Representativeness Study on The

Questionnaire for Eiro sectoral representativeness study on the hospital sector UK : The representativeness of trade unions and employer associations in the hospital sector’. [Correspondent:] Length and format The responses of the national centres should be no longer than 2,500 words. Important: Please use this EIRO template questionnaire to respond, filling in the answer to each question underneath that question. Please also be reminded to fill in the metadata. Please retain all headings in the document. Do not change the text of the headings. You may add sub-headings if necessary. Please retain any text appearing in blue, which uses the ‘Comment Text’ paragraph style, as this will be automatically removed prior to publication. All other text (not in headings or in comments) will be retained and published online, so please ensure that it is suitable for publication. If you have any queries on administrative issues (deadlines, submission etc), please contact Alexandra Gryparis in the first instance. If you have any queries on the content of the information requested, please contact Franz Traxler ([email protected] ) and Georg Adam ([email protected] ) who are coordinating the study. [Correspondent:] Timing The deadline for the submission of responses by national centres is 4 December 2007. In order to fill in this questionnaire it is absolutely necessary to carefully read the accompanying guidelines (i.e. briefing note). The National Health Service (NHS) is by far the largest employer in the sector though there is a small, number of private companies running hospitals in the UK ( data on their employment is not available). -

Getting Into Research: a Guide for Members of the Society of Radiographers

Getting into Research: A Guide for Members of the Society of Radiographers Second edition November 2019 Review Date: November 2022 ISBN: 978-1-909802-46-9 Quartz House 207 Providence Square Mill Street London SE1 2EW 020 7740 7200 [email protected] www.sor.org Contents Glossary of acronyms and terms 3 Executive summary 4 Background 5 Research and members – the principles 6 Clinical audit and service evaluation 7 Getting started in research 8 Patient involvement 20 Involve 23 Finding funding 24 Getting help wth your research 31 Dissemination of results 32 Legal and compliance aspects of research 34 Summary 38 References 39 Appendix 1: Resources and Document Links 40 Appendix 2: Resources and Links Specific to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland 45 Appendix 3: Case Studies 47 GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS AND TERMS Below is a summary of acronyms and terms used in this guidance. Acronym Meaning AcoRD Attributing the costs of health and social care Research and Development AHP Allied Health Professional CAHPR Council for Allied Health Professions Research CI Chief Investigator CINAHL Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature CPD Continuing Professional Development CRF Case Report Form (or electronic CRF: eCRF) CRN Clinical Research Network (or local CRN: LCRN) DOI Digital Object Identifier EMBASE Excerpta Medica database FoRRM Formal Radiography Research Mentorship GCP Good Clinical Practice HCPC Health and Care Professions Council HRA Health Research Authority ICH GCP International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice IRAS -

Job Description and Person Specification

Job Description and Person Specification Job Title: Director of Industrial Strategy and Member Relations Hours of work: 1.0 whole time equivalent (35 hours per week) Contract: Permanent Line manager: Chief Executive Officer Place of Work: Head Office of the SoR, London Grade: Director Information about The Society and College of Radiographers are two separate companies the Society and operating together to provide service and support for those involved in College radiography. As a Group they enable the Society to fulfil its role as the professional body and trade union for those practicing in clinical imaging and radiotherapy while the science of radiography is advanced for the public benefit. The Society (SoR) is a Special Register trade union affiliated to the TUC with approximately 29,000 members. The College (CoR) is an independent charitable company registered in England and Scotland. The issued share capital of the College is owned by the Society. Although legally distinct companies, the Society and College operate in a seamless way and have common objectives concerned with the promotion and development of clinical imaging and radiotherapy, the promotion of study and research into radiography and the promotion of public awareness of the profession. All of these objectives are seen to be directly for the public benefit. As the trade union, the Society has the additional objective concerned with protecting the honour and interests of radiographers and others involved in the practice of radiography. This role reports entirely through the SoR. Job Purpose The role of Director of Industrial Strategy and Member Relations is a key member of the senior executive team, working closely with the Chief Executive Officer, two fellow Directors, the Presidential Team and the UK Council of the SoR. -

Newsletter Forum

isrrtisrrtisrrtNEWSLETTER Volume 46. No. 1 – 2010 InternationalInternational SocietySociety ofof RadiographersRadiographers andand RadiologicalRadiological TechnologistsTechnologists ISRRT Registered UK Charity - No. 276216 Contents Report RSNA: Imaging Through a Cross-cultural Lens: A Global Perspective on Values, Norms, Mystiques and Fears 10 TWSRT holds successful meeting 12 WHO Global Initiative on Radiation Safety in Health Care Settings Workshop on Second NIRS Kids Workshop 13 Cameroon Society of Medical Radiographers and Radiotherapist 8th Congress Report Meeting 14 Radiology Congress 26 Digital Radiography Summit 29 CAMRT report 31 Article A balancing act: potential benefits versus possible risks of radiation exposure 16 Interventional & Introperative MRI – from Canada to Asia & Beyond 22 The Role of Research in the Advancement of Health 28 News News from member societies: The Americas: Canada, Jamaic, Trinidad & Tobago 39 Asia/Australasia: Australia 41 Africa: South Africa 41 Europe: Cyprus, Greece, UK 42 Regulars President’s Message 3 Secretary General’s report 7 Contact details for: Submissions, deadlines, advertising & WRETF 8 Coming events 32 isrrt Councillor Profile: Rachel Bullard Editor: Aladdin Speelman 34 Production & Design: Deep Blue Design Studio, Jenny Motto 35 [email protected] WRETF Report 36 Printer: Geon Group ISSN NO. 1027-0671 Names and addresses of member societies & ISRRT Melbourne, Australia Council Members 44 The Board of Management of the ISRRT expresses ISRRT Officers of Board of Management 52 its appreciation to AGFA who generously support the production and distribution of the Newslettter. ISRRT Committees Regional Representatives 52 ISRRT Website: www.isrrt.org Volume 46 – No. 1 1 © 2008 Philips Electronics North America Corporation. Simplicity is education wherever and whenever you need it. -

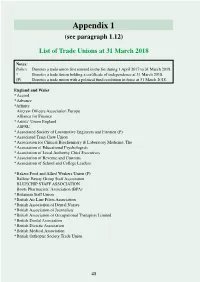

Appendix 1 (See Paragraph 1.12)

Appendix 1 (see paragraph 1.12) List of Trade Unions at 31 March 2018 Notes: Italics Denotes a trade union first entered in the list during 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018. * Denotes a trade union holding a certificate of independence at 31 March 2018. (P) Denotes a trade union with a political fund resolution in force at 31 March 2018. England and Wales * Accord * Advance *Affinity Aircrew Officers Association Europe Alliance for Finance * Artists’ Union England ASPSU * Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers and Firemen (P) * Associated Train Crew Union * Association for Clinical Biochemistry & Laboratory Medicine, The * Association of Educational Psychologists * Association of Local Authority Chief Executives * Association of Revenue and Customs * Association of School and College Leaders * Bakers Food and Allied Workers Union (P) Balfour Beatty Group Staff Association BLUECHIP STAFF ASSOCIATION Boots Pharmacists’ Association (BPA) * Britannia Staff Union * British Air Line Pilots Association * British Association of Dental Nurses * British Association of Journalists * British Association of Occupational Therapists Limited * British Dental Association * British Dietetic Association * British Medical Association * British Orthoptic Society Trade Union 48 Cabin Crew Union UK * Chartered Society of Physiotherapy City Screen Staff Forum Cleaners and Allied Independent Workers Union (CAIWU) * Communication Workers Union (P) * Community (P) Confederation of British Surgery Currys Supply Chain Staff Association (CSCSA) CU Staff Consultative -

Embedding Consultant Radiographer Roles Within Radiology Departments: a Framework for Success NIGHTINGALE, Julie, HARDY, M

Embedding consultant radiographer roles within radiology departments: a framework for success NIGHTINGALE, Julie, HARDY, M. and SNAITH, B. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/22068/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version NIGHTINGALE, Julie, HARDY, M. and SNAITH, B. (2018). Embedding consultant radiographer roles within radiology departments: a framework for success. Radiography, 24 (4), 289-297. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Embedding consultant radiographer roles within radiology departments: A framework for success J Nightingale; M Hardy; B Snaith Abstract Objectives: Many organisations struggle to clearly differentiate the radiographer consultant role from advanced or specialist practice, with newly appointed consultant practitioners often ill- prepared for working at this level. This article discusses the design, implementation and validation of an outcomes framework for benchmarking competencies for trainee or new-in-post consultant radiographers. Methods: Five experienced radiographers from different clinical specialisms were seconded to a twelve month consultant trainee post, guided by a locally-devised outcomes framework. A longitudinal qualitative study explored, from the radiographers' perspective, the impact of the outcomes framework on the transition to consultant practice and beyond. Data collection included semi-structured interviews (months 1, 6 and 12), validation via a focus group (month 18) and a group interview (5 years). Results: Early interactions with framework objectives were mechanistic, but as participants better understood the role more creative approaches emerged. -

Dear Colleague

WHC (2006) 083 WELSH HEALTH CIRCULAR Parc Cathays Cathays Park Caerdydd CF10 3NQ Cardiff CF10 3NQ Issue Date: 8th December 2006 Status: Information Title: Information Governance Process For Action by: Action required: None For Information to: See attached list Sender: Mr Gordon McKenzie, Head of Information Services Division, Resources Directorate, Health and Social Care Department, National Assembly for Wales National Assembly contact: Ruth Studley, Head of Information Standards, Resources Directorate, Health and Social Care Department, National Assembly for Wales Enclosure(s): Tel: 029 2082 5111 GTN: 1208 Llinell union/Direct line: 029 2082 6649 Ffacs/Fax: 029 2080 1188 http://howis.wales.nhs.uk/whcirculars.cfm Distribution List Chief Executives NHS Trusts Chief Executives Local Health Boards Director Welsh NHS Confederation Chief Officer Association of Welsh Community Health Councils Director Welsh Local Government Association Dean University of Wales, Bangor Chief Executive Commission for Racial Equality Secretary British Dental Association in Wales Postgraduate Dean University of Wales College of Medicine Director of Information Services University of Wales College of Medicine Secretary British Medical Association (Wales) Regional Head of Health UNISON Board Secretary Royal College of Nursing (Wales) Welsh Council Representative British Dietetic Association Wales Secretary British Orthoptic Society Wales Secretary AMICUS MSF Regional Secretary The GMB Regional Secretary Transport & General Workers Union Chair Community Pharmacy Wales -

Taxpayer Funding of Trade Unions 2012-13

Research Note 140 | 10 September 2014 Taxpayer funding of trade unions 2012-13 Last year Cabinet Office Minister Francis Maude announced plans to reduce the amount of facility time taken by Civil Servants on Whitehall. This will cut the subsidy that unions receive at taxpayers’ expense. There is still be a substantial subsidy however, and the reforms do not yet apply to the broader public sector. As of April 2013, the Cabinet Office has been publishing facility time figures for central government departments online, an encouraging step towards transparency. Earlier TaxPayers’ Alliance research in this area revealed the extent of trade union subsidies across the public sector for the first time. This research updates that evidence of the huge amounts of taxpayers’ money given to trade unions through direct funding or paid staff time from public sector bodies. It contains information about the number of public sector bodies automatically deducting trade union subscriptions in the payroll process, often without charging the unions for that additional administrative support. The key findings of this research are: . Trade unions received a subsidy of at least £108 million at taxpayers’ expense in 2012-13. This is made up of an estimated £85 million in paid staff time, plus £23 million in direct payments. At least 2,841 full-time equivalent (FTE) public sector staff worked on trade union duties at taxpayers’ expense in 2012-13. The number of full-time equivalent staff provided to trade unions is 2.5 times as large as the workforce of HM Treasury.1 . 344 public sector organisations (out of the 1,074 surveyed) either did not fully record facility time or did not record it at all in 2012-13. -

Labour Relations Also L!Y Frank Burchiu

Labour Relations Also l!y Frank BurchiU HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT The NHS: A Case Study (with Alice Casey) Labour Relations Second Edition Frank Burchill C) Frank Burchill 1992, 1997 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with * the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, london W1 P OlP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First edition 1992 Reprinted twice Second edition 1997 Published by PAlGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin's Press lLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers ltd (formerly Macmillan Press ltd). ISBN 978-0-333-69521-0 ISBN 978-1-349-14497-6 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-14497-6 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

NHS Trade Unions Working Together to Improve NHS Pay

NHS trade unions working together to improve NHS pay Staff Side Evidence to the NHS Pay Review Body 2018-191 Summary and recommendations The value of the Agenda for Change pay framework has diminished significantly over the last seven years, with NHS staff suffering a real terms fall in earnings of between 10 and 20%. There is now a consensus across most political parties, economists and NHS employer bodies that the pay cap must be lifted. NHS staff must be awarded a meaningful pay rise which starts to restore lost earnings, keeps up with the ever rising cost of living and enables the recruitment and retention of a highly skilled and motivated workforce. We are calling for a fully funded UK-wide pay settlement which will: 1) Enable NHS staff to keep up with costs by matching RPI inflation 2) Start to restore pay lost during the years of austerity, giving a consolidated sum of £800 to all 3) Invest in improving the NHS pay structure, making it better able to support workforce productivity improvements These proposals were clearly set out in a joint staff side letter to the Chancellor of the Exchequer in September 2017 (see appendix). The principles underpinning this three-part claim are that sufficient additional funding should be provided by Government with spending spread between real pay uplifts, restorative awards, and funding a restructure in line with the NHS trade unions’ preferred pay system. The NHS trade unions have commissioned an independent body to cost our claim for 2018-19. Incomes Data Research demonstrate that the claim would cost approximately £2.2 billion, an increase of approximately 6.3% to the non-medical paybill. -

Nominating Bodies This Details the Names of the Associations Or

Nominating bodies This details the names of the associations or organisations that we have listed to send information about nominating panel members or assessors for REF. However, any association or organisation with an interest in the conduct, quality, funding or use of research may make nominations to the REF panels (except individual UK HEIs, groups within or subsidiaries of individual HEIs, and HE mission groups). Associations or organisations with an interest in research who are not on this list, and who would like to receive information in future about nominating panel members and assessors, should contact [email protected].