The Fight for Mauna Kea," Spectrum: Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Hawaii Telescopes at Mauna Kea Observatory

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII TELESCOPES AT MAUNA KEA OBSERVATORY USER MANUAL Fourth Edition, April 1996 Last modi®ed, June 1997 Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 1 1.2 About this Manual :: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 1 1.3 Observing TimeÐPolicy and Procedures : :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 1 1.3.1 Students and Assistants :: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.2 Information before Arrival : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.3 Colloquia :: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.4 Reports to the Director ::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.3.5 Publications and Acknowledgments ::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 3 1.4 Newsletter :: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 4 1.5 Information for Visiting Observers : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 4 1.5.1 Transportation from Hilo to Hale Pohaku and Mauna Kea Observatory :: :::: ::: :::: : 4 1.6 AccommodationÐThe Mid-level Facility, Hale Pohaku :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 1.6.1 Telephone Service : :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 1.6.2 Mail Service : ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 1.6.3 Library :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 8 2 VISITING OBSERVER EQUIPMENT 11 2.1 Packing Goods for Shipping :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: : 11 2.2 Transport ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: :::: ::: -

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

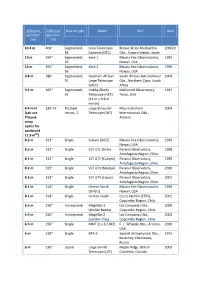

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

![Arxiv:2009.11049V2 [Astro-Ph.IM] 24 Sep 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5003/arxiv-2009-11049v2-astro-ph-im-24-sep-2020-1375003.webp)

Arxiv:2009.11049V2 [Astro-Ph.IM] 24 Sep 2020

Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics manuscript no. (LATEX: ms2020-0197.tex; printed on September 25, 2020; 1:02) The estimate of sensitivity for large infrared telescopes based on measured sky brightness and atmospheric extinction Zhi-Jun Zhao1,4, Hai-Jing Zhou1, Yu-Chen Zhang2, Yun Ling3 and Fang-Yu Xu∗2 1 School of Physics, Henan Normal University,Xinxiang 453007, China; xu [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Yunnan Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650216, China; 3 Kunming Institute of Physics, Kunming 650216, China; 4 Henan Key Laboratory of Infrared Materials & Spectrum Measures and Applications, Xinxiang 453007, China Received 20xx month day; accepted 20xx month day Abstract : In order to evaluate the ground-based infrared telescope sensitivity affected by the noise from the atmosphere, instruments and detectors, we construct a sensitivity model that can calculate limiting magnitudes and signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). The model is tested with tentative measurements of M′-band sky brightness and atmospheric extinction obtained at the Ali and Daocheng sites. We find that the noise caused by an excellent scientific detector and instruments at 135◦C can be ignored compared to the M′-band sky background noise. − Thus, when S/N =3 and total exposure time is 1 second for 10 m telescopes, the magnitude limited by the atmosphere is 13.01m at Ali and 12.96m at Daocheng. Even under less-than- − arXiv:2009.11049v2 [astro-ph.IM] 24 Sep 2020 ideal circumstances, i.e., the readout noise of a deep cryogenic detector is less than 200e and the instruments are cooled to below 87.2◦C, the above magnitudes decrease by 0.056m − at most. -

Minutes Regular Meeting Mauna Kea Management Board Wednesday

University of Hawai‘i at Hilo 640 N. A‘ohoku Place, Room 203, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720 Telephone: (808) 933-0734 Fax: (808) 933-3208 Mailing Address: 200 W. Kawili Street, Hilo, Hawai‘i 96720 Minutes Regular Meeting Mauna Kea Management Board Wednesday, May 19, 2010 ʻImiloa Astronomy Center Moana Hoku Hall 600 ʻImiloa Place Hilo, Hawaii 96720 Attending MKMB: Chair Barry Taniguchi, 2nd Vice Chair/Secretary Ron Terry, John Cross, Lisa Hadway, Herring Kalua, and Christian Veillet BOR: Dennis Hirota and Eric Martinson Kahu Kū Mauna: Ed Stevens OMKM: Stephanie Nagata and Dawn Pamarang Others: Robert Albarson, Jim Albertini, Laura Aquino, Dean Au, Madeline Balo-Keawe, Sean Bassle- Kukonu, David Byrne, Rob Christensen, Gregory Chun, Nan Chun, Vaughn Cook, Sandra Dawson, Donn delaCruz, Gerald DeMello, Richard Dods, Suzanne Frayser, Paul Gillett, MRC Greenwood, Richard Ha, Katherine Hall, Cory Harden, Inge Heyer, Clyde Higashi, Nelson Ho, Arthur Hoke, Jacqui Hoover, Stewart Hunter, Stew Hussey, Leslie Isemoto, Mark Ishii, Paul Kagawa, Mike Kaleikini, Ka’iu Kimura, Kyle Kinoshita, Ron Koehler, Randy Kurohara, Susan Law, Tim Law, Karina Leasure, Jonathan Lee, Pete Lindsey, George Martin, Tani Matsubara, Jeff Melrose, Jon Miyata, Delbert Nishimoto, Eugene Nishimura, James Nixon, Cynthia Nomura, Alton Nosaka, Derek Oshita, Tom Peek, Koa Rice, Helen Rogers, Skylark Rossetti, Gary Sanders, Ian Sandison, Bill Stormont, Leonard Tanaka, Rose Tseng, Ross Watson II, Josh Williams, Ross Wilson, Greg Wines, Harry Yada, Mason Yamaki, Miles Yoshioka I. CALL TO ORDER Chair Taniguchi called the meeting of the Mauna Kea Management Board (MKMB) to order at 9:03 a.m. II. APPROVAL OF MINUTES Upon motion by Herring Kalua and seconded by Ron Terry the minutes of the April 21, 2010 meeting of the MKMB were unanimously approved. -

The International Gemini Telescopes Project Has Made Giant Steps Forward, Despite Having Undergone Considerable Reassessment

THETHE GEMINIGEMINIINTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL AnnualAnnual TELESCOPESTELESCOPES ReportReport 19951995 United States United Kingdom Canada Chile Brazil Argentina The photographs above show the first primary mirror at the Corning plant at Canton, NY, at the completion ceremony in October 1995, and the mirror being loaded onto a barge at Odgensburg Port on the St. Lawrence Seaway in December 1995, en route to the REOSC polishing plant in France. The cover photographs show (above) the Gemini site at Mauna Kea in October 1995 with the University of Hawaii telescope in the background, and (below) at Cerro Pachón in December 1995. Photograph credits: Susan Kayser, the International Gemini Project Office The Annual Report for 1995 was prepared by the National Science Foundation, the Executive Agency for the International Gemini 8-Meter Telescopes Project. Gemini Project Annual Report 1995 Message from the Gemini Board ...................................................................................................................... ii Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Schedule............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Organization ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Gemini -

The Mauna Kea Observatories Near-Infrared Filter Set. II. Specifications for a New JHKL!

Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 114:180–186, 2002 February ᭧ 2002. The Astronomical Society of the Pacific. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. The Mauna Kea Observatories Near-Infrared Filter Set. II. Specifications for a New JHKLЈMЈ Filter Set for Infrared Astronomy A. T. Tokunaga Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822; [email protected] D. A. Simons Gemini Observatory, Northern Operations Center, 670 North A‘ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720; [email protected] and W. D. Vacca Max-Planck-Institut fu¨r extraterrestrische Physik, Postfach 1312, D-85741 Garching, Germany; [email protected] Received 2001 July 28; accepted 2001 October 17 ABSTRACT. We present a description of a new 1–5 mm filter set similar to the long-used JHKLM filter set derived from that of Johnson. The new Mauna Kea Observatories Near-Infrared filter set is designed to reduce background noise, improve photometric transformations from observatory to observatory, provide greater accuracy in extrapolating to zero air mass, and reduce the color dependence in the extinction coefficient in photometric reductions. We have also taken into account the requirements of adaptive optics in setting the flatness specification of the filters. A complete technical description is presented to facilitate the production of similar filters in the future. 1. INTRODUCTION baru Telescopes, all of the optical/infrared observatories at Mauna Kea are currently using these filters (NASA Infrared The rationale for a new set of infrared filters was presented Telescope Facility, United Kingdom Infrared Telescope, Canada- by Simons & Tokunaga (2002, hereafter Paper I). -

Mauna Kea Public Access Plan January 2010

PUBLIC ACCESS PLAN FOR THE UH MANAGEMENT AREAS ON MAUNA KEA A Sub-Plan of the Mauna Kea Comprehensive Management Plan January 2010 Prepared for: Office of Mauna Kea Management University of Hawai‘i-Hilo 200 W. Kawili Street Hilo, Hawaii 96720 Prepared by: Sustainable Resources Group Intn’l, Inc. Island Planning Island Transitions, LLC 111 Hekili Street, Suite A373 1405 Waianuenue Avenue P.O. Box 202 Kailua, HI 96734 Hilo, HI 96720 Pa‘auilo, HI 96776 Acknowledgements The Public Access Plan was funded by the Office of Mauna Kea Management (OMKM). Interim Director Stephanie Nagata was instrumental in setting up and overseeing all aspects of the contract with Sustainable Resources Group Intn’l Inc (SRGII). She provided critical reviews of plan drafts and insight to the operational history and current policies that have shaped activities in the UH Management Areas on Mauna Kea over the years. Ms. Nagata and her assistant, Dawn Pamarang, were of great assistance throughout the project. Special appreciation is due to several groups and individuals. Members of Kahu Kū Mauna generously contributed their time as a group and in subcommittee and roundtable discussions to assist in this planning process. David Byrne, Visitor Information Station (VIS) Supervisor, was readily available and enabled his staff to meet with the planners, resulting in better understanding of the ranger program, daily operations at the VIS and appreciation of how the current management of public use on the mountain has evolved over the years. The Mauna Kea Rangers, both past and present, shared quality data, observations, suggestions and concerns that can only come from daily interactions with the public on Mauna Kea. -

Big Glass and the Age of New Astronomy | Space | Air & Spac

Big Glass and the Age of New Astronomy | Space | Air & Spac... http://www.airspacemag.com/space/big-astronomy-how-built-1... AirSpaceMag.com Big Glass and the Age of New Astronomy The fight to put a monster telescope on Mauna Kea is part of a bigger war looming among astronomers. By Dennis Hollier Air & Space Magazine | Subscribe September 2016 The tallest island mountain in the world is Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, where the thin atmosphere and absence of light pollution create some of the best observing conditions for astronomers. At the summit, 13 telescopes sit along a ridge of formations that have built up around volcanic vents. The oldest telescope on site, and still the smallest, is the University of Hawaii’s 2.2-meter (7.2-foot) UH88, built in 1968. Mauna Kea is best known as the home of the twin 10-meter Keck telescopes, which saw first light in the 1990s and remain two of the largest optical and infrared telescopes in the world. Collectively, this baker’s dozen of observatories has dominated ground-based astronomy for four decades. But recently, Mauna Kea has become embroiled in a dispute that could radically alter the future of astronomy, and serve as a cautionary example of what we might lose if it keeps going down this path. In 2009, Mauna Kea was chosen as the site for the Thirty Meter Telescope, a mega-observatory proposed by the California Institute of Technology, the University of California, and national science agencies in Japan, Canada, India, and China. Its massive mirror will be made from 492 segments and have 81 times the sensitivity of the Keck telescopes. -

MKCMP Decommissioning Plan for Mauna Kea Observatories

DECOMMISSIONING PLAN FOR THE MAUNA KEA OBSERVATORIES A Sub-Plan of the Mauna Kea Comprehensive Management Plan January 2010 Prepared for: Office of Mauna Kea Management University of Hawai‘i-Hilo Prepared by: Sustainable Resources Group Intn’l, Inc. DECOMMISSIONING PLAN FOR THE MAUNA KEA OBSERVATORIES A Sub-Plan of the Mauna Kea Comprehensive Management Plan January 2010 Prepared for: Office of Mauna Kea Management University of Hawai‘i - Hilo 200 W. Kawili Street Hilo, Hawaii 96720 www.malamamaunakea.org Prepared by: Sustainable Resources Group Intn’l, Inc. 111 Hekili Street, Suite A373 Kailua, HI 96734 www.srgii.com Executive Summary The Decommissioning Plan for Mauna Kea Observatories (Decommissioning Plan) is a sub-plan of the Mauna Kea Comprehensive Management Plan (CMP). It was required as a condition of approval of the CMP by the Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) in April 2009. The purpose of this Decommissioning Plan is to describe a process for decommissioning observatories on Mauna Kea, including financial planning. Although some observatories have made preliminary inquiries regarding what might be expected of them if they were to cease operations, neither the State, nor the University, have guidelines for the decommissioning of facilities. This Decommissioning Plan provides the guidelines recommended by the University. The Decommissioning Plan provides a framework that can be used by both existing and future observatories on Mauna Kea to ensure that the Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) as the land owner and lessor, UH as the lessee, and the observatories as sublessees have clear expectations of the observatory decommissioning process. -

Board of Land and Natural Resources’ Own Findings of Fact Or Conclusions of Law Or Decision and Order, And/Or

______________________________________________________________________________________ uoH • BOARD OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES 3 II3 2 P STATE OF HAWAII In re Petitions Requesting a Contested ) DLNR Dock Case Hearing Re Conservation District Use) Permit (CDUP) HA-3568 for the Thirty ) FINDINGS OF FACT, Meter Telescope at the Mauna Kea Science) CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND Reserve, Ka’ohe Mauka, Hamakua District,) DECISION AND ORDER; Island of Hawai’i, TMK (3) 4-4-01 5:009 ) CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ) ) FINDINGS OF FACT, CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND DECISION AND ORDER This contested case hearing involves Conservation District Use Application (“CDUA”) HA-3568 for the Thirty Meter Telescope at the Mauna Kea Science Reserve. The following Findings of Fact, (“FOF”), Conclusions of Law (“COL”), and Decision and Order are based on the records maintained by the Department of Land and Natural Resources on CDUA HA-3568 and the witness testimonies and exhibits presented and accepted into evidence. If any statement denominated a COL is more properly considered a FOF, then it should be treated as a FOF; and conversely, if any statement denominated as a FOF is more properly considered a COL, then it should be treated as a COL. Any proposed finding of fact submitted by the parties which is not specifically incorporated above is rejected for one or more of the following reasons: 1. They are repetitious or similar to the Board of Land and Natural Resources’ own findings of fact or conclusions of law or decision and order, and/or 2. They are not supported by the reliable and/or probative evidence, and/or 3. -

Abby Herhold Mauna Kea Thesis Final

Hawai’i’s Thirty Meter Telescope Construction of the World’s Largest Telescope on a Sacred Temple Abby Starr Herhold Master thesis in Culture, Environment and Sustainability Centre for Development and Environment UNIVERSITY OF OSLO October 2015 II © Abby Starr Herhold October 2015 Hawai’i’s Thirty Meter Telescope: Construction of the World’s Largest Telescope on a Sacred Temple http://www.duo.uio.no/ Print: Reprosentralen, University of Oslo III Abstract Mauna Kea is located on the Big Island of Hawai’i. It is a dormant volcano and the highest mountain in the world measured from sea bottom. Mauna Kea’s dry atmosphere, cloud-free skies and distance from city lights attracted astronomers starting in the1960s. The first telescope was built on the summit in 1970. Since then there has been a total of 13 telescopes built on Mauna Kea, funded by 11 different countries (Astronomy 2014). Mauna Kea is considered to be the preeminent site in the world for ground-based astronomy. On April 12, 2013, the Thirty Meter Telescope Observatory Corporation was granted a Conservation District Use Permit (CDUP) by the Hawai’i Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) to build and operate the US $1.4 billion Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) on Mauna Kea. The TMT will have the most advanced technology of any telescope on Earth, far surpassing the orbiting Hubble telescope’s capabilities (TMT 2015). The potential for scientific discovery is enormous. Paradoxically, Mauna Kea is also considered to be the most sacred place in all of Hawai’i for Native Hawaiian people. -

Communications Challenge for the Gemini 8-M Telescopes

Communications challenge for the Gemini 8-m Telescop es James R. Wright Gemini 8-m Telescop es Pro ject 950 North Cherry Avenue Tucson, Arizona 85726-6732 USA ABSTRACT We discuss the requirements and design of the communications system for the Gemini 8-meter Telescop es Pro ject . This system is unique not only in our integrated approach to data, voice and video, but it also must span the glob e to reach the two telescop e sites in Chile and Hawaii, and provide access to astronomers around the world. We discuss the various services planned for the communications system, the many lo cations whichmust b e served, and the anticipated quality-of-service demands. The constraints which limit our options are also discussed. Finally we present our plans for meeting these challenges. Keywords: communications, LAN, WAN, video conferencing, telephony, ethernet, ATM 1. INTRODUCTION The Gemini Pro ject is an international partnership to build two 8-meter telescop es, one on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, and one on Cerro Pachon, Chile. The telescop es and auxiliary instrumentation will b e international facilities op en to the scienti c communities of the memb er countries. The pro ject includes not only the summit lo cations for the actual telescop es, but also base facilities in Hilo, Hawaii and La Serena, Chile; mid-level facilities at Hale Pohaku, Hawaii and Cerro Tololo, Chile; an International Pro ject Oce at a lo cation to b e determined; National Pro ject Oces in each memb er country; and all the home institutions for the user community.