Funeral Monuments in Macedonia During the Archaic and Classical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luxury Board Games for the Northern Greek Elite Despina Ignatiadou

Luxury Board Games for the Northern Greek Elite Despina Ignatiadou To cite this version: Despina Ignatiadou. Luxury Board Games for the Northern Greek Elite. Archimède : archéologie et histoire ancienne, UMR7044 - Archimède, 2019, pp.144-159. halshs-02927454 HAL Id: halshs-02927454 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02927454 Submitted on 1 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N°6 ARCHÉOLOGIE ET HISTOIRE ANCIENNE 2019 1 DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE : HISTOIRES DE FIGURES CONSTRUITES : LES FONDATEURS DE RELIGION DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE : JOUER DANS L’ANTIQUITÉ : IDENTITÉ ET MULTICULTURALITÉ GAMES AND PLAY IN ANTIQUITY: IDENTITY AND MULTICULTURALITY 71 Véronique DASEN et Ulrich SCHÄDLER Introduction EGYPTE 75 Anne DUNN-VATURI Aux sources du « jeu du chien et du chacal » 89 Alex DE VOOGT Traces of Appropriation: Roman Board Games in Egypt and Sudan 100 Thierry DEPAULIS Dés coptes ? Dés indiens ? MONDE GREC 113 Richard. H.J. ASHTON Astragaloi on Greek Coins of Asia Minor 127 Véronique DASEN Saltimbanques et circulation de jeux 144 Despina IGNATIADOU Luxury Board Games for the Northern Greek Elite 160 Ulrich SCHÄDLER Greeks, Etruscans, and Celts at play MONDE ROMAIN 175 Rudolf HAENSCH Spiele und Spielen im römischen Ägypten: Die Zeugnisse der verschiedenen Quellenarten 186 Yves MANNIEZ Jouer dans l’au-delà ? Le mobilier ludique des sépultures de Gaule méridionale et de Corse (Ve siècle av. -

For Municipal Solid Waste Management in Greece

Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity Article Description and Economic Evaluation of a “Zero-Waste Mortar-Producing Process” for Municipal Solid Waste Management in Greece Alexandros Sikalidis 1,2 and Christina Emmanouil 3,* 1 Amsterdam Business School, Accounting Section, University of Amsterdam, 1012 WX Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2 Faculty of Economics, Business and Legal Studies, International Hellenic University, 57001 Thessaloniki, Greece 3 School of Spatial Planning and Development, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 54124 Thessaloniki, Greece * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-2310-995638 Received: 2 July 2019; Accepted: 19 July 2019; Published: 23 July 2019 Abstract: The constant increase of municipal solid wastes (MSW) as well as their daily management pose a major challenge to European countries. A significant percentage of MSW originates from household activities. In this study we calculate the costs of setting up and running a zero-waste mortar-producing (ZWMP) process utilizing MSW in Northern Greece. The process is based on a thermal co-processing of properly dried and processed MSW with raw materials (limestone, clay materials, silicates and iron oxides) needed for the production of clinker and consequently of mortar in accordance with the Greek Patent 1003333, which has been proven to be an environmentally friendly process. According to our estimations, the amount of MSW generated in Central Macedonia, Western Macedonia and Eastern Macedonia and Thrace regions, which is conservatively estimated at 1,270,000 t/y for the year 2020 if recycling schemes in Greece are not greatly ameliorated, may sustain six ZWMP plants while offering considerable environmental benefits. This work can be applied to many cities and areas, especially when their population generates MSW at the level of 200,000 t/y, hence requiring one ZWMP plant for processing. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Stamelou Afrodite

The Poly-SUMP methodology as a tool for sustainable urban mobility planning. The case of Central Macedonia Region in Greece Stamelou Afrodite MSc Civil Engineer - Transportation Planner MSc Environmental Protection & Sustainable Development Bulgaria, 18-19 March 2015 ANATOLIKI S.A. - Development Agency of Eastern Thessaloniki’s Local Authority ANATOLIKI S.A. was established on 1995 ANATOLIKI S.A. is active in the following sectors: Environment and infrastructures Energy Saving and RES Human Resources Local Authorities and Business Support Rural Development Promotion of innovation and New technologies Support in Networks Operation I 2 ANATOLIKI S.A. - Development Agency of Eastern Thessaloniki’s Local Authority The shareholders of ANATOLIKI S.A. are: Region of Central Macedonia Local business Associations and Cooperatives Nine (9) Municipalities • Municipality of Kalamaria • Greek association of women • Municipality of Pylaia-Hortiati entrepreneurs • Municipality of Volvi • Business association of Thessaloniki & • Municipality of Thessaloniki Chalkidiki • Municipality of Thermi • Professionals’ & manufacturers’ • Municipality of Nea Propontida association of Mihaniona • Municipality of Polygyros • Agricultural cooperative of Vasilika • Municipality of Neapoli – Sykιes • Agricultural cooperative of Thermi • Municipality of Thermaikos • Agricultural cooperative of Triadi • Quarries' productive cooperative “Kypseli” Chambers • Agricultural cooperative of Petrokerasa • Chamber of small & medium sized industries of “Agia Trias” Thessaloniki -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000-700 BCE Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8588693d Author Kontonicolas, MaryAnn Emilia Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000 – 700 BCE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology by MaryAnn Kontonicolas 2018 © Copyright by MaryAnn Kontonicolas 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000 – 700 BCE by MaryAnn Kontonicolas Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor John K. Papadopoulos, Chair This research project examines the appearance and proliferation of some of the earliest cremation burials in Europe in the context of the prehistoric north Aegean. Using archaeological and osteological evidence from the region between the Pindos mountains and Evros river in northern Greece, this study examines the formation of death rituals, the role of landscape in the emergence of cemeteries, and expressions of social identities against the backdrop of diachronic change and synchronic variation. I draw on a rich and diverse record of mortuary practices to examine the co-existence of cremation and inhumation rites from the beginnings of farming in the Neolithic period -

The Religious Tourism As a Competitive Advantage of the Prefecture of Pieria, Greece

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management, May-June 2021, Vol. 9, No. 3, 173-181 doi: 10.17265/2328-2169/2021.03.005 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Religious Tourism as a Competitive Advantage of the Prefecture of Pieria, Greece Christos Konstantinidis International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece Christos Mystridis International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece Eirini Tsagkalidou Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece Evanthia Rizopoulou International Hellenic University, Serres, Greece The scope of the present paper is the research of whether the prefecture of Pieria comprises an attractive destination for religious tourism and pilgrimage. For this reason, the use of questionnaires takes place which aims to realizing if and to what extend this form of tourism comprises a comparative and competitive advantage for the prefecture of Pieria. The research method of this paper is the qualitative research and more specifically the use of questionnaires with 13 questions in total. The scope was to research whether the prefecture of Pieria is a religious-pilgrimage destination. The sample is comprised of 102 participants, being Greek residents originating from other Greek counties, the European Union, and Third World Countries. The requirement was for the participant to have visited the prefecture of Pieria. The independency test (x2) was used for checking the interconnections between the different factors, while at the same time an allocation of frequencies was conducted based on the study and presentation of frequency as much as relevant frequency. Due to the fact that, no other similar former researches have been conducted regarding religious tourism in Pieria, this research will be able to give some useful conclusions. -

List of Designated Points of Import in Greece

List of Designated Points of Import for Food in Greece 1. Port of Pireus . Warehouse PCDC, Pireus Consolidation and Distribution Center, N.Ikonio, Perama Attikis . Warehouse C4, Pireus Port Authority SA, N.Ikonio, Perama Attikis . Warehouse C3 and C5 of Pireus Port Organisation SA, Keratsini Attikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Attiki tel: (+30) 2104002850 / 2104326819/ 2104000219 Fax: (+30) 2104009997 email: [email protected] 2 Athens International Airport “Eleftherios Venizelos” Building 26A, Athens International Airport, Spata Attikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Attiki tel: (+30) 2103538456 / 2104002850 / 2104326819/ 2104000219 Fax: (+30) 2103538457, 2104009997 email: [email protected] / [email protected] 3 Athens Customs of Athens, Metamorfosi Attikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Attiki tel: (+30) 2104002850 / 2104326819/ 2104000219 Fax: (+30) 2104009997 email: [email protected] 4 Port of Thessaloniki APENTOMOTIRIO, 26th Octovriou, Gate 12, p.c.54627, Organismos Limena Thessalonikis CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Thessaloniki tel: (+30) 2310547749 Fax: (+30) 2310476663 / 2310547749 email: [email protected] 5 Thessaloniki International Airport “Makedonia” Thermi, Thessaloniki CA: Regional Center for Plant Protection, Quality and Phytosanitary Control of Thessaloniki tel: (+30) 2310547749 Fax: (+30) 2310476663 / 2310547749 email: -

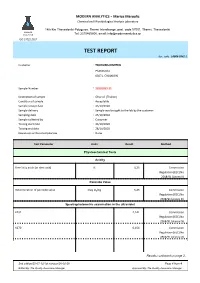

TEST REPORT Doc

MODERN ANALYTICS - Marios Maroulis Chemical and Microbiological Analysis Laboratory 14th Km Thessaloniki-Polygyros, Thermi Interchange, post. code 57001, Thermi, Thessaloniki MODERN ANALYTICS Tel: 2310465600, email: [email protected] ISO 17025:2017 TEST REPORT doc. code : LAB06-03#2-1 Customer : TSIKOURIS DIMITRIS PSAKOUDIA 63071, CHALKIDIKI Sample Number : 20201023-21 Description of sample : Olive oil [Thallon] Condition of sample : Acceptable Sample receipt date : 23/10/2020 Sample delivery : Sample was brought to the lab by the customer Sampling date : 23/10/2020 Sample collected by : Customer Testing start date : 23/10/2020 Testing end date : 26/10/2020 Deviations or Non-Compliances : None Test Parameter Units Result Method Physicochemical Tests Acidity Free fatty acids (as oleic acid) % 0,23 Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 (Annex II) Peroxide Value Determination of peroxide value meq O₂/Kg 6,46 Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 (Annex III) Spectrophotometric examination in the ultraviolet Κ232 2,141 Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 (Annex IX) Κ270 0,154 Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 (Annex IX) Results continued on page 2... 2nd edition/25-07-12/1st revision/20-02-20 Page 1 from 4 Edited By: The Quality Assurance Manager Approved By: The Quality Assurance Manager MODERN ANALYTICS - Marios Maroulis Chemical and Microbiological Analysis Laboratory 14th Km Thessaloniki-Polygyros, Thermi Interchange, post. code 57001, Thermi, Thessaloniki MODERN ANALYTICS Tel: 2310465600, email: [email protected] -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

This Entire Document

THEBT THI FPOHTINQ LirR FuBLicniNO Co. SPORTING LIFEESTERED AT Pill LA. POST OFFICE AS SECOND CLASS MATTER. VOLUME 12, NO. 23. PHILADELPHIA, PA., MARCH 13, 1889. PRICE, FIVE CENTS. ml tbe first gaane* will b« played at Waco, Fort liamfata. Not much jjood even in the Wtstern Asso- Worth and floudtoa. It baa been so arranged that ritttion. An>1 as it is pretty near time for the pu- ssinjr. there will bo no lay-offs. bee to begin 1 will tUit tbe ball YolHug. First, MiL- LATE_NEWS. neapolis (of course) or St. Paul; second, the earn*-; THE GUEAT TRIP. Pitcher. thTd, Omaha; fourth, Milwaukee; fifth, St. Jo?; sixth; A New Newark Des Moiiies; seventh, Sioux City; eighth, Denver. Special 10 SrOBTixo Lin. Suppose there thcuM be a nip-aud-tuck ruht for A Bad Case Against Two NKWARK, N. J., March 9. Vownrk has signed II. D. first place between ihe twos, what a fat thni£ it Travis, ut Cap* Charles, and expects we inters of him as would be for Blorton and Barncs. Wo would have The Spalding Tourists in a pirchor. He itaoda aix luot and tbrett inched In hia 5,000 people every day. Ball Players. bare fe*-t aud is tuilt m proportion, lie has a speedy The team will report early this month nnd practice iu tbe athletic club ^yinuailuiu until tho ground tibd Merry France. weather jiermit outside work. HARTFORD STILT. HUSTLING. Season tickets Lave been placed on pale and already THE OLD "WETS'" REORGAN a number have been sold. They cfat 620 each. -

Technical Report Skouries Project Greece

Technical Report Skouries Project Greece Centered on Latitude 40° 29’and Longitude 23°42’ Effective Date: January 01, 2018 Prepared by: Eldorado Gold Corporation 1188 Bentall 5 - 550 Burrard Street Vancouver, BC V6C 2B5 Qualified Person Company Mr. Richard Alexander, P.Eng. Eldorado Gold Corporation Dr. Stephen Juras, P.Geo. Eldorado Gold Corporation Mr. Paul Skayman, FAusIMM Eldorado Gold Corporation Mr. Colm Keogh, P.Eng. Eldorado Gold Corporation Mr. John Nilsson, P.Eng. Nilsson Mine Services Ltd. S KOURIES P ROJECT, G REECE T ECHNICAL R EPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION • 1 SUMMARY ................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Property Description ..................................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Permitting ..................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 History........................................................................................................... 1-3 1.5 Deposit Geology ........................................................................................... 1-4 1.6 Metallurgical Testwork .................................................................................. 1-4 1.7 Mineral Resources ........................................................................................ 1-5 1.8 Mineral Reserves .........................................................................................