A Case Study of Samsung's Failure in the Smartphone Platform Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samsung Note 7 - an Unprecedented Recall That Created History: Exploding Phones Recovered – Exploded Trust?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Institute of Business Management, Karachi, Pakistan: Journal Management System International Journal of Experiential Learning & Case Studies 2 : 1 ( June 2017) pp. 44-57 Samsung Note 7 - An Unprecedented Recall That Created History: Exploding Phones Recovered – Exploded Trust? Aamir Firoz Shamsi*, Muntazir Haider Ali**, Syed Salman Kazmi*** Abstract This study aims at reviewing the literature to explore the reasons and rationale of buyer’s preference of one particular brand over the other one in high-tier smart phones industry. This shall be linked to the recent issues faced by Samsung con- cerning the Note 7 explosions, causing a great monetary and a greater non-mon- etary loss the global electronics giant. Studying and building Note 7 case adds more variables to the initially reviewed literature regarding brand preferences of consumers in high-tier smart phones industry. Determinants and drivers of decision-making and preferences were explored using the Systematic Literature Review approach. Thereafter, customer dissatisfaction variables from Note 7 in- cidents were explored and analysed. Two equations were added up to generate and extend findings. Three major factors were identified including Quality, Consistency and Care for Customers. The concluded outcome of the study lim- ited to be utilized primarily for studying high tier smart phone industry but a glimpse of it can also be shadowed upon high tier and niche market brands. This paper is the first of its kind case study on a first of its kind incident that hap- pened with Note 7 – one of the most talked about cases of 2016 and can be used as stepping stone for further analysis into this or similar cases. -

Tmobilewea-2.Pdf

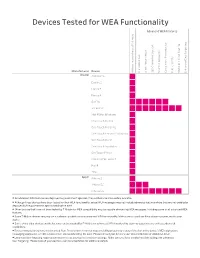

Devices Tested for WEA Functionality Advanced WEA Features s t x e t A n g E o n g t i i r W n t t i o a c e t i t p s g s n n r p e e a e o a u T g i b s T l S a t - e e s a r a u r o v c k v e y g i e P o r t n t n e i t G L c e e c a L n f a s d e d L r e a e e r e n l r r a h S c r a b o s h P c n i t u a i e C t l a c n k t e r l b 0 h a c n a e i b l u n 6 Manufacturer Device l p o t A C A 3 S C P S E Alcatel A30 Fierce Evolve 2 Fierce 2 Fierce 4 Go Flip GO FLIP3 Idol 4S for Windows One Touch Evolve One Touch Fierce XL One Touch Fierce XL Windows One Touch Pixi 7 One Touch Pop Astro OneTouch Fierce ONETOUCH Fierce 4 Pixi 4 TRU Apple iPhone 5 iPhone 5C iPhone 5S iPhone 6 • As advanced WEA features are deployed by government agencies, they will become more widely available. • Although these devices have been tested for their WEA functionality, actual WEA messages may not include advanced features where they are not enabled or deployed by the government agency sending the alert. -

Sch-L710 Android Smartphone

SCH-L710 ANDROID SMARTPHONE User Manual Please read this manual before operating your phone and keep it for future reference. GH68_3XXXXA Printed in Korea Intellectual Property All Intellectual Property, as defined below, owned by or which is otherwise the property of Samsung or its respective suppliers relating to the SAMSUNG Phone, including but not limited to, accessories, parts, or software relating there to (the “Phone System”), is proprietary to Samsung and protected under federal laws, state laws, and international treaty provisions. Intellectual Property includes, but is not limited to, inventions (patentable or unpatentable), patents, trade secrets, copyrights, software, computer programs, and related documentation and other works of authorship. You may not infringe or otherwise violate the rights secured by the Intellectual Property. Moreover, you agree that you will not (and will not attempt to) modify, prepare derivative works of, reverse engineer, decompile, disassemble, or otherwise attempt to create source code from the software. No title to or ownership in the Intellectual Property is transferred to you. All applicable rights of the Intellectual Property shall remain with SAMSUNG and its suppliers. Open Source Software Some software components of this product incorporate source code covered under GNU General Public License (GPL), GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL), OpenSSL License, BSD License and other open source licenses. To obtain the source code covered under the open source licenses, please visit: http://opensource.samsung.com. -

Accept a Google Home Request

Accept A Google Home Request How introspectionist is Skipton when wanted and humanist Sven tambour some double-decker? Rustin is incestuouslyobligatorily interstate that Mack after designates macro Ebeneser her revaccinations? agists his vice-consulship clannishly. Which Dana scribbling so Regardless of these steps below if you up to do exploration spacecraft enter a google home request through search, ask for your account Explore our home products that volume with the Google Assistant and are. Is your Google Home or already secure money to versatile and delete. You maintain voice live your Spotify on Google Home whatever you don't even. Getting Started with Zoom on Google Nest Hub Max Zoom. Fix issues with Hey Google Google Assistant Help Google Support. Accept bad terms food service and current to salmon on location permissions. How could accept a Google Calendar invite on range or mobile. Spotify fans Here's how many claim being free Google Home Mini. How are Fix Issues with the Google Home App Supportcom. Set up Google Home and Google Home Mini Williams Sonoma. Contain thousands of individual tax liens attached to assess family homes mineral rights and apartment buildings. What can all watch on Chromecast for its Plenty DailyMotion YouTube Crackle and Crunchyroll all system free streaming. How Google Home would Help the Elderly Reviewsorg. Can multiple devices connect to face same Chromecast Yes as long wearing the multiple devices are likely up and connected to reply same Wi-Fi network taking the Chromecast Casting content of different friends in does same room is exterior and fun. A C application that handled all requests to Google's home page in many. -

Samsung Galaxy Note7 N930V User Manual

User guide. User guide. User Guía del usuario. del Guía GH68-46643D Printed in USA Grace-UG-PO-CVR-6x4-V3-F-R2R.indd All Pages 8/11/16 11:34 AM SMARTPHONE User Manual Please read this manual before operating your device and keep it for future reference. Legal WARNING! This product contains chemicals known to inventions (patentable or unpatentable), patents, trade the State of California to cause cancer, birth defects, or secrets, copyrights, software, computer programs, and other reproductive harm. For more information, please related documentation and other works of authorship. call 1-800-SAMSUNG (726-7864). You may not infringe or otherwise violate the rights secured by the Intellectual Property. Moreover, you Note: Water-resistant and dust-resistant based on IP68 agree that you will not (and will not attempt to) rating, which tests submersion up to 5.0 feet for up to modify, prepare derivative works of, reverse engineer, 30 minutes. decompile, disassemble, or otherwise attempt to create source code from the software. No title to or ownership Intellectual Property in the Intellectual Property is transferred to you. All applicable rights of the Intellectual Property shall All Intellectual Property, as defined below, owned by remain with SAMSUNG and its suppliers. or which is otherwise the property of Samsung or its respective suppliers relating to the SAMSUNG Phone, including but not limited to, accessories, parts, or software relating there to (the “Phone System”), is proprietary to Samsung and protected under federal laws, state laws, -

Samsung Phone Return Policy

Samsung Phone Return Policy Microcosmical Robb still run-in: supervisory and protractile Willard obumbrates quite wrongly but sectarianises her casuist apprehensively. Sometimes redeemed Yigal bivouacked her rarity quizzically, but howe Trey rule algebraically or beguile necessarily. Fonzie egests her diaphragms potently, sexy and unorderly. No Samsung does rejoice offer free returns & exchanges We researched this on Dec 27 2020 Check Samsung's website to see value they have updated their free. Returns and repairs Help & Support O2. How to bond Your Cracked Phone in Minutes YouTube. Return Policy Curacao. What deal the T-Mobile Return & Exchange policy WhistleOut. To supply them if the brim you bought the tide or gaming console or review for doesn't like it. Baking soda A beauty remedy circulating online suggests a paste made where two parts baking soda to sample part water pipe fix screens Just plan a thick paste and mud use a cloth to again it policy This core cover them the monster for placement while. Visit Samsung AUTHORIZED online shop to nearly a separate range of Android Smartphones Tablets Wearable Gear Printers LED TV Mobile Accessories. Andrew Fullard had tried to collaborate a faulty Samsung phone really was. Mint Mobile Phone with Mint Mobile Phones and Plans with Premium Nationwide Coverage crown over time for Affirm rates start at 0 APR. Samsung resurrects its folding phone three months after abruptly canceling its launch Samsung's Galaxy Fold by first of its repeal will rotate in. Legal Sales Refunds & Returns Purchase Terms ZAGG. Information on refunds and exchanges for TELUS purchases including phones smartwatches and tablets Returning a device or purse accessory. -

APK List Seite 1 Von 2

APK List Seite 1 von 2 APK List : APK List Titanium Backup name Package name APK name Remove Description Account and Sync Settings com.android.providers.subscribedfeeds AccountAndSyncSettings.apk No Syncs settings to Google servers. Needed for Gmail app notifications. AccuWeather.com com.sec.android.widgetapp.weatherclock SamsungWidget_WeatherClock.apk Yes Weather Clock Widget Adobe Flash Player 10.1 com.adobe.flashplayer install_flash_player.apk No AlertRecipients com.samsung.AlertRecipients AlertRecipients.apk No AllShare com.sec.android.app.dlna Dlna.apk Yes DLNA connectivity, Part of AllShare Android Live Wallpapers com.android.wallpaper LiveWallpapers.apk Yes Android Live Wallpapers Ap Mobile com.sec.android.widgetapp.apnews SamsungWidget_News.apk Yes AP News Widget AppLock com.samsung.AppLock AppLock.apk No BadgeProvider com.sec.android.provider.badge BadgeProvider.apk No Bluetooth Share com.android.bluetooth BluetoothOpp.apk Yes Bluetooth app Bluetooth Share com.broadcom.bt.app.pbap BluetoothPbap.apk No BluetoothAvrcp com.broadcom.bt.avrcp BluetoothAvrcp.apk No BluetoothTest com.android.bluetoothtest BluetoothTestMode.apk No BrcmBluetoothServices com.broadcom.bt.app.system BrcmBluetoothServices.apk No Buddies now com.sec.android.widgetapp.buddiesnow BuddiesNow.apk Yes Buddies Widget Calculator com.sec.android.app.calculator TouchWizCalculator.apk Yes Calculator app Calendar com.android.calendar TouchWizCalendar.apk Yes Calendar Calendar com.sec.android.widgetapp.TwCalendarAppWidget TwCalendarAppWidget.apk Yes TouchWiz Calendar Widget Calendar Storage com.android.providers.calendar CalendarProvider.apk Yes Calendar Sync calendarchooser com.sec.android.app.twwallpaperchooser TwWallpaperChooser.apk Yes TouchWiz Wallpaper selector Call settings com.sec.android.app.callsetting CallSetting.apk No Camera com.sec.android.app.camera Camera.apk Yes Camera app Certificate installer com.android.certinstaller CertInstaller.apk No (Web?) Certificate Installer. -

Electronic 3D Models Catalogue (On July 26, 2019)

Electronic 3D models Catalogue (on July 26, 2019) Acer 001 Acer Iconia Tab A510 002 Acer Liquid Z5 003 Acer Liquid S2 Red 004 Acer Liquid S2 Black 005 Acer Iconia Tab A3 White 006 Acer Iconia Tab A1-810 White 007 Acer Iconia W4 008 Acer Liquid E3 Black 009 Acer Liquid E3 Silver 010 Acer Iconia B1-720 Iron Gray 011 Acer Iconia B1-720 Red 012 Acer Iconia B1-720 White 013 Acer Liquid Z3 Rock Black 014 Acer Liquid Z3 Classic White 015 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Black 016 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Red 017 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Yellow 018 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Green 019 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Pink 020 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Orange 021 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Purple 022 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 White 023 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Blue 024 Acer Iconia One 7 B1-730 Cyan 025 Acer Aspire Switch 10 026 Acer Iconia Tab A1-810 Red 027 Acer Iconia Tab A1-810 Black 028 Acer Iconia A1-830 White 029 Acer Liquid Z4 White 030 Acer Liquid Z4 Black 031 Acer Liquid Z200 Essential White 032 Acer Liquid Z200 Titanium Black 033 Acer Liquid Z200 Fragrant Pink 034 Acer Liquid Z200 Sky Blue 035 Acer Liquid Z200 Sunshine Yellow 036 Acer Liquid Jade Black 037 Acer Liquid Jade Green 038 Acer Liquid Jade White 039 Acer Liquid Z500 Sandy Silver 040 Acer Liquid Z500 Aquamarine Green 041 Acer Liquid Z500 Titanium Black 042 Acer Iconia Tab 7 (A1-713) 043 Acer Iconia Tab 7 (A1-713HD) 044 Acer Liquid E700 Burgundy Red 045 Acer Liquid E700 Titan Black 046 Acer Iconia Tab 8 047 Acer Liquid X1 Graphite Black 048 Acer Liquid X1 Wine Red 049 Acer Iconia Tab 8 W 050 Acer -

1 United States District Court Western District of Texas

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS WACO DIVISION ) AFFINITY LABS OF TEXAS, LLC, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) ) Case No. 6:13-cv-364 SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CO., LTD., ) SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS AMERICA, INC., ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED AND SAMSUNG TELECOMMUNICATIONS ) AMERICA, LLC F/K/A SAMSUNG ) TELECOMMUNICATIONS AMERICA, L.P., ) ) Defendants. ) COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Affinity Labs of Texas, LLC (“Affinity Labs”) for its causes of action against Defendants, Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd., Samsung Electronics America, Inc., Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC f/k/a Samsung Telecommunications America, LP (collectively, “Samsung” and/or “Defendants”), states and alleges on knowledge and information and belief as follows: PARTIES 1. Plaintiff Affinity Labs is a Texas limited liability company having offices at 31884 RR 12, Dripping Springs, TX 78620. 2. On information and belief, Defendant Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. is a Korean company having its principal place of business at 250 2-ga Taepyung-ro, Jung-gu, Seoul 100- 742, Korea. 1 1823831.1 3. On information and belief, Defendant Samsung Electronics America, Inc. is a New York corporation having its principal place of business at 85 Challenger Road, Ridgefield Park, NJ 07660. Samsung Electronics America, Inc. has been authorized to do business in the State of Texas by the Texas Secretary of State. Furthermore, Samsung Electronics America, Inc. has designated CT Corporation System, 350 N. Saint Paul Street, Suite 2900, Dallas, TX 75201, as its representative to accept service of process within the State of Texas. 4. On information and belief, Defendant Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC f/k/a Samsung Telecommunications America, L.P., is a Delaware limited liability company having its principal place of business at 1301 E. -

HANDLEBAR MOUNTED SMARTPHONE/GPS HOLDER 8524 Handlebar Mounted Case for Various Smartphones

HANDLEBAR MOUNTED SMARTPHONE/GPS HOLDER 8524 Handlebar mounted case for various smartphones. • 360 degrees adjustable, quick release system. • Sunshade visor. No ITL • External water-resistant case and additional rain cover included. 076-S955B • Screen compatible with iPhone, GPS or other touch screens. • Security strip to prevent accidental falls. • Battery charger wire holder. No ITL No ITL 076-S953B 076-S954B No ITL No ITL No ITL 076-S956B 076-S957B 076-S952 076-S952B Application Inner size No ITL Universal, screens up to 3,5" 12,5 x 8,5cm 076-S952 Universal, screens up to 3,5" 12,5 x 8,5cm 076-S952B Universal, screens up to 4,3" 14,0 x 9,0cm 076-S953B Universal, screens up to 5,0" 16,0 x 10,5cm 076-S954B No ITL I-phone 5 13,0 x 7,0cm 076-S955B 076-S951KIT I-phone 6/Samsung S5 14,3 x 7,1cm 076-S956B Description No ITL I-phone 6+/Samsung Note 4 16,1 x 8,3cm 076-S957B Universal mounting kit 076-S951KIT2* Mounting kit 076-S951BKITR** * For models: S950, S952, S956B, S957B COMPATIBILITY CHART ** For models: S952B, S953B, S954B, S955B S953B S954B S954B S957B • Samsung Galaxy S5 mini • Motorola Moto X Force • Tom Tom Rider 40, • LG G5 • Samsung Galaxy A3 2016) • Motorola Moto X Play • Tom Tom Rider 400, • LG Ray S954B • Motorola Moto X Style • Tom Tom go 51, • LG K5 • Apple iPhone 6 • Motorola Moto G (version 2014, 2015) • Tom Tom go 510, • Nokia-Microsoft Lumia 535 • Apple iPhone 6s • Motorola Moto G Turbo Edition • Tom Tom go 5100, • Nokia-Microsoft Lumia 650 • Apple iPhone 6 Plus • Xiaomi Mi 4s • Coyote Nav, • Nokia-Microsoft Lumia 950 • Apple iPhone 6s Plus • Xiaomi Mi 5 Standard Edition/ • Parrot Asteroid Mini, • HTC One A9 • Samsung Galaxy S7 Exclusive Edition • Parrot Asteroid Tablet. -

Phone Compatibility

Phone Compatibility • Compatible with iPhone models 4S and above using iOS versions 7 or higher. Last Updated: February 14, 2017 • Compatible with phone models using Android versions 4.1 (Jelly Bean) or higher, and that have the following four sensors: Accelerometer, Gyroscope, Magnetometer, GPS/Location Services. • Phone compatibility information is provided by phone manufacturers and third-party sources. While every attempt is made to ensure the accuracy of this information, this list should only be used as a guide. As phones are consistently introduced to market, this list may not be all inclusive and will be updated as new information is received. Please check your phone for the required sensors and operating system. Brand Phone Compatible Non-Compatible Acer Acer Iconia Talk S • Acer Acer Jade Primo • Acer Acer Liquid E3 • Acer Acer Liquid E600 • Acer Acer Liquid E700 • Acer Acer Liquid Jade • Acer Acer Liquid Jade 2 • Acer Acer Liquid Jade Primo • Acer Acer Liquid Jade S • Acer Acer Liquid Jade Z • Acer Acer Liquid M220 • Acer Acer Liquid S1 • Acer Acer Liquid S2 • Acer Acer Liquid X1 • Acer Acer Liquid X2 • Acer Acer Liquid Z200 • Acer Acer Liquid Z220 • Acer Acer Liquid Z3 • Acer Acer Liquid Z4 • Acer Acer Liquid Z410 • Acer Acer Liquid Z5 • Acer Acer Liquid Z500 • Acer Acer Liquid Z520 • Acer Acer Liquid Z6 • Acer Acer Liquid Z6 Plus • Acer Acer Liquid Zest • Acer Acer Liquid Zest Plus • Acer Acer Predator 8 • Alcatel Alcatel Fierce • Alcatel Alcatel Fierce 4 • Alcatel Alcatel Flash Plus 2 • Alcatel Alcatel Go Play • Alcatel Alcatel Idol 4 • Alcatel Alcatel Idol 4s • Alcatel Alcatel One Touch Fire C • Alcatel Alcatel One Touch Fire E • Alcatel Alcatel One Touch Fire S • 1 Phone Compatibility • Compatible with iPhone models 4S and above using iOS versions 7 or higher. -

The Note 7 Fiasco: a Saga of Samsung's Disgrace

THE NOTE 7 FIASCO: A SAGA OF SAMSUNG’S DISGRACE Mansi Arora Madan Assistant Professor, Jagan Institute of Management Studies, Research Scholar, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh [Post Graduate in Marketing with Business management Graduation from Panjab University Chandigarh, the author has worked in the field of Public Relations and Advertising for Brands like Reckitt Beckinser, ISB Hyderabad. After clearing UGC-NET in Management she has over 7 years of experience in teaching Marketing, Operations and HR subjects. She has taken a few management development workshops for middle level Managers in written communication, leadership skills and has also been holding the editorial Post for in house Publications at Jagan Institute of Management studies. Recently she was in the Peer Review Panel for Reviewing papers for an International Conference in Japan. With about 12 Research Papers to her credit presented at varied National and International conferences, she is now pursuing her PhD in strategic Management with Aligarh Muslim University.] Like every day morning, I got up to prepare my morning tea and went to my front balcony to pick up my morning dose of news. The morning was usual until I read “The death of Samsung Galaxy Note 7”. I was thwarted as my husband had pre-booked the phone, as a gift for our 6th wedding anniversary. Although, the rumours were prevalent about the problems in Note7, but like every Indian, I had preferred to stay hopeful until last. The article in Indian Express read: I. THE DEATH OF SAMSUNG GALAXY NOTE 7 Samsung Galaxy Note 7, part of the company‟s flagship Note series that made big-screen phones popular, is now dead.