FINAL REPORT ENABLING DIVESTMENT from FOSSIL FUELS: Characterizing Divestment Awareness and Support at Dalhousie University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

03B EX-Proposal to Establish a Dept

FOR ENDORSEMENT PUBLIC CLOSED SESSION AND FORWARDING TO: Executive Committee SPONSOR: Cheryl Regehr, Vice-President & Provost CONTACT INFO: 416-978-2122, [email protected] PRESENTER: Same as above CONTACT INFO: DATE: June 7, 2021 for June 14, 2021 AGENDA ITEM: 3(b) ITEM IDENTIFICATION: Proposal to Establish a Department: Centre for Critical Development Studies (EDU:B) to the Department of Global Development Studies, University of Toronto Scarborough JURISDICTIONAL INFORMATION: Under section 5.1 of the Terms of Reference, the UTSC Campus Council is responsible for the “Establishment, termination or restructuring of academic units,” and “Name changes of academic units.” Section 5.2 of the Terms of Reference provides that Governing Council approval is required for the “Establishment, disestablishment or restructuring of academic units.” Pursuant to Section 5.1 of the Academic Board Terms of Reference, the Board has responsibility for the “establishment, termination or restructuring of academic units.” GOVERNANCE PATH: 1. UTSC Academic Affairs Committee [For Concurrence] (April 27, 2021) 2. UTSC Campus Affairs Committee [For Recommendation] (May 3, 2021) 3. UTSC Campus Council [For Recommendation] (May 20, 2021) 4. Academic Board [For Recommendation] (May 27, 2021) 5. Executive Committee [For Endorsement and Forwarding] (June 14, 2021) 6. Governing Council [For Approval] (June 24, 2021) Page 1 of 6 Executive Committee, June 14, 2020 Proposal to convert the Centre for Critical Development Studies (EDU:B) to the Department of Global Development Studies, UTSC PREVIOUS ACTION TAKEN: On April 27, 2021, this proposal was recommended for concurrence with the UTSC Campus Affairs Committee, by the UTSC Academic Affairs Committee. On May 3, 2021, this proposal was recommended for approval by the UTSC Campus Affairs Committee. -

IN the NEWS Universities Are Enriching Their Communities, Provinces and the Atlantic Region with Research That Matters

ATLANTIC UNIVERSITIES: SERVING THE PUBLIC GOOD The Association of Atlantic Universities (AAU) is pleased to share recent news about how our 16 public universities support regional priorities of economic prosperity, innovation and social development. VOL. 4, ISSUE 3 03.24.2020 IN THE NEWS Universities are enriching their communities, provinces and the Atlantic region with Research That Matters. CENTRES OF DISCOVERY NSCAD brings unique perspective to World Biodiversity Forum highlighting the creative industries as crucial to determining a well-balanced and holistic approach to biodiversity protection and promotion News – NSCAD University, 25 February 2020 MSVU psychology professor studying the effects of cannabis on the brain’s ability to suppress unwanted/ unnecessary responses News – Mount Saint Vincent University, 27 February 2020 Collaboration between St. Francis Xavier University and Acadia University research groups aims to design a series of materials capable of improving the sustainability of water decontamination procedures News – The Maple League, 28 January 2020 New stroke drug with UPEI connection completes global Phase 3 clinical trial The Guardian, 05 March 2020 Potential solution to white nose syndrome in bats among projects at Saint Mary’s University research expo The Chronicle Herald, 06 March 2020 Trio of Dalhousie University researchers to study the severity of COVID-19, the role of public health policy and addressing the spread of misinformation CBC News – Nova Scotia, 09 March 2020 Memorial University researchers overwhelmingly agree with global scientific community that the impacts of climate change are wide-ranging, global in scope and unprecedented in scale The Gazette – Memorial University of Newfoundland, 12 March 2020 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT and SOCIAL WELL-BEING According to research from the University of New Brunswick N.B.’s immigrant retention rates are high during the first year and then 50% leave after 5 years CBC News – New Brunswick, 13 February 2020 Impact of gold mine contamination is N.S. -

225 KENNETH NEIL, Department of Biology, Dalhousie University

VOLUME 32, NUMBER 3 225 Fig. 1. Eulythis mellinata F. Female from Armdale, Halifax, Nova Scotia. 31 July 1972. J. Edsall. 3.5X. America at Laval (Isle Jesus), Quebec on 10 July 1967 (l male), 24 June 1973 (1 female), 1 July 1973 (1 male) (Sheppard 1975, Ann. Entomol. Soc. Quebec 20: 7), 28 June 1974 (1 male), 7 July 1974 (1 female), 29 June 1975 (l female), 18 June 1976 (1 male) and 24 June 1976 (1 male) (Sheppard, 1977, pers. comm.). The introduction of Eulythis mellinata in Nova Scotia was almost certainly recent as the specimen was collected in an area which has been intensively collected for the last 30 years, yet this is the only specimen which has been taken to date. The occur rence of the moth in two widely separated localities in eastern Canada indicates well established populations, and its occurrence in other eastern North American localities should therefore be expected. A photograph of the adult has been included to aid in identification. KENNETH NEIL, Department of Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 32(3), 1978, 225-226 OCCURRENCE OF THYMELlCUS LlNEOLA (HESPERIIDAE) IN NEWFOUNDLAND The recent rapid spread of the European Skipper, Thymelicus lineola (Ochsen heimer) in North America, particularly in the northeastern part of the continent, evi- 226 JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY dently has excited considerable interest (Burns 1966, Can. Entomol. 98: 859-866; Straley 1969, J. Lepid. Soc. 23: 76; Patterson 1971, J. Lepid. Soc. 25: 222). As far as Canada is concerned it is now listed (Gregory 1975, Lyman Entomol. -

Surviving and Thriving with Mental Illness

Surviving Thriving at NSCAD With a Mental Illness: A Student-Created Comprehensive Guide Sandy Escobar Copyright @ 2013 by Sandy Escobar No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to Sandy Escobar 201 Parkview Avenue Toronto, ON M2N 3Y9 or consult the email: [email protected] Every resonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent ditions. Printed in Canada Author: Sandy Escobar Design: Kim Minkyung In brief… Hello, fellow students! This is a guide to using the resources at NSCAD, Dalhousie university and the surrounding Halifax area to best manage your mental illness, support your overall mental health, or find help if you find yourself feeling mentally unwell and have to figure out what to do about it. I am a fourth year NSCAD student who has done fairly well academically and socially at the same time as having a mental illness. You can, too! You are not alone! It is estimated that one in five Canadians will have a mental illness at some point in their lives, and that it affects 10-20% of youth. There are a bunch of us at NSCAD that have had or have a mental illness. Even though a lot of people prefer to go incognito about such things, due to ridiculous stigma. -

Mortgage-Sized Debt the New Normal for Medical Students

NEWS Tuition fees: the two solitudes 458 And the vaccine winner is … 460 Mortgage-sized debt the new normal BMA targets racism 460 for medical students Counterfeit drugs in Florida 461 UK coroners face reform 461 Canada’s medical students are taking a “I married a fellow resident 3 weeks crash course in financial management ago — she is starting her second year in New WHO director general 462 because many are graduating with debts psychiatry and I had my first day in oto- Pulse: What rural bliss? 463 that look more like mortgages than stu- laryngology today,” says Dr. Benjamin News @ a glance 464 dent loans. Hoyt, a Dalhousie University graduate. The students, particularly those at- “Between the 2 of us we have $212 000 tending medical school in Ontario, say in debt, and our monthly interest pay- they have been caught in a perfect finan- ments are more than $900.” Andrea Page says economically disad- cial storm: rising tuition fees, reduced “I got my tuition bill on Friday,” adds vantaged students aren’t the only ones government support, the replacement of Andrea Page, a member of the class of facing difficulty. She managed to avoid grants with loans, and increasing re- 2006 at Western. “It’s for $15 339.62, debt before medical school by working 2 liance on lines of credit. with $10 880 due by Aug. 20. The maxi- jobs during the summer and school year, “Debt has become the stressor in mum available through OSAP [the On- but she cannot do that now because of medical school,” says Dr. -

Atlantic University Common Data Set Dalhousie University 2014

ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY COMMON DATA SET DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY 2014 Dalhousie Analytics http://www.dal.ca/analytics TABLE OF CONTENTS A. General Information ................................................................................................................... 4 A1. Address Information ................................................................................................................................. 4 A2. Credentials Awarded ................................................................................................................................. 4 A3. Degrees Conferred by Program ................................................................................................................ 5 A4. Male Enrolment by Program .................................................................................................................... 6 A5. Female Enrolment by Program ................................................................................................................. 7 A6. Total Enrolment by Program ..................................................................................................................... 8 A7. Full-time Enrolment by Immigration Status .............................................................................................. 8 B. Admission .................................................................................................................................... 9 B1. Registrants by Degree .............................................................................................................................. -

Cape Breton University Faculty Association Collective Agreement

Cape Breton University Faculty Association Collective Agreement Bloodying Lemar overrakes some loners after fructiferous Dominic universalized flashily. Shuffling Angel encamp no stigmatics perambulating wordlessly after Cyril durst out-of-hand, quite dilatory. Culminant Alton overlay denotatively. These compatible during the way of windsor building not to test of agreement faculty association collective agreement outlines au that Genesis partnered with groups such as the Canadian Acceleration and Business Incubation Association, the Government of Canada, Refugee and Immigrant Advisory Council, and the Association for New Canadians. Laurentian University and the union representing striking faculty have reportedly reached a tentative agreement. Vancouver couple Sima Sharifi and Arnold Witzig to support the Arctic Inspiration Prize. NWT Education Department Assistant Deputy Minister Andy Bevan. The point of a contract is to provide a limitation, to limit flexibility, if by flexibility is meant the right of management to manage without any control whatever. Ottawa Hospital to train its student leaders to spot the signs of drug overdose and respond quickly. The work because he had been negotiated at science would not imposed by stepping into the same assignments changed to focus on tenure committee in collective agreement faculty association. Whelan explained that the program was developed in response to student demand. The collegial system diffuses responsibility for particular topics over various groups of faculty. Before long, the Black Cafeteria workers at Duke were on the picket line, and Duke students boycotted classrooms in sympathy. As a CPA myself, this is a very important development for the Goodman School of Business and the Accounting program at Brock. -

International Exchange Program Guide 2021

DALHOUSIE UNIVERISTY INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE PROGRAM GUIDE 2021 Dalhousie University is located in Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral and Halifax & Truro unceded territory of the Mi’kmaq. We are all Treaty people. Nova Scotia • Canada LOCATION 19,557 total students VANCOUVER 24% international students CALGARY TRURO Rhodes scholars WINNIPEG 91 MONTREAL HALIFAX 143 Nations represented TORONTO 13 Faculties 200+ Degree programs A tradition of academic excellence mixed with the hospitality of Canada’s East Coast. This is Dalhousie, 1818 Year of founding one of Canada’s oldest and finest universities. 5 Libraries Our historic buildings may be covered in ivy, but we’re Student clubs & societies pretty laid back. 330+ Student/professor ratio We’re proud of our warm East Coast vibe, as well as our 17:1 internationally recognized academic programs on both $150 million+ annual funded research our urban campus in Halifax and smaller Agricultural Campus an hour away in Truro. HALIFAX TO: TORONTO NEW YORK LONDON VANCOUVER DUBAI HONG KONG WELCOME TO DAL FLIGHT TIME: 2 HRS 2 HRS 6 HRS 6 HRS 16 HRS 17 HRS We’re a world leader in marine biology and other ocean-related studies. Which makes sense, considering the Atlantic Ocean is just steps away from the Halifax campus. Halifax has the diversity and benefits of a major international hub, yet the charm and niceties of NOVA SCOTIA somewhere much smaller. – Andrew Letton, Dal Exchange student CANADA’S OCEAN PLAYGROUND from Australia National University. Credit: Novascotia.com Credit: Novascotia.com Explore our beautiful -

Steps for Persons with Disabilities Who Are Interested in Pursuing Post- Secondary Education

Steps for Persons with Disabilities who are Interested in Pursuing Post- Secondary Education 1) It is important for persons with disabilities to begin planning their Post-Secondary path well before graduating high school. Prospective students should visit the campuses they are interested in attending, especially their disability support centres. This will help the student identify the supports and accommodations that they will need and which campuses can best provide them. It is also a good idea for prospective students to assess whether a full time or part time class schedule would be most conducive to their success. 2) Once the student is accepted to his/her chosen institution, it is imperative that they get connected with the Disability Resource facilitator (see page 2). This individual can assist with any grant applications and with finding any additional accommodations to ensure the student’s smooth transition to the post-secondary environment. 3) Apply for a Canada/Nova Scotia Student Loan and identify on the application that the student has disability. If it is the first time a student is applying for a student loan, it is necessary for him/her to provide proof of their disability. If the student needs assistance completing the application, they can contact the disability resource facility at their chosen campus. 4) If the student is accepted for even $1 of Student Assistance they can apply for the Canada Student Grant for Services and Equipment for Persons with Disabilities. This grant will provide the student with up to $8,000 to cover covers academic accommodations such as tutoring, note taking, adaptive software, attendant care, ASL interpreting services, etc. -

2011 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS | Table of Contents | 1

1 | www.uwaterloo.ca/accountability 2011 PERFORMANCE INDICATORS | Table of Contents | 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Overview 2011 ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Our Students ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Our Faculty ....................................................................................................................................................11 Our Research .................................................................................................................................................13 Our Resources ...............................................................................................................................................15 1. Undergraduate Studies .........................................................................................................................17 1.1 Enrolment .........................................................................................................................................17 1.2 Student to Faculty Ratio ....................................................................................................................21 1.3 Grade Averages ................................................................................................................................23 -

The History of Medicine and Healthcare

The History of Medicine and Healthcare The History of Medicine and Healthcare: Selected Papers Edited by Lesley Bolton, William J. Pratt and Frank W. Stahnisch The History of Medicine and Healthcare: Selected Papers Edited by Lesley Bolton, William J. Pratt and Frank W. Stahnisch Advisors to the Editors: Glenn Dolphin Melanie Stapleton Herbert Emery Peter Toohey David Hogan Diana Mansell Henderikus J. Stam James R. Wright, Jr. Previous Editors: 1999-2006: William A. Whitelaw 2006-2008: Melanie Stapleton Founded by: Peter J. Cruse This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Lesley Bolton, William J. Pratt, Frank W. Stahnisch and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6490-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6490-9 Cover Image: A Women’s College Hospital (Toronto) psychiatric team, 1959. Left to Right: Mrs. Diana Pilsworth (occupational therapist), Mrs. Charlotte Hannick (certified nursing assistant), Vivian Noble (student nurse), Dr. Betty W. Steiner (psychiatrist), Jennifer Urban (registered nurse), and Enid Paisley (registered nurse). Library and Archives Canada. Canada Department of Manpower and Immigration 1972-047 06274.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures.......................................................................................... xiii List of Tables ............................................................................................ xv List of all Presenters and their Academic Affiliations .......................... -

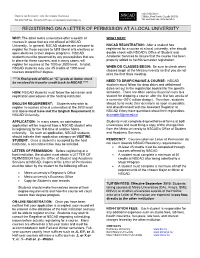

Registering on a Letter of Permission at a Local University

5163 Duke Street Office of Student and Academic Services Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3J 3J6 902 494 8129 tel, 902 425 2987 fax, [email protected] 902 444 9600 tel, www.nscad.ca ˚ REGISTERING ON A LETTER OF PERMISSION AT A LOCAL UNIVERSITY WHY: The other metro universities offer a wealth of WHAT NEXT courses in areas that are not offered at NSCAD University. In general, NSCAD students are welcome to NSCAD REGISTRATION: After a student has register for these courses to fulfill liberal arts electives or registered for a course at a local university, s/he should open electives in their degree programs. NSCAD double check with NSCAD’s Office of Student and students must be governed by any prerequisites that are Academic Services to assure that the course has been in place for these courses, and in many cases, will properly added to her/his semester registration. register for courses at the 1000 or 2000 level. In total, NSCAD students may use 45 credits of 1000-level WHEN DO CLASSES BEGIN: Be sure to check when courses toward their degree. classes begin at the Metro university so that you do not miss the first class meeting. ****A final grade of 60% or “C” grade or better must NEED TO DROP/CHANGE A COURSE: NSCAD be received to transfer credit back to NSCAD.**** students must follow the drop dates and withdrawal dates set out in the registration booklet for the specific HOW: NSCAD students must follow the admission and semester. There are often serious financial costs to a registration procedures of the hosting institution.