Developing Effective Culturally-Specific Sexual Misconduct Policies and Prevention Strategies for Campuses in Micronesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bus Schedule Carmel Catholic School Agat and Santa Rita Area to Mount Bus No.: B-39 Driver: Salas, Vincent R

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2020 - 2021 Dispatcher Bus Operations - 646-3122 | Superintendent Franklin F. Tait ano - 646-3208 | Assistant Superintendent Daniel B. Quintanilla - 647-5025 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRES ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. THERE WILL BE ONE CHILD PER SEAT FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING. PLEASE ANTICIPATE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTERS. THANK YOU. TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO O/C-30 Hanks 5:46 2:29 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL O/C-29 Oceanview Drive 5:44 2:30 A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 O/C-28 Nimitz Hill Annex 5:40 2:33 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:15 1:50 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) BUS NO.: B-123 A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP DROP OFF A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 SCHOOL A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:50 3:30 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 HARRY S. -

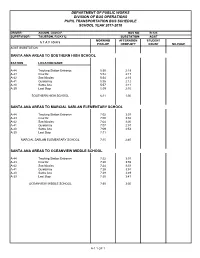

Department of Public Works Division of Bus Operations Pupil Transportation Bus Schedule School Year 2017-2018

DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: AGUON, DAVID F. BUS NO. B-123 SUPERVISOR: TAIJERON, RICKY U. SUBSTATION: AGAT MORNING AFTERNOON STUDENT S T A T I O N S PICK-UP DROP-OFF COUNT MILEAGE AGAT SUBSTATION SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL STATION LOCATION NAME A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 A-39 Last Stop 5:59 2:10 SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL 6:11 1:50 SANTA ANA AREAS TO MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:02 3:03 A-43 Cruz #2 7:00 3:02 A-42 San Nicolas 7:04 3:00 A-41 Quidachay 7:07 2:57 A-40 Santa Ana 7:09 2:53 A-39 Last Stop 7:11 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:15 2:40 SANTA ANA AREAS TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 7:22 3:57 A-43 Cruz #2 7:20 3:55 A-42 San Nicolas 7:24 3:53 A-41 Quidachay 7:26 3:51 A-40 Santa Ana 7:28 3:49 A-39 Last Stop 7:30 3:47 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:30 A-1 1 OF 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS DIVISION OF BUS OPERATIONS PUPIL TRANSPORTATION BUS SCHEDULE SCHOOL YEAR 2017-2018 DRIVER: BORJA, GARY P. -

Gdoe School Nurses Support and Impact

10/29/2020 Guam Legislature Mail - M&C Fwd: GDOE SY19-20 Annual State of Public Education Report (ASPER) Guam Legislature Clerks <[email protected]> M&C Fwd: GDOE SY19-20 Annual State of Public Education Report (ASPER) 1 message Speaker's Office <[email protected]> Wed, Oct 28, 2020 at 5:23 PM To: Clerks Office <[email protected]> Cc: Rennae Meno <[email protected]> 10/28/20 5:08 PM 10/28/20 SY 2019-2020 Annual State of Public Education Report.* Department of Education-Office of the Superintendent 35GL-20-2365 Sinseru yan Minagåhet, Office of the Speaker ● Tina Rose Muña Barnes Committee on Public Accountability, Human Resources & the Guam Buildup 35th Guam Legislature I Mina’trentai Singko na Liheslaturan Guåhan Guam Congress Building | 163 Chalan Santo Papa | Hagatna, GU 96910 T: (671) 477-2520/1 [email protected] This e-mail message is intended only for the use of the individual or entity named above and may contain confidential and privileged information. If you are not the intended recipient, any disclosure, copying, distribution or use of the information contained in this transmission is strictly PROHIBITED. If you have received this transmission in error, please immediately notify us by replying to [email protected] and delete the message immediately. Thank you very much. Gumai pribilehu yan konfedensia este siha na mensåhi. Solo espesiåtmente para hågu ma entensioña pat ma aturisa para unrisibi. Sen prubidu kumu ti un ma aturisa para manribisa, na’setbe, pat mandespåtcha. Yanggen lachi rinisibu-mu nu este na mensåhi , put fabot ago’ guatu gi I numa’huyong gi as [email protected] yan despues destrosa todu siha I kopian mensåhi. -

36Gl-21-0269.*

COMMITTEE ON RULES RECEIVED: March 8, 2021 4:27 P.M. Doc. No. 36GL-21-0269.* March 8, 2021 MEMORANDUM To: Honorable Therese M. Terlaje Speaker, 36th Guam Legislature From: Superintendent of Education Subject: Compliance with 4GCA §4117 (d). Temporary Assignments Buenas yan Hafa Adai! Transmitted herewith are all Temporary Assignments for the Guam Department of Education effective 03/01/2021 to current. Should your office have any questions or need additional information, please feel free to contact Leilani Marie F. Keone, Personnel Services Administrator, at 475-0496 or via email at [email protected]. Senserameñte, JON J.P. FERNANDEZ Attachments cc: Personnel Services Administrator Doc. No. 36GL-21-0269.* DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT www.gdoe.net 501 Mariner Avenue Barrigada, Guam 96913 Telephone: (671)300-1547/1536Fax: (671)472-5001 Email: [email protected] JON J. P. FERNANDEZ Superintendent of Education PERSONNEL MATTERS DATE: March 01, 2021 No. _____________21-013 SUBJECT: Temporary Assignment - Carla Masnayon INQUIRIES: Office of the Superintendent of Education Effective March 01, 2021 through April 19, 2021, Carla Masnayon, Principal, Simon Sanchez High School will assume the duties and responsibilities as the Acting Principal of D.L. Perez Elementary School in the absence of Rebecca Duenas, Principal. This assignment is in addition to her duties and responsibilities as the Principal of Simon Sanchez High School. Your continued support in extending your cooperation is appreciated. _________________________________________________ _________3/8/2021 ________ JON J.P. FERNANDEZ DATE Superintendent of Education cc: Deputy Superintendents Administrator, Personnel Services Division All Division Heads All School Administrators Doc. No. 36GL-21-0269.* DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT www.gdoe.net 501 Mariner Avenue Barrigada, Guam 96913 Telephone: (671)300-1547/1536Fax: (671)472-5001 Email: [email protected] JON J. -

Government of Guam Tiyan Campus Tax Credits Program

Government of Guam Tiyan Campus Tax Credits Program Performance Audit October 1, 2008 through September 30, 2014 OPA Report No. 14-07 December 2014 Government of Guam Tiyan Campus Tax Credits Program Performance Audit October 2008 through September 2014 OPA Report No. 14-07 December 2014 Distribution: Governor of Guam Lt. Governor of Guam Speaker, 32nd Guam Legislature Senators, 32nd Guam Legislature Superintendent, Guam Department of Education Administrator, Guam Economic Development Authority Director, Department of Revenue and Taxation Director, Department of Administration Director, Bureau of Budget and Management Research Guam Media via E-Mail Table of Contents Page Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 Results of Audit ............................................................................................................................. 6 Tiyan High and GDOE Central Office to Cost $260.3M ........................................................... 7 Five Schools to Cost $406.1M .................................................................................................... 7 Cost Comparisons ....................................................................................................................... 9 $36.2M in Lease Payments and Collateral Equipment over 65 Months -

JIC Release No. 755 August 18, 2021, 7:10 P.M

Joint Information Center - JIC Release No. 755 August 18, 2021, 7:10 p.m. (ChST) Thirty-seven of 560 Test Positive for COVID-19; Five GDOE Students Test Positive for COVID-19; Physicians Advisory Issued for Additional Dose of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine; COVID-19 Vaccination and Testing Schedule; Issuance of SNAP P-EBT Cards Continue Results: 37 New Cases of COVID-19 Thirty-seven (37) new cases of COVID-19 were identified out of 560 tests performed on August 17. Thirteen (13) cases were identified through contact tracing. To date, there have been a total of 9,118 officially reported cases of COVID-19 with 144 deaths, 412 cases in active isolation – inclusive of sixteen (16) hospitalized cases with five (5) hospitalized cases receiving ICU-level care, and 8,562 not in active isolation. The CAR Score is 9.2. Guam COVID-19 vaccination update: As of August 17, a total of 106,108 (77.85%) of Guam’s eligible population (residents 12 years and older) have received either both doses in the two-dose series (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna) or the single-dose series (Johnson & Johnson/Janssen) of the COVID-19 vaccine. This percentage includes 8,444 fully vaccinated residents between the ages of 12 – 17, as well as Guam's fully vaccinated adult population of 97,664. Five GDOE Students Test Positive for COVID-19 Today, the Guam Department of Education (GDOE) confirmed five separate cases of COVID-19 involving students at Adacao Elementary School, Machananao Elementary School, Agueda I. Johnston Middle School, George Washington High School and Okkodo High School. -

Students First, Mission Always

STUDENTS FIRST, MISSION ALWAYS About GCC 1 Programs 2 GCC OFFERS Finances 3 • 22 associate degrees / 18 certificate programs Outlook 4 • Adult Education (including high school equivalency testing) • Apprenticeship (on-the-job training where you work) • Continuing Education & Workforce Development 11 Career & Technical Education (CTE) programs in Guam public high schools • Courses at several Mayors’ offices Guam Public Law 14-77, which established Guam Community College, also designated GCC to serve as the State Board of Control for Vocational Education, administering federal CTE grants for training and workforce development. NEW LOOK! GCC launched its new logo system on Feb. 16, 2017, to celebrate its 40th anniversary. Now each program has ACCREDITATION its own variation of our main logo – a new, fresher, more sustainable look for the College! GCC is accredited by the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, Western Association 40TH COMMENCEMENT of Schools and Colleges. On May 12, 2017, GCC conferred a record 573* degrees, certificates, and/or diplomas upon 525 graduates at the University of Guam Calvo Field House. For the second consecutive year, it was the largest graduating class and the largest number of credentials GOVERNANCE conferred in the College’s 40-year history. President: Mary A. Y. Okada, Ed.D. *Some graduates earned more than one credential. VP Academic Affairs: R. Ray Somera, Ph.D. VP Finance & Administration: OUR MISSION Carmen K. Santos, CPA Guam Community College is a leader Board of Trustees: in career and technical workforce Frank P. Arriola, Chair development, providing the highest quality, student-centered education Foundation Board of Governors: FISCAL YEAR 2017 and job training for Micronesia. -

AY2016-2017 Degrees Conferred** Number of Degrees Conferred in 1 Academic Year 2016‐2017 Bachelors 433 Masters 79% 118 551 Degrees Conferred 21%

A Message from the President I am pleased to announce the 2016‐2017 edition of the University of Guam (UOG) Fact Book. The Fact Book is designed as a convenient and authoritative reference guide and as a historical record of our growing University. The book includes data and information on our faculty, students, administration, physical resources and revenue sources. For the 2016‐2017 academic year, there have been many notable accomplishments by UOG, to include: Student enrollment for Fall Semester 2016 was 3875 which is an 18% increase over student enrollment in Fall 2006, and represents on average a 2% increase per year over the past 10 years; 551 degrees were conferred, expansion of our athletic programs; the Good to Great initiative continued to be implemented helping UOG in realizing its potential; University‐generated revenues were $54.2 million of the total revenues and contributions of $89.3 million. Since our beginning in 1952 as a teacher training junior college in Mongmong, the University of Guam has grown into the largest U.S. accredited institution of higher learning on this side of the international dateline and has graduated over 17,200 students who are now engaged, dynamic professionals in Guam, our neighboring island communities and across the world. Today, the University offers 26 undergraduate degrees and 14 graduate programs. We hope that the information presented here will highlight the many facets that comprise the University of Guam and will help you gain a greater understanding of the nature of the University. Biba UOG! Dr. Robert A. Underwood President -i- A Message from the Senior Vice President Academic and Student Affairs Hafa Adai! I am pleased to present the tenth edition of the University of Guam Fact Book. -

Log on to to View the Schedule Online

BUS SchoolSCHEDULE Year 2021 - 2022 THE DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS, BUS OPERATIONS REQUIRE ALL STUDENTS TO WEAR A FACE MASK PRIOR TO BOARDING THE BUS. Designed and printed by THERE MAY BE DELAYS IN PICK UP AND DROP OFF AT DESIGNATED BUS SHELTER, THANK YOU. IF YOUR CHILD IS SICK, PLEASE HAVE THEM STAY HOME. DISPATCHER BUS OPERATIONS - 646-3122 TENJO VISTA AND SANTA RITA AREAS TO PAGACHAO AREA TO MARCIAL SABLAN OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL (A.M. ONLY) A-2 Tenjo Vista Entrance 7:30 4:01 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:00 A-3 Tenjo Vista Lower 7:31 4:00 MARCIAL SABLAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL 7:10 AGAT A-5 Perez #1 7:35 3:56 PAGACHAO AREA TO OCEANVIEW MIDDLE A-14 Lizama Station 7:37 3:54 SCHOOL SANTA ANA AREAS TO SOUTHERN HIGH SCHOOL A-15 Borja Station 7:38 3:53 A-46 Round Table 7:15 3:45 STATION LOCATION NAME PICK UP A-16 Naval Magazine 7:39 3:52 A-38 Pagachao Upper 7:22 3:53 A-44 Tracking Station Entrance 5:50 2:19 A-17 Sgt. Cruz 7:40 3:51 A-37 Pagachao Lower 7:25 3:50 A-43 Cruz #2 5:52 2:17 A-18 M & R Store 7:41 3:50 OCEANVIEW MIDDLE SCHOOL 7:35 3:25 A-42 San Nicolas 5:54 2:15 A-19 Annex 7:42 3:49 A-41 Quidachay 5:56 2:12 A-20 Rapolla Station 7:43 3:48 HARRY S. TRUMAN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL TO A-40 Santa Ana 5:57 2:11 SANTA RITA AREA (P.M. -

0-2016-CAFR-FINAL-V3.5-Signed.Pdf

Front Cover: Famed Guam Photographer and 1989 Pulitzer Prize recipient for Feature Photography Manny Crisostomo captured the Guam-hosted 2016 Festival of Pacific Arts Fashion model, Ms. Siguenza, as she proudly flaunts a Guam-themed fashion attire during the Fashion show. COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT For The Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2016 Edward J. B. Calvo Governor of Guam Christine W. Baleto Director of Administration Kathrine B. Kakigi, CPA Financial Manager Prepared By: The Division of Accounts P.O. Box 884 Hagatna, Guam 96932 Location: 7th Floor, ITC Building, Suite 707 590 South Marine Corps Drive, Tamuning (671) 475-1260/1169 ;. ,., ,. ... " ' Introductory Cover: Frontal view of Ms. Siguenza modeling the pre-occupational Guam attire as Famed Guam Photographer and 1989 Pulitzer Prize recipient for Feature Photography, during the Guam-hosted 2016 Festival of the Pacific Arts Fashion show. The event was the largest gathering of Pacific Islanders, including the Oceania area (New Zealand and Australia). 2016 Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY SECTION Letter of Transmittal .................................................................................................................................................................................... i Organizational Chart ................................................................................................................................................................................ xii Elected Officials ........................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Guam Department of Education

Guam Department of Education Citizen’s Centric Report Guam Department of Education Goals Goal # 1 All students will graduate from high school prepared to pursue post-secondary education on or off-island or to assume gainful employment with the private or public sector August 2016 Goal # 2 All students will successfully progress from grade to grade and from one level of schooling to FY 2015 another in order to maximize opportunities to successfully graduate from high school SY 2014-2015 Goal # 3 All Guam Department of Education personnel will meet high standards for qualifications and SY 2015-2016 on-going professional development and will be held accountable for all assigned responsibilities In this issue Goal # 4 All members of the Guam Department of Education Community will establish and sustain a safe, positive and supportive environment ABOUT GDOE 1 Goal # 5 All Guam Department of Education’s operations activities will maximize the critical uses of PERFORMANCE 2 limited resources and meet high standards of accountability About Us GDOE is a single unified school # of Students in % Students in FINANCES 3 Disability Categories district consisting of Kindergarten thru 12 grade. the Category the Category Our 26 Elementary Schools, 8 Middle Schools, 6 OUTLOOK 4 High Schools, and 1 alternative school serves Autism 181 9.1% nearly 31,000 students, and is managed by the Deaf-Blind 1 0.1% By the Numbers Superintendent who is the Executive Secretary of Developmental delay (0-5 only) 37 1.9% SY 2015-2016 a 12 – member Guam Education Board (GEB). Emotionally Disturbed 102 5.1% (as of September 30, 2015) School Performance Report Card The Hearing Impaired 44 2.2% Enrollment purpose of the school report card (P.L. -

Our Mission: to Build a Lifetime Relationship by Enriching Each Member’S Life

ANNUAL REPORT 671.477.8736 www.coast360fcu.com Our Mission: To build a lifetime relationship by enriching each member’s life through exceptional service; and to be stewards of our environment and community for all generations. Over 5,000 network locations to serve you. Federally insured by NCUA. Equal Housing Lender. Members can access their accounts at Your savings are federally insured to at least $250,000 over 5,000 credit union network locations and backed by the full faith and credit of the United throughout the world. States Government. National Credit Union Visit co-opsharedbranch.org for details. Administration, a U.S. Government Agency. meeting minutes hafa adai 54th Annual Membership Meeting • March 29, 2017 Coast360 Federal Credit Union Member Center, Maite, Guam and welcome CALL TO ORDER CHAIRMAN’S REPORT Board of Directors: Pedro R. Martinez and Paul D. members! Leon Guerrero. The Annual Membership meeting was held at the Sheraton Chairman Pedro Martinez presented his message as noted in Laguna Guam Resort in Tamuning, Guam. Chairman of the the 2016 Annual Report of Coast360 Federal Credit Union. The Board Secretary asked for a motion to accept the recommendation of the Nominating Committee Board, Pedro R. Martinez, presided and called the meeting to The Board Secretary called for a motion to accept the for the vacant positions of the Board of Directors Wednesday order at 6:54 p.m. Chairman’s report. Tiffany Quitugua moved to accept the of Coast360 Federal Credit Union. Vincent Duenas Secretary of the Board of Directors, Vicente M. Concepcion, Chairman’s report. Gener Deliquina seconded the motion.