How Schools and Colleges Used the RRRS and Catch-Up Grants for Post-16 Learners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc

Community Profile – Ynyswen, Treorchy and Cwmparc Version 5 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Treorchy is a town and electoral ward in the county borough of Rhondda Cynon Taf in the Rhondda Fawr valley. Treorchy is one of the 16 communities that make up the Rhondda. Treorchy is bordered by the villages of Cwmparc and Ynyswen which are included within the profile. The population is 7,694, 4,404 of which are working age. Treorchy has a thriving high street with many shops and cafes and is in the running as one of the 3 Welsh finalists for Highs Street of the Year award. There are 2 large supermarkets and an Treorchy High Street industrial estate providing local employment. There is also a High school with sixth form Cwmparc Community Centre opportunities for young people in the area Cwmparc is a village and district of the community of Treorchy, 0.8 miles from Treorchy. It is more of a residential area, however St Georges Church Hall located in Cwmparc offers a variety of activities for the community, including Yoga, playgroup and history classes. Ynyswen is a village in the community of Treorchy, 0.6 miles north of Treorchy. It consists mostly of housing but has an industrial estate which was once the site of the Burberry’s factory, one shop and the Forest View Medical Centre. Although there are no petrol stations in the Treorchy area, transport is relatively good throughout the valley. However, there is no Sunday bus service in Cwmparc. Treorchy has a large population of young people and although there are opportunities to engage with sport activities it is evident that there are fewer affordable activities for young women to engage in. -

Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau

Community Profile – Maerdy, Ferndale and Blaenllechau Version 6 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Maerdy Miners Memorial to commemorate the mining history in the Rhondda is Ferndale high street. situated alongside the A4233 in Maerdy on the way to Aberdare Ferndale is a small town in the Rhondda Fach valley. Its neighboring villages include Maerdy and Blaenllechau. Ferndale is 2.1 miles from Maerdy. It is situated at the top at the Rhondda Fach valley, 8 miles from Pontypridd and 20 miles from Cardiff. The villages have magnificent scenery. Maerdy was the last deep mine in the Rhondda valley and closed in 1985 but the mine was still used to transport men into the mine for coal to be mined to the surface at Tower Colliery until 1990. The population of the area is 7,255 of this 21% is aged over 65 years of age, 18% are aged under 14 and 61% aged 35-50. Most of the population is of working age. 30% of people aged between 16-74 are in full time employment in Maerdy and Ferndale compared with 36% across Wales. 40% of people have no qualifications in Maerdy & Ferndale compared with 26% across Wales (Census, 2011). There is a variety of community facilities offering a variety of activities for all ages. There are local community buildings that people access for activities. These are the Maerdy hub and the Arts Factory. Both centre’s offer job clubs, Citizen’s Advice Bureau (CAB) and signposting. There is a sports centre offering football, netball rugby, Pen y Cymoedd Community Profile – Maerdy and Ferndale/V6/02.09.2019 basketball, tennis and a gym. -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

Strictly Confidential

RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL MUNICIPAL YEAR 2019-2020 CHILDREN AND YOUNG PEOPLE SCRUTINY Agenda Item No: 6 COMMITTEE DATE: 22ND JANUARY 2020 Annual School Exclusion Performance Report for the Academic Year 2018/19 REPORT OF: DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION AND INCLUSION SERVICES Author:- Ceri Jones, Head of Inclusion Services (Tel No: 01443 744004) 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide Members with an analysis of school exclusion performance for the academic year 2018/19 and a comparison of performance over the last five years where appropriate. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended that Members: 2.1 Scrutinise and comment on the information contained within this report. 2.2 Consider whether they wish to scrutinise in greater depth any matters contained in the report. 3. BACKGROUND TO THE REPORT 3.1 Schools must have policies and procedures in place that promote good behaviour and prevent poor behaviour. A school’s behaviour and attendance policy should be seen as an integral part of its curriculum, as all schools teach values as well as skills and knowledge. The policy must be based on clear values such as respect, fairness and inclusion, and reflect the school’s overall aims and its social, moral and religious education programmes. 3.2 These values should be the basis for the principles underlying the school’s behaviour and attendance policy. The principles should include promoting self-discipline and respect for others, and the importance of listening to all members of the school community, including the learners. They should be relevant to every member of the school community, including staff, governors and parents/carers. -

Starting School 2018-19 Cover Final.Qxp Layout 1

Starting School 2018-2019 Contents Introduction 2 Information and advice - Contact details..............................................................................................2 Part 1 3 Primary and Secondary Education – General Admission Arrangements A. Choosing a School..........................................................................................................................3 B. Applying for a place ........................................................................................................................4 C.How places are allocated ................................................................................................................5 Part 2 7 Stages of Education Maintained Schools ............................................................................................................................7 Admission Timetable 2018 - 2019 Academic Year ............................................................................14 Admission Policies Voluntary Aided and Controlled (Church) Schools ................................................15 Special Educational Needs ................................................................................................................24 Part 3 26 Appeals Process ..............................................................................................................................26 Part 4 29 Provision of Home to School/College Transport Learner Travel Policy, Information and Arrangements ........................................................................29 -

Rhondda Cynon Taff Bridgend Merthyr Tydfil Vale of Glamorgan

Rhondda Cynon Taff Aberdare Community School Heol-Y-Celyn Primary Ferndale Community School Tonyrefail Community School Ysgol Nant-gwyn Ysgol Llanhari Ysgol Hen Felin (only for pupils requiring special provision) Bridgend Maesteg School Brynmenyn Primary School Maes Yr Haul Primary School Coety Primary School Pencoed Primary School Merthyr Tydfil All schools in Merthyr Tydfil will remain open to support key workers Vale Of Glamorgan Schools will be contacting all parents directly Blaenau Gwent Provision will be made available from Wednesday 25th March Cardiff All schools to open on Monday 23rd March. By the end of the week the Council will then work with schools in light of demand for provision, to set up an appropriate number of hubs across the city. Torfaen Schools will be contacting all parents directly Caerphilly Bedwas Comprehensive Blackwood Primary School Cwm Rhymni Gellihaf Idris Davis Lewis School Pengam Risca Comprehensive Monmouthshire Deri View Primary School Llanfoist Fawr Primary School Dewstow Primary School Rogiet Primary School Overmonnow Primary School Kymin View Primary School Thornwell Primary School Pembroke Primary School Raglan Church in Wales Primary School Newport Cluster High School Provision All individual primary schools are accepting applications from eligible parents of their existing pupils. Year 7 learners can apply for a Bassaleg School place in their former primary school or their closest primary school within the cluster if they are new to the Bassaleg Cluster. All individual schools in the cluster are accepting Caerleon applications from Comprehensive eligible parents of their existing pupils. Alway Primary School will host a childcare facility on Llanwern High behalf of the cluster. -

Community Profile – Pentre

Community Profile – Pentre Version 5 – will be updated and reviewed next on 29.05.20 Pentre is a village and community, near Treorchy in the Rhondda valley. Pentre is 0.7 miles from Treorchy. Ton Pentre, a former industrial coal mining village, is a district of the community of Pentre. The population is 5,210 across the ward but it is important to note that Pentre is the cut off village in the Pen y Cymoedd Community Fund, which does not include Ton Pentre. 17% of the population are under 14; 39% between 35-50 and 8% over 80. 37% of the population are in full time employment. However, 31% of people have no qualifications in Pentre compared with 26% across Llewelyn Street and St Peter’s Church Wales. There are a variety of community facilities and amenities within close proximity of each other. These include Canolfan Pentre, Canolfan Pentre Salvation Army, the Bowls Club and Oasis Church. £81,435 from the Pen y Cymoedd Wind Farm Community Fund has was awarded to Canolfan Pentre to support the installation of a MUGA (Multi Use Games Area) just behind this popular community venue. These centres provide lots of activities for community members. Pentre also has a few shops, petrol station, a pub and a night club. With a children’s park and 3G football pitch at the centre of the village. The 3G pitch can only be used by appointment through the council and Cardiff City children’s development teams are using the pitch weekly. According to Census, (2011) 28% of people have a limiting long-term illness in Pentre compared with 23% across Wales; the nearest GP Surgery is in Ton Pentre (0.6 miles). -

Profile - Rector

The Church in Wales Yr Eglwys Yng Nghymru New Rectorial Benefice of Llantrisant Profile - Rector Contents Contents Pages Summary – the new Benefice 3 - 6 Our Vision 7 - 8 Who we are Llantrisant 9 - 18 Llantwit Fardre 19 - 21 Pontyclun, Talygarn and Llanharry 22 - 26 Llanharan and Brynna 27 - 30 2 The Bishop of Llandaff is seeking to appoint a first Rector for the newly-created Rectorial Benefice of Llantrisant. Our Diocesan Vision We believe faith matters. Our vision is that all may encounter and know the love of God through truth, beauty and service, living full and rich lives through faith. Transforming lives through living and bearing witness to Jesus Christ is our calling. We seek to do this in a Diocese that is strong, confident, alive and living in faith, engaged with the realities of life and serving others in His name. Our profound belief in the sovereignty of God means that we will look to continue Christ’s church and mission by telling the joyful story of Jesus, growing the Kingdom of God by empowering all to participate and building the future in hope and love. Our Shared Aims Telling the joyful story Growing the Kingdom of God Building our capacity for good Llantrisant lies in the centre of the Diocese of Llandaff, approximately 12 miles north-west of Cardiff, the capital city of Wales. From here, it is 20 miles north to the entrance of the Brecon Beacons National Park, and 20 miles south to the beaches and cliffs of the Wales Heritage Coast. It is a historic town, with a Royal Charter dating back to 1346. -

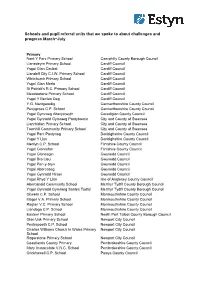

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to About Challenges and Progress March−July

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress March−July Primary Nant Y Parc Primary School Caerphilly County Borough Council Llanedeyrn Primary School Cardiff Council Ysgol Glan Ceubal Cardiff Council Llandaff City C.I.W. Primary School Cardiff Council Whitchurch Primary School Cardiff Council Ysgol Glan Morfa Cardiff Council St Patrick's R.C. Primary School Cardiff Council Meadowlane Primary School Cardiff Council Ysgol Y Berllan Deg Cardiff Council Y.G. Nantgaredig Carmarthenshire County Council Penygroes C.P. School Carmarthenshire County Council Ysgol Gymraeg Aberystwyth Ceredigion County Council Ysgol Gynradd Gymraeg Pontybrenin City and County of Swansea Llanrhidian Primary School City and County of Swansea Townhill Community Primary School City and County of Swansea Ysgol Pant Pastynog Denbighshire County Council Ysgol Y Llys Denbighshire County Council Merllyn C.P. School Flintshire County Council Ysgol Glanrafon Flintshire County Council Ysgol Glancegin Gwynedd Council Ysgol Bro Lleu Gwynedd Council Ysgol Pen-y-bryn Gwynedd Council Ysgol Abercaseg Gwynedd Council Ysgol Gynradd Hirael Gwynedd Council Ysgol Rhyd Y Llan Isle of Anglesey County Council Abercanaid Community School Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Ysgol Gynradd Gymraeg Santes Tudful Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Gilwern C.P. School Monmouthshire County Council Magor V.A. Primary School Monmouthshire County Council Raglan V.C. Primary School Monmouthshire County Council Llandogo C.P. School Monmouthshire County Council Eastern Primary School Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Glan Usk Primary School Newport City Council Pentrepoeth C.P. School Newport City Council Charles Williams Church In Wales Primary Newport City Council School Rogerstone Primary School Newport City Council Coastlands County Primary Pembrokeshire County Council Mary Immaculate V.R.C. -

Starting School Book 2016-17

Starting School 2016-2017 Contents Introduction 2 Information and advice - Contact details..............................................................................................2 Part 1 3 Primary and Secondary Education – General Admission Arrangements A. Choosing a School..........................................................................................................................3 B. Applying for a place ........................................................................................................................4 C.How places are allocated ................................................................................................................5 Part 2 7 Stages of Education Maintained Schools ............................................................................................................................7 Admission Timetable 2016 - 2017 Academic Year ............................................................................14 Admission Policies Voluntary Aided and Controlled (Church) Schools ................................................15 Special Educational Needs ................................................................................................................28 Part 3 31 Appeals Process ..............................................................................................................................31 Part 4 34 Provision of Home to School/College Transport Learner Travel Policy, Information and Arrangements ........................................................................34 -

Schools and Pupil Referral Units That We Spoke to September

Schools and pupil referral units that we spoke to about challenges and progress – August-December 2020 Primary schools All Saints R.C. Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Blaen-Y-Cwm C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Bryn Bach County Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Coed -y- Garn Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Deighton Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Glanhowy Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Rhos Y Fedwen Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Sofrydd C.P. School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Illtyd's Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council St Mary's Roman Catholic - Brynmawr Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Willowtown Primary School Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ysgol Bro Helyg Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Ystruth Primary Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council Afon-Y-Felin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Archdeacon John Lewis Bridgend County Borough Council Betws Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Blaengarw Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Brackla Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryncethin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Bryntirion Infants School Bridgend County Borough Council Cefn Glas Infant School Bridgend County Borough Council Coety Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Corneli Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Cwmfelin Primary School Bridgend County Borough Council Garth Primary School Bridgend -

Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council

RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL CABINET 13 FEBRUARY 2020 CONSIDERATION FOR FAMILY ENGAGEMENT OFFICER ROLES REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR OF EDUCATION AND INCLUSION SERVICES IN DISCUSSIONS WITH THE CABINET MEMBER FOR EDUCATION AND INCLUSION SERVICES (COUNCILLOR MRS J ROSSER) Author: DANIEL WILLIAMS, HEAD OF ATTENDANCE AND WELLBEING SERVICE (Tel: 01443 744298) 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT The purpose of this briefing is to consider the funding and consequent employment of Family Engagement Officers in six secondary/through schools to help tackle school attendance. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended that Members: 2.1 Note the information contained in the report. 2.2 Determine whether to agree to the funding and consequent employment of Family Engagement Officers in six secondary/through schools to help improve attendance. 3. REASONS FOR THE RECOMMENDATIONS 3.1 In the academic year 2018/19, secondary school attendance (including special schools) in RCT declined 0.1% from the previous year to 92.8%. This is the lowest point since the 2012/13 academic year and placed RCT 22nd in the All Wales attendance table. 3.2 As a result of declining figures in recent years, attendance has been made an RCT priority. To ensure that the most vulnerable pupils are supported the Education and Inclusion Services Directorate has identified a model of best practice within our Primary Schools that we believe would be beneficial to supporting attendance as well as forming and enhancing relationships with parents in our lowest performing settings. This model is based around the role of Family Engagement Officers. 4. BACKGROUND 4.1 Family Engagement Officers provide an important link between the school, parents/carers and pupils and have been shown to provide an effective and valued role.