1 Victoria County History of Cumbria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kendal • Croftlands • Ulverston • Barrow from 23 July 2018 Journeys from Kendal & Windermere Towards Barrow Will Operate Via Greenodd Village 6 X6

Kendal • Croftlands • Ulverston • Barrow From 23 July 2018 journeys from Kendal & Windermere towards Barrow will operate via Greenodd village 6 X6 Monday to Saturday excluding Public Holidays Sunday and Public Holidays route number 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 6 X6 6 route number 6 6 6 X6 6 X6 6 X6 6 X6 6 6 6 6 6 journey codes mf l mf l mf mf s sfc v v journey codes v v v v Kendal Bus Station Stand C - - - - - - - 0700 - - 0800 - - 0900 - - 1000 - - - 1100 - - 1200 - - 1300 - Kendal Bus Station Stand C - - - 1130 - 1330 - 1530 - 1730 - - - - - Kendal College - - - - - - - 0705 - - 0805 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - K Village - - - 1133 - 1333 - 1533 - 1733 - - - - - K Village - - - - - - - - - - - - - 0905 - - 1005 - - - 1105 - - 1205 - - 1305 - Helsington Lumley Road - - - 1135 - 1335 - 1535 - 1735 - - - - - Helsington Lumley Road - - - - - - - 0708 - - 0808 - - 0908 - - 1008 - - - 1108 - - 1208 - - 1308 - Heaves Hotel A590 Levens - - - 1141 - 1341 - 1541 - 1741 - - - - - Heaves Hotel A590 Levens - - - - - - - 0714 - - 0814 - - 0914 - - 1014 - - - 1114 - - 1214 - - 1314 - Witherslack Road End - - - 1147 - 1347 - 1547 - 1747 - - - - - Witherslack Road End - - - - - - - 0720 - - 0820 - - 0920 - - 1020 - - - 1120 - - 1220 - - 1320 - Lindale Village - - - 1151 - 1351 - 1551 - 1751 - - - - - Lindale Village - - - - - - - 0724 - - 0824 - - 0924 - - 1024 - - - 1124 - - 1224 - - 1324 - Grange Rail Station - - - 1157 - 1357 - 1557 - 1757 - - - - - Grange Rail Station - - - - - - - 0730 - - 0830 - - 0930 - - 1030 -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Index to Gallery Geograph

INDEX TO GALLERY GEOGRAPH IMAGES These images are taken from the Geograph website under the Creative Commons Licence. They have all been incorporated into the appropriate township entry in the Images of (this township) entry on the Right-hand side. [1343 images as at 1st March 2019] IMAGES FROM HISTORIC PUBLICATIONS From W G Collingwood, The Lake Counties 1932; paintings by A Reginald Smith, Titles 01 Windermere above Skelwith 03 The Langdales from Loughrigg 02 Grasmere Church Bridge Tarn 04 Snow-capped Wetherlam 05 Winter, near Skelwith Bridge 06 Showery Weather, Coniston 07 In the Duddon Valley 08 The Honister Pass 09 Buttermere 10 Crummock-water 11 Derwentwater 12 Borrowdale 13 Old Cottage, Stonethwaite 14 Thirlmere, 15 Ullswater, 16 Mardale (Evening), Engravings Thomas Pennant Alston Moor 1801 Appleby Castle Naworth castle Pendragon castle Margaret Countess of Kirkby Lonsdale bridge Lanercost Priory Cumberland Anne Clifford's Column Images from Hutchinson's History of Cumberland 1794 Vol 1 Title page Lanercost Priory Lanercost Priory Bewcastle Cross Walton House, Walton Naworth Castle Warwick Hall Wetheral Cells Wetheral Priory Wetheral Church Giant's Cave Brougham Giant's Cave Interior Brougham Hall Penrith Castle Blencow Hall, Greystoke Dacre Castle Millom Castle Vol 2 Carlisle Castle Whitehaven Whitehaven St Nicholas Whitehaven St James Whitehaven Castle Cockermouth Bridge Keswick Pocklington's Island Castlerigg Stone Circle Grange in Borrowdale Bowder Stone Bassenthwaite lake Roman Altars, Maryport Aqua-tints and engravings from -

Activities and Groups What's on In...Arnside, Storth, Sandside

01539 728118 What’s On in..... Arnside, Storth, Sandside, Holme, Beetham, Heversham, Burton, Milnthorpe, Levens & Natland Activities and Groups Our groups offer a wide range of activities. Come along to stay healthy, make new friends or even learn a new skill. Gentle Exercises, Natland & Oxenholme Village Every Monday Hall, 2.00 - 3.00pm* (Not 3rd Monday) Gentle Exercises, Arnside Methodist Church Hall, Every Tuesday 9.30 - 10.30am* Gentle Exercises, Arnside Methodist Church Hall, Every Friday 10.30am -12noon* Gentle Exercises, Christ the King Catholic Church, Every Tuesday Milnthorpe, 10.30 - 11.30am* Gentle Exercises, Holme Parish Hall, Every Wednesday 11.00am - 12noon* Gentle Exercises, Levens Methodist Church, Every Wednesday 10.30 - 11.30am* Gentle Exercises, The Athenaeum, Leasgill, Every Thursday 1.30 - 2.30pm* Walking Football, Dallam School 3G Pitch, Every Thursday 6.50 - 7.50pm* (From Sept to March) (From April) Holme Crafters, Holme Parish Hall, 2.30pm* 17 Mar, 21 Apr, 19 May www.ageuk.org.uk/southlakeland/ Mar, April & May 2020 IT Drop-In Sessions, Arnside Educational Every Tuesday Institute, 2.00 - 4.30pm (There will be a donation for the Arnside Educational Institute of £2 for members or £3 for non members) IT Drop In Point, Milnthorpe Library, 3rd Friday 2.00 - 3.30pm IT Drop In Point, Burton Memorial Hall, 1st & 3rd Monday 10.00 - 11.00am Falls Prevention Drop In, Milnthorpe Library, 24 April 10.00am - 12noon Tinnitus Drop In, Age UK South Lakeland, Finkle Every Wednesday Street, Kendal, 10.00am - 12noon Tinnitus Support -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp. -

Open Zone Map in a New

Crosby Garrett Kirkby Stephen Orion Smardale Grasmere Raisbeck Nateby Sadgill Ambleside Tebay Kelleth Kentmere Ravenstonedale Skelwith Bridge Troutbeck Outhgill Windermere Selside Zone 1 M6 Hawkshead Aisgill Grayrigg Bowness-on-Windermere Bowston Lowgill Monday/Tuesday Near Sawrey Burneside Mitchelland Crook Firbank 2 Kendal Lunds Killington Sedburgh Garsdale Head Zone 2 Lake Crosthwaite Bowland Oxenholme Garsdale Brigsteer Wednesday Bridge Killington Broughton-in-Furness 1 Rusland Old Hutton Cartmel Fell Lakeside Dent Cowgill Lowick Newby Bridge Whitbarrow National Levens M6 Middleton Stone House Nature Reserve Foxfield Bouth Zone 3 A595 Backbarrow A5092 The Green Deepdale Crooklands Heversham Penny Bridge A590 High Newton A590 Mansergh Barbon Wednesday/Thursday Kirkby-in-Furness Milnthorpe Meathop A65 Kirksanton Lindale Storth Gearstones Millom Kirkby Lonsdale Holme A595 Ulverston Hutton Roof Zone 4 Haverigg Grange-over-Sands Askam-in-Furness Chapel-le-Dale High Birkwith Swarthmoor Arnside & Burton-in-Kendal Leck Cark Silverdale AONB Yealand Whittington Flookburgh A65 Thursday A590 Redmayne Ingleborough National Bardsea Nature Reserve New Houses Dalton-in-Furness M6 Tunstall Ingleton A687 A590 Warton Horton in Kettlewell Arkholme Amcliffe Scales Capernwray Ribblesdale North Walney National Zone 5 Nature Reserve A65 Hawkswick Carnforth Gressingham Helwith Bridge Barrow-in-Furness Bentham Clapham Hornby Austwick Tuesday Bolton-le-Sands Kilnsey A683 Wray Feizor Malham Moor Stainforth Conistone Claughton Keasden Rampside Slyne Zone 6 Morecambe -

LONGSLEDDALE ESTATE Kendal, La8 9Bb

LONGSLEDDALE ESTATE kendal, la8 9bb LONGSLEDDALE ESTATE kendal, la8 9bb A beautifully situated lakeland Estate generating signif icant hydro-electric income lying within one of the most accessible yet unspoilt dales in the National Park A refurbished Listed principal house 2 hydro-electric schemes producing significant income 98 acres of mowing and grazing land 62 acres of mixed Broadleaf woodland 415 acres of heather moorland and allotment Sporting rights owned over an additional 211 acres with the possibility of leasing rights over another 1,000 acres Double bank fishing on River Mint Potential to create a mixed shoot Total freehold 789 acres including sporting rights For sale in four Lots Kendal 5 miles u M6 motorway (J37) 12 miles (All distances are approximate) Savills Carlisle Savills York 64 Warwick Road River House, 17 Museum Street Carlisle CA1 1DR York, YO1 7DJ [email protected] [email protected] 01228 527586 01904 617800 savills.co.uk savills.co.uk Introduction The sale provides an extremely rare opportunity to acquire a manageable docker nook sized residential, agricultural, sporting and amenity Estate within the Lake District National Park. Longsleddale itself is regarded as one of the least spoilt valleys providing spectacular natural scenery but away from the main tourist routes as the valley is a no-through road. The Estate is very accessible, lying only 5 miles from Kendal with the M6 motorway less then 10 miles to the east making access remarkably easy. The Estate itself lies mainly within a ring fence to the west side of the valley with flat meadow and pasture land bordering the river rising up through the wooded hillside to Dockernook Cragg, a magnificent viewpoint from where the moorland rises gently to approximately 400 metres above sea level at the highest point. -

A Brief History of Kentmere

A Brief History of Kentmere Our story probably begins around 4000BC and it is likely that the first people to inhabit this valley were wandering groups who came here in the later Stone Age. At that time our hills were almost covered in forest and the few animals they had with them would graze along the edge of the wooded areas gradually clearing them. By Roman times much of the forest had been driven back so even in those early days farming had a significant impact upon the landscape and the farmers’ work over centuries eventually led to the attractive patchwork of fields, walls and woodland that we have today. It is probable that the first people to settle here were here came during the Iron Age. They would be Celtic farmers who between 100BC and AD400 built small communities in the valley. Four of these settlements have been discovered. The sites of their huts – although now little more that piles of stone – are still visible. The site at Millriggs is particularly interesting. A glass bracelet dating from AD150 was found there. The Romans came to this part of the world around AD90. They built a fort at Watercrook, Kendal and another at Galava, Ambleside and the road linking them ran through Kentmere. This road would be used by local people as well and perhaps there was a measure of trade with the Roman soldiers. Two places – ‘High Street’ and Broadgate’ show evidence of a paved road above Kentmere to the west although after the Romans left around AD400 the forts and roads all fell into disrepair and ruin. -

For More Routes See

SEDBERGH TO KIRKBY LONSDALE Start/Finish Sedbergh or Kirkby Lonsdale Distance 24 miles (39km). Refreshments Sedbergh, Barbon and Kirkby Lonsdale Toilets Sedbergh, Kirkby Lonsdale Nearest train station Oxenholme near Kendal This is a gentle route exploring the lush Lune Valley connecting the two lively market towns of Sedbergh and Kirkby Lonsdale. 1. Leave Sedbergh on Finkle Street (by the church) signposted to Dent. Straight over mini-roundabout, cross the River Rawthey and then take the first turn on the right signed Sedbergh Golf Course. 2. Go past the golf course, up a short climb and through a gate. At a T-junction turn right. Through a second gate and pass Holme Open Farm. 3. At the junction with the main road, turn left. Follow this road passing under a railway bridge, then turn left by Middleton Hall. 4. Follow this lovely lane for 3.5 miles through to Barbon where there is a pub and the Churchmouse café. Turn left and climb through the village passing the church. Shortly after crossing the cattle grid turn sharp right signposted to Casterton and Kirkby Lonsdale. 5. Follow this road for two miles to where it swings right to cross the old railway. Turn left here signed Cowan Bridge. Take the second turn on the right signed Casterton. Go straight over at the cross roads to reach the A683. 6. Turn left and after 200m you reach a parking area and Devil’s Bridge. Cross this stunning old stone bridge, up past the toilets to reach the busy A65. Push a short distance along the pavement and turn right into Kirkby Lonsdale town centre. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 27 2 LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND REPORT NO. LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Sir Edmund Compton GCB KBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J M Rankin QC MEMBERS Lady Bowden Mr J T Brockbank Professor Michael Chisholm Mr R R Thornton CB DL Sir Andrew Vheatley CBE To the Ht Hon Merlyn Rees, MF Secretary of State for the Home Department PROPOSALS FOK FUTURE ULECTOHAL ARRANGEMENTS FOK THE SOUTH LAKELAND DISTRICT IN THE COUNTY Ot1 CUMBRIA 1. We, the Local Government Boundary Commission for England, having carried out our initial review of the electoral arrangements for South Lakeland district in accordance with the requirements of Section 63 of, and Schedule 9'to, the Local Government Act 1972, present our proposals for the future electoral arrangements for that district. 2. In accordance with the procedure laid down in Section 60(1) and (2) of the T972 Act, notice was given on 19 August 1974 that we were to undertake this review. This was incorporated in a consultation letter addressed to the South Lakeland District Council, copies of which were circulated to Cumbria County Council, parish councils and parish meetings in the district, the Members of Parliament for the constituencies concerned and the headquarters of the main political parties. Copies were also sent to the editors of local newspapers circulating in the area and of the local government press. Notices inserted in the local press announced the start of the review and invited comments from members of the public and from interested bodies. -

Kendal - Sedbergh - Arnside Drive

Kendal - Sedbergh - Arnside drive A drive around south east Cumbria which includes a number of interesting old market towns, picturesque rivers and valleys within the Yorkshire Dales National Park and an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty around Arnside. Arnside Route Map Summary of main attractions on route (click on name for detail) Distance Attraction Car Park Coordinates 0 miles Kendal N 54.33013, W 2.74567 9.1 miles Killington New Bridge N 54.31136, W 2.58144 10.8 miles Brigflatts Meeting House N 54.31638, W 2.55374 12.1 miles Sedbergh N 54.32403, W 2.52606 17.8 miles Dent Village N 54.27835, W 2.45568 22.2 miles Barbondale N 54.24257, W 2.52481 27.7 miles Kirkby Lonsdale N 54.20185, W 2.59654 32.5 miles Hutton Roof Crags N 54.17892, W 2.68776 36.8 miles Lakeland Wildlife Oasis N 54.19400, W 2.75384 38.4 miles Heron Corn Mill N 54.21264, W 2.77482 42.4 miles Arnside Village N 54.20388, W 2.83102 48.2 miles Levens Hall & Gardens N 54.25987, W 2.77526 50.5 miles Sizergh Castle & Gardens N 54.27951, W 2.76822 55.9 miles Kendal N 54.33013, W 2.74567 The Drive Distance: 0 miles Location: Kendal, Westmorland Shopping Centre car park Coordinates: N 54.33013, W 2.74567 The historic market town of Kendal, located at the south east Lake District boundary, is often referred to as ‘the gateway to the Lakes’ due to its position, or ‘the auld grey town’ due to the many old limestone buildings (rather than the climate!). -

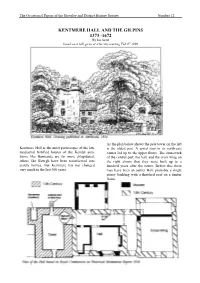

KENTMERE HALL and the GILPINS 1373 -1672 by Joe Scott Based on a Talk Given at a Society Meeting Feb 9Th 1999

The Occasional Papers of the Staveley and District History Society Number 12 KENTMERE HALL AND THE GILPINS 1373 -1672 By Joe Scott based on a talk given at a Society meeting Feb 9th 1999 As the plan below shows the pele tower on the left Kentmere Hall is the most picturesque of the late is the oldest part. A spiral stair in its north-east mediaeval fortified houses of the Kendal area. corner led up to the upper floors. The stonework Some like Burneside are far more dilapidated; of the central part, the hall, and the cross wing on others like Sizergh have been transformed into the right shows that they were built up to a stately homes. But Kentmere has not changed hundred years after the tower. Before this there very much in the last 300 years. may have been an earlier Hall, probably a single storey building with a thatched roof on a timber frame. 2 The tower, with its complex battlements and turrets and its elegant window was built in an age when stone buildings were rare, and when the sandstone for the window surrounds had to be brought from miles away on packhorses. Another striking feature of the Hall is its position. There is no sign of an outer defensive wall, and the site is overlooked from high ground within easy bowshot on three sides. Despite the impressive machicolation, defenders on the roof parapet would have been an easy target. The Hall may have provided some security against a gang of unruly neighbours in the disorderly years of the later Middle Ages, we may suspect from its The main room of the first floor had an elegant position as well as its elegance that its builder was window facing south, a fireplace and a door into thinking more of prestige and status than of real the upper part of the hall, as well as doors to the tactical defence.