Local and State Partnerships with Taxicab Companies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Las Vegas Monorail, an Innovative Solution for Public Transportation Problems Within the Resort Corridor

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 4-1999 The Las Vegas Monorail, an innovative solution for public transportation problems within the resort corridor Cam C. Walker University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Public Administration Commons Repository Citation Walker, Cam C., "The Las Vegas Monorail, an innovative solution for public transportation problems within the resort corridor" (1999). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 198. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1439111 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Monorail 1 THE LAS VEGAS MONORAIL, AN INNOVATIVE SOLUTION The Las Vegas Monorail: An Innovative Solution for Public Transportation Problems within the Resort Corridor By Cam C. Walker Bachelor of Science Brigham Young -

Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD)

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Law ---------------------------------------------------------------------- With corresponding provisions of the Southern California Rapid Transit District Law and Los Angeles County Transportation Commission Law Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority California Public Utilities Code Page 2 of 110 Introduction The Southern California Rapid Transit District, also known as the SCRTD or the “District” (1964-1993) was created by the State as the successor to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transit Authority or “LAMTA” (1958-1964). LAMTA was the first publicly governed transit operator in Los Angeles and also responsible for the planning of a new mass transit system to replace the aging remnants of the transit systems built by Pacific Electric (1899-1953) and Los Angeles Railway (1895-1945). Unfortunately, the LAMTA had no ability to raise tax revenues or powers of eminent domain, and its board was appointed by the Governor, making the task building local support for mass transit improvements difficult at best. Dissatisfaction with the underpowered LAMTA led to a complete re-write of its legislative authority. While referred to in state legislation as a merger, the District law completely overwrote the LAMTA Act of 1957. The Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, also known as LACTC or the “Commission” (1977-1993) was created by the State in 1976 as a separate countywide transportation planning agency, along with transportation commissions in San Bernardino, Riverside, and Orange counties. At the time the District was initially created, there were no transit or transportation grant programs available from the State or Federal governments. Once funding sources became available from the Urban Mass Transit Administration, now the Federal Transit Administration, the California Transportation Commission, and others, the creation of county transportation commissions ensured coordination of multimodal transportation planning and funding programs. -

Rules and Procedures

BOSTON POLICE DEPARTMENT RULES AND PROCEDURES Rule 403 October 30, 2015 HACKNEY CARRIAGE RULES AND REGULATIONS SECTION 1: OVERVIEW I. Definitions a. Boston Police Officer: An individual appointed by the Police Commissioner to carry out the functions of the Boston Police Department, including but not limited to, the preservation of the public peace, the protection of life and property, the prevention of crime, the arrest and prosecution of violators of the law, the proper enforcement of all laws and ordinances and the effective delivery of police services. b. Hackney Carriage: A vehicle used or designed to be used for the conveyance of persons for hire from place to place within the city of Boston, except a street or elevated railway car or a trackless trolley vehicle, within the meaning of Massachusetts General Laws chapter 163 section 2, or a motor vehicle, known as a jitney, operated in the manner and for the purposes set forth in Massachusetts General Laws chapter 159 A, or a sight-seeing automobile licensed under Chapter 399 of the Acts of 1931. Also known as a taxicab or taxi. c. Inspector of Carriages: A superior officer of the Boston Police Department assigned by the Police Commissioner to command the Hackney Carriage Unit. d. Licensed Hackney Driver: An individual, also referred to as a “Driver,” granted a license to operate a Hackney Carriage by the Police Commissioner. e. Medallion Owner: An individual, also referred to as an “Owner,” who has been deemed a suitable individual by the Police Commissioner to own a Hackney Carriage Medallion and who has purchased one or more such Medallions. -

The Canadian Taxi Wars, 1925–1950 Donald F

Document généré le 28 sept. 2021 00:03 Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine The Canadian Taxi Wars, 1925–1950 Donald F. Davis Volume 27, numéro 1, october 1998 Résumé de l'article Entre 1925 et 1950, il y a eu dans la plupart des grandes villes canadiennes une URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1016609ar guerre des taxis qui a fait s’effondrer à la fois les tarifs et les revenus des DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1016609ar chauffeurs. À l’origine de ces guerres : la facilité à entrer dans l’industrie. À la fin des années vingt en effet, les propriétaires de véhicules s’aperçurent que Aller au sommaire du numéro pour faire des profits, ils n’étaient pas obligés d’acheter une concession, de posséder un véhicule construit selon des normes spéciales, de s’équiper d’un central téléphonique et d’un taximètre. Les plus vieilles compagnies qui Éditeur(s) avaient investi dans ces équipements ont réussi en 1950 à persuader les grandes villes canadiennes — y compris Winnipeg et Vancouver, les deux dont Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine il est ici question — d’appliquer l’actuelle réglementation. L’imposition de tarifs uniformes, de taximètres, de salaires minimums, ISSN d’assurance-responsabilité ainsi que de quotas limitant l’accès à l’industrie (par le système des licences) ont réussi à mettre fin aux guerres du taxi. Si 0703-0428 (imprimé) l’industrie a ensuite fonctionné d’une façon moins chaotique et plus éthique, le 1918-5138 (numérique) nouveau régime en a toutefois réduit la souplesse et l’a, par le fait même, rendue moins utile pour le déplacement des masses urbaines. -

A Guide to Paratransit Services

A Guide to Paratransit Services Welcome to DART Mobility Management Services, where it’s our pleasure to serve you! While reading through the pages of this guide, you will get a basic understanding of Paratransit service, what it is, and how it will work for you. Our desire is to provide independence for riders just like those who use DART’s fixed route buses and trains, but are unable to do so. Thank you for giving us the opportunity to provide you with a 5 Star Customer Experience as well as being your transportation provider now and into the future! WHAT IS DART PARATRANSIT SERVICE? DART Paratransit Service is an origin to destination, curb-to-curb, public transportation service for people with disabilities who are unable to use DART fixed route buses or trains. We provide reasonable modification of policy and practice upon request to ensure that our transportation services are accessible to people with disabilities. Paratransit is a shared-ride service operated with modern, accessible vehicles. DART Paratransit also offers a feeder service, for those individuals who can take Paratransit to the nearest bus or rail terminal, and continue to their destination by bus or rail. Feeder service must be taken to the nearest practical bus or rail terminal that will get you to your final destination. For those riders who can use feeder service, the fare is just $0.75 for each one way trip versus $3.00 on a regular Paratransit trip. DART also offers free travel training, along with travel ambassadors, to persons with disabilities who are capable of riding accessible bus and rail services. -

Easychair Preprint New York City Medallion Market's Rise, Fall, And

EasyChair Preprint № 55 New York City Medallion Market's Rise, Fall, and Regulation Implications Sherraina Song EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. April 9, 2018 New York City Medallion Market’s Rise, Fall, and Regulation Implications Sherraina Song Shrewsbury High School, Shrewsbury, MA, 01545, USA [email protected] Abstract. Capping the number of licenses giving exclusive right to street hailing passengers, the New York City medallion system manipulated the demand and supply of taxicab market and made the Yellow Cab medallion not only a commodity of scarcity and but also an investment product hotly pursued. Since 1937, the medallion market evolved and experienced four phases of birth, formation, booming, and collapse and is fighting a losing battle against the newly emerged app-based, ride-sharing service providers like Uber and Lyft. This article presented the findings from mining the data made available by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission, conducted analysis, and argued the deregulation of the New York City taxicab industry has started and that should not and will not be turned back. Keywords: New York City Taxicab, Yellow Cab Taxis, Medallion, Uber, Lyft, TLC, Taxi & Limousine Commission, Green Cab Taxis, For-Hire Vehicle, SHV, App-based, Ride-sharing New York City Taxicab The New York City (NYC) taxicab market is one of about one million passengers per day and annual revenue of two billion US dollars. Thanks to government regulations, there are two sectors of taxicab services in New York City– street hailing and pre- arranged pick-up and three major classes of taxi cabs - Yellow Taxi Cab (Yellow Cab), For-Hire Vehicles (FHVs), and Street Hail Livery (SHL) Street hailer service providers can pick up passengers in response to a street hail. -

Reduced Cost Metro Transportation for People with Disabilities

REDUCED COST AND FREE METRO TRANSPORTATION PROGRAMS FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES Individual Day Supports are tailored services and supports that are provided to a person or a small group of no more than two (2) people, in the community. This service lends very well to the use of public transportation and associated travel training, allowing for active learning while exploring the community and its resources. While the set rate includes funding for transportation, it is important to be resourceful when possible, using available discount programs to make your funds go further. METRO TRANSIT ACCESSIBILITY CENTER The Metro Transit Accessibility Center (202)962-2700 located at Metro headquarters, 600 Fifth Street NW, Washington, DC 20001, offers the following services to people with disabilities: Information and application materials for the Reduced Fare (half fare) program for Metrobus and Metrorail Information and application materials for the MetroAccess paratransit service Consultations and functional assessments to determine eligibility for MetroAccess paratransit service Replacement ID cards for MetroAccess customers Support (by phone) for resetting your MetroAccess EZ-Pay or InstantAccess password The Transit Accessibility Center office hours are 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. weekdays, with the exception of Tuesdays with hours from 8 a.m. - 2:30 p.m. REDUCED FAIR PROGRAM Metro offers reduced fare for people with disabilities who require accessibility features to use public transportation and who have a valid Metro Disability ID. The Metro Disability ID card offers a discount of half the peak fare on Metrorail, and a reduced fare of for 90¢ cash, or 80¢ paying with a SmarTrip® card on regular Metrobus routes, and a discounted fare on other participating bus service providers. -

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA Matthew Barrett Metro Transportation Research Library, Archive & Public Records - metro.net/library Transportation Research Library & Archive • Originally the library of the Los • Transportation research library for Angeles Railway (1895-1945), employees, consultants, students, and intended to serve as both academics, other government public outreach and an agencies and the general public. employee resource. • Partner of the National • Repository of federally funded Transportation Library, member of transportation research starting Transportation Knowledge in 1971. Networks, and affiliate of the National Academies’ Transportation • Began computer cataloging into Research Board (TRB). OCLC’s World Catalog using Library of Congress Subject • Largest transit operator-owned Headings and honoring library, forth largest transportation interlibrary loan requests from library collection after U.C. outside institutions in 1978. Berkeley, Northwestern University and the U.S. DOT’s Volpe Center. • Archive of Los Angeles transit history from 1873-present. • Member of Getty/USC’s L.A. as Subject forum. Accessing the Library • Online: metro.net/library – Library Catalog librarycat.metro.net – Daily aggregated transportation news headlines: headlines.metroprimaryresources.info – Highlights of current and historical documents in our collection: metroprimaryresources.info – Photos: flickr.com/metrolibraryarchive – Film/Video: youtube/metrolibrarian – Social Media: facebook, twitter, tumblr, google+, -

Renewal Licensing Division New Application for Taxicab/Limousine Owner’S License Replacement Provide Vin of Vehicle Being Removed for Replacement______

RENEWAL LICENSING DIVISION NEW APPLICATION FOR TAXICAB/LIMOUSINE OWNER’S LICENSE REPLACEMENT PROVIDE VIN OF VEHICLE BEING REMOVED FOR REPLACEMENT_____________________ A Taxicab/Limousine Owner’s License does not entitle owner to drive a vehicle without also obtaining a Taxicab/Limousine Driver’s License. This application MUST be filled out for each and every taxicab/limousine applied for: Date: __________________________________ Company Name/Owner: _________________________________________________________________________________________________ Address: _________________________________________________________________________________________, the undersigned, hereby applies to the Town of Dover for a license to operate a public taxicab/limousine as desired below within the Town of Dover. The following questions MUST be answered: Home Phone____________________________________ Are you legally eligible to work in the United States? YES NO Business Phone__________________________________ Residential Address:______________________________________________________ Fax No._________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ e-mail address: __________________________________ Attach identification of proof that you are at least 21 years of age. If partnership, the following questions MUST be answered: Give firm name: _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Office Location:_________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Connecticut Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Paratransit Application Form

CT_ADAApplication_Rev8_12-19 Connecticut Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Paratransit Application Form Instructions for Submission To request a copy of this application in an accessible format, please call (203) 365- 8522 Extension 2061. The purpose of this application is to determine eligibility for Connecticut complementary ADA Paratransit service. If you have a disability that prevent s you from using the public transit bus service in Connecticut, you may be eligible for ADA Paratransit service. ADA Paratransit is a shared ride, advanced reservation, origin-to-destination service for persons with disabilities who are unable to use the public bus service because of their disability. Service Criteria The Connecticut ADA Paratransit program is designed to meet the Americans with Disabilities Act service criteria established by the federal government. Service is provided only to individuals f ound eligible by a Connecticut regional ADA service provider and is operated under the following ADA guidelines: • Complementary service is only provided in areas where public buses operate. This does not include Express Commuter service, Intercity or Dial-A-Ride services. ADA Paratransit vehicles can only make pick-ups and drop-offs at places that are within three-quarters of a mile of a public bus route. • Service is provided only during the hours and days when public bus service in that area operates. • Rides must be reserved at least one day inadvance. • ADA Paratransit fares are typically double the cost of a full fare on a public bus route. • Service is not restricted by trip purpose but provided for all types of trips. ADA Definition of Disability Any person with a disability who is unable, as a result of a physical or mental impairment, and without the assistance of another individual (except the operator of a wheelchair lift), to board, ride, or disembark from any public bus. -

Transportation Committee

San Diego Association of Governments TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE June 4, 2004 AGENDA ITEM NO.: 1 Action Requested: APPROVE TRANSPORTATION COMMITTEE DISCUSSION AND ACTIONS Meeting of May 21, 2004 The meeting of the Transportation Committee was called to order by Chair Joe Kellejian (North County Coastal) at 9:10 a.m. See the attached attendance sheet for Transportation Committee member attendance. 1. APPROVAL OF MEETING MINUTES Action: Upon a motion by Councilmember Madaffer (City of San Diego) and a second by Mayor Pro Tem Monroe (South Bay), the Transportation Committee approved the minutes from the May 7, 2004, meeting. Motion Carried. 2. PUBLIC COMMENTS/COMMUNICATIONS/MEMBER COMMENTS None. Chairman Kellejian indicated that due to time constraints, the Committee will now discuss item #6 - Transit Operator Preliminary FY 2005 Budgets and Five-Year Projections. 6. TRANSIT OPERATOR PRELIMINARY FY 2005 BUDGETS AND FIVE-YEAR PROJECTIONS (RECOMMEND As part of SANDAG’s expanded role in the development of transit operator budgets, a series of budget items relating to transit operations has been scheduled through June. In February, the Transportation Committee approved the FY 2005 transit operator guiding principles and objectives, in March the transit operator revenue estimates were approved, and information was provided in April on FY 2004 year-end projections as well as the five- year preliminary projections. This month’s report presents the transit operator preliminary FY 2005 budgets. Staff introduced Paul Jablonski, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the Metropolitan Transit System (MTS), who will discuss MTS’ FY 2005 Budget along with Karen King, Executive Director of the North San Diego County Transit Development Board (NCTD), who will discuss NCTD’s FY 2005 Budget. -

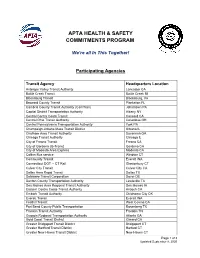

Apta Health & Safety Commitments Program

APTA HEALTH & SAFETY COMMITMENTS PROGRAM We’re all In This Together! Participating Agencies Transit Agency Headquarters Location Antelope Valley Transit Authority Lancaster CA Battle Creek Transit Battle Creek MI Blacksburg Transit Blacksburg, VA Broward County Transit Plantation FL Cambria County Transit Authority (CamTran) Johnstown PA Capital District Transportation Authority Albany NY Central Contra Costa Transit Concord CA Central Ohio Transit Authority Columbus OH Central Pennsylvania Transportation Authority York PA Champaign-Urbana Mass Transit District Urbana IL Chatham Area Transit Authority Savannah GA Chicago Transit Authority Chicago IL City of Fresno Transit Fresno CA City of Gardena (G-Trans) Gardena CA City of Modesto Area Express Modesto CA Collins Bus service Windsor CT Community Transit Everett WA Connecticut DOT -- CT Rail Glastonbury CT Culver City Transit Culver City CA Dallas Area Rapid Transit Dallas TX Delaware Transit Corporation Dover DE Denton County Transportation Authority Lewisville TX Des Moines Area Regional Transit Authority Des Moines IA Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority Antioch CA Embark Transit Authority Oklahoma City OK Everett Transit Everett WA Foothill Transit West Covina CA Fort Bend County Public Transportation Rosenberg TX Franklin Transit Authority Franklin TN Georgia Regional Transportation Authority Atlanta GA Gold Coast Transit District Oxnard CA Greater Bridgeport Transit District Bridgeport CT Greater Hartford Transit District Harford CT Greater New Haven Transit District New Haven