Van De Veer Seminar Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the David Sassoon Industrial School

Volume 11, July 2020 ISSN 2581-5504 “Formulating recommendations to David Sasson Industrial School on the choice of appropriate strategy to help the Juvenile residents” Abhishek Chatterjee LNJN National Institute of Criminology and Forensic Science Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION In welfare state, the major responsibility for setting up correctional institutions for promoting the physical, cultural and emotional growth of children rests primarily with the state and state only. When the family is disrupted and disintegrated, the children fall into antisocial ways and the need arises for keeping them in correctional institutions. A correctional institution for youthful offenders is a place for care, treatment and social re- education of the juvenile who get into trouble with the law. In order to treat antisocial behavior, it becomes expedient to take the child out of his environment and place him in a correctional institution. Such correctional institutions were pioneered by the voluntary organizations in the former State of Bombay. The David Sassoon Industrial School, Bombay (Mumbai), is a juvenile correctional institution managed by the Children’s Aid Society, a voluntary organization. Statements of the problems In 1832, David Sassoon (1792-1864) and his family arrived in Bombay (today Mumbai) after fleeing the persecutions of the ruler of Baghdad, Daud Pasha. This wealthy merchantman, who founded a dynasty known as the “Rothschilds of the East”, was also named the Prince of the Exilarch. David Sassoon began his sojourn in Bombay at 9 Tamarind Street (today non-existent) within the precincts of the city (the Fort walls were destroyed in 1862). He soon moved to Byculla’s bungalow Sans Souci, a former palace named Shin Sangoo, (today Massina Hospital); he also spent the summer months in his second home in Poona (today Pune). -

Mumbai Port Trust Reinforces Sassoon Dock Gate, City's Historic Glory

MUMBAI PORT TRUST Mumbai Port Trust reinforces Sassoon Dock Gate, city’s historic glory. In its endeavor to keep the glorious past of the city of Mumbai preserved in today's time, the MbPT, which shares 141 years long symbiotic relationship with the city, took charge of fortifying the first gateway to the city's sea trade the Sassoon Dock, reaffirming its historic importance.. Excavated out of solid rock by the company of Sir David Sassoon and named after him, the Sassoon Dock situated at Colaba in South Mumbai was the first wet dock accommodation constructed in about 1870 for commercial purposes. Opening of Suez Canal for traffic in November 1869 established a new sea trade route between the Europe and India reducing the distance by half and revolutionized the maritime trade. The first British Merchant vessel making its passage through the Suez Canal ' Glasgow Herald' was berthed at this historic Sassoon Dock. Until construction of the Prince's Dock in 1875-80, the sea trade to the city of Mumbai was carried out from the Sasoon Dock, which could accommodate 5 ships of thousand tonnes each. With the opening of the Prince's Dock for traffic in 1880, Mumbai Port Trust dedicated the Sassoon Dock to the city of Mumbai as a safe heaven for fishing activities by the city's ‘Koli’ Community. One of the most distinguishing features of the Sassoon Dock was its gateway with a centrally built clock tower flanked on either side by the gatehouses. Mumbai Port Trust carried out restorative repairs to the gate structure bringing it back to the original glory and also rejuvenated the historical clock installed in it at a total cost of Rs.25 lakhs. -

A CJP Project Inspire & JDC Entwine Trip: Inside India December 18-27

A CJP Project Inspire & JDC Entwine Trip: Inside India December 18-27, 2018 Participants must stay together as a group at all times and cannot travel around unaccompanied. During our trip to India, we will focus on connecting with and learning about the Bene Israel Indian Jewish community; a geographically isolated, ancient Jewish people primarily based in Mumbai, which traces its roots back to 586 B.C.E. We will travel the Mumbai region together, learn about programs initiated by JDC, and engage in cultural exchange with Indian Jewish young adults. This will allow us to gain a glimpse into different Jewish Indian perspectives and understand a little bit more about this historical community. India has a rich history of religious tolerance, and Jews have been able to practice their faith freely here for over 2,000 years. India’s huge population, extensive levels of poverty, and limited government-run social services have created significant social challenges. This has led to a collaboration between the Jewish community and JDC in which they created a community-based social welfare system. We’ll learn how Israel's work is interwoven throughout this hustling and bustling Indian metropolitan and the different ways in which Israel has become involved in humanitarian aid work and development across this region. Israel and India established full diplomatic relations in 1992. However, even before that, Israel had a Consulate in Mumbai, operating since 1953. Today, India is an important partner to Israel in the areas of politics, commerce, science and culture. MASHAV, Israel’s Agency for International Development Cooperation, was established in 1958 as a manifestation of the Jewish concept of tikkun olam – repairing the world. -

Collaborating and Conflicted- Being Jewish in Secular and Multicultural

Collaborating and Conflicted: Being Jewish in Secular and Multicultural Hong Kong Zhou Xun, University of Essex 1 Hong Kong’s Jewish Film Festival (HKJFF) is Asia’s only Jewish festival. Its current trailer begins with an image tracking a man wearing Djellabas style long dress and hat across the desert. On his journey he is first met by a Chinese girl and then a black man wearing kippah joins them. An Indian woman as well as a Caucasian looking male joins them later. The trailer ends with all of them dancing together. This trailer is based on a story by HKJFF’s founder Howard Elias, a Toronto-born Jew who is now the warden of the Hong Kong Jewish cemetery. It sets out to capture the Jewish experience in Hong Kong, and is a reflection of the multifarious natures of the Hong Kong Jewish communities, as well as Hong Kong society in general. Today there are between six to ten thousand Jews living in this densely populated cosmopolitan city. While the beautiful Edwardian free-baroque style Ohel Leah Synagogue is hailed as one of Asia’s oldest synagogues, Hong Kong is now arguably the center for Jewish life in Asia and the Jewish Community Centre (JCC), in a tall luxury modern apartment tower in 1 I am grateful for the generous helps from Brenda Yi, the librarian of JCC library, and Judy Green, the Chairwoman of Hong Kong Jewish Historical Society, and Elizabeth Sinn who introduced me to them. I am also grateful for the many conversations I had with Sander Gilman while writing this essay. -

Architecture As Social History: Jewish Built Heritage in Bombay and the Konkan

KEY WORDS: Jewish Heritage, Bene Israel, Baghdadi Jew, Bombay, Konkan, Social History Architecture as Social History: Jewish Built Heritage in Bombay and the Konkan Smita Dalvi Tekton Volume 5, Issue 2, September 2018 pp. 50 - 69 ABSTRACT Two distinct Jewish communities flourished in Bombay and the Konkan separated by their time of arrival and their social status- the Bene Israel and the Baghdadi Jews. Both built places of worship and in case of the latter many public buildings. Much of this built heritage survives today Smita Dalvi is a founding faculty of even though the population has dwindled due to outward MES Pillai College of Architecture, Navi migration. This paper attempts to examine the Jewish Mumbai and the editor of Tekton. She architectural heritage in Bombay and the Konkan with has been teaching architecture and an aim to recreate their social and economic history and aesthetics in Navi Mumbai and Mumbai. contribution to public life. In that, two attributes emerge which mark their presence in the social milieu of their times- Her research areas are in Architecture, syncretism and philanthropy. These are indicative of the History of Art & Culture, Urban Heritage architecture’s ability to communicate social characteristics. and has read and published papers and essays in conferences and several In the present time, how the same is perceived and sometime architectural and cultural journals. Her area transformed by the community is also indicative of the of special interest is Islamic architecture changed social scenario. and aesthetics. In 2007, she was awarded the fellowship of ‘Fulbright Visiting Specialist: Direct Access to the Muslim world’. -

HSBC: Flagship Bank of Britain's Dope, Inc

The Bank of Opium HSBC was founded in Hong Kong in 1865 as the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Company by a con- sortium of British opium, silk, and tea-trading compa- HSBC: Flagship Bank nies which themselves were the spawn of the notorious British East India Company. Leading members of the consortium included Jardine Matheson, Dent & Com- Of Britain’s Dope, Inc. pany, David Sassoon & Company, James Innes, and Boston’s Russell & Company. Also supporting the new by John Hoefle bank was the Peninsular and Orient Steam Navigation Company, which itself has a sordid history in the dope July 23—It should come as no surprise that British business. banking giant HSBC was caught laundering money for The opium trade began in the early 1700s as an of- drug cartels and terrorist groups. HSBC, as we shall ficial monopoly of the British East India Company, show, is the kingpin bank of the global drug trade, a which conquered India, and ran it on behalf of the Brit- bank which, since its founding in 1865, has been de- ish Crown and the financiers operating through the City voted to financing drug crops and laundering the pro- of London. Indian-grown opium became a key compo- ceeds. HSBC is, in fact, one of the key controlling in- nent in the trade for tea and silk in China. stitutions of the global illicit drug cartel we call Dope, The East India Company had a thriving business Inc. selling British textiles and other manufactured products If you think that is an outlandish claim, consider the in India, and selling Chinese silk and tea in Britain. -

Bombay 100 Years Ago, Through the Eyes of Their Forefathers

Erstwhile, ‘Bombay’, 100 years ago was beautifully built by the British where the charm of its imagery and landscape was known to baffle all. The look and feel of the city was exclusively reserved for those who lived in that era and those who used to breathe an unassuming air which culminated to form the quintessential ‘old world charisma’. World Luxury Council (India) is showcasing, ‘never seen before’ Collectors’ Edition of 100 year old archival prints on canvas through a Vintage Art Exhibit. The beauty of the archival prints is that they are created with special ink which lasts for 100 years, thus not allowing the colors to fade. The idea is to elicit an unexplored era through paradoxically beautiful images of today’s maximum city and present it to an audience who would have only envisioned Bombay 100 years ago, through the eyes of their forefathers. The splendid collection would be an absolute treat for people to witness and make part of their ‘vintage art’ memorabilia. World Luxury Council India Headquartered in London, UK, World Luxury Council (India) is a ‘by invitation only’ organization which endeavours to provide strategic business opportunities and lifestyle management services though its 4 business verticals – World Luxury Council, World Luxury Club, Worldluxurylaunch.com and a publishing department for luxury magazines. This auxiliary marketing arm essentially caters to discerning corporate clients and high net worth individuals from the country and abroad. The Council works towards providing knowledge, assistance and advice to universal luxury brands, products and services requiring first class representation in Indian markets through a marketing mix of bespoke events, consultancy, web based promotions, distribution and networking platforms. -

Sino-British Conflict Over the Mixed Court, 1884-85 Motono Eiichi Iv

East Asian History NUMBER 12 . DECEMBER 1996 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Far EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie R. Barme Assistant Editor Helen Lo Editorial Board Mark Elvin (Convenor) John Clark Andrew Fraser Helen Hardacre Colin Jeffcott W.]. F. Jenner Lo Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Design and Production Helen Lo Business Manager Marion Weeks Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the twelfth issue of East Asian History in the series previously entitled Paperson Far EasternHistory. The journal is published twice a year. This issue was printed in July 1998. The editors wish to thank colleagues Oanh Collins, Dorothy Mcintosh and Marion Weeks for their generous help in the recovery effort when all electronic copies of this edition were lost in a theft of computers from the BAHeditorial office on the eve of its delivery to the printers. Contributions to The Editor, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Phone +61 26249 3140 Fax +61 26249 5525 email [email protected] Subscription Enquiries to Subscriptions, East Asian History, at the above address Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Tough Guys, Mateship and Honour: Another Chinese Tradition W.]. F.Jenner 35 Chinese Landscape Painting-The Golden Age Ch 'en Chih-mai 51 China in the Eyes of French Intellectuals Jean Chesneaux 65 Lady Murasaki's Erotic Entertainment: The Early Chapters of The Tale of Genji Royall Tyler 79 The "Autocratic Heritage" and China's Political Future: A View from a Qing Specialist Helen Dunstan 105 The Qotong, the Bayad and the Ogeled Ceveng (c. -

What's New Podcast Transcript Season 4, Episode 3, the Last

What’s New Podcast Transcript Season 4, Episode 3: The Last Kings of Shanghai October 27, 2020 Host: Dan Cohen, Dean of Libraries and Vice Provost for Information Collaboration at Northeastern University. Guest: Jonathan Kaufman, Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and author, and Director of the Northeastern University School of Journalism. Host: Dan Cohen (00:08): We have long been told that this will be the Chinese century as the most populous nation in the world achieves economic dominance and as it extends its political influence across the globe. But that still emerging future will also be an extension of China's complex past when other nations arrived on its shores with colonialism, capitalism, and once distant cultures. Today on What's New, how the remarkable story of two Jewish families in Shanghai can tell us a lot about China past, present, and future. Host: Dan Cohen (00:42): Welcome back to What's New, I'm Dan Cohen. With me in the virtual studio is Jonathan Kaufman, the author of a fascinating new book, The Last Kings of Shanghai; The Rival Jewish Dynasties That Helped Create Modern China. Professor Kaufman is a Pulitzer prize, winning reporter and author, and director of the Northeastern University School of Journalism. He has reported on China for three decades for the Boston Globe and the Wall Street Journal. Thanks so much for joining me today, Jonathan, over Zoom in our virtual studio. Jonathan Kaufman (01:14): Thanks, Dan. It's great to be here. Host: Dan Cohen (01:15): Delighted to have you here. -

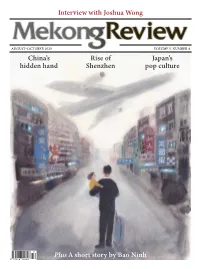

Interview with Joshua Wong Plus a Short Story by Bao Ninh China's

Interview with Joshua Wong AUGUST–OCTOBER 2020 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 4 China’s Rise of Japan’s hidden hand Shenzhen pop culture 32 Plus A short story by Bao Ninh 9 772016 012803 VOLUME 5, NUMBER 4 AUGUST–OCTOBER 2020 HONG KONG 3 Kong Tsung-gan The edict INTERVIEW 5 Elaine Yu Joshua Wong HONG KONG 8 Jeffrey Wasserstrom City on Fire: The Fight for Hong Kong by Antony Dapiran; Aftershock: Essays from Hong Kong by Holmes Chan (ed) POEM 9 Lok Man Law ‘Records of a Floating Island’ CHINA 11 Tom Baxter Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City by Fang Fang POEMS Yuan Changming ‘Woman-radical: A feminist lesson in Chinese characters’; ‘Fragmenting: A sonnet in infinitives’ FOREIGN RELATIONS 12 Michael Reilly Hidden Hand: Exposing How the Chinese Communist Party is Reshaping the World by Clive Hamilton and Mareike Ohlberg SINGAPORE 13 Theophilus Kwek Air-Conditioned Nation Revisited: Essays on Singapore Politics by Cherian George NOTEBOOK 14 Anjan Sundaram Asia matters INDONESIA 15 Lara Norgaard The Jakarta Method: Washington’s Anticommunist Crusade and the Mass Murder Program that Shaped Our World by Vincent Bevins MEMOIR 16 Helen Jarvis First, They Erased Our Name: A Rohingya Speaks by abiburahmanH BIOGRAPHY 17 Gozde Deniz Altunkeser MBS: The Rise to Power of Mohammed bin Salman by Ben Hubbard URBAN AFFAIRS 18 Anne Stevenson-Yang The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City by Juan Du HISTORY 20 Paul French Champions Day: The End of Old Shanghai by James Carter JOURNAL 21 Louis Raymond Personal history FICTION/TRAVEL 23 Emily -

The Sassoon Dynasty

THE SASSOON DYNASTY By CECIL ROTH LONDON ROBERT HALE LIMITED 102 GREAT RUSSELL STREET W.C.1 MCMXLI THE SASSOON DYNASTY By the same author THE LAST FLORENTINE REPUBLIC (London 1925: Italian trnnsbdon, Florence, 1929) THE CASALE PILGRIM (London, 1929) L 1APOTRE DES MARRANES (Paris, 1930) HISTORY OF THE JEWS IN VENICE (Philadelphia,_ 1930: Italictn translation, Rome, 1933) A JEWISH BOOK OF DAYS (!-,ondon, 1931) HISTORY OF THE MARRANOS (Philadelphia, 1932) LETTERE DI DONATO GIANNOTTI A FIERO VETTORI (In collaboration with R. Ridolfi: Florer ce, 1932) THE NEPHEW OF THE ALMIGHTY (London, 1933) A LIFE OF MENASSEH BEN ISRAEL (Philadelphia, 1934) A SHORT HISTORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE (London, 1936) THE SPANISH INQUISITION (London, 1937) THE JEWISH CONTRIBUTION TO CIVILISATION (London 1938: Jugoslav translation, Znghrcb, 1939) THE MAGNIFICENT ROTHSCHILDS (London, 1939) etc. SIR PHILlP SASSOON First Published April r94r Reprinted May r94r PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY WESTERN PRINTING SERVICES LTD., BRISTOL TO ADOLF HITLER FUEHRER OF THE GERMAN REICH FoR TWO reasons I desire to inscribe your name at the beginning of this book. The first is, that I consider its topic to be a useful object,lesson to the unfortunate people whom you have misled into thinking themselves a pure and superior "race" (whatever that may mean). The most rudi, mentary political commonsense should make it obvious that the absorption of gifted foreign families cannot be other than an advantage for a civilized state. England and English life have in particular been enriched for centuries past by receiving fresh elements from other sources, and there can surely be no reason to regret a liberality that has endowed her with soldiers, philanthro, pists and poets such as the Sassoon family and many like it have produced. -

Ebook Download When America First Met China : an Exotic History Of

WHEN AMERICA FIRST MET CHINA : AN EXOTIC HISTORY OF TEA, DRUGS, AND MONEY IN THE AGE OF SAIL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Eric Jay Dolin | 432 pages | 01 Oct 2013 | WW Norton & Co | 9780871406897 | English | United States When America First Met China : An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail PDF Book A rich, highly readable examination of the seeds of poppies, trade, greed, grandeur and an international partnership that remains uneasy and perilous. Olyphant Papers, " PDF. The consul was not recognized by the Chinese authorities or the hope , and was not allowed to fly the American flag over its factory until well after Most of the porcelain dealers in Guangzhou were small, family-run operations with sales of less than 1, taels of merchandise a year, while a few of them could manage to reach an annual gross sale of 10, taels per year. Cushing, in the [[Treaty of Wanghia Treaty of Wanghsia],] in , not only achieved this goal but also won the right of extraterritoriality , which meant that Americans accused of crimes in China were to be tried by American courts only. Here, we have found the best site that is a great resource for anyone who prefers to read books online or download it. Elias David Sassoon. Economic history of China. Archived from the original on From to , faster and larger tea clippers were introduced, thereby replacing the earlier, smaller privateering vessels from the American Revolution. It is a prescient fable for our time, one that surprisingly continues to shed light on our modern relationship with China.