Lebanon Humanitarian Assistance Redevelopment Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf

The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral Report District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher '&# Aley Chouf Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher Georgia Dagher is a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. Her research focuses on parliamentary representation, namely electoral behavior and electoral reform. She has also previously contributed to LCPS’s work on international donors conferences and reform programs. She holds a degree in Politics and Quantitative Methods from the University of Edinburgh. The author would like to thank Sami Atallah, Daniel Garrote Sanchez, John McCabe, and Micheline Tobia for their contribution to this report. 2 LCPS Report Executive Summary The Lebanese parliament agreed to hold parliamentary elections in 2018—nine years after the previous ones. Voters in Aley and Chouf showed strong loyalty toward their sectarian parties and high preferences for candidates of their own sectarian group. -

Appendix a Administrative Boundaries

Lebanon State of the Environment Report Ministry of Environment/LEDO APPENDIX A ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES Lebanon is divided into six Mohafazas, 25 Cazas (excluding Beirut), and 1,492 cadastral zones (see Table A-1). The surface areas in Table A-1 are approximations. Map A-1 depicts the Mohafazas and the Cazas. TABLE A-1 MOHAFAZAS, CAZAS AND CADASTRAL ZONES Number of Surface Area Mohafaza Caza Cadastral Zones (km2) Beirut Beirut 12 19.6 Mount Lebanon 495 1,968.3 ALEY 72 263.7 BAABDA 58 194.3 CHOUF 96 481.2 EL METN 100 263.2 JBAIL 94 430.2 KESROUAN 75 335.7 North 387 2,024.8 AKKAR 133 788.4 MINIEH-DINNIEH 46 409.1 BATROUN 72 287.3 BCHARRE 25 158.2 KOURA 42 172.6 ZGHARTA 52 181.9 TRIPOLI 17 27.3 South 227 929.6 JEZZINE 76 241.8 SAIDA 76 273.7 SOUR 75 414.1 Nabatiyeh 147 1,098.0 BENT JBAIL 38 263.7 MARJAAYOUN 35 265.3 NABATIYE 52 304.0 HASBAYA 22 265.0 Bekaa 224 4,160.9 WEST BEKAA 41 425.4 RACHAYA 28 485.0 HERMEL 11 505.9 ZAHLE 61 425.4 BAALBEK 83 2319.2 TOTAL 1,492 10,201.2 Appendix A. ECODIT Page A. 1 Lebanon State of the Environment Report Ministry of Environment/LEDO MAP A-1 ADMINISTRATIVE BOUNDARIES (MOHAFAZAS AND CAZAS) AKKAR Tripoli North #Y Lebanon HERMEL KOURA MINIEH-DINNIEH ZGHARTA BCHARRE BATROUN BAALBEK BATROUN Mount Bekaa Lebanon KESROUAN Beirut METN #Y BAABDA ZAHLE ALEY CHOUF WEST BEKAA Saida #Y JEZZINE RACHAYA SAIDA South NABATIYEH Lebanon HASBAYA Tyre Nabatiyeh #Y MARJAYOUN TYRE BINT JBEIL Appendix A. -

Usaid/Lebanon Lebanon Industry Value Chain

USAID/LEBANON LEBANON INDUSTRY VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT (LIVCD) PROJECT LIVCD QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT - YEAR 3, QUARTER 4 JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30, 2015 FEBRUARY 2016 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. CONTENTS ACRONYMS ...................................................................................................................................3 YEAR 3 QUARTER 4: JULY 1 – SEPTEMBER 30 2015 ............................................................... 4 PROJECT OVERVIEW .......................................................................................................................................... 4 EXCUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................... 4 QUARTERLY REPORT structure ...................................................................................................................... 5 1. LIVCD YEAR 3 QUARTER 4: RESULTS (RESULTS FRAMEWORK & PERFORMANCE INDICATORS) ................................................................................................................................6 Figure 1: LIVCD Results framework and performance indicators ......................................................... 7 Figure 2: Results achieved against targets .................................................................................................... 8 Table 1: Notes on results achieved .................................................................................................................. -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Wednesday, December 16, 2020 Report #273 Time Published: 08:00 PM New in the report: Recommendations issued by the meeting of the Committee for Follow-up of Preventive Measures and Measures to Confront the Coronavirus on 12/16/2020 Occupancy rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability For daily information on all the details of the beds distribution availablity for Covid-19 patients among all governorates and according to hospitals, kindly check the dashboard link: Computer :https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-PCPhone:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-Mobile All reports and related decisions can be found at: http://drm.pcm.gov.lb Or social media @DRM_Lebanon Distribution of Cases by Villages Beirut 160 Baabda 263 Maten 264 Chouf 111 Kesrwen 112 Aley 121 AIN MRAISSEH 6 CHIYAH 9 BORJ HAMMOUD 13 DAMOUR 1 JOUNIEH SARBA 6 AMROUSIYE 2 AUB 1 JNAH 2 SINN FIL 9 SAADIYAT 2 JOUNIEH KASLIK 5 HAY ES SELLOM 9 RAS BEYROUTH 5 OUZAAI 2 JDAIDET MATN 12 CHHIM 12 ZOUK MKAYEL 14 KHALDEH 2 MANARA 2 BIR HASSAN 1 BAOUCHRIYEH 12 KETERMAYA 4 NAHR EL KALB 1 CHOUIFAT OMARA 15 QREITEM 3 MADINE RIYADIYE 1 DAOURA 7 AANOUT 2 JOUNIEH GHADIR 4 DEIR QOUBEL 2 RAOUCHEH 5 GHBAYREH 9 RAOUDA 8 SIBLINE 1 ZOUK MOSBEH 16 AARAMOUN 17 HAMRA 8 AIN ROUMANE 11 SAD BAOUCHRIYE 1 BOURJEIN 4 ADONIS 3 BAAOUERTA 1 AIN TINEH 2 FURN CHEBBAK 3 SABTIYEH 7 BARJA 14 HARET SAKHR 8 BCHAMOUN 10 MSAITBEH 6 HARET HREIK 54 DEKOUANEH 13 BAASSIR 6 SAHEL AALMA 4 AIN AANOUB 1 OUATA MSAITBEH 1 LAYLAKEH 5 ANTELIAS 16 JIYEH 3 ADMA W DAFNEH 2 BLAYBEL -

The BG News September 20, 1983

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 9-20-1983 The BG News September 20, 1983 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News September 20, 1983" (1983). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4159. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4159 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. vol. 66, issue 13 tuesday, September 20,1983 new/bowling green state university Naval guns open fire in support of Lebanese BEIRUT, Lebanon (AP) - US. na- sea forces. shelling "is the best method to military and the U.S. diplomatic Previously U.S. officials ordered before the naval barrage, but none of val guns hammered away at Druse Druse spokesmen in Beirut claimed achieve" a settlement. corps personnel. The naval gunfire retaliatory shelling after the Marine the 1,200 Americans were injured. artillery positions in Lebanon's cen- the American shells landed in about The destroyer John Rodgers and support missions are defensive ac- camp or other American installations tral mountains yesterday and for the five towns around Souk el-Gharb and the guided missile cruiser Virginia tions." were shelled. The Marines took refuge in sand- first time a U.S. spokesman said the an undetermined number of civilians fired repeated barrages in the morn- A Western military source said the bagged bunkers and foxholes, but firing was in support of the Lebanese were killed. -

AUB Scholarworks

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT IN THE SHADOW OF PLANNING? ECONOMIC AND COMMUNAL INTERESTS IN THE MAKING OF THE SHEMLAN MASTER PLAN by LANA SLEIMAN SALMAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban Planning and Policy to the Department of Architecture and Design of the Faculty of Engineering and Architecture at the American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon January 2014 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis has been in the making for longer than I would like to admit. In between, life happened. I would not have been able to finish this project without the support of many people no acknowledgment would do justice to, but I will try. Mona Fawaz, my thesis advisor, provided patient advice over the years. Throughout our meetings, she continuously added more nuances to this work, and pointed out all the analytical steps I have missed. The rigor and political commitment of her scholarship are admirable and inspirational. Thank you Mona for your patience, and your enthusiasm about this work and its potential. Mona Harb has closely accompanied my journey in the MUPP program and beyond. Her support throughout various stages of this work and my professional career were crucial. Thank you. In subtle and obvious ways, I am very much their student. Hiba Bou Akar’s work was the original inspiration behind this thesis. Her perseverance and academic creativity are a model to follow. She sets a high bar. Thank you Hiba. Nisreen Salti witnessed my evolution from a sophomore at the economics department to a graduate student. Her comments as someone from outside the discipline were enlightening. -

WWF UPDATE WWF Blue School: Mediterranean Fisheries Rural

Participants of the WWF Blue School during a field visit to the Palamós harbour, Spain © WWF-ATW for a living planet R A i VOL 7 NO 2, FEB / MARCH 2007 Posidonia, the WWF Mediterranean newsletter for the community of environmental organizations in the Mediterranean. WWF UPDATE WWF Blue School: Mediterranean fisheries Rural development in Mount Lebanon Training visit in the Middle Atlas, Morocco Progress in the Dinaric Arc DON WWF PRESS Bluefin tuna: on the brink i Slovenia to embark on massive bear hunt Morocco to eliminate driftnet fishing EU’s sustainable energy future UPDATE FROM NGOs Fishing tourism on the Catalan coast Marine stewardship in Catalonia FSC exchange visit Montenegrin NGOs meet with parliament Deconstruction in El Cap de Creus Announcements POS WWF update: Information WWF BLUE SCHOOL – MEDITERRANEAN FISHERIES The latest WWF Mediterranean of Palamós where they met training course took place in the president of the Palamós Sitges, Spain last March. The Fishermen’s Association. At Blue School – Mediterranean the end of the workshop the Fisheries: Linking Ecosystem- participants wrote a manifesto Based Management and on Education for Sustainable Education – brought together Fisheries in the Mediterranean 22 participants and lecturers to express their main from Mediterranean NGOs and concerns, priorities, and institutions to discuss education objectives. for sustainability, environmental The Education for Sustainable education in marine conservation Fisheries in the Mediterranean and its integration in formal manifesto is open to other training programmes for institutions and organizations. The WWF Mediterranean/Across the FOR FURTHER INFORMATION fishermen. Trainees visited Waters training course, Blue School, Montse Suàrez Associació Nereo, a Catalan was supported by the Government Capacity Building Assistant NGO which manages a marine of Catalonia and the Diputació de WWF Mediterranean Barcelona. -

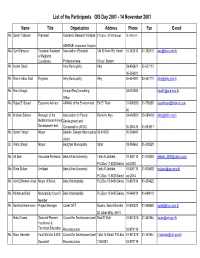

Participants List

List of the Participants GIS Day 2001 - 14 November 2001 Name Title Organization Address Phone Fax E-mail Mr. Samir Traboulsi President Academic Research Institute P.O.Box 155400 Beirut 01-841065 ASHRAE- Lebanese Chapter Ms. Cyril Sahyoun Volunteer Assistant Association d'Entraide 144 El Alam Rd, Horsh 01-382610 01-382610 [email protected] of Regional Coordinator Professionnelle Kfoury, Badaro Mr. Issam Obeid Aley Municipality Aley 03-428621 05-557112 05-554001 Mr. Ramzi Abou Said Engineer Aley Municipality Aley 05-554001 05-557112 [email protected] Mr. Hani Alnaghi Alnaghi Eng Consulting 03-422088 [email protected] Office Ms. Rajaa El Sayed Economic Advisor AMWAJ of the Environment Ein El Tineh 01-806350/ 01-793083 [email protected] 60 Mr. Hisham Salman Manager of the Association for Forest Ramlieh, Aley 03-493281/ 05-280430/ [email protected] Mediterraneab Forest Development and Development and Conservation (AFDC) 05-280430 01-983917 Mr. Samir Fatayri Mayor Baaklin- Swayani Municipality 03-616921 05-304340 Union Dr. Wafic Shaya Mayor Badghan Municipality Safar 03-868662 05-290228 Mr. Ali Bakr Associate Professor Beirut Arab University Tarik Al Jadideh, 01-300110 01-818403 [email protected] P.O.Box 11-5020 Beirut ext 2338 Ms. Rima Sultani Architect Beirut Arab University Tarik Al Jadideh, 01-300110 01-818402 [email protected] P.O.Box 11-5020 Beirut ext 2514 Mr. Abd ElMineam Ariss Mayor of Beirut Beirut Municipality P.O.Box 13-5495 Beirut 01-987014 01-863422 Mr. Mohamad Kadi Municipality Council Beirut Municipality P.O.Box 13-5495 Beirut 01-646318 01-646018 Member Mr. -

Mt Lebanon & the Chouf Mountains ﺟﺒﻞ ﻟﺒﻨﺎن وﺟﺒﺎل اﻟﺸﻮف

© Lonely Planet 293 Mt Lebanon & the Chouf Mountains ﺟﺒﻞ ﻟﺒﻨﺎن وﺟﺒﺎل اﻟﺸﻮف Mt Lebanon, the traditional stronghold of the Maronites, is the heartland of modern Leba- non, comprising several distinct areas that together stretch out to form a rough oval around Beirut, each home to a host of treasures easily accessible on day trips from the capital. Directly to the east of Beirut, rising up into the mountains, are the Metn and Kesrouane districts. The Metn, closest to Beirut, is home to the relaxed, leafy summer-retreats of Brum- mana and Beit Mery, the latter host to a fabulous world-class winter festival. Further out, mountainous Kesrouane is a lunar landscape in summer and a skier’s paradise, with four resorts to choose from, during the snowy winter months. North from Beirut, the built-up coastal strip hides treasures sandwiched between concrete eyesores, from Jounieh’s dubiously hedonistic ‘super’ nightclubs and gambling pleasures to the beautiful ancient port town of Byblos, from which the modern alphabet is believed to have derived. Inland you’ll find the wild and rugged Adonis Valley and Jebel Tannourine, where the remote Afqa Grotto and Laklouk, yet another of Lebanon’s ski resorts, beckon travellers. To the south, the lush green Chouf Mountains, where springs and streams irrigate the region’s plentiful crops of olives, apples and grapes, are the traditional home of Lebanon’s Druze population. The mountains hold a cluster of delights, including one real and one not-so-real palace – Beiteddine and Moussa respectively – as well as the expansive Chouf THE CHOUF MOUNTAINS Cedar Reserve and Deir al-Qamar, one of the prettiest small towns in Lebanon. -

Appeal Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 E-Mail: [email protected]

150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Appeal Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 E-mail: [email protected] Lebanon Coordinating Office LEBANON HUMANITARIAN CRISIS – MELB61 Appeal Target: US$ 6,202,300 Balance Requested from ACT Alliance: US$ 3,992,378 Geneva, 13 September, 2006 Dear Colleagues, On 12 July, Israel launched an offensive against Lebanon following the capture of two of its soldiers by the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah. Israel attacked Hezbollah positions along the border with heavy artillery, tank fire and aerial assaults. For 34 days, the Israeli military operations targeted all regions of Lebanon focusing on the South of Lebanon and the Southern Suburbs of Beirut, a populous, popular and overpopulated area. These regions were already considered in the Lebanese context as very poor. According to the official figures there were 1,287 persons killed, 4,054 injured and 1,200,000 uprooted (25% of the total Lebanese population). 15,000 houses and apartment buildings were completely destroyed and thousands of shops and other constructions severely damaged or destroyed. Basic services such as roads, bridges, energy plants and water were also severely affected. The entire agriculture sector was affected as transport of goods became impossible, export has stopped and most foreign labor escaped because of the shelling. To this should be added the ecological disaster due to the shelling and leakage of around 15,000 tons of fuel oil to the Mediterranean Sea leaving fishermen jobless and without any source of income. On July 27, 2006 an ACT preliminary appeal comprising the ACT/Middle East Council of Churches (MECC) proposal was issued to respond to this emergency. -

DOCO V9N1.Qxd 4/14/2021 2:22 PM Page 1

DOCO Vol21 website_DOCO V9N1.qxd 4/14/2021 2:22 PM Page 1 NEWSLETTER International November 2020 DRUZE ORPHANS & CHARITABLE ORGANIZATION VOL. 21 A Heartfelt We are Beyond Grateful Thank You To Every One Of You OCO would like to thank you for your generous donations during our latest dDrive to help the Druze community in the current unprecedented economic downturn in Lebanon which was intensified by a relentless pandemic. This has left many Druze families financially crippled, unable to afford basic food necessities or personal protective equipment needed to keep the Virus at bay. In addition to the thousands of fami - lies affected, major hospitals caring for our he year 2020 was a difficult year all over Druze brethren continue to be over - the world but for Lebanon it has been whelmed, lacking equipment and supplies. cTatastrophic. The country had already been As donations continue to arrive, we are engulfed in political conflict and civil unrest working hard to expedite the transfer of since 2019, then Covid 19 struck, and an 100% of the funds to your designated char - unprecedented collapse of the country’s ities. With the help of devoted individuals economy and national currency material - and organizations who serve as a bridge ized. When everyone thought it couldn’t get between DOCO and the targeted recipients, any worse, it did, and the explosion of the we were able to alleviate some of the wide - 4th of August happened at the port of spread suffering. Beirut., leaving over 200 dead, 8000 injured So far this year, DOCO has managed and 300,000 homeless. -

WARS and WOES a Chronicle of Lebanese Violence1

The Levantine Review Volume 1 Number 1 (Spring 2012) OF WARS AND WOES A Chronicle of Lebanese Violence1 Mordechai Nisan* In the subconscious of most Lebanese is the prevalent notion—and the common acceptance of it—that the Maronites are the “head” of the country. ‘Head’ carries here a double meaning: the conscious thinking faculty to animate and guide affairs, and the locus of power at the summit of political office. While this statement might seem outrageous to those unversed in the intricacies of Lebanese history and its recent political transformations, its veracity is confirmed by Lebanon’s spiritual mysteries, the political snarls and brinkmanship that have defined its modern existence, and the pluralistic ethno-religious tapestry that still dominates its demographic makeup. Lebanon’s politics are a clear representation of, and a response to, this seminal truth. The establishment of modern Lebanon in 1920 was the political handiwork of Maronites—perhaps most notable among them the community’s Patriarch, Elias Peter Hoyek (1843-1931), and public intellectual and founder of the Alliance Libanaise, Daoud Amoun (1867-1922).2 In recognition of this debt, the President of the Lebanese Republic has by tradition been always a Maronite; the country’s intellectual, cultural, and political elites have hailed largely from the ranks of the Maronite community; and the Patriarch of the Maronite Church in Bkirke has traditionally held sway as chief spiritual and moral figure in the ceremonial and public conduct of state affairs. In the unicameral Lebanese legislature, the population decline of the Christians as a whole— Maronites, Greek Orthodox, Catholics, and Armenians alike—has not altered the reality of the Maronites’ pre-eminence; equal confessional parliamentary representation, granting Lebanon’s Christians numerical parity with Muslims, still defines the country’s political conventions.