Superhero Comics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bill Rogers Collection Inventory (Without Notes).Xlsx

Title Publisher Author(s) Illustrator(s) Year Issue No. Donor No. of copies Box # King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 13 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Mark Silvestri, Ricardo 1982 14 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Villamonte King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 12 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Alan Kupperberg and 1982 11 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Ernie Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench Ricardo Villamonte 1982 10 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group King Conan Marvel Comics Doug Moench John Buscema, Ernie 1982 9 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 8 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1981 6 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Art 1988 33 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Nnicholos King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1981 5 Bill Rogers 2 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema, Danny 1980 3 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Bulanadi King Conan Marvel Comics Roy Thomas John Buscema and Ernie 1980 2 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Group Chan Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar M. Silvestri, Art Nichols 1985 29 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 30 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Geof 1985 31 Bill Rogers 1 J1 Isherwood, Mike Kaluta Conan the King Marvel Don Kraar Mike Docherty, Vince 1986 32 Bill Rogers -

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Melissa Dejesus

Melissa DeJesus Mobile 646 344 2877 Website http://melissade.daportfolio.com/ Email [email protected] Passionate about motivating and inspiring children and teens in expression and critical thinking through the arts using the best in comics, animation, illustration, storytelling and design. Always looking to challenge myself, learn from others, and enjoy teaching others about self representation through art. My interests and skills extend over a vast array of genres and fields of professions. I'm looking to continue my career in education to offer the best of my experience and enthusiasm. Education The School of Visual Arts MAT Art Education 2013-2014 BFA Animation 1998-2002 Employment Harper Collins Publishing 2013-2014 Relevant Comic Illustrator Illustrated 7 page black and white comic excerpt for teen novel. Awesome Forces Productions Fall 2012 Assistant Animator Collaborated with partner in creating animation key frames for animated segments featured in TV series entitled The Aquabats! Super Show! Yen Press 2012-current Graphic Novel Illustrator Illustrated a full color chapters for a graphic novel entitled Monster Galaxy. Created and designed new characters along with existing characters in the online game franchise. Random House 2012-2013 Letterer / Retouch Artist Digitally retouched Japanese graphic novels for sub-division, Kodansha. Lettered 200+ comic pages and designed supplemental pages. Organized and prepared interior book files for print production. King Features Syndicate 2006-2010 Comic Strip Illustrator Digitally illustrated, colored and lettered daily comic strip, My Cage, for newspapers across the country from Hawaii to South Africa. Designed numerous characters on a day to day basis for growing cast. -

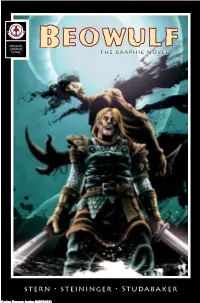

Beowulf: the Graphic Novel Created by Stephen L

ORIGINAL GRAPHIC NOVEL THE GRAPHIC NOVEL TUFSOtTUFJOJOHFSt4UVEBCBLFS Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 THE GRAPHIC NOVEL Writer Stephen L. Stern Artist Christopher Steininger Letterer Chris Studabaker Cover Christopher Steininger For MARKOSIA ENTERPRISES, Ltd. Harry Markos Publisher & Managing Partner Chuck Satterlee Director of Operations Brian Augustyn Editor-In-Chief Tony Lee Group Editor Thomas Mauer Graphic Design & Pre-Press Beowulf: The Graphic Novel created by Stephen L. Stern & Christopher Steininger, based on the translation of the classic poem by Francis Gummere Beowulf: The Graphic Novel. TM & © 2007 Markosia and Stephen L. Stern. All Rights Reserved. Reproduction of any part of this work by any means without the written permission of the publisher is expressly forbidden. Published by Markosia Enterprises, Ltd. Unit A10, Caxton Point, Caxton Way, Stevenage, UK. FIRST PRINTING, October 2007. Harry Markos, Director. Brian Augustyn, EiC. Printed in the EU. Carlos Barrera (order #4973052) 71.204.91.28 Beowulf: The Graphic Novel An Introduction by Stephen L. Stern Writing Beowulf: The Graphic Novel has been one of the most fulfilling experiences of my career. I was captivated by the poem when I first read it decades ago. The translation was by Francis Gummere, and it was a truly masterful work, retaining all of the spirit that the anonymous author (or authors) invested in it while making it accessible to modern readers. “Modern” is, of course, a relative term. The Gummere translation was published in 1910. Yet it held up wonderfully, and over 60 years later, when I came upon it, my imagination was captivated by its powerful descriptions of life in a distant place and time. -

Jeff Lemire Writer Humberto Ramos Penciler Victor

STORM ICEMAN MAGIK COLOSSUS CEREBRA NIGHTCRAWLER JEAN GREY LOGAN IN PURSUIT OF 600 ARTIFICIALLY-CREATED MUTANT EMBRYOS, COLOSSUS AND HIS TEAM OF YOUNG X-MEN WERE TELEPORTED A THOUSAND YEARS INTO THE FUTURE…AND STRANDED ON A DYSTOPIC EARTH MADE IN APOCALYPSE’S IMAGE CALLED “OMEGA WORLD.” WHEN STORM AND HER X-MEN ARRIVED TO AID THEM, THEY FOUND A TRANSFORMED COLOSSUS FIGHTING ALONGSIDE THE HORSEMEN OF APOCALYPSE TO RECLAIM THE ARK. UNFORTUNATELY, THE COMBINED POWER OF THE TWO X-TEAMS WAS NOT ENOUGH TO MAINTAIN POSSESSION OF THE EMBRYOS. NOW, IN A LAST-DITCH EFFORT TO SAVE THEIR SPECIES, THE X-MEN HAVE WALKED DIRECTLY INTO APOCALYPSE’S DOMAIN…AND INTO THE CLUTCHES OF THE FOUR HORSEMEN. JEFF LEMIRE HUMBERTO RAMOS VICTOR OLAZABA EDGAR DELGADO WRITER PENCILER INKER COLOR ARTIST VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA HUMBERTO RAMOS & EDGAR DELGADO LETTERER COVER ARTISTS CHRIS ROBINSON DANIEL KETCHUM MARK PANICCIA AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR X-MEN GROUP EDITOR EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER EXTRAORDINARY X-MEN No. 11, August 2016. Published Monthly except in January by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2016 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. $3.99 per copy in the U.S. -

Mythology Crossword

Name: _____________________________________ Date: _______ Period: _______ Mythology Crossword 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Across 26. images shown in very large view, often 9. large, full page illustration that introduces a 2. objects used to contain a characters thoughts focusing on a small portion of a larger story 6. comics of non-English origin object/character 11. person who does most/all of the art duties, 10. self contained, book length form of comics 27. The space between each panel/panels implies artist is also writer 15. text labels written on characters in comics Down 12. text that speaks directly to reader 16. text / icons that represent what’s going on in 1. objects used to contain words that character 13. images that are in reverse position from the the characters head speaks previous panel 17. images that show objects fully, from top to 3. rectangles where narrator or character shares 14. One drawing on a page containing a segment bottom special info w/ reader of action 18. person who fills speech balloons and captions 4. term popularized by cartoonists, the medium 19. words that indicate a sounds that accompanies with dialogue/other words is capable of mature, non-comedic content, aswell comic panel as to emphasize hybrid nature of the medium 21. Periodical, normally thin in size and stapled 20. A singular row of panels together 5. images that run outside the border of the panel 23. scripts the work in a way that artist can 22. -

Ginal Layouts and a Bonus Silent Issue by Larry Hama and Joe Benitez! Includes G.I

G.I. JOE: SILENT INTERLUDE 30th ANNIVERSARY EDITION presents the story that defined a generation—G.I. JOE: A REAL AMERICAN HERO #21, the famous SILENT INTERLUDE story by Larry Hama and Steve Leialoha. This wordless issue introduced the world to SNAKE EYE’s mysterious nemesis STORM SHADOW and his ARASHIKAGE NINJA—and essays by Mark Bellomo offer a look into the inspiration and creation of this comic book classic. Plus—an unprecedented glimpse of Larry Hama’s original layouts and a bonus silent issue by Larry Hama and Joe Benitez! Includes G.I. JOE: A REAL AMERICAN HERO #21 and G.I. JOE: ORIGINS #19. www.idwpublishing.com • $19.99 G.I. Joe: A ReAl AmeRIcAn HeRo #21: “SIlent InteRlude” StoRy And BReAkdownS By lARRy HAmA FInISHeS By Steve leIAloHA coloRS By GeoRGe RouSSoS G.I. Joe: A ReAl AmeRIcAn HeRo #21: “SIlent InteRlude” oRIGInAl BReAkdownS BReAkdownS By lARRy HAmA G.I. Joe oRIGInS #19: SnAke eyeS StoRy And lAyoutS By lARRy HAmA PencIlS By Joe BenItez InkS By vIctoR llAmAS coloRS By J. BRown IntRoductIon By mARk Bellomo ISSue noteS By mARk Bellomo And lARRy HAmA collectIon coveR By ed HAnnIGAn, klAuS JAnSon, And Romulo FAJARdo JR. oRIGInAl edItS By denny o’neIl, Andy ScHmIdt, And cARloS GuzmAn collectIon edItS By cARloS GuzmAn collectIon deSIGn By cHRIS mowRy Special thanks to Hasbro’s Ed Lane, Joe Furfaro, Heather Hopkins, and Michael Kelly for their invaluable assistance ISBN: 978-1-63140-035-3 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 Ted Adams, CEO & Publisher Facebook: facebook.com/idwpublishing Greg Goldstein, President & COO Robbie Robbins, EVP/Sr. -

Graphic Evangelism 1

Running head: GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 1 Graphic Evangelism The Mainstream Graphic Novel for Christian Evangelism Mark Cupp A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2013 GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Edward Edman, MFA Thesis Chair ______________________________ Chris Gaumer, MFA Committee Member ______________________________ Ronald Sumner, MFA Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 3 Abstract This thesis explores the use of mainstream graphic novels as a means of Christian evangelism. Though not exclusively Christian, the graphic novel, The Beast Within, will educate its target audience by using attractive illustrations, relatable issues, and understandable morals in a fictional, biblically inspired story. This thesis will include character designs, artwork, chapter summaries, and a single chapter of a self-written, self- illustrated graphic novel along with a short summary of Christian references and symbols. The novel will follow six half-human, half-animal warriors on their adventure to restore the balance of their world, which has been disrupted by a powerful enemy. GRAPHIC EVANGELISM 4 Graphic Evangelism The Mainstream Graphic Novel for Christian Evangelism Introduction As recorded in Matthew 28:16-20, all Christians are commanded by Christ to spread the Gospel to all corners of the earth. Many believers almost immediately equate evangelism to Sunday morning services, church mission trips, or distribution of witty, ever-popular salvation tracts; however, Jesus utilized other methods to teach His people, such as telling simple stories and using familiar images and illustrations. -

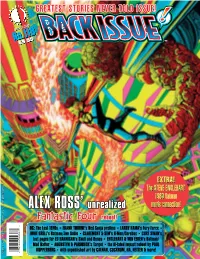

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

Katalog Zur Ausstellung "60 Jahre Marvel

Liebe Kulturfreund*innen, bereits seit Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs befasst sich das Amerikahaus München mit US- amerikanischer Kultur. Als US-amerikanische Behörde war es zunächst für seine Bibliothek und seinen Lesesaal bekannt. Doch schon bald wurde das Programm des Amerikahauses durch Konzerte, Filmvorführungen und Vorträge ergänzt. Im Jahr 1957 zog das Amerika- haus in sein heutiges charakteristisches Gebäude ein und ist dort, nach einer vierjährigen Generalsanierung, seit letztem Jahr wieder zu finden. 2014 gründete sich die Stiftung Bay- erisches Amerikahaus, deren Träger der Freistaat Bayern ist. Heute bietet das Amerikahaus der Münchner Gesellschaft und über die Stadt- und Landesgrenzen hinaus ein vielfältiges Programm zu Themen rund um die transatlantischen Beziehungen – die Vereinigten Staaten, Kanada und Lateinamerika- und dem Schwerpunkt Demokratie an. Unsere einladenden Aus- stellungräume geben uns die Möglichkeit, Werke herausragender Künstler*innen zu zeigen. Mit dem Comicfestival München verbindet das Amerikahaus eine langjährige Partnerschaft. Wir freuen uns sehr, dass wir mit der Ausstellung „60 Jahre Marvel Comics Universe“ bereits die fünfte Ausstellung im Rahmen des Comicfestivals bei uns im Haus zeigen können. In der Vergangenheit haben wir mit unseren Ausstellungen einzelne Comickünstler, wie Tom Bunk, Robert Crumb oder Denis Kitchen gewürdigt. Vor zwei Jahren freute sich unser Publikum über die Ausstellung „80 Jahre Batman“. Dieses Jahr schließen wir mit einem weiteren Jubiläum an und feiern das 60-jährige Bestehen des Marvel-Verlags. Im Mainstream sind die Marvel- Helden durch die in den letzten Jahren immer beliebter gewordenen Blockbuster bekannt geworden, doch Spider-Man & Co. gab es schon lange davor. Das Comic-Heft „Fantastic Four #1“ gab vor 60 Jahren den Startschuss des legendären Marvel-Universums.