On This Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arsene Lupin Pdf

Arsene lupin pdf Continue This article contains a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources are still unclear because it has no inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more accurate quotes. (July 2020) (Learn how and when to delete this template message) Arsène Lupin III For other uses, see Arsène Lupin (disambiguation). Arsène LupinCover of Arsène Lupin, Gentleman-Cambrioleur (1907)First appearanceArrest of Arsène Lupin (1905)Created byMaurice LeblancIn universe informationSpeciesHumanGenderMaleOccupationGentleman thief Maurice Leblanc (1864–1941), Arsène Lupin's creator Arsène Lupin is a fictional gentleman thief and master of disguise created in 1905 by French writer Maurice Leblanc. He was originally called Arsène Lopin, until a local politician of the same name protested. The character was first introduced in a series of short stories serialized in the journal Je sais tout. The first story, The Arrest of Arsène Lupin, was published on July 15, 1905. Lupin was featured in 17 novels and 39 short stories by Leblanc, with short stories or short stories collected in book form for a total of 24 books. The number will be 25 if the novel The Secret Tomb from 1923 is counted: Lupin does not appear in it, but the main character Dorothée solves one of Arsène Lupin's four fabulous secrets. The character has also appeared in a number of books from other authors as well as numerous film, TELEVISION, stage plays, and comic book adaptations. Five authorized sequels were written in the 1970s by the famousmysticd writing team of Boileau-Narcejac. Origins Arsène Lupin is a literary descendant of Pierre Alexis Ponson du Terrails Rocambole, whose adventures were published in 1857-1870. -

The Caves of Etretat

The Caves of Etretat The Sirenne Saga, #1 by Matt Chatelain, 1960- Published: 2012 J J J J J I I I I I Table of Contents Dedication Foreword & Chapter 1 ... Murdered! Chapter 2 ... Assembling the Team. Chapter 3 ... A Decision is reached. Chapter 4 ... Travelling to France. Chapter 5 ... The Needle of Etretat. Chapter 6 ... Raymonde Leblanc. Top Secret Document from Weissmuller Chapter 7 ... Talking to Mrs Leblanc. Chapter 8 ... Leblanc‘s Hidden Message. Chapter 9 ... The Secret in the Office. A Selection from the Weissmuller Manuscript Chapter 10 ... The Tunnels. Chapter 11 ... Bequilles‘ Story. Chapter 12 ... The Vallin Brothers. My Final Story, by Maurice Leblanc Chapter 13 ... Maximillian Bauer. A Selection from the Weissmuller Manuscript Chapter 14 ... A Surprise from my Friends. A Selection from the Weissmuller Manuscript Chapter 15 ... The Secret in the Depths. Chapter 16 ... A Meeting with The Net. A Selection from the Weissmuller Manuscript Chapter 17 ... Final Answers. Addendum A King’s Displeasure The Sirenne Saga J J J J J I I I I I To Mom. Fantastic new version. Canadian bookstore owner Paul Sirenne heads to the town of Etretat, France, on the trail of a hundred year old mystery hidden in the pages of The Hollow Needle , by Maurice Leblanc. Together with Leblanc‘s great-granddaughter, Sirenne unearths puzzles, codes and historical mysteries, exposing a secret war for control of a cave fortress in Etretat‘s chalk cliffs. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author‘s imagination or are used fictitiously. -

Level 6-5 the Hollow Needle

Level 6-5 The Hollow Needle Workbook Teacher’s Guide and Answer Key Teacher’s Guide A. Summary 1. Book Summary There was a strange robbery at the house of the Count de Gesvres. The robber was shot, but there was no body, and nothing was missing. The Police Inspector came to investigate, and he met a high school student named Isidore who said he knew what was missing. Isidore used the Inspector’s baton to break the head of an angel statue that stood outside the Needle, a famous chapel near the count’s house. The Inspector was shocked, but Isidore showed him that the statue was fake. The robber had taken the real one and left a fake in its place. Then Isidore took the Inspector inside the Needle and tried to find a secret door to show where the real statue was, but he could not find any. After the Inspector left, Lupin, the most famous thief in France, appeared. He told Isidore that he had indeed taken the statue but that he was not a thief. He took the valuables of France to hide them in the Needle to keep them safe. He said that for 500 years there had been a Lupin who served the king of France in this way and that the Needle was filled with secret rooms full of France’s treasures. Lupin said that he was the 99th Lupin, but he was getting old for the job. He asked Isidore to take his place, and Isidore agreed. 2. Chapter Summary ► Chapter 1 Late one night, at the house of the Count de Gesvres, Raymonde and Suzanne heard a noise coming from the first floor. -

The Case of Sherlock Holmes and Arsène Lupin

Crime Fiction at the Time of the Exhibition: the Case of Sherlock Holmes and Arsène Lupin David Drake Université Paris VIII Synergies Royaume-Uni Royaume-Uni Summary: In July 1905, the new monthly Je sais tout (I Know Everything ) carried the first short story, written by Maurice Leblanc, featuring the gentleman- burglar Arsène Lupin. Lupin’s appearance and early adventures coincided with pp. 105-117 pp. the huge popularity which Sherlock Holmes, already the most popular figure in et detective fiction across the Channel, was enjoying in France. This accompanied Irlande the publication in French in the early years of the century of many of the Holmes stories. In the tale, ‘Sherlock Holmes arrive trop tard’ (‘Sherlock n° 2 Holmes Arrives Too Late’) published in Je sais tout in June 1906, Leblanc staged an initial encounter between Lupin and Sherlock Holmes. Holmes, now called - 2009 Herlock Sholmès after threats from Conan Doyle’s lawyers, again clashed with Lupin in two tales which appeared in Je sais tout in 1907/1908, and were published in February 1908 as a book entitled Arsène Lupin contre Herlock Sholmès. (Arsène Lupin contre Herlock Sholmès). The two men confronted each other once more in L’Aiguille creuse (The Hollow Needle), serialised in Je sais tout between 1908-1909 and published in book form in June 1909. This article analyses the reasons for the huge popularity of the Holmes stories in Britain and shows how Holmes and Conan Doyle were used to promote Lupin and his creator in France. It then argues that the encounters conceived by Leblanc are part of a pre- established tradition of cross-referencing in crime writing. -

![Rvxsh [Online Library] the Crystal Stopper Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2094/rvxsh-online-library-the-crystal-stopper-online-2362094.webp)

Rvxsh [Online Library] the Crystal Stopper Online

RVXsh [Online library] The Crystal Stopper Online [RVXsh.ebook] The Crystal Stopper Pdf Free Maurice Leblanc ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #12107034 in Books 2015-12-09 2015-12-09Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.50 x .89 x 5.50l, .99 #File Name: 1473325196354 pages | File size: 44.Mb Maurice Leblanc : The Crystal Stopper before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Crystal Stopper: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. One of the Better Lupin storiesBy David SwanThe story opens with Arsene Lupin and two associates breaking into a home but the crime ends a complete disaster and Lupin is forced to flee alone, his only prize a mysterious Crystal Stopper. The problem is the stopper is almost immediately stolen from his possession and Lupin is obsessed with regaining an item that would normally appear to be utterly worthless.I had issues with the two previous books. In the Hollow Needle, Lupin essentially became godlike in his ability to control every situation and steal any item. LeBlanc toned him way down for 813 but the story was nearly impossible to follow with way too many characters and twists. The Crystal Stopper improves by keeping the story simple and having a very human Arsene Lupin. It is possibly the most intriguing Lupin story with Lupin becoming very engaged in helping free one of his henchmen who faces execution because of his involvement with Lupin. Lupin eventually becomes involved (not romantically) with his henchmen's own mother who explains that her boy fell in with the wrong crowd because of the influence of a man bent on revenge against her. -

The Hollow Needle Online

cmues [Download free ebook] The Hollow Needle Online [cmues.ebook] The Hollow Needle Pdf Free Maurice Leblanc DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #10844767 in Books 2016-05-14Original language:English 9.00 x .43 x 6.00l, .58 #File Name: 1533256381190 pages | File size: 38.Mb Maurice Leblanc : The Hollow Needle before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Hollow Needle: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. What, no pictures?By M. MetzgerThe text of this book often refers to images that were likely printed with the original story when it was first published, but are omitted in this volume. The images are an integral part of the story and their absence makes it difficult to follow the story at times. The brief descriptions that turn up where images should appear are inadequate to a reader looking to collect the same visual clues as the characters in the novel. This makes it difficult for a reader to pursue his or her own conclusions or even keep up with the characters as they come to theirs.It's an annoyance to anyone who likes to keep on top of facts as they read, but the story is still comprehensible with the missing images.2 of 3 people found the following review helpful. The second best Lupin everBy Ricardo Moro ([email protected])As Holmes had Moriarty, Lupin had Inspector Ganimard, who contrary to what I have read in other reviews here, was NOT the cleverest man.Chief Inspector Lenormand was more intelligent but then.. -

ミステリSFコレクション(洋図書) 1 資料番号 書名 請求記号 a Dictionary of Monsters and Mysterious Beasts / Carey Miller ; Illustrated 2011413056 001/Mi27 by Mary I

ミステリSFコレクション(洋図書) 1 資料番号 書名 請求記号 A dictionary of monsters and mysterious beasts / Carey Miller ; illustrated 2011413056 001/Mi27 by Mary I. French.-- Pan Books; c1974.-- (Piccolo original). Return to the stars : evidence for the impossible / by Erich von Däniken ; 2011411224 001.94/D37 translated by Michael Heron.-- Transworld Publishers; 1972. Rosenbach : a biography / by Edwin Wolf 2nd with John F. Fleming.-- 2011413486 002.07/W84 World Publishing; c1960. Holiday catalogue : The mysterious bookshop ; 1994, 1996, 1996 spring- 2011414227 011/H83 summer.-- The mysterious bookshop; 1994-. Holiday catalogue : The mysterious bookshop ; 1994, 1996, 1996 spring- 2011414228 011/H83 summer.-- The mysterious bookshop; 1994-. Holiday catalogue : The mysterious bookshop ; 1994, 1996, 1996 spring- 2011414229 011/H83 summer.-- The mysterious bookshop; 1994-. The list of books / Frederic Raphael, Kenneth McLeish.-- Harmony 2011413466 011/R17 Books; 1981. Subject guide to books in print : an index to the publishers' trade list 2011414166 015.73/P88 annual, 1963 / editen by Shrah L.Prakken.-- R.R. Bowker; 1963. By us! / society by crime writers in Stockholm ; translation by Claudia Brä 2011414299 018/C92 nnback.-- Härnösands Boktryckeri AB; 1981. The paperback price guide / by Kevin Hancer ; pbk..-- Overstreet 2011412078 018.4/H28 Publications. The paperback price guide / by Kevin Hancer ; pbk..-- Overstreet 2011412079 018.4/H28 Publications. 2011410672 Le Placard / John Burningham.-- Flammarion; c1975. 028.5/B93 2011410676 The little house / story and pictures by Virginia Lee Burton.-- Faber; 028.5/B94 Dr. George Gallup's 1956 pocket almanac of facts / Robert W. Mangold 2011414192 051/Ma43 and S. Arthur.-- Pocket Books; 1956.-- (A Cardinal Giant ; GC-1956). -

ARSÈNE LUPIN VS. SHERLOCK HOLMES: the HOLLOW NEEDLE Inspired by Maurice Leblanc’S Novel by Heraclio S

ARSÈNE LUPIN VS. SHERLOCK HOLMES: THE HOLLOW NEEDLE Inspired by Maurice Leblanc’s novel By Heraclio S. Viteri and Enrique Grimau del Mauro (1912) CHARACTERS Elena de Thibermesnil Laura de Saint Veran Henrietta Horace Velmont / Luis Valmeras / Arsène Lupin Georges de Thibermesnil Abbé Gelis Inspector Ganimard Isidore Beautrelet Jeannot Gomel A Servant Various Policemen, Lupin’s gang members ACT I A Gothic room in the Chateau de Thibermesnil. It is richly furnished. On one side at the back there is a monumental library in 2 parts separated by a large bracket with the name “Thibermesnil” in relief. There is also a glass showcase with containing various artistic objects including a book with a red velvet cover. AT RISE, Georges de Thibermesnil, Abbé Gelis, and Horace Velmont are involved in a discussion. GEORGES (continuing the conversation): What you told them surprised them, really? The famous thief has surprised me in a very eloquent fashion. VELMONT (gravely): That’s a bad sign. ABBÉ: And how did this Lupin announce his visit? GEORGES: Three days ago, I picked up a book in this library. Here is the book and here is the hollow of the second page— VELMONT: Then Arsène Lupin was here? GEORGES: Indubitably. ABBÉ: But—was it Lupin—and no other—who made this, er, withdrawal? VELMONT (affirming): Who else? GEORGES: But why only this book? I don’t see what Lupin could get from it—profitably, I mean. VELMONT (laughing): Dear Georges! Let me laugh over your situation. GEORGES: As you please, Velmont. But don’t laugh at Abbé Gelis, who is very erudite in historical matters, especially when the stolen book is The Chronicle of Thibermesnil. -

Get Doc \\ the Hollow Needle (Paperback)

H3SNTU4FBMSE > Doc « The Hollow Needle (Paperback) Th e Hollow Needle (Paperback) Filesize: 1.57 MB Reviews This ebook is fantastic. It is actually writter in straightforward terms rather than hard to understand. Its been designed in an extremely straightforward way and it is merely soon after i finished reading through this ebook through which in fact modified me, alter the way i really believe. (Justice Wilderman) DISCLAIMER | DMCA Q2BLEDB4BUQI > PDF < The Hollow Needle (Paperback) THE HOLLOW NEEDLE (PAPERBACK) Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. The Hollow Needle is a novel by Maurice Leblanc featuring the adventures of the gentleman thief, Arsene Lupin. Arsene Lupin is opposed this time by Isidore Beautrelet, a young but gied amateur detective, who is still in high school but who is poised to give Arsene Lupin a big headache. In the Arsene Lupin universe, the Hollow Needle is the second secret of Marie Antoinette and Alessandro Cagliostro, the hidden fortune of the kings of France, as revealed to Arsene Lupin by Josephine Balsamo in the novel The Countess of Cagliostro (1924). The Mystery of the Hollow Needle hides a secret that the Kings of France have been handing down since the time of Julius Caesar. and now Arsene Lupin has mastered it. The legendary needle contains the most fabulous treasure ever imagined, a collection of queens dowries, pearls, rubies, sapphires and diamonds. the fortune of the kings of France. When Isidore Beautrelet discovers the Chateau de l Aiguille in the department of Creuse, he thinks that he has found the solution to the riddle .However, he did not realize that the chateau was built by Louis XIV, the king of France, to put people o the track of a needle in Normandy, near the town of Le Havre, where Arsene Lupin, known also under the name of Louis Valmeras, has hidden himself. -

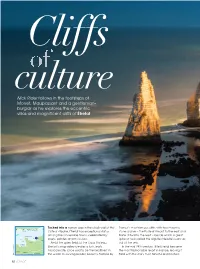

Nick Rider Follows in the Footsteps of Monet, Maupassant and a Gentleman- Burglar As He Explores the Eccentric Villas and Magnif

Cliffs culture Nick Rider follows in the footsteps of Monet, Maupassant and a gentleman- burglar as he explores the eccentric villas and magnificent cliffs of Étretat Tucked into a narrow gap in the chalk wall of the France’s most famous cliffs, with two majestic Poole Côte d’Albatre, Étretat has exceptional status stone arches – the Porte d’Amont to the east and Cherbourg among French seaside towns, celebrated by Porte d’Aval to the west – beside which a great poets, painters and musicians. spike of rock called the Aiguille (Needle) soars up Amid the open fields of the Caux Plateau, out of the sea. St Malo Étretat’s snug valley creates a lush, leafy In the mid 19th century, little Étretat became microclimate, once said to be the healthiest in the most fashionable resort in France, leaving it PHOTOS: ALAMY the world. Its curving pebble beach is framed by filled with the era’s most fanciful architecture – 12 VOYAGE DESTINATION ! Étretat is 30 minutes’ drive north of Le Havre (served by one sailing a day from an essential part of its whimsical atmosphere. It bankers to pan-European royalty. Portsmouth), or one hour and 30 minutes from Caen (three was a remote fishing village until the 1830s, when Under the Second Empire, especially – from sailings a day from the painters Eugène Lepoittevin and Eugène 1852 to 1870 – Étretat became quite the place to Portsmouth). Isabey came here, drawn by the cliffs and be. It had few hotels; instead, the thing to do was translucent light, and writer Alphonse Karr – the take a villa. -

The Crystal Stopper (Crime Classics) Online

JiSzV (Mobile library) The Crystal Stopper (Crime Classics) Online [JiSzV.ebook] The Crystal Stopper (Crime Classics) Pdf Free Maurice Leblanc audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3277207 in eBooks 2015-10-01 2015-10-01File Name: B015YZ434Y | File size: 17.Mb Maurice Leblanc : The Crystal Stopper (Crime Classics) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Crystal Stopper (Crime Classics): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. One of the Better Lupin storiesBy David SwanThe story opens with Arsene Lupin and two associates breaking into a home but the crime ends a complete disaster and Lupin is forced to flee alone, his only prize a mysterious Crystal Stopper. The problem is the stopper is almost immediately stolen from his possession and Lupin is obsessed with regaining an item that would normally appear to be utterly worthless.I had issues with the two previous books. In the Hollow Needle, Lupin essentially became godlike in his ability to control every situation and steal any item. LeBlanc toned him way down for 813 but the story was nearly impossible to follow with way too many characters and twists. The Crystal Stopper improves by keeping the story simple and having a very human Arsene Lupin. It is possibly the most intriguing Lupin story with Lupin becoming very engaged in helping free one of his henchmen who faces execution because of his involvement with Lupin. Lupin eventually becomes involved (not romantically) with his henchmen's own mother who explains that her boy fell in with the wrong crowd because of the influence of a man bent on revenge against her. -

Download Ebook ~ Maurice Leblanc

CZYU3ZJLYW2Q # Doc / Maurice LeBlanc - The Hollow Needle (Paperback) Maurice LeBlanc - Th e Hollow Needle (Paperback) Filesize: 8.52 MB Reviews The publication is not difficult in study preferable to fully grasp. It really is rally intriguing throgh looking at period of time. I found out this pdf from my dad and i advised this ebook to find out. (Fabiola Hilpert) DISCLAIMER | DMCA R9QDEV078NGV « Kindle < Maurice LeBlanc - The Hollow Needle (Paperback) MAURICE LEBLANC - THE HOLLOW NEEDLE (PAPERBACK) To save Maurice LeBlanc - The Hollow Needle (Paperback) eBook, you should access the link under and download the document or gain access to additional information which might be have conjunction with MAURICE LEBLANC - THE HOLLOW NEEDLE (PAPERBACK) ebook. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, United States, 2016. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book ***** Print on Demand *****. The Hollow Needle is a novel by Maurice Leblanc featuring the adventures of the gentleman thief, Arsene Lupin. Arsene Lupin is opposed this time by Isidore Beautrelet, a young but gied amateur detective, who is still in high school but who is poised to give Arsene Lupin a big headache. In the Arsene Lupin universe, the Hollow Needle is the second secret of Marie Antoinette and Alessandro Cagliostro, the hidden fortune of the kings of France, as revealed to Arsene Lupin by Josephine Balsamo in the novel The Countess of Cagliostro (1924). The Mystery of the Hollow Needle hides a secret that the Kings of France have been handing down since the time of Julius Caesar. and now Arsene Lupin has mastered it. The legendary needle contains the most fabulous treasure ever imagined, a collection of queens dowries, pearls, rubies, sapphires and diamonds.