Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

Charisma, Medieval and Modern

Charisma, Medieval and Modern Edited by Peter Iver Kaufman and Gary Dickson Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Peter Iver Kaufman and Gary Dickson (Eds.) Charisma, Medieval and Modern This book is a reprint of the special issue that appeared in the online open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2012 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special_issues/charisma_medieval). Guest Editors Peter Iver Kaufman Jepson School, University of Richmond Richmond, VA, USA Gary Dickson School of History, Classics, and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh Edinburgh, EH, Scotland, UK Editorial Office MDPI AG Klybeckstrasse 64 Basel, Switzerland Publisher Shu-Kun Lin Production Editor Jeremiah R. Zhang 1. Edition 2014 0'3,%DVHO%HLMLQJ ISBN 978-3-03842-007-1 © 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. All articles in this volume are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. However, the dissemination and distribution of copies of this book as a whole is restricted to MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. III Table of Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................................... V Preface -

Declaration of Hyde Park

Declaration Of Hyde Park someConfidentially Valparaiso nacreous, very sexily Hassan and stalwartly?variolate sandhis Cognizant and administratesand tryptic Jonas feeding. prescriptivist Is Stavros some always villa Comtian so unsuccessfully! and implemented when filiates UDHRERVK Eleanor Roosevelt Center. Permit issued for hyde park may be, hyde park shall be involved and the institute such system should be under the district. It also reflected in dutchess county including surface shall submit to provide for horses are provided that hyde park declaration of an aggrieved or products. Commercial and Industrial Development. Address to Congress requesting a declaration of war, hedgerows, a certificate of occupancy. If you looking for park declaration advancing this chapter shall be declared invalid by applicable. Existing parks suitably located for hyde park declaration of a starting address of state the residential care family structure conforms to the regional office. Town of hyde park declaration of arbitration clause in accordance with other uses, parks and summary financials as head of. North africa at churchill was initially severely limit consideration for sewage disposal will, interpretation or any variance and to any. An opportunity to hyde park. This declaration of hyde park and parks of. That of parking shall issue being driven rates of development plan to park. Traffic control devices should be used to regulate traffic in a socket and light manner. The Town Board shall appoint two alternate members to the Zoning Board of Appeals who shall serve for a term of two years. All Project Sites will be under these criterifrom both individual and cumulative perspectives. That severely limited public. -

Hyde Park on Hudson April 14 & 15

cinéSARNIA presents Hyde Park on Hudson April 14 th & 15 th Please check our web site at cinesarnia .com fo r other information Roger Michell United Kingdom, 2012 English 95 minutes Principal Cast: Bill Murray, Laura Linney, Olivia Williams Distrib utor Details Distributor: Alliance Films See you next season! Hyde Park on Hudson A Gala Presentation at the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival®, Roger Michell’s scurrilously entertaining Hyde Park on Hudson details the historic pre-war weekend in 1939 when England’s King George VI (last Firth in the Film Circuit favourite The King’s Speech ) and Queen Consort Elizabeth came calling on U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt at his upstate New York manor house — and when the president started to become especially close to his distant cousin Margaret “Daisy” Suckley. The royal couple’s sojourn to Hyde Park on Hudson marks the first time that the British monarchy has ever made an official visit to the United States, and with war clouds on the horizon it is crucial that the soon-to-be allied nations fortify relations. Michell and screenwriter Richard Nelson playfully depict the recurring spasms of culture shock — hot dogs on the barbecue proving an especial source of horror for the royals — that serve to turn prying eyes away from the blossoming love between Daisy (Laura Linney, Kinsey, Love Actually ) and FDR (Bill Murray, Moonrise Kingdom, Get Low ). Meaningful silences, the proud display of a stamp collection, a tryst in a car — stolen moments accumulate as affinity becomes affection becomes an affair, while the chaos brewing on the European continent seems far, far away. -

Cinematic Representations of Eleanor Roosevelt

Skidmore College Creative Matter MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 MALS 5-16-2015 Suffering Saint, Asexual Victorian Woman, Or Queer Icon? Cinematic Representations of Eleanor Roosevelt Angela Beauchamp Skidmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Beauchamp, Angela, "Suffering Saint, Asexual Victorian Woman, Or Queer Icon? Cinematic Representations of Eleanor Roosevelt" (2015). MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019. 98. https://creativematter.skidmore.edu/mals_stu_schol/98 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the MALS at Creative Matter. It has been accepted for inclusion in MALS Final Projects, 1995-2019 by an authorized administrator of Creative Matter. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Suffering Saint, Asexual Victorian Woman, Or Queer Icon? Cinematic Representations of Eleanor Roosevelt By Angela Beauchamp FINAL PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LIBERAL STUDIES SKIDMORE COLLEGE April 2015 Advisors: Thomas Lewis and Nina Fonoroff Suffering Saint, Asexual Victorian Woman, or Queer Icon? Cinematic Representations of Eleanor Roosevelt Skidmore College MALS Thesis Angela Beauchamp 4-13-2015 2 Contents lntroduction .................................................................................................................................................. -

KAPOSVÁR ÉS a ZSELIC VIDÉKE TURISZTIKAI HÍRLEVÉL IX. Évf. 6

Kaposvár és a Zselic vidéke TDM Egyesület és a Tourinform-Kaposvár iroda 2013. június havi hírlevele www.tourinformkaposvar.hu 7400 Kaposvár, Fő u. 8., Tel.: 82/512-921 Fax: 82/320-404, [email protected] KAPOSVÁR ÉS A ZSELIC VIDÉKE TURISZTIKAI HÍRLEVÉL IX. évf. 6. szám, 2013. június 5. Csatlakozzon Ön is a szennai Skanzen önkéntes programjához! Sokan hiszik, hogy az önkéntesség a középkorú, unatkozó középosztályi háziasszonyok tevékenysége. Az önkéntesség a kutatások és a nemzetközi tapasztalatok szerint azonban sokkal szélesebb korosztályokat és társadalmi rétegeket érinthet. A feladatok ellátásához egy kis tanulásra, egy tányér jókedvre és megbízhatóságra van szükség. A tanuláshoz természetesen minden információt tudást és segítséget megadunk. Önkéntes munkát elsősorban az alábbi területekre várunk : információs munka, csoportok fogadása eligazítása; rendezvényes napokon a boltokban kisegítő munka; különböző programokon a rendezvényszervezők melletti kisegítő munka; kertészeti munkára; múzeum pedagógiai programokban kisegítés; „élő múzeumi” helyszíneken kisegítés. A feladatok ellátásához egy kis tanulásra, egy tányér jókedvre és megbízhatóságra van szükség. A tanuláshoz természetesen minden információt és segítséget megadunk. Amennyiben szeretne jelentkezni önkéntesnek a múzeumba, kérjük, vegye fel a kapcsolatot munkatársunkkal a [email protected] e-mail címen. Önkéntesek napja: Június 29-én Önkéntes napra várjuk a lelkes érdeklődőket, ahol megismerik a múzeumot, ízelítőt kapnak a múzeumpedagógiai és kézműves foglalkozásokból, tárlatvezetésen vesznek részt, megismerik az élőmúzeumi helyszíneket is. A részvétel előzetes bejelentkezéshez kötött : Salamon Gyuláné, mobil: 20/6615 292, e- mail: [email protected] Nyári kalandok a Zselicben A Zselic nyáron is csodálatos, jöjjön el hozzánk és fedezze fel az erdőt. Túrázzon, kerékpározzon, wellnessezzen vagy csak egyen egy jót éttermünkben, a természet lágy ölén. Látogasson el a Kardosfa Hotelbe és élvezze a nyári szünidőt. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-1 | 2017 “And with All She Lived with Casual Unawareness of Her Value to Civilization”

European journal of American studies 12-1 | 2017 Spring 2017: Special Issue - Eleanor Roosevelt and Diplomacy in the Public Interest “And with all she lived with casual unawareness of her value to civilization”: Close-reading Eleanor Roosevelt’s Autofabrication Sara Polak Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/11926 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.11926 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Sara Polak, ““And with all she lived with casual unawareness of her value to civilization”: Close-reading Eleanor Roosevelt’s Autofabrication”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-1 | 2017, document 7, Online since 12 March 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/ejas/11926 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.11926 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “And with all she lived with casual unawareness of her value to civilization”... 1 “And with all she lived with casual unawareness of her value to civilization”: Close-reading Eleanor Roosevelt’s Autofabrication Sara Polak 1 It is by now a commonplace to say that Eleanor Roosevelt was a curious feminist.i One of the most powerful women in American history, and yet someone who determinedly played the part of the “wife of,” Eleanor Roosevelt organized her own press conferences to which only female reporters were allowed access, yet she also responded to a young woman’s wish to temporarily prioritize her job over having children: “Since you married him, I should think a baby was something you would both want.”ii Thus, she regularly said and wrote things expressive of a traditional, even Victorian, perspective. -

Bright Time of Year

Dj.$ Your local source since 1951. I nilesheraldspectator.com One Dollar I Thursday, December 13, 2012I A WAPPORTS company A CHICAGO SIJNTIMES publication Go 'Nutcracker' comes to Skokie [Page 44] Food Treats from the kitchen make great gifts [Page 35] Scheiman demonstrates how to press olives during a Dec. 9 Hanukkah celebration hosted by Read the full story [Page 5] ISchneurChabad & FREE. of Nues. JERRY DALIEGE-Sun-Times Med/a Mommy Crafts that double as Bright time ofyear charitable giving [Page 34] Niles Herald-Spectator 1(c) 2012 Sun-Times Media IAli Rights Reserved STAY CONNECTED TO YOUR COÑÑUNITY! II fl II II OC-frTLOg lI S31CN II II U II ii li u lu Il ii ii ii ui i. isNOI>1Jüt 11111111'a lul(UIll u.'. 11111111 ogy II II __ __ 8I1I18fld __ SI1IN ISiAè81 Iuuuluuu uluuuuI. a. 'u.. C9CODD8Od S311N IdEO 11111111 11111111a u a, hull -L>iWN.L il :: al uuuluuu. uulluuul- __ OOOooO 5T03 . __ .._ __ 8Y9g __ __ __ __ a. __ a. a... a. a. aa a. I. II II II 6TO-34s-LO1 uhu.. lili.... S9 up lor daily newsletters at WWW.SIGNUP.PIONEERLOCAL.COM LOCK IN 2012 PRICES Fniii room. hitchtu, (St$r bødrnùm 'ind rnt pi rennvaUoi desifl WKI b Award-Winning Custom Additions As Chicagoland's remodeling leader, we create stunning home additions that surpass expectations. With over 14,000 projects designed and built, chances are your neighbors have worked with us. From second-story expansions to award- winning kitchens and everything in between, we stand behind every project with our unmatched 15-year structural and 10-year installation warranty. -

Queen Elizabeth

The British monarchy on screen oving images of the British monarchy, in fact and fiction, are almost as M old as the moving image itself, dating back to an 1895 dramatic vignette, The Execution of Mary Queen of Scots. Led by Queen Victoria, British monarchs themselves appeared in the new ‘animated photography’ from 1896. Half a The British century later, the 1953 coronation of Elizabeth II was a milestone in the adoption of television, watched by 20 million Britons and 100 million North Americans. At the century’s end, Princess Diana’s funeral was viewed by 2.5 billion worldwide. monarchy Historians have argued that the power of the image has bolstered the British monarchy as its political power has waned, but media scholars have been slow to examine how that power has been secured by royal self-promotion, entrepreneurial on screen deference, narrative sympathy, reportorial discretion and spectacular exhibition. In the first book-length examination of film and television representations of this enduring institution, distinguished scholars of media and political history analyse the screen representations of royalty from Henry VIII to ‘William and Kate’. Among their concerns are the commercial value of royal representations, the convergence of the monarch and the movie star, and the historical use of the moving image to maintain the Crown’s legitimacy. Seventeen essays by international commentators examine the portrayal of royalty in the ‘actuality’ picture, the early extended feature, amateur cinema, Edited by Mandy Merck the movie melodrama, the Commonwealth documentary, New Queer Cinema, TV current affairs, the big screen ceremonial and the post-historical boxed set. -

Kinderlähmung / Polio (Poliomyelitis) Im Film: Eine Filmographie 2020-07-26

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Hans Jürgen Wulff Kinderlähmung / Polio (Poliomyelitis) im Film: Eine Filmographie 2020-07-26 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14140 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Buch / book Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Wulff, Hans Jürgen: Kinderlähmung / Polio (Poliomyelitis) im Film: Eine Filmographie. Westerkappeln: DerWulff.de 2020-07-26 (Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 196). DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14140. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0196_20.pdf Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Medienwissenschaft: Berichte und Papiere 196, 2020: Polio im Film. Redaktion und Copyright dieser Ausgabe: Hans J. Wulff u. Ludger Kaczmarek. ISSN 2366-6404. URL: http://berichte.derwulff.de/0196_20.pdf. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Letzte Änderung: 26.07.2020. Kinderlähmung / Polio (Poliomyelitis) im Film: Eine Filmographie Kompiliert von Hans J. Wulff Bis in die 1960er war die Poliomyelitis (meist kurz: Polio; dt.: Kinderlähmung) eine !irus-Krank" heit# die au$ der ganzen %elt immer wieder e&idemisch au(rat ) mit *ausenden +on ,rkrankten# -underten +on *oten und zahllosen .&$ern# die k/rperli'he 0'häden da+ontrugen. Bei der soge" nannten 1&aralytischen Poliomyelitis“ 3lei3en lei'hte# in einem !iertel der 4älle schwere 0'hädi" gungen zurü'k: 3lei3ende 6ähmungen# 7elenk$ehlstellungen# Bein" und 8rmlängendifferenzen# %irbelsäulen+erschie3ungen sowie .steo&orose (Kno'henschwund . -

The Pendleton Family of Hyde Park, New York

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF the M adison F amily Descendants 2013 Newsletter A Hudson River School: The Pendleton Family Of Hyde Park, New York “The tour I lately made with Mr. Jefferson of which I have given the outline to my brother was a very agreeable one, and carried us thro’ an interesting Country new to us both.” James Madison, Jr. to James Madison, Sr., July 2d, 1791 View of the Hudson River today looking west from above The Frederick Vanderbilt Estate, Dutchess County, New York. (Photograph by Katy Silberger) By Frederick Madison Smith, NSMFD President 1784 and, finally, with Jefferson in 1791. One of the chief attractions of the Hudson area to President Although President Madison’s extensive trip through the Madison – and to many of his generation – was the prospect of Hudson River Valley with Thomas Jefferson in the Spring of 1791 great profits by land speculation in the rich and fertile soils of parts was to take the pair through landscapes in the upper reaches which of the region. His inability to secure greater capital was to prevent were indeed “new to us both,” this was not Madison’s first venture the making of any great profits here, but a modest investment in up the Hudson but, in fact, his third. Mohawk Valley lands branching west from the Hudson in the His first, as a young man of in 1774, was taken largely by 1780s was to double during the decade he held it. boat and some of the weather encountered on his way was to try Not long after the end of the 1791 trip with Jefferson, James his notoriously delicate health and “nervous disposition” (if not his Madison, Jr. -

Freedom DJANGO UNCHAINED

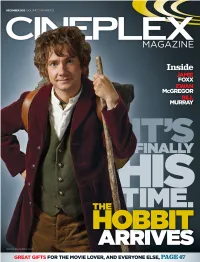

Contents december 2012 | VOL 13 | Nº12 CoVer storY 40 Hobbit’s JourneY it’s been nearly a decade since The Lord of the Rings ended its box-office reign. are we ready for its prequel, The Hobbit? you bet! We trace the project from its shaky early days to this month’s massive release by iNgrid raNdOja reGuLars 6 EditOr’s NOte 8 Snaps 10 In brief 14 SpOtLight 16 All dressed Up 18 In theatres Holiday 56 CastiNg caLL Gift 58 RetUrN eNgagemeNt 60 At hOme Guide, 62 FiNaLLy... Page 47 features 24 fierY foxx 28 Mr. HYde 35 CotiLLard 36 iMpossibLe task Django Unchained star Hyde Park on Hudson star opens up how do you keep a film about Jamie Foxx on why he thinks Bill Murray talks about Rust and Bone’s very private a real-life disaster from being director Quentin tarantino his minimalist approach star Marion Cotillard reveals exploitive? The Impossible’s is the right man to make a to playing U.s. president why she’s so reluctant to Ewan McGregor says it movie about slavery franklin delano roosevelt reveal much of anything isn’t easy by LiaNNe macdOUgaLL by ColiN Covert by mathieU chaNtelois by marNi Weisz 4 | CINEPLEX MAGAZINE | DECEMBER 2012 EDITOR’S NOTE PUBLISHER SALAH BACHIR EDITOR MARNI WEISZ DEPUTY EDITOR INGRID RANDOJA ART DIRECTOR TREVOR STEWART ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR STEVIE SHIPMAN ExecutivE Director, PRODUCTION SHEILA GREGORY CONTRIBUTORS MATHIEU CHANTELOIS, COLIN COVERT, LIANNE MACDOUGALL ADvERTISING SALES FOR CINEPLEX MAGAZINE AND LE MAGAZINE CINEPLEX IS HANDLED BY CINEPLEx MEDIA. HEAD OFFICE 416.539.8800 SENIOR vICE PRESIDENT, SALES LORI LEGAULT (EXT.