A Critical Evaluation of Judicial Selection Reform Efforts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tongass National Forest

S. Hrg. 101-30, Pt. 3 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL PARKS AND FORESTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 987 *&< TO AMEND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT, TO DESIGNATE CERTAIN LANDS IN THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST AS WILDERNESS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES FEBRUARY 26, 1990 ,*ly, Kposrretr PART 3 mm uwrSwWP Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources Boston P«*5!!c y^rary Boston, MA 116 S. Hrg. 101-30, Pr. 3 TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS, NATIONAL PAEKS AND FORESTS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIRST CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON H.R. 987 TO AMEND THE ALASKA NATIONAL INTEREST LANDS CONSERVATION ACT, TO DESIGNATE CERTAIN LANDS IN THE TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST AS WILDERNESS, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES FEBRUARY 26, 1990 PART 3 Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 29-591 WASHINGTON : 1990 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office. Washington, DC 20402 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND NATURAL RESOURCES J. BENNETT JOHNSTON, Louisiana, Chairman DALE BUMPERS, Arkansas JAMES A. McCLURE, Idaho WENDELL H. FORD, Kentucky MARK O. HATFIELD, Oregon HOWARD M. METZENBAUM, Ohio PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico BILL BRADLEY, New Jersey MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico FRANK H. MURKOWSKI, Alaska TIMOTHY E. WIRTH, Colorado DON NICKLES, Oklahoma KENT CONRAD, North Dakota CONRAD BURNS, Montana HOWELL T. -

The Psychological Perspective in Legal Education

Volume 84 Issue 1 Article 7 October 1981 All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers: The Psychological Perspective in Legal Education James R. Elkins West Virginia University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal Profession Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation James R. Elkins, All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers: The Psychological Perspective in Legal Education, 84 W. Va. L. Rev. (1981). Available at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvlr/vol84/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the WVU College of Law at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Law Review by an authorized editor of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elkins: All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers: The Psychological Perspect "ALL MY FRIENDS ARE BECOMING STRANGERS": THE PSYCHOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE IN LEGAL EDUCATIONt JAMES R. ELKINS* PREFACE That I adopted as part of the title for this article "All My Friends Are Becoming Strangers"' suggests the need for expla- nation-what humanistic sociologists call a reflexive statement. More simply put, this article needs a preface. The psychiatrist, Robert Coles, has suggested that a preface permits an author to tell where he stands, and unquestionably in so doing he runs the risk of self-centeredness if not self-display .... We owe it to ourselves and our readers to show something of our lives and our purposes, to indicate, as it were, the context out of which a particular book has emerged.2 This article began as an angry and polemical response to an article by William Simon calling into question what he called The Psychological Vision in legal education.' Upon first reading the Simon article I was dismayed that anyone could be so bold and presumptuous as to attack the psychological perspective and its role in legal education. -

Fibernet Channel Lineup

FIBERNET CHANNEL LINEUP VALUE TIER 2069 HGTV 3026 NickToons LATINO TIER 1001 PBS WETP – Knoxville 2070 Food Network 3027 Boomerang 5000 Sorpresa! 1002 PBS Kids 2071 National Geography 3040 Science Channel 5001 ESPN Deportes 1003 PBS Create 2072 History Channel 3041 Destination America 5002 Cine Mexicano 1004 FiberNET 4 2073 Discovery Channel 3042 Nat Geo Wild 5003 CNN En Espanol 1005 WAGV – Harlan, KY 2074 TLC 3043 diy Network 5004 FOX Deportes 1006 ABC WATE – Knoxville 2075 Animal Planet 3044 Smithsonian 5005 Discovery En Espanol 1007 Morristown TV Today 2076 Investigation Discovery 3045 RFD TV 5006 Discovery Familia 1008 CBS WVLT – Knoxville 2077 Travel Channel 3046 FYI 5007 Enlace 1009 WVLT2 - My East TN TV 2078 E! 3047 Vice 5008 Telemundo 1010 NBC WBIR – Knoxville 2079 Paramount Network 3050 Crimes & Investigations 5009 Universo 1011 FOX WTNZ – Knoxville 2080 Comedy Central 3052 Comedy.TV 1012 CW WBXX – Knoxville 2081 GSN (Game Show Network) 3053 Recipe.TV PREMIUM CHANNELS 1013 ION WPXK – Knoxville 2082 OWN 3054 Cars.TV 6000 HBO 1014 WKNX - Knoxville 2083 TV Land 3055 Pets.TV 6001 HBO 2 1015 WVLR – Tazewell 2084 News Nation 3056 My Destination.TV 6002 HBO Signature 1016 MeTV 2085 WeTV 3057 ES.TV 6003 HBO Family 1017 INSP 2086 truTV 3058 Military History 6004 HBO Latino 1018 Weather Channel 2087 Lifetime 3060 Fido TV 6005 HBO Comedy 1020 ReTV 2088 Freeform 3061 American Heroes Channel 6006 HBO Zone 1028 HSN 2089 Hallmark 3062 Cooking Channel 6007 HBO (West) 1029 HSN 2 2090 Hallmark Movies 3063 Discovery Life 6008 HBO 2 (West) 1030 -

Nuconnect Channel Lineup

NUconnect Channel Lineup June, 2020 TIER 1 (24 CHANNELS) 2067 FX 1001 PBS WETP – Knoxville 2068 FXX 1002 PBS Create * 2069 HGTV 1003 PBS World * 2070 Food Network 1005 WAGV – Harlan, KY * 2071 National Geographic 1006 ABC WATE – Knoxville 2072 History Channel 1008 CBS WVLT – Knoxville 2073 Discovery Channel 1009 WVLT2 - My East TN TV 2074 TLC 1010 NBC WBIR – Knoxville 2075 Animal Planet 1011 FOX WTNZ – Knoxville 2076 Investigation Discovery 1012 CW WBXX – Knoxville 2077 Travel Channel 1013 ION WPXK – Knoxville 2078 E! 1014 WKNX - Knoxville 2079 Paramount Network 1015 WVLR – Tazwell 2080 Comedy Central 1016 MeTV * 2081 GSN (Game Show Network) 1017 INSP 2082 OWN 1018 Weather Channel 2083 TV Land 1020 ReTV 2084 WGN America 1028 HSN 2085 WeTV 1029 HSN 2 2086 truTV 1030 C-SPAN 2087 Lifetime 1031 C-SPAN 2 2088 Freeform 1032 C-SPAN 3 2089 Hallmark 1040 QVC 2090 Hallmark Movies 1041 QVC 2 2091 AMC TIER 2 (78 CHANNELS) 2092 TCM 2000 ESPN 2093 Sundance TV 2001 ESPN 2 2094 IFC 2002 SEC Network 2095 Justice Central 2003 SEC Network (Alternate) 2110 Get TV * 2004 ESPN Classic * 2111 Grit TV * 2005 FOX Sports Tennessee 2112 Bounce * 2006 FOX Sports Southeast 2113 Justice Network * 2007 FOX Sports 1 2114 Laff TV * 2008 NBC Sports Network 2115 Quest 2009 Golf Channel 2116 Cozi 2010 MLB Network 2120 TBN 2020 FOX News 2121 Cowboy Channel 2021 FOX Business 2122 JUCE * 2022 CNN 2123 3ABN 2023 HLN (Headline News) 2124 Daystar Television 2024 MSNBC 2125 The Hillsong Channel * 2025 CNBC 2127 BYU Television 2026 BBC America 2128 Son Life Broadcasting 2027 BBC World News 2129 EWTN 2040 Disney Channel TIER 3 (102 CHANNELS) 2041 Nickelodeon 3000 ESPN U 2042 Cartoon Network 3001 ESPNews 2050 MTV 3002 NFL Network 2051 VH-1 3004 Velocity 2052 CMT 3005 FOX Sports 2 2053 BET 2060 TNT 3006 Big Ten Network 2061 A & E 3007 CBS Sports Network 2062 USA 3020 Disney XD 2063 Oxygen 3021 Disney Jr. -

Amazon Fire TV Via Daystar Apple TV Via GEB America & BVOVN the RHEMA Channel Via ROKU RHEMA Praise TV Broadcast Schedule

RHEMA Praise TV Broadcast Schedule NETWORKS - All Times are Central Networks Listed by Name CITY STATE NETWORK CHANNEL DAY TIME (ZONE) Newark TX BVOVN SAT 9:00 PM SUN Believer’s Voice of 6:30 PM Victory Network FL Please check VARIES VARIES LARGO CTN - CHRISTIAN by city/station TELEVISION (see below) NETWORK TX SAT DALLAS DAYSTAR 8:00 PM MON NETWORK 10:00 PM (Direct TV) 369 (DISH) 263 (AT&T U-verse) 563 (Glorystar) 100 Verizon FiOS 293 East London (South FAITH SAT 7:30 PM Africa) (Central Africa Broadcasting Time) Network Faith Africa DSTV (Multichoice 341 Africa) Flow TV Sky Angel 595 MARCO ISLAND FL FAITH FRI 7:00 AM Broadcasting Network Faith USA (DISH) 269 TULSA OK GEB SUN 10:00 PM (Direct TV) 363 TULSA OK KOTV (CBS) 6 SAT 5:30 AM SUN 5:30 AM OKLAHOMA CITY OK KWTV 9 SUN 4:30 AM FRI 2:00 AM OKLAHOMA CITY OK KSBI (MyTV) 9 SUN 4:30 AM FRI 2:00 AM NAPLES FL SKY ANGEL SUN 8:00 AM SAT (DISH) 262 9:00 PM WED 9:30 PM IL SUN MARION TCT - TRISTATE 6:00 PM CHRISTIAN TV (Direct TV) 377 AR 25 TUES LITTLE ROCK VTN (KVTN) 8:00 PM VICTORY CHRISTIAN NETWORK You may also check by NETWORK below for local stations and air times. RHEMA Praise is also viewable here: (and via many of our broadcasters’ on-demand and live stream sources) Amazon Fire TV via Daystar Apple TV via GEB America & BVOVN The RHEMA Channel via ROKU STATIONS - All Times are Central Local Station Listings by State, (City) CITY STATE CALL LETTERS CHANNEL DAY TIME NETWORK BIRMINGHAM ALABAMA WBUN 27 SUN 8:00 PM DAYSTAR PHOENIX ARIZONA KDTP SAT 7:00 PM DAYSTAR (DISH) 8333 TUCSON KPCE SAT -

All Full-Power Television Stations by Dma, Indicating Those Terminating Analog Service Before Or on February 17, 2009

ALL FULL-POWER TELEVISION STATIONS BY DMA, INDICATING THOSE TERMINATING ANALOG SERVICE BEFORE OR ON FEBRUARY 17, 2009. (As of 2/20/09) NITE HARD NITE LITE SHIP PRE ON DMA CITY ST NETWORK CALLSIGN LITE PLUS WVR 2/17 2/17 LICENSEE ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX NBC KRBC-TV MISSION BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX CBS KTAB-TV NEXSTAR BROADCASTING, INC. ABILENE-SWEETWATER ABILENE TX FOX KXVA X SAGE BROADCASTING CORPORATION ABILENE-SWEETWATER SNYDER TX N/A KPCB X PRIME TIME CHRISTIAN BROADCASTING, INC ABILENE-SWEETWATER SWEETWATER TX ABC/CW (DIGITALKTXS-TV ONLY) BLUESTONE LICENSE HOLDINGS INC. ALBANY ALBANY GA NBC WALB WALB LICENSE SUBSIDIARY, LLC ALBANY ALBANY GA FOX WFXL BARRINGTON ALBANY LICENSE LLC ALBANY CORDELE GA IND WSST-TV SUNBELT-SOUTH TELECOMMUNICATIONS LTD ALBANY DAWSON GA PBS WACS-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY PELHAM GA PBS WABW-TV X GEORGIA PUBLIC TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION ALBANY VALDOSTA GA CBS WSWG X GRAY TELEVISION LICENSEE, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ADAMS MA ABC WCDC-TV YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY NBC WNYT WNYT-TV, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY ABC WTEN YOUNG BROADCASTING OF ALBANY, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY ALBANY NY FOX WXXA-TV NEWPORT TELEVISION LICENSE LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY AMSTERDAM NY N/A WYPX PAXSON ALBANY LICENSE, INC. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY PITTSFIELD MA MYTV WNYA VENTURE TECHNOLOGIES GROUP, LLC ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CW WCWN FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY PBS WMHT WMHT EDUCATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY SCHENECTADY NY CBS WRGB FREEDOM BROADCASTING OF NEW YORK LICENSEE, L.L.C. -

Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move Call

TV Broadcasters’ Impact on Virginia Impact on VA 09 Broadcasters have an impact of $31.87 billion annually on Virginia’s economy. 65,610 Jobs 27 Commercial TV Stations Call Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move WFMY-TV 2 CBS Greensboro-High Point-Winston Salem, NC (46) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WGHP 8 FOX Greensboro-High Point-Winston Salem, NC (46) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WGPX-TV 16 ION Media Networks Greensboro-High Point-Winston Salem, NC (46) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WMYV 48 My Network TV Greensboro-High Point-Winston Salem, NC (46) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WUNL-TV 26 Public Television Greensboro-High Point-Winston Salem, NC (46) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WXII-TV 12 NBC Greensboro-High Point-Winston Salem, NC (46) Phase 9: Mar 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WBXX-TV 20 CW Television Network Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WETP-TV 2 Public Television Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WKOP-TV 15 Public Television Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WPXK-TV 54 ION Media Networks Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WTNZ 43 FOX Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WVLR 48 Christian Television Network Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 7: Oct 19, 2019 - Jan 17, 2020 WVLT-TV 8 CBS Knoxville, TN (62) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WDBJ 7 CBS Roanoke-Lynchburg, VA (67) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WFXR 27 FOX Roanoke-Lynchburg, VA (67) Phase 5: Aug 3, 2019 - Sept 6, 2019 WLHG-CD 0 Religious -

Cable Television Channel Lineup October 2014

Cable Television Channel Lineup October 2014 Channel Lineup by Number 23-1 WKOP - PBS 34-2 FXX 42-2 ABC Family 50-2 Hallmark Channel 23-2 WPXK - ION 34-3 Golf Channel 42-3 The Disney Channel 50-3 OWN 24-1 HSN 35-1 Fox Sports 1 43-1 Nickelodeon 51-1 CSPAN3 24-2 WKNX - IND 35-2 SportSouth 43-2 Cartoon Network 51-2 Galavision 25-1 WVLT - CBS 35-3 MLB Network 43-3 TV Land 51-3 Univision 25-2 WBIR - NBC 36-1 NBC Sports Network 44-1 AMC 53-1 WVLR 26-1 WTNZ - FOX 36-2 SEC 44-2 Turner Classic Movies 53-2 10News2 26-2 WBXX - CW 36-3 SEC Extra 44-3 BET 53-3 WVLT-DT2 - MyTV 27-1 WATE - ABC 37-1 Velocity 45-1 Oxygen 53-4 WAGV - IND 27-2 QVC 37-2 The Weather Channel 45-2 Bravo 53-5 WATE 2 - Live Well 28-1 Jewelry Television 37-3 CNBC 45-3 SyFy 53-6 WBIR 2 - MeTV 28-2 WGN America 38-1 MSNBC 46-1 Spike TV 53-7 WTNZ-DT2 - This TV 29-1 CSPAN 38-2 CNN 46-2 Comedy Central 54-1 WKOP - PBS Create 29-2 TBN 38-3 HLN 46-3 MTV 54-2 WKOP - PBS World 31-1 E! 39-1 FOX News Channel 47-1 VH-1 54-3 Educational Access 31-2 Lifetime 39-2 History 47-2 CMT (CH 5) 31-3 TLC 39-3 TruTV 47-3 MTV2 54-4 Leased Access 32-1 TBS 40-1 A&E 48-1 TV Guide (BB 98) 32-2 TNT 40-2 Discovery Channel 48-2 GSN 54-5 Local Origination 32-3 USA 40-3 National Geographic 48-3 Investigation Discovery (Aloca 3) 33-1 fx 41-1 Travel Channel 49-1 Disney XD 54-6 Local Origination 33-2 ESPN 41-2 Food Network 49-2 CSPAN2 (Community Info) 33-3 ESPN2 41-3 HGTV 49-3 Fox Business Network 54-7 Government Access 34-1 FS South 42-1 Animal Planet 50-1 ShopHQ (TSL) Channel Lineup by Name 53-2 10News2 39-1 FOX -

Reviewing the 2010S in Farragut — Yet Looking Ahead

PRSRT STD US POSTAGE PAID KNOXVILLE TN PERMIT # 109 farragutpress.com • @farragutpress • @farragutpress1 • © 2019 farragutpress all rights reserved • 50¢ ISSUE 17 VOLUME 32 FARRAGUT, TENNESSEE THURSDAY, JANUARY 2, 2020 • 1A 2nd Millennial decade Reviewing the 2010s in Farragut — yet looking ahead ur just-completed decade featured a super-rare total eclipse, an introduction to red-light cameras, a special missing monument suddenly found years later, OTown term-limits, a really big Costco sales tax boost, a $1.1 million Town debt coming out of seemingly nowhere, a no-quit football state champ and the heartbreak of high school suicides. And so much more. Here’s a rundown of January 2010 through December 2018 as reported in farragutpress. (See 2019 highlighted in our Dec. 26 issue) STAFF REPORTS ■ [email protected] 2010 • Farragut citizens voted in favor of terms limits for (Left) Family witnessing 2017 total eclipse. (Right) Admiral Farragut’s Monument turned up after five years. its Board of Mayor and Aldermen, which limits elected officials to a maximum of 12 years service: two four-year terms, either as mayor or an alderman, and one four-year term, either as mayor or an alderman Visions of a new year, goals to reach by • Red-light cameras were introduced at six Town intersections, with videoed violators given citations, as 2030 from Williams, FMPC chair Holladay numerous citizens voiced their opposition to the cameras • The James David Glasgow Farragut statue was un- TAMMY CHEEK big things we’d like to see.” veiled in Farragut Memorial Plaza ■ [email protected] He added another project he would like to see under • Town businessman David Purvis founded Farragut way is McFee Park. -

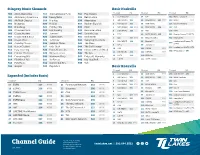

Channel Guide Channels May Be Subject to Twinlakes.Net | 800.644.8582 Change

Stingray Music Channels Basic Nashville 900 Adult Alternative 917 Groove Disco & Funk 934 Pop Classics Channel HD Channel HD Channel HD 901 Alt-Country Americana 918 Heavy Metal 935 Retro Latino 1 TLTV Weather 14 ION 212 WCTE - CreateTV 902 Alt-Rock Classics 919 Hip Hop 936 Alternative 2 ABC (WKRN) 302 15 NewsNation 293 WTVE 213 QVC 2 WTVE 903 Bluegrass 920 Hit List 937 Rock en Español 3 FOX (WZTV) 303 16 GBN (GSPL) 231 Court TV Mystery 904 Broadway 921 Holiday Hits 938 Rock 4 NBC (WSMV) 304 WTVE 22 PBS (WCTE) 296 287 Grit 905 Chamber Music 922 Hot Country 939 Romance Latino 5 CBS (WTVF) 305 29 TBN 299 COZI 906 Classic Masters 923 Jammin’ 940 Smooth Jazz 6 TLTV 30 MYTV (WUXP) 330 951 Overton County TV (OCTV) 907 Classic RnB & Soul 924 Jazz Masters 941 Soul Storm 7 QVC 307 WTVE 50 News Channel 5+ 952 New Life TV Classic Rock Jazz Now Swinging Standards 908 925 942 8 PBS (WNPT) 308 60 Bounce TV Cumberland Plateau TV 953 909 Country Classics 926 Jukebox Oldies 943 The Blues (CPTV) 9 NPT-2 99 Jewelry TV 910 Dance Clubbin’ 927 Kids’ Stuff 944 The Chill Lounge 954 Cumberland Life TV (CLTV) 10 HSN 101 CSPAN WTVE 911 Easy Listening 928 Éxitos Tropicales 945 Christian Pop and Rock 996 PPV Event TV 997 11 CW (WNAB) 311 102 CSPAN 2 WTVE 912 Eclectic Electronic 929 Ritmos Latinos 946 The Spa 913 Everything 80’s 930 Maximum Party 947 Exitos del Momento 12 MeTV 312 210 PBS Kids 914 Flashback 70’s 931 No Fences 948 Hip-Hop/RnB 13 Laff TV 211 WCTE - World 915 Folk Roots 932 Nothin’ But 90’s 949 Y2K 916 Gospel 933 Pop Adult Basic Knoxville Channel HD Channel -

Guest Directory

Kodak/Sevierville 161 West Dumplin Valley Road Kodak, TN 37764 Phone: 865-933-3131 Fax: 865-933-5550 Guest Directory Room Copy – Please Leave for the Next Guest Welcome Welcome to the Comfort Suites, Kodak/Sevierville. It is such a pleasure to have you here. Whether you are spending one night, one week or one month, the Comfort Suites is an excellent choice. This directory is designed to provide you with information concerning our services, facilities and nearby attractions. We hope if is helpful to you during your stay. Your patronage is highly valued and, although we have tried to anticipate your needs, do not hesitate to call us for additional information or assistance. We hope you enjoy your stay and look forward to seeing you again. At the Comfort Suites we are always looking for ways to better take care of you. It has been our pleasure to take care of you. Sincerely, The Staff & Management Kodak/Sevierville 161 West Dumplin Valley Road Kodak, TN 37764 Phone: 865-933-3131 Fax: 865-933-5550 #9487 Guest Information Airlines American Airlines ....................................................................800-433-7300 Continental Airlines .................................................................800-523-3273 Delta Air Lines .........................................................................800-221-1212 Southwest Airlines ...................................................................800-435-9792 United Airlines .........................................................................800-241-6522 US Airways ..............................................................................800-428-4322 Airports McGhee Tyson Airport .............................................................865-342-3000 2055 Alcoa Highway, Alcoa, TN 37701 Gatlinburg Pigeon Forge Airport ..............................................865-453-8393 (Private aircraft, no commercial flights) 134 Air Museum Way, Sevierville, TN 37862 Baby Cribs: Baby cribs are complimentary to our guests. Please inquire at the • GuestWelcome Information Front Desk by dialing 0. -

Channel Guide

Music Choice Basic Nashville Select Music Choice Channels are available on Watch TV Everywhere. Channel HD Channel HD Channel HD 900 Hit List 917 Classic Rock 934 Contemporary Christian 1 TLTV Weather 14 ION 212 WCTE - CreateTV 901 Max 918 Soft Rock 935 Pop Latino 2 ABC (WKRN) 302 15 WGN America 293 WTVE 213 QVC 2 WTVE 902 Dance/EDM 919 Love Songs 936 Musica Urbana 3 FOX (WZTV) 303 16 GBN (GSPL) 231 Escape TV 903 MC Indie (TV-MA) 920 Pop Hits 937 Mexicana 4 NBC (WSMV) 304 WTVE 22 PBS (WCTE) 296 287 Grit 904 Hip-Hop and R&B 921 Party Favorites 938 Tropicales 5 CBS (WTVF) 305 29 TBN 299 COZI 905 Rap 922 Teen Beats 939 Romances 6 TLTV 30 MYTV (WUXP) 330 951 Overton County TV (OCTV) 906 Hip-Hop Classics 923 Kidz Only 940 Sounds of the Seasons 7 QVC 307 WTVE 50 News Channel 5+ 952 New Life TV 907 Throwback Jamz 924 Toddler Tunes 941 Stage & Screen 8 PBS (WNPT) 308 60 Bounce TV Cumberland Plateau TV 953 908 R&B Classics 925 Y2K 942 Soundscapes (CPTV) 9 NPT-2 99 Jewelry TV 909 R&B Soul 926 90’s 943 Smooth Jazz 954 Cumberland Life TV (CLTV) 10 HSN 101 CSPAN WTVE 910 Gospel 927 80’s 944 Jazz 955 Eagle Cam (Seasonal) 11 CW (WNAB) 311 102 CSPAN 2 WTVE 911 Reggae 928 70’s 945 Blues PPV Event TV MeTV PBS Kids 996 997 912 Rock 929 Solid Gold Oldies 946 Singers & Swing 12 210 998 Twin Lakes Email 913 Metal 930 Pop & Country 947 Easy Listening 13 Laff TV 211 WCTE - World 914 Alternative 931 Today’s Country 948 Classical Masterpieces 915 Adult Alternative 932 Country Hits 949 Light Classical Basic Knoxville (Fentress County) 916 Rock Hits 933 Classic Country Channel HD Channel HD Channel HD 1 TLTV Weather 16 GBN (GSPL) WTVE 288 Cozi Expanded (Includes Basic) 2 ABC (WATE) 302 22 PBS (WCTE) 296 289 Get TV Select Music Choice Channels are available on Watch TV Everywhere.