Caversham (August 2019) • © VCH Oxfordshire • Economic Hist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appeal Decisions

Appeal Decisions Hearing held on 13 November 2018 Site visits made on 10 & 14 November 2018 by Robert Parker BSc (Hons) Dip TP MRTPI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Decision date: 17 December 2018 Appeal A Ref: APP/Q3115/W/18/3198315 Land on West side of Tokers Green Lane (aka The Elms), Tokers Green Lane, Tokers Green RG4 9EB The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant planning permission. The appeal is made by Perfectfield Limited against the decision of South Oxfordshire District Council. The application Ref P17/S2021/FUL, dated 30 May 2017, was refused by notice dated 18 October 2017. The development proposed is erection of 4 number four bedroom; 4 number three bedroom, and 2 number two bedroom houses and associated development including revised access, and provision of public footpath and retention and improvement of a wildlife area. Appeal B Ref: APP/Q3115/W/18/3198316 Land to the west of Tokers Green Lane (also known as ‘The Elms’), Tokers Green Lane, Tokers Green RG4 9EB The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant planning permission. The appeal is made by Perfectfield Limited against the decision of South Oxfordshire District Council. The application Ref P17/S2003/FUL, dated 30 May 2017, was refused by notice dated 18 October 2017. The development proposed is erection of: (i) Market housing: 4 number four bedroom; 4 number three bedroom and 1 number two bedroom houses; (ii) Affordable housing: 4 number three Richboroughbedroom and 1 number two bedroom Estates houses; (iii) associated development including revised access, and provision of public footpath, and (iv) retention and improvement of a wildlife area. -

2-25 May 2015 Artists’ Open Studios & Exhibitions Across Oxfordshire

OXFORDSHIRE ARTWEEKS OXFORDSHIRE ARTWEEKS 2-25 MAY 2015 FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE 2015 FREE FESTIVAL ARTISTS’ OPEN STUDIOS & EXHIBITIONS ACROSS OXFORDSHIRE FREE FESTIVAL GUIDE www.artweeks.org INCLUDES CHRISTMAS EXHIBITIONS Supported by OLA offers small class sizes, outstanding pastoral care and a wide range of academic and extra-curricular activities, ensuring our pupils are confident, engaged and excited about their next steps in life. For further information, call 01235 523147 (Junior School) or 01235 524658 (Senior School), or visit www.olab.org.uk R a d l e y R o a d · A b i n g d o n - o n - T h a m e s · O x f o r d s h i r e · O X 1 4 3 P S Artweeks IFC 2015.indd 1 11/20/2014 2:54:23 PM Carefully delivered to Oxfordshire’s finest homes and venues Carefully deliveredfinest homes to Oxfordshire’s and venues OCTOBER 2014 OXOCTOBERCarefully 2014 delivered to Oxfordshire’s finest homes and venues OXOXOCTOBER 2014 Each monthOX OX magazine brings the Oxfordshire art your complimentary copy your complimentary copy your complimentary copy scene to an audience that delights in Oxfordshire art E EDITS Artweeks E EDITS Artweeks E EDITS Artweeks Artweeks EDITS E the building has sprung back to life with magical OXFORDSHIRE ARTWEEKS characters to whisk you away into the imaginative CHRISTMAS EXHIBITIONS stories of your childhood 11-6pm 22nd-23rd November at dozens of venues across the county As Christmas comes closer, we’re all on the hunt for that unusual and unique Christmas gift, and to help you out, across the county, artists and designer-makers who are normally hidden from view (and quite possibly hibernate in the deepest snows between the summer Oxfordshire Artweeks festivals) are braving the wintry winds and hosting festive exhibitions and shows for one weekend only. -

Peppard Ward Independent News

Peppard Ward Independent News Putting People First! Why Independent? Cllr Mark Ralph responds: “When I was first asked to stand for election as a Conservative Councillor in 2004, I did so on the basis that I would not compromise my personal principles.” “Jamie Chowdhary’s deselection and the subsequent vendetta against him by those within Reading East Conservative Association was a disgrace. In-fighting and internal politics were already impeding Conservative Councillors’ ability to serve their residents and the behaviour of the Association’s leadership towards Jamie was such that it was no longer an organisation that I wished to belong to.” Other Conservative Councillors left the Association too but have since crept back, no doubt hoping that no one will notice! Mark says: “As a Ward Councillor, I have always followed the principle of ‘People First, Politics Second’ and in addition to people’s day to day concerns, I am now freer to focus on those things that my residents tell me matter most: quality services, safer communities, support for older residents and vulnerable children, protection of the environment, good schools, more school places, and better value for money for the Council Taxpayer.” Thank You! To all those that voted for “Following Jamie’s experience, I fully expect Jamie Chowdhary in the 2012 Cllr Willis and his colleagues within the elections, thank you. Reading East Conservative Association to We were overwhelmed by the conduct a very unpleasant campaign leading number of people that came up to the 2014 elections. forward to support him and on the day, he took just under I hope that people will see this for what it is 800 votes – unprecedented for and judge me on my many achievements for an Independent but, sadly the residents of Peppard Ward.” insufficient for him to retain his position as a Councillor Councillor Mark Ralph T: 0118 948 1615 E: [email protected] Twitter: @Councillor1UK Website: www.PeppardWard.com Promoted by Jamie Chowdhary, on behalf of the Peppard Independents Organisation of, 16c Upton Road, Reading, RG30 4BJ. -

24 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

24 bus time schedule & line map 24 Central Reading - Emmer Green via Caversham View In Website Mode Bridge, Hemdean Road The 24 bus line Central Reading - Emmer Green via Caversham Bridge, Hemdean Road has one route. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Reading Town Centre: 5:10 AM - 11:10 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 24 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 24 bus arriving. Direction: Reading Town Centre 24 bus Time Schedule 40 stops Reading Town Centre Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 8:40 AM - 6:40 PM Monday 5:10 AM - 11:10 PM Friar Street, Reading Town Centre Tuesday 5:10 AM - 11:10 PM Forbury Road, Reading Town Centre 10 Forbury Road, Reading Wednesday 5:10 AM - 11:10 PM Station North Interchange, Reading Thursday 5:10 AM - 11:10 PM Vastern Road, Reading Friday 5:10 AM - 11:10 PM Swansea Road, Caversham Road Saturday 6:00 AM - 11:10 PM 131 Caversham Road, Reading The Moderation, Caversham Road 221 Caversham Road, Reading 24 bus Info Bridge Street Caversham, Caversham Direction: Reading Town Centre Stops: 40 Church Street, Caversham Trip Duration: 44 min Church Street, Reading Line Summary: Friar Street, Reading Town Centre, Forbury Road, Reading Town Centre, Station North Caversham Library, Caversham Interchange, Reading, Swansea Road, Caversham Road, The Moderation, Caversham Road, Bridge Hemdean Hill, Caversham Street Caversham, Caversham, Church Street, Caversham, Caversham Library, Caversham, Queen Street, Caversham Hemdean Hill, Caversham, Queen Street, Caversham, Victoria Road, -

THE RIVER THAMES a Complete Guide to Boating Holidays on the UK’S Most Famous River the River Thames a COMPLETE GUIDE

THE RIVER THAMES A complete guide to boating holidays on the UK’s most famous river The River Thames A COMPLETE GUIDE And there’s even more! Over 70 pages of inspiration There’s so much to see and do on the Thames, we simply can’t fit everything in to one guide. 6 - 7 Benson or Chertsey? WINING AND DINING So, to discover even more and Which base to choose 56 - 59 Eating out to find further details about the 60 Gastropubs sights and attractions already SO MUCH TO SEE AND DISCOVER 61 - 63 Fine dining featured here, visit us at 8 - 11 Oxford leboat.co.uk/thames 12 - 15 Windsor & Eton THE PRACTICALITIES OF BOATING 16 - 19 Houses & gardens 64 - 65 Our boats 20 - 21 Cliveden 66 - 67 Mooring and marinas 22 - 23 Hampton Court 68 - 69 Locks 24 - 27 Small towns and villages 70 - 71 Our illustrated map – plan your trip 28 - 29 The Runnymede memorials 72 Fuel, water and waste 30 - 33 London 73 Rules and boating etiquette 74 River conditions SOMETHING FOR EVERY INTEREST 34 - 35 Did you know? 36 - 41 Family fun 42 - 43 Birdlife 44 - 45 Parks 46 - 47 Shopping Where memories are made… 48 - 49 Horse racing & horse riding With over 40 years of experience, Le Boat prides itself on the range and 50 - 51 Fishing quality of our boats and the service we provide – it’s what sets us apart The Thames at your fingertips 52 - 53 Golf from the rest and ensures you enjoy a comfortable and hassle free Download our app to explore the 54 - 55 Something for him break. -

READING BOROUGH COUNCIL LGBCE WARD BOUNDARY REVIEW 2019 Ward No. of Cllrs Electorate 2025 Variance % Comprised Electorate Explan

READING BOROUGH COUNCIL LGBCE WARD BOUNDARY REVIEW 2019 Ward No. of Electorate Variance Comprised Electorate Explanation Cllrs 2025 % A The Heights 3 7,626 1 Mapledurham Y 2,512 New 3-member ward covering west Caversham Thames W 1,153 Communities: Thames WA 3,473 Caversham Heights Mapledurham PLUS 488 Hemdean Valley (both sides) NW part of Peppard V New development – limited This is a new ward, merging the single-member Mapledurham ward in the west of Caversham with Thames ward. It is an area of private and mostly up-market housing, running north from the Thames into the foothills of the Chilterns along the Woodcote Road, Kidmore Road and Hemdean Road. Mapledurham ward comprises, in the south, Caversham Heights; and to the north that part of Mapledurham parish which transferred to Reading Borough from Oxfordshire in 1977. Mapledurham village is still in South Oxfordshire, some miles away. The Working Party has proposed moving Thames WB into ward C, to achieve electoral equality. This area had previously been in Caversham ward, and was moved into Thames by the 2001/02 review. The Working Party has also proposed transferring the NW part of Peppard V into ward A. These are the roads in a triangle formed by Surley Row, St Barnabas Road and Evesham Road, and Rotherfield Way, to east of Highdown School and on the eastern side of the Hemdean valley.. [NB – total does not include west (odd) side of Evesham Road – nos. 19-57 – a further 44 electors live here] READING BOROUGH COUNCIL LGBCE WARD BOUNDARY REVIEW 2019 Ward No. -

Display PDF in Separate

Efl' lv^<*cr\2 S 8 o x 6 West Area’s Millennium Festival Celebration Wildlife Encounter 2000 at View Island, Reading Liz O’Neill, Partnerships Officer West Area, Thames Region Foreword It was in October 1999, when I first heard of the Agency's concept of Millennium Festivals (that seems a very long time ago!). The concept was a spectacular one - to celebrate the millennium by leaving a legacy and working with local communities - but to put it into practice was going to be a challenge. The project team, who worked on West Area's Millennium Festival at View Island, came from all different functions of the Agency and for most it was the first time they had carried out project work of this nature and worked in a truly multifunctional team. During the course of the project there were many problems, but the team overcame these hurdles by working together, being innovative and having what can only be described as dog-eared determination! The physical improvements to the island and the two-day event went well and we received very positive feedback from members of the public. The staff involved enjoyed working on the project and also got a sense of purpose and pride in what they had achieved or been a part of. These feelings raised morale long after the event. I feel very privileged to have managed West Area's Festival, which left such a wonderful legacy in View Island. I am proud of the project team who worked really hard to pull it all together and the additional people who helped on the two days. -

THE RIVER THAMES by HENRY W TAUNT, 1873

14/09/2020 'Thames 1873 Taunt'- WHERE THAMES SMOOTH WATERS GLIDE Edited from link THE RIVER THAMES by HENRY W TAUNT, 1873 CONTENTS in this version Upstream from Oxford to Lechlade Downstream from Oxford to Putney Camping Out in a Tent by R.W.S Camping Out in a Boat How to Prepare a Watertight Sheet A Week down the Thames Scene On The Thames, A Sketch, By Greville Fennel Though Henry Taunt entitles his book as from Oxford to London, he includes a description of the Thames above Oxford which is in the centre of the book. I have moved it here. THE THAMES ABOVE OXFORD. BY THE EDITOR. OXFORD TO CRICKLADE NB: going upstream Oxford LEAVING Folly Bridge, winding along the river past the Oxford Gas-works, and passing under the line of the G.W.R., we soon come to Osney Lock (falls ft. 6 in.), close by which was the once-famous Abbey. There is nothing left to attest its former magnificence and arrest our progress, so we soon come to Botley Bridge, over which passes the western road fro Oxford to Cheltenham , Bath , &c.; and a little higher are four streams, the bathing-place of "Tumbling bay" being on the westward one. Keeping straight on, Medley Weir is reached (falls 2 ft.), and then a long stretch of shallow water succeeds, Godstow Lock until we reach Godstow Lock. Godstow Lock (falls 3 ft. 6 in., pay at Medley Weir) has been rebuilt, and the cut above deepened, the weeds and mud banks cleared out, so as to leave th river good and navigable up to King's Weir. -

EBR Walk Prog Jan Apr 2017

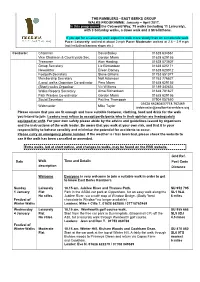

THE RAMBLERS - EAST BERKS GROUP WALKS PROGRAMME: January – April 2017. In this programme: the Cotswold Way; 75 walks (including 11 Leisurely), with 3 Saturday walks, a dawn walk and 2 Strollathons. If you opt for a Leisurely walk expect to walk more slowly than on a moderate walk. Pace: Leisurely: walked at about 2 mph Pace: Moderate: walked at 2.5 – 2.9 mph (not including banana stops etc.) Contacts: Chairman David Bailey 01628 634561 Vice Chairman & Countryside Sec. Gordon Marrs 01628 629155 Treasurer Alan Harding 01628 673607 Group Secretary Liz Richardson 01628 625171 Newsletter Eileen Dorney 01628 620012 Footpath Secretary Steve Gillions 01753 851077 Membership Secretary Neil Adamson 01753 776627 (Long) walks Organiser Co-ordinator Pera Marrs 01628 629155 (Short) walks Organiser Viv Williams 01189 342834 Walks Reports Secretary Alma Richardson 01628 781827 Path Warden Co-ordinator Gordon Marrs 01628 629155 Social Secretary Pauline Thompson 07904 057850 01628 662808/07718 762469 Webmaster Mike Taylor [email protected] Please ensure that you are fit enough and have suitable footwear, clothing, food and drink for the walk you intend to join. Leaders may refuse to accept participants who in their opinion are inadequately equipped or unfit. For your own safety please abide by the advice and guidelines issued by organisers and the instructions of the walk leader. Be aware that you walk at your own risk, and that it is your responsibility to behave sensibly and minimise the potential for accidents to occur. Please carry an emergency phone number. If the weather is / has been bad, please check the website to see if the walk has been cancelled or amended. -

SODC LP2033 2ND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT FINAL.Indd

South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT Appendix 5 Safeguarding Maps 209 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 210 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 211 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 212 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 213 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 214 216 Local Plan2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONSDOCUMENT South Oxfordshire DistrictCouncil South Oxfordshire South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 216 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 217 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 218 Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT South Oxfordshire District Council 219 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS DOCUMENT 220 South Oxfordshire District Council Local Plan 2033 SECOND PREFERRED OPTIONS -

Caversham's Past Landlords What's on 2018

t: 0118 946 1800 e: [email protected] insight w: farmeranddyer.com Spring 2018 Bulletin Caversham’s Past Landlords Recently we have sold two super riverside residences on Heron Island, built by Heron Are you Homes during the mid 1980’s. These three storey properties both had direct Thameside frontages and are often popular with boating enthusiasts Compliant? due to their mooring facilities. But scroll back in time and you can see how old this From 1st April 2018 new regulations known site really is, the Mill at Heron Island is believed to as MEES, the Minimum Energy Efficiency be the one mentioned in the Domesday Book and Standards, for England or Wales mean that in the time of Edward the Confessor it was held residential landlords and letting agents acting on their behalf will not be able to by Svain, a Saxon thane and Lord of Caversham. In grant a tenancy to either new or existing its day, it is thought to have been as attractive as tenants if the property’s EPC score is a low the mill at Mapledurham, with grain for the mill rating of F or G. delivered by barge until 1840. The mill was still in full use in 1910 although by 1929 it had finally From April 1 2020, if there is a tenant closed. already in situ, it will become illegal for residential landlords to continue letting the Following the end of milling, the island had a short property out if the EPC still has the rating lived cork factory situated on it. -

Live Well Oxfordshire Support and Care Guide for Adults 2016/17

Live Well Oxfordshire Support and Care Guide for Adults 2016/17 Thames, Oxford Your guide to support and care services in Oxfordshire • Support at home • Specialist care • Useful contacts • Care homes In association with www.oxfordshire.gov.uk www.carechoices.co.uk PROVIDING PERSON CENTRED CARE IN A HOME FROM HOME ENVIRONMENT. Cheney House is located in the picturesque historical village of Middleton Cheney. The delightful Grade II listed building oozes character and with newly refurbished rooms and living areas offers an idyllic setting for our person centred approach to care. Care can be accommodated on a Long Term: Short term: Respite, Convalescence and Day Care basis. With a strong sense of community, we are driven by our leisure and lifestyle services where promotion of Independence, Dignity and Individuality is a priority. We aim to provide a Person Centred and Resident Led, Happy and Secure Environment where making new and happy memories are a priority. When you visit Cheney House and meet our warm, friendly staff you will find the home from home you and your loved one is looking for. As an established care provider you can be reassured that Regal Care Trading Ltd always strive to provide a high standard of care throughout our 17 homes across the UK. CHENEY HOUSE Rectory Lane Middle Cheney Banbury OX17 2NZ Telephone: 01295 710494 Email: [email protected] For more info please... Call: 0845 8731234 • 30 station road, Orpington, Kent BR6 0SA Email: [email protected] • Web: www.regalcarehomes.com Regal FP 2016.indd