National Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leishmania Major in Tunisia by Microsatellite Analysis

RESEARCH ARTICLE Spatio-temporal Genetic Structuring of Leishmania major in Tunisia by Microsatellite Analysis Myriam Harrabi1,2*, Jihène Bettaieb1, Wissem Ghawar1, Amine Toumi1, Amor Zaâtour1, Rihab Yazidi1, Sana Chaâbane1, Bilel Chalghaf1, Mallorie Hide3, Anne-Laure Bañuls3, Afif Ben Salah1 1 Institut Pasteur, Tunis, Tunisia, 2 Faculté des Sciences de Bizerte-Université de Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia, 3 UMR MIVEGEC (IRD 224-CNRS5290-Universités Montpellier 1 et 2), Centre IRD, Montpellier, France * [email protected] Abstract In Tunisia, cases of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania major are increasing and spreading from the south-west to new areas in the center. To improve the current knowledge on L. major evolution and population dynamics, we performed multi- locus microsatellite typing of human isolates from Tunisian governorates where the disease is endemic (Gafsa, Kairouan and Sidi Bouzid governorates) and collected during two peri- OPEN ACCESS ods: 1991–1992 and 2008–2012. Analysis (F-statistics and Bayesian model-based approach) of the genotyping results of isolates collected in Sidi Bouzid in 1991–1992 and Citation: Harrabi M, Bettaieb J, Ghawar W, Toumi A, – Zaâtour A, Yazidi R, et al. (2015) Spatio-temporal 2008 2012 shows that, over two decades, in the same area, Leishmania parasites evolved Genetic Structuring of Leishmania major in Tunisia by by generating genetically differentiated populations. The genetic patterns of 2008–2012 iso- Microsatellite Analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(8): lates from the three governorates indicate that L. major populations did not spread gradually e0004017. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004017 from the south to the center of Tunisia, according to a geographical gradient, suggesting Editor: Gabriele Schönian, Charité University that human activities might be the source of the disease expansion. -

Tunisia Investment Plan

Republic of Tunisia FOREST INVESTMENT PROGRAM IN TUNISIA 1. Independent Review of the FIP Tunisia 2. Matrix: Responses to comments and remarks of the independent expert November 2016 Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Direction Ressources Hydrauliques et de Générale des la Pêche Forêts 1 CONTENTS _______________________ I. Independent Review of the Forest Investment Plan of Tunisia 3 II. Matrix: Response to comments and remarks of the independent expert 25 2 I. Independent Review of the Forest Investment Plan of Tunisia Reviewer: Marjory-Anne Bromhead Date of review: (first draft review, 18th August 2016) PART I: Setting the context (from the reviewers overall understanding of the FIP document) Tunisia is the first country in North Africa and the Middle East to benefit from FIP support1, and provides an important example of a country where climate change mitigation and climate resilience go hand in hand. Tunisia is largely “forest poor”, with forests concentrated in the high rainfall areas in the north and North West of the country and covering only 5 percent of the territory (definitions vary). However rangelands are more widespread, covering 27 percent of the land area and are also a source of rural livelihoods and carbon sequestration, while both forests and rangelands are key to broader watershed management (Tunisia is water-scarce). Tunisia, together with the North Africa and Middle East region more broadly, is one of the regions most affected by climate change, with higher temperatures, more periods of extreme heat and more erratic rainfall. REDD actions will help to control erosion and conserve soil moisture and fertility, increasing climate resilience, while also reducing the country’s carbon footprint; the two benefits go hand in hand. -

A Study in Dispossession: the Political Ecology of Phosphate in Tunisia

A study in dispossession: the political ecology of phosphate in Tunisia Mathieu Rousselin1 Independent Researcher, Dortmund, Germany Abstract This article seeks to evidence the social, environmental and political repercussions of phosphate extraction and transformation on two peripheral Tunisian cities (Gabes and Gafsa). After positing the difference between class environmentalism and political ecology, it addresses the harmful effects of phosphate transformation on the world's last coastal oasis and on various cities of the Gulf of Gabes. It then sheds light on the gross social, environmental and health inequalities brought about by phosphate extraction in the mining region of Gafsa. The confiscatory practices of the phosphate industry are subsequently linked with global production and distribution chains at the international level as well as with centralized and authoritarian forms of government at the national and local level. Dispossessed local communities have few alternatives other than violent protest movements and emigration towards urban centers of wealth. Using the recent experience in self-government in the Jemna palm grove, the article ends with a reflection on the possible forms of subaltern resistance to transnational extractivism and highlights the ambiguous role of the new "democratic state" as a power structure reproducing patterns of domination and repression inherited from the colonial period and cemented under the dictatorship of Ben Ali. Keywords: political ecology, transnational extractivism, phosphate, Tunisia. Résumé Cet article s'efforce de mettre en évidence les répercussions sociales, environnementales et politiques de l'industrie d'extraction et de transformation du phosphate sur deux villes de la périphérie tunisienne (Gabès et Gafsa). Après avoir exposé la différence entre l'environnementalisme de classe et l'écologie politique, cet article analyse les effets délétères de la transformation du phosphate sur la dernière oasis littorale du monde ainsi que sur plusieurs villes du Golfe de Gabès. -

Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region In

Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in Republic Project Republic of Tunisia Ministry of Development, Investment, and International Cooperation (MDICI), South Development Office (ODS) Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia Final Report Part 1 Current Status of Tunisia and the Southern Region Final Report Part 1 November, 2015 JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc. INGÉROSEC Corporation EI JR 15 - 201 Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in Republic Project Republic of Tunisia Ministry of Development, Investment, and International Cooperation (MDICI), South Development Office (ODS) Project on Regional Development Planning of the Southern Region in the Republic of Tunisia Final Report Part 1 Current Status of Tunisia and the Southern Region Final Report Part 1 November, 2015 JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) Yachiyo Engineering Co., Ltd. Kaihatsu Management Consulting, Inc. INGÉROSEC Corporation Italy Tunisia Location of Tunisia Algeria Libya Tunisia and surrounding countries Legend Gafsa – Ksar International Airport Airport Gabes Djerba–Zarzis Seaport Tozeur–Nefta Seaport International Airport International Airport Railway Highway Zarzis Seaport Target Area (Six Governorates in the Southern -

Information Report on the Municipal Elections in Tunisia (6 May 2018)

35th SESSION Report CG35(2018)10prov 24 September 2018 Information report on the municipal elections in Tunisia (6 May 2018) Rapporteur:1 Xavier CADORET, France (SOC, L) Summary Following the invitation by the Tunisian Government, the Congress deployed an Electoral Assessment Mission of reduced scope to observe the municipal elections in Tunisia on 6 May 2018, which were the first elections held in this country at the local level after the Arab Spring of 2011. The Congress delegation welcomed the fact that, despite difficult structural conditions, both in terms of the political and socio-economic situation of the country, the vote was successfully accomplished and carried out, by and large, in line with international legal standards for elections and good practices. It stressed that the electoral success of truly independent candidates and the number of female, young and disabled candidates who were elected gives rise to hope for further democratic progress at the local level. In view of the low turnout, not least due to the socio-political situation and political disenchantment in the country, particular attention should be paid, according to the Congress, to the situation of the media, especially with regard to the creation of a regulatory framework which allows for a fully-fledged electoral campaign as part of a genuine democratic environment of elections. Simplification also with regard to eligibility requirements and the submission of candidatures could be conducive to the political participation process in general. The Congress concludes that in the medium term, until the next municipal elections, the Tunisian authorities should strive for strengthening of the local level and further decentralisation steps which involve extraordinary opportunities for the country as a whole. -

Unclassified United States International Development

UNCLASSIFIED - - I UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT WASHINGTON, D. C. 20523 PROJECT PAPER . AMENDMENT NO. 1 I TUNISIA : Rural Comuni ty Heal th 664-0296 JUNE 1981 I UNCLASSIFIED AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL OEVSLOPMENT UWtTRD aTATES A. I. 0 MlmmtOM TO TUNlWA FIRST AMENDMEXT PROJECT AUTHORIZATION Name of Country: Re ublic of Name of Project:Rural Community -kizir Health Number of Project: 664-0296 The Rural Community Health Project for the Republic of Tunisia was authorized by the Assistant Administrator for the Near East on September 22, 1977. That authorization. Pursuant to specific redelegation by the Acting Assistant ~dministrator, Bureau for the Near East, is hereby amended as follows: 1. Pursuant to Section 104 of the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, I hereby authorize for the Project additional planned obligations of not to exceed Two Million Three Hundred Ninety Thousand U.S. Dollars ($2,390,000) in loan funds (the "Loan Amendment") and One Nillion Two Hundred Forty Thousand U. S. Dollars ($1,240,000) in grant funds (the "Grant Amendment") during FY 1981 subject to the availability of fmds in accordance with the A.I.D. OYBIallotment process, to help in financing foreign exchange and local crrrrency costs for the Project. 2. The second paragraph of the original project authorization is revised by: (a) deleting the first sentence thereof and substituting the following: "The Project is designed to enhance the quality and coverage of health services in four rural provinces of Tunisia, Gafsa, I<asserine, Siliana and Sidi Bouzid; " and (b) deleting from the third sentence thereof "forty (40)" and substituting therefor "sixty (60)." 3. -

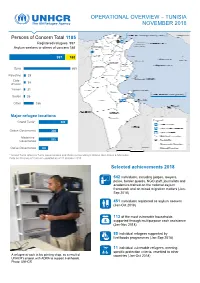

Operational Overview – Tunisia November 2018

OPERATIONAL OVERVIEW – TUNISIA NOVEMBER 2018 Persons of Concern Total 1185 Registered refugees 997 Asylum-seekers or others of concern 188 997 188 Syria 865 Palestine 39 Côte 38 d'Ivoire Yemen 31 Sudan 26 Other 186 Major refugee locations Grand Tunis* 309 Gabes Governorate 208 Medenine 205 Governorate Gafsa Governorate 101 * Grand Tunis refers to Tunis Governorates and those surrounding it: Ariana, Ben Arous & Manouba Data on Persons of Concern updated as of 31 October 2018 Selected achievements 2018 542 individuals, including judges, lawyers, police, border guards, NGO staff, journalists and academics trained on the national asylum framework and on mixed migration matters (Jan- Sep 2018) 451 individuals registered as asylum seekers (Jan-Oct 2018) 113 of the most vulnerable households supported through multipurpose cash assistance (Jan-Nov 2018) 88 individual refugees supported by livelihoods programmes (Jan-Sep 2018) 11 individual vulnerable refugees, meeting specific protection criteria, resettled to other A refugee at work in his printing shop, as a result of countries (Jan-Oct 2018) UNHCR's project with ADRA to support livelihoods. Photo: UNHCR Key priorities for 2019 . Advocating for adoption of the drafted national asylum law and, through continued capacity building, supporting the Tunisian uptake of best practices in the interim. Continuing profiling, registration and refugee status determination in order to identify persons in need of international protection in the context of mixed migration. Promoting refugees’ self-reliance through supporting access to livelihoods and to basic services, as well as prioritizing direct assistance to the most vulnerable. Key challenges for 2019 . Comprehensive domestic legislation to establish a national protection system for refugees and asylum-seekers was drafted in 2016 but has not yet been adopted as law. -

Mediation and Peacebuilding in Tunisia: Actors and Practice

Helpdesk Report Mediation and peacebuilding in Tunisia: actors and practice Alex Walsh1 and Hamza Ben Hassine2 8 April 2021 Questions • Which government and non-government institutions and civil society actors in Tunisia are able to mediate conflict or facilitate peacebuilding at a local and/or national level? • How has their role and capacity changed over time? • How does gender shape roles and capacities? • What does this look like in practice? With regards to: a. Human rights b. Women’s rights c. Economic rights and natural resources Contents 1. Overview 2. Trends in mediation and peacebuilding in Tunisia 3. Mediation and peacebuilding in practice 4. References 5. Annex A. Organisations involved in Peacebuilding and Mediation 1 Coordinator, Algerian Futures Initiative 2 Independent Researcher The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk-based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of FCDO, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Overview This Helpdesk Report is part mapping of the mediation and peacebuilding actors in Tunisia and part review of the available literature. There are a host of governmental and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that are involved in mediation of conflicts and peacebuilding, both in formal and informal ways. -

PROTECTED AREAS & NATURE RESERVES National Park

welcome to… TUNISIA TUNISIA Located in the Maghreb region, on the African continent Official language: Arabic Population: 11.5 million Tourism Contribtuion to GDP: 7-8% TOURISM IN TUNISIA • Gabes: Matmata, Toujene, Villages Berbères • Mednine: Zammour, Beni Khdech • Ben Arous: Jbal Ressass, National park of Boukornine, Sidi Salem Garci DESTINATION TOURISM GOVERNANCE Business Host Community Public Sector Knowledge Sector & Costumers Community Government Tourism offer Local International holders/suppliers Community Organizations Local and Regional Research Intermediaries Tourists Authorities Centers Tourism Transport Business Training Centers Organizations Business Sector (Exluding Tourism Sector) Professional Associations INFRASTRUCTURE & MOBILITY • Accessible through land and air and serviced by a railway • Around 15 special experiences • 130 Hotels • 10 Hostels • 14 Rural houses • 44 Travel agencies PROTECTED AREAS & NATURE RESERVES Tunisia counts 17 National Parks and 27 natural reserves : Tunisian National parks: National Park of Bouhedma, Gafsa and Sidi Bouzid Governorate National Park of Boukornine, Ben Arous Governorate National Park of Chambi, Kasserine Governorate National Park of Dghoumès, Tozeur Governorate National Park of El Feija, Jendouba Governorate National Park of Ichkeul, Bizerte Governorate National Park of Jbil, Kebili Governorate National Park of Djebel Chitana-Cap Negro, Beja and Bizerte Governorate National Park of Djebel Mghilla, Kasserine and Sidi Bouzid Governorate National Park of Djebel Orbata, Gafsa Governorate -

Chemical and Mineralogy Characteristics of Dust Collected

ntal & A me na n ly o t ir ic v a Raja, J Environ Anal Toxicol 2014, 4:6 n l T E o Journal of f x o i l c DOI: 10.4172/2161-0525.1000234 o a n l o r g u y o J Environmental & Analytical Toxicology ISSN: 2161-0525 ResearchResearch Article Article OpenOpen Access Access Chemical and Mineralogy Characteristics of Dust Collected Near the Phosphate Mining Basin of Gafsa (South-Western of Tunisia) Mohamed Raja*, Taieb Dalila and Ben Brahim Ammar Research Unit: Applied Thermodynamics (UR11 ES 80), National Engineering School of Gabes, Gabès University, Tunisia Abstract The study aimed at chemical and mineralogical characterization of whole particulate matter (PM) in the vicinity of a mining phosphate basin at urban area in Gafsa. Heavy metals concentrations in PM samples (Cd, Fe, Cu, Mn, Cr, Zn, Ni, Al, Pb), MgO and SiO2 were determined by atomic absorption spectrometry. Calcium and phosphorus oxides (CaO, P2O5) were analyzed by Technicon Auto-analyzer. Potassium and sodium oxides (K2O, Na2O) were analyzed by flame 2- - - photometer. Ionic species (S04 , Cl , NO3 ) were quantified by ion chromatography while organic carbon (OC) content was determined using carbon sulfur Analyzer. The mineral phase identified by X-Ray powder diffraction technique and SEM-EDX provides information about morphology and chemical composition of PM. As regards the chemical characterization it was found that samples were enriched predominantly in SiO2, CaO and P2O5 which were detected only at mining area (S2 and S3) Weak concentrations of K2O, Na2O and MgO were also found. In addition the minerals phases identified in the samples were carbonate fluorapatite, Calcite, Heulandite, Gypsum and Dolomite. -

Economic Brief

AfDB 2014 www.afdb.org Economic Brief CONTENTS Industrial Policy at the Service of Balanced Territorial Development in Summary p.1 Tunisia 1 – Introduction p.2 2 – Agglomeration, Spatial Disparities and Industrial Policies: Brief Overview of the Theoretical and Summary Empirical Literature p.3 3- Analysis of Industrial he purpose of this study is to analyse the more developed, have relatively diversified Sector Spatial T extent to which new industrial policy industrial activities; and, secondly, the Concentration in components can facilitate the achievement of governorates in the hinterlands and in southern more balanced territorial development in Tunisia, which are less developed, have a less- Tunisia p.5 Tunisia. To that end, we initiated a statistical diversified industrial structure. To guarantee the 4- Agglomeration of analysis of spatial concentration in Tunisia by achievement of more balanced industrial Industrial Activities in calculating the Herfindahl and Ellison & Glaeser development, we propose the adoption of new Tunisia: An Exploratory indices of the various regions and industrial industrial policy components that will generate sectors. We then studied the interactions synergies of proximity between hinterland Analysis of Spatial Data p.12 between neighbouring regions to determine the governorates and their coastal neighbours in 5- Conclusion: Industrial agglomeration of industrial activities using order to trigger a partial migration of labour- spatial data exploratory analysis tools. The intensive activities to disadvantaged regions. Policy Implications p.17 empirical results show that Tunisia’s industrial Such regions will have to start by optimizing Annexes p.21 fabric has two spatial agglomeration patterns: their current specialties before embarking on first of all, the coastal governorates, which are diversification. -

Local Disparity and Perspectives of Territorial Development in Southeastern Tunisia

Local disparity and perspectives of territorial development in southeastern Tunisia ANND 2018 Study Week on Marcoeconomic, Trade and Investment Policies Alumnus RIADH BECHIR- Arid Regions Institute (IRA) Medenine, Tunisia Résumé : En Tunisie, les déséquilibres south-east in 2010. This paper tries to highlight régionaux ont été parmi les grandes révélations the territorial development in the governorates de la Révolution de janvier 2011, cette disparité of South-East Tunisia on the border with est pas seulement entre les gouvernorats, mais Libya. This work proposes to aggregate a set elle s’observe aussi entre les délégations d’un of regional development indicators in order to même gouvernorat. Ce papier tente de mettre draw up a typology of the delegations as well en évidence la disparité territoriale entre les as to calculate a territorial development index délégations des gouvernorats de Sud-Est for each delegation and to discern any failures tunisien en calculant un indice de développement hindering their development. The index of territorial. Ainsi, des recommandations seront territorial development makes it possible to draw proposées afin de réaliser un développement up a typology of the regions according to their équitable. resemblance on the basis of the development Mots clés : disparité territoriale, indice de indicators, which can give us a good illustration développement territorial, Sud-Est tunisien. on the existence or the nonexistence of territorial disparities in the South-East of Tunisia . Abstract: For several decades, Tunisia has been treated as a single entity in national economic REGIONAL DISPARITY IN TUNISIA development. However, the experiences and problems vary conidered by locale within the nation.