12 WP Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![PPA Public Affairs | 7/1/2016 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8998/ppa-public-affairs-7-1-2016-pdf-28998.webp)

PPA Public Affairs | 7/1/2016 [PDF]

Vol. 7, Issue 4 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin May—Jun 2016 E-Bulletin Public Procurement Authority Accounting For Efficiency & Transparency in the Public Procurement System-The Need For Functional Procurement Units Inside this i s s u e : Editorial : Ac- counting For Efficiency &Transparency —Functional Procurement Units Online Activities : Page 2 Challenges With Establishing Functional Pro- curement Units Page 4 & 5 Corruption Along the Public Pro- curement Cycle - Page 6 & 7 (Continued on page 5) Public Procurement (Amendment) Bill, 2015 Passed. More Details Soon ………. Page 1 Public Procurement Authority: Electronic Bulletin July— Aug 2016 Vol. 7, Issue 4 Online Activities List of entities that have submitted their 2016 Procurement Plans Online As At June 30 , 2016 1. Abor Senior High School 58. Fanteakwa District Assembly 2. Accra Polytechnic 59. Fisheries Commission 3. Accra College of Education 60. Foods and Drugs Board 4. Adiembra Senior High School 61. Forestry Commission 5. Adisadel College 62. Ga South Municipal Assembly 6. Aduman Senior High School 63. Ghana Aids Commission 7. Afadzato South District Assembly 64. Ghana Airports Company Limited 8. Agona West Municipal Assembly 65. Ghana Atomic Energy Commission 9. Ahantaman Senior High Schoolool 66. Ghana Audit Service 10. Akatsi South District Assembly 67. Ghana Book Development Council 11. Akatsi College of Education 68. Ghana Broadcasting Corporation 12. Akim Oda Government Hospital 69. Ghana Civil Aviation Authority 13. Akokoaso Day Senior High School 70. Ghana Cocoa Board 14. Akontombra Senior High School 71. Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons 15. Akrokerri College of Education 72. Ghana Cylinder Manufacturing Company Limited 16. Akuse Government Hospital 73. -

Ghana), 1922-1974

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN EWEDOME, BRITISH TRUST TERRITORY OF TOGOLAND (GHANA), 1922-1974 BY WILSON KWAME YAYOH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APRIL 2010 ProQuest Number: 11010523 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010523 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for Students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE S O A S lTb r a r y ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of local government in the Ewedome region of present-day Ghana and explores the transition from the Native Authority system to a ‘modem’ system of local government within the context of colonization and decolonization. -

South Dayi District

SOUTH DAYI DISTRICT i Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the South Dayi District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Ketu North District Assembly

MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2010-2013) 5 MINISTRY OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT KETU NORTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2010- 2013 Under The Ghana shared growth and development agenda (gsgda) 2010- 2013 PREPARED BY: DISTRICT PLANNING CO-ORDINATING UNIT KETU NORTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY DZODZE, V/R MAY, 2010 KETU NORTH DISTRICT MEDIUM TERM DEVELOPMENT PLAN (2010-2013) TABLE OF CONTENT CONTENTS PAGE TABLE OF CONTENT 2 LIST OF TABLES 7 LIST OF FIGURES 9 LISTS OF ACRONYMS 10 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 12 CHAPTER ONE: PERFORMANCE REVIEW AND DISTRICT PROFILE 1.0 PERFORMANCE REVIEW 1.0.1 Introduction 18 1.0.1 Private Sector Competitiveness 18 1 .0.2 Human Resources Development 20 1.0.3 Good Governance and Civic Responsibility 21 1.0.4 Projects Implemented Outside the DMTDP (2006-2009) 22 1.0.5 Problems/Challenges Faced During Implementation 24 1.0.6 Lessons Learnt 24 1.1 PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS 1.1.1 Location and size 26 1.1.2 Geology and Soil 29 1.1.3 Relief and Drainage 29 1.1.4 Climate 29 1.1.5 Vegetation 29 1.1.6 Implications for Development 29 1.2 SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT 1.2.1 Surface Accessibility 30 1.2.2 Settlements Pattern 32 1.2.3 Geographical Distribution of Services 32 1.2.4 Land Use Planning and Development Control 34 1.2.5 Land Administration and the Land Market 35 1.2.6 Housing 35 1.2.7 Industry, Commerce and Service 35 1.2.8 Small Scale Industrial Activities 36 1.2.9 Trade and Commerce 36 1.2.10 Financial Services 37 1.2.11 Telecommunications and Postal Services 37 1.2.12 Filling Stations/Liquefied Petroleum Gas -

MAC ADVICE Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing Activities

MAC ADVICE Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing activities by Ghana’s industrial trawl sector and the European Union seafood market Brussels, 11 January 2021 1. Background The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) has published a report detailing ongoing and systemic illegal practices in Ghana’s bottom trawl industry1. The findings are indicative of a high risk that specific seafood species caught by, or in association with, illegal fishing practices continues to enter the EU market, and that EU consumers are inadvertently supporting illegal practices and severe overfishing in Ghana’s waters. This is having devastating impacts on local fishing communities, and the 2.7 million people in Ghana that rely on marine fisheries for their livelihoods2, as well as a negative impact on the image and reputation of those operators who are deploying good practices. The EU is Ghana’s main market for fisheries exports, accounting for around 85% of the country’s seafood export value in recent years3. In 2018, the EU imported 33,574 tonnes of fisheries products from Ghana, worth €157.3 million4. The vast majority of these imports involved processed and unprocessed tuna products, which are out of the scope of the present advice. 1 EJF (2020). Europe – a market for illegal seafood from West Africa: the case of Ghana’s industrial trawl sector. https://ejfoundation.org/reports/europe-a-market-for-illegal-seafood-from-west-africa-the-case-of-ghanas- industrial-trawl-sector. 2 Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2014) Cited in Fisheries Commission (2018). 2018 Annual Report. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development. Unpublished. 3 Eurostat, reported under chapter 03 and sub-headings 1604 and 1605 of the World Customs Organization Harmonized System. -

Law and Governance Toolkit for Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries BEST REGULATORY PRACTICES Environmental Law Institute

OCEAN PROGRAM DECEMBER 2020 Law and Governance Toolkit for Sustainable Small-Scale Fisheries BEST REGULATORY PRACTICES Environmental Law Institute ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This document was prepared by the Environmental Law Institute (ELI) as part of the Fisheries Law in Action Initiative. The primary drafters were Sofia O´Connor, Stephanie Oehler, Sierra Killian, and Xiao Recio-Blanco, with significant input from Jay Austin, Sandra Thiam, and Jessica Sugarman. For excellent research assistance, the ELI team is thankful to Simonne Valcour, Bridget Eklund, Paige Beyer, Gabriela McMurtry, Ryan Clemens, Jarryd Page, Erin Miller, and Aurore Brunet. The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Oak Foundation, and especially to Imani Fairweather-Morrison and Alexandra Marques. For their time and valuable input, and for their patience answering our many questions, we are thankful to the members of the project Advisory Team: Anastasia Telesetski, Cristina Leria, Francisco Javier Sanz Larruga, German Ponce, Gunilla Greig, Jessica Landman, Kenneth Rosenbaum, Larry Crowder, Miguel Angel Jorge, Robin Kundis Craig, Stephen Roady, and Xavier Vincent. Thank you also to Leyla Nikjou of Parliamentarians for Global Action, Lena Westlund and Ana Suarez-Dussan of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), and to participants in expert workshops in Spain, Mexico, South Africa, and Washington D.C. Funding was generously provided by the Oak Foundation. The contents of this report, including any errors or omissions, are solely the responsibility of ELI. The authors invite corrections and additions. The SSF Law Initiative is the result of a strategic partnership between ELI and Parliamentarians for Global Action (PGA) to support governance reforms for sustainable fisheries management. -

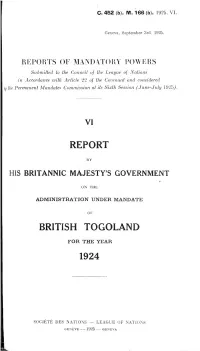

Report British Togoland

c. 452 (b). M. 166 (b). 1925. VI. Geneva, September 3rd, 1925. REPORTS OF MANDATORY POWERS Submitted to the Council of the League of Nations in Accordance with Article 2 2 of the Covenant and considered by the Permanent Mandates Commission at its Sixth Session (June-July 1 9 2 5 J. VI REPORT BY HIS BRITANNIC MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT ON THE ADMINISTRATION UNDER MANDATE OF BRITISH TOGOLAND FOR THE YEAR 1924 SOCIÉTÉ DES NATIONS — LEAGUE OF NATIONS GENÈVE — 1925 ---- GENEVA NOTES BY THE SECRETARIAT OF THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS This edition of the reports submitted to the Council of the League of Nations by the Mandatory Powers under Article 22 of the Covenant is published in exe cution of the following resolution adopted by the Assembly on September 22nd, 1924, at its Fifth Session : “ The Assembly . requests that the reports of the Mandat ory Powders should be distributed to the States Members of the League of Nations and placed at the disposal of the public wrho may desire to purchase them. ” The reports have generally been reproduced as received by the Secretariat. In certain cases, however, it has been decided to omit in this new edition certain legislative and other texts appearing as annexes, and maps and photographs contained in the original edition published by the Mandatory Power. Such omissions are indicated by notes by the Secretariat. The annual report on the administration of Togoland under British mandate for the year 1924 was received by the Secretariat on June 15th, 1925, and examined by the Permanent Mandates Commission on July 6th, 1925, in the presence of the accredited representative of the British Government, Captain E. -

Absences and Epistemologies of Ignorance: a Critical Multi-Sited Study on the Teaching of the Danish Colonial and Slave Trading Past

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 Absences and Epistemologies of Ignorance: A Critical Multi-Sited Study on the Teaching of the Danish Colonial and Slave Trading Past Naja B. Hougaard The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2716 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ABSENCES AND EPISTEMOLOGIES OF IGNORANCE: A CRITICAL MULTI-SITED STUDY ON THE TEACHING OF THE DANISH COLONIAL AND SLAVE TRADING PAST by NAJA BERG HOUGAARD A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 i © 2018 NAJA BERG HOUGAARD All Rights Reserved ii Absences and Epistemologies of Ignorance: A Critical Multi-Sited Study on the Teaching of the Danish Colonial and Slave Trading Past by Naja Berg Hougaard This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Developmental Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________ _______________________________________ Date Anna Stetsenko Chair of Examining Committee _________________ _______________________________________ Date -

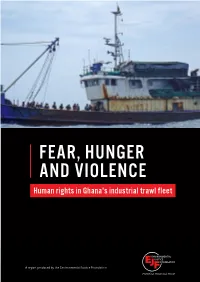

Fear, Hunger and Violence: Human

FEAR, HUNGER AND VIOLENCE Human rights in Ghana's industrial trawl fleet A report produced by the Environmental Justice Foundation 1 OUR MISSION EJF believes environmental security is a human right. EJF strives to: The Environmental Justice Foundation • Protect the natural environment and the people and wildlife (EJF) is a UK-based environmental and human that depend upon it by linking environmental security, human rights charity registered in England and rights and social need Wales (1088128). • Create and implement solutions where they are needed most – 1 Amwell Street training local people and communities who are directly affected London, EC1R 1UL to investigate, expose and combat environmental degradation United Kingdom and associated human rights abuses www.ejfoundation.org • Provide training in the latest video technologies, research and advocacy skills to document both the problems and solutions, This document should be cited as: EJF (2020) working through the media to create public and political Fear, hunger and violence: Human rights in platforms for constructive change Ghana's industrial trawl fleet • Raise international awareness of the issues our partners are working locally to resolve Our Oceans Campaign EJF’s Oceans Campaign aims to protect the marine environment, its biodiversity and the livelihoods dependent upon it. We are working to eradicate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing and to create full transparency and traceability within seafood supply chains and markets. We conduct detailed investigations The material has been financed by the Swedish into illegal, unsustainable and unethical practices and actively International Development Cooperation Agency, promote improvements to policy making, corporate governance Sida. Responsibility for the content rests entirely and management of fisheries along with consumer activism and with the creator. -

A Case Study of Ketu South Municipal Assembly (Ksma)

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh UNIVERSITY OF GHANA THE IMPACT OF FISCAL DECENTRALISATION ON LOCAL ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN GHANA: A CASE STUDY OF KETU SOUTH MUNICIPAL ASSEMBLY (KSMA) BY EMMANUEL JEFFERSON KWADJO ZUMEGAH (10443139) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MPHIL PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION DEGREE JULY, 2015 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DECLARATION I EMMANUEL JEFFERSON KWADJO ZUMEGAH hereby declare that this thesis is my own academic research work towards the award of a master of philosophy degree in Public Administration and that no part of this work has been presented or published. All references used in this work has been fully acknowledged. I therefore take full responsibility for any omissions and commissions herein. ……………………………………….. …………………………….. EMMANUEL JEFFERSON KWADJO ZUMEGAH DATE (10443139) i University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh CERTIFICATION I hereby certify that this thesis was supervised in accordance with procedures laid down by the academic board of the University of Ghana, Legon. …………………………………….. ………………………………… DR. KWAME ASAMOAH DATE (SUPERVISOR) ii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh DEDICATION. To my wife-Mrs. Evelyn Dzifa Melody Zumegah, my kids and to God Almighty iii University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ACKNOWLEDGMENT The highest form of academic dishonesty I could reach is to assume that the entire work of this thesis is as a result of my individual strength. This thesis has been a solid team work between me and my affable supervisor. I express my sincerest gratitude to Dr. -

Heritage at Risk

H @ R 2008 –2010 ICOMOS W ICOMOS HERITAGE O RLD RLD AT RISK R EP O RT 2008RT –2010 –2010 HER ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 I TAGE AT AT TAGE ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER Ris K INTERNATIONAL COUNciL ON MONUMENTS AND SiTES CONSEIL INTERNATIONAL DES MONUMENTS ET DES SiTES CONSEJO INTERNAciONAL DE MONUMENTOS Y SiTIOS мЕждународный совЕт по вопросам памятников и достопримЕчатЕльных мЕст HERITAGE AT RISK Patrimoine en Péril / Patrimonio en Peligro ICOMOS WORLD REPORT 2008–2010 ON MONUMENTS AND SITES IN DANGER ICOMOS rapport mondial 2008–2010 sur des monuments et des sites en péril ICOMOS informe mundial 2008–2010 sobre monumentos y sitios en peligro edited by Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet and John Ziesemer Published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin Heritage at Risk edited by ICOMOS PRESIDENT: Gustavo Araoz SECRETARY GENERAL: Bénédicte Selfslagh TREASURER GENERAL: Philippe La Hausse de Lalouvière VICE PRESIDENTS: Kristal Buckley, Alfredo Conti, Guo Zhan Andrew Hall, Wilfried Lipp OFFICE: International Secretariat of ICOMOS 49 –51 rue de la Fédération, 75015 Paris – France Funded by the Federal Government Commissioner for Cultural Affairs and the Media upon a Decision of the German Bundestag EDITORIAL WORK: Christoph Machat, Michael Petzet, John Ziesemer The texts provided for this publication reflect the independent view of each committee and /or the different authors. Photo credits can be found in the captions, otherwise the pictures were provided by the various committees, authors or individual members of ICOMOS. Front and Back Covers: Cambodia, Temple of Preah Vihear (photo: Michael Petzet) Inside Front Cover: Pakistan, Upper Indus Valley, Buddha under the Tree of Enlightenment, Rock Art at Risk (photo: Harald Hauptmann) Inside Back Cover: Georgia, Tower house in Revaz Khojelani ( photo: Christoph Machat) © 2010 ICOMOS – published by hendrik Bäßler verlag · berlin ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3 CONTENTS Foreword by Francesco Bandarin, Assistant Director-General for Culture, UNESCO, Paris .................................. -

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: the Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6"

"National Integration and the Vicissitudes of State Power in Ghana: The Political Incorporation of Likpe, a Border Community, 1945-19B6", By Paul Christopher Nugent A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.), School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. October 1991 ProQuest Number: 10672604 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672604 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This is a study of the processes through which the former Togoland Trust Territory has come to constitute an integral part of modern Ghana. As the section of the country that was most recently appended, the territory has often seemed the most likely candidate for the eruption of separatist tendencies. The comparative weakness of such tendencies, in spite of economic crisis and governmental failure, deserves closer examination. This study adopts an approach which is local in focus (the area being Likpe), but one which endeavours at every stage to link the analysis to unfolding processes at the Regional and national levels.