PDF File Generated From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (273Kb)

--~-·-----~-.~-.-. ---·--:-~ ---··---:----. -------:------ _________________:~lff1- STATISTISK TELEGRAM STATISTISCHES TELEGRAMM STATISTICAL TELEGRAM ~ TELEGRAMME STATISTIQUE eurostat TELEGRAMMA STATISTICO STATISTISCH TELEGRAM 17.1.1979 :MONTHLY STATISTICS OF REGISTERED UNEMPLOYED IN THE COMMUNITY DECEMBER 197 8 The situation at the end of December 1978 At the end of December 1978 public employment offices in the Community ·registered 6.1 Mio unemployed, that is 5.7% of the civilian working popula tion. Compared to November 1978 the figures show an increase of 1.6%, affecting mainly men and caused by seasonal factors. Seasonally adjusted figures show a slight decrease for the Community as a whole and for those countries which had noticeably hish increases compared with November. The averar{e for the year 1978 The provisional figure for the average number of unemployed in the Community for 1978 is 5 958 000. Compared to 1977- the number of unemployed increased by 3.9%, this increase was however much less important than that from 1976 to 1917 ( + 9.4;~). Some Member-States of the Community sh0\>1 important percentage decreases in the number of their registered unemployed, for instance Ireland (- 7.5%) and the Federal Republic of Germany (- 3.6%). The 1978 figures for the Nether lands and the United Kingdom are sl .ghtly belo\·T those for 1971 (- 0.6/u); on the other hand unemployment has increased during 1978 in Luxembourg, in Den mark(+ 15.5~), in Italy(+ 9.9~), in France(+ 8.9?'~) and in Belgium(+ 8.4/D). In the Community an average of 5.6% of the civilian working population t-:as registered as unemployed in 1978 (5.3% in 1977). -

Johann Streff Book

The Descendents of Johann Streff 1739 - ???? & Barbara Barthel 1734 - ???? Table of Contents Genealogy of Johann Streff ...................................................................................................................................2 Outline Descendant Tree of Johann Streff...........................................................................................................94 Descendant Tree of Johann Streff......................................................................................................................122 Ancestor Tree of Johann Streff..........................................................................................................................233 Index..................................................................................................................................................................234 1 Johann Streff book Descendants of Johann Streff Generation No. 1 1. Johann4 Streff (Petrus3, Arnold2, Johannes1) was born 23 May 1740 in Luxembourg, and died in Luxembourg. He married Barbara Bartel Abt. 1764, daughter of Nicholas Bartel and Barbara Feltes. She was born 3 Nov 1734 in Novis Adibus, Luxembourg, and died in Luxembourg. More About Johann Streff and Barbara Bartel: Marriage: Abt. 1764 Children of Johann Streff and Barbara Bartel are: 2 i. Theodore5 Streff, born 22 Feb 1766 in Gehaunenbusch, Hostert, Luxembourg; died in Luxembourg. + 3 ii. Peter Streff, born 26 Apr 1768 in Gehaunenbusch, Hostert, Luxembourg; died in Luxembourg. + 4 iii. Michel Streff, born -

I Am a Mistake

I am a Mistake A creation by Jan Fabre, Wolfgang Rihm and Chantal Akerman November and December 2007 I. THE PROJECT Jan Fabre has been commissioned by ECHO, the European concert halls organisation, to produce I am a Mistake, a creation in which music, film, dance and theatre are organically fused. A concertante to new music by Wolfgang Rihm for one actor, four dancers of Troubleyn|Jan Fabre, eighteen musicians, with accompaniment from the first note to the last in the form of a film by Chantal Akerman. The Belgian artist Jan Fabre has invited the German composer Wolfgang Rihm to join him for the creation of I am a Mistake. The basis for this creation is an original text by Jan Fabre, entitled I am a Mistake. It is a manifest that amounts almost to a profession of faith by the artist. The blunt confession I am a Mistake is like a mantra that repeats and divides; the voice in this text weaves his web of confessions and meanings, sometimes as a metaphor of an artist sometimes in a protesting tone. Protest against reality and its laws, against matters of fact and their conformism. It comes as no surprise that this piece is dedicated to the subversive film-maker (and amateur entomologist) Luis Buñuel and to Antonin Artaud. I am loyal to the pleasure that is trying to kill me ‘I am a mistake because I shape my life and work organically in accordance with my own judgement with no concern for what one ought to do or say’, this is the artist’s frank summary of his world view. -

Lapland UAS Thesis Template

Islamic finance: current position and its future on the traditional finance market Anna Romozian Thesis Lapland University of Applied Sciences Innovative Business Services 2016 Abstract of Thesis Lapin AMK Innovative Business Services Author Anna Romozian Year 2016 Supervisor Kaisa Lammi Title of Thesis Islamic finance: current position and its future on the traditional finance market No. of pages 30 The objective of this research is to get to know the core principles and concepts of Islamic financial system and to analyze its appearance in non-Muslim coun- tries in order to see the perspectives of Islamic banking on western market. The reason of choosing such topic is explained by rapid growth of Islamic financial institutions in both Muslim and Western countries. This research includes introduction of the main types of contracts of Sharia- based banking, comparison those to ones used in conventional banks; analyz- ing the risks that face Islamic financial institutions in western countries, nuances of the regulation and, in the end, propagation of Islamic banking through the world. The result of the research shows that Islamic financial institutions have the ten- dency to spread further in Europe and in Russia. That means financial authori- ties and traditional banks of those countries have to be prepared to such inno- vation and be ready to face some obstacles. The area of Islamic banking is not explored in depth. That is why the problem of lack of relevant information was faced during that research. the research meth- od used, the research material, results and conclusions. Academic articles, books, web sources and presentations were used as sources. -

21. 5. 79 Official Journal of the European Communities Noc 127/69

21. 5. 79 Official Journal of the European Communities NoC 127/69 MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS OF THE SITTING OF FRIDAY, 27 APRIL 1979 IN THE CHAIR: MR MEINTZ administration of Community tariff quotas for certain wines having a registered designation of Vice-President origin, falling within subheading ex 22.05 C of the Common Customs Tariff and originating in The sitting was opened at 9 a.m. Algeria (1979 to 1980) — (Doc. 41/79); proposal from the Commission of the European Communities to the Council for a Directive Approval of minutes amending for the second time the Annex to Directive 76/769/EEC on the approximation of The minutes of the previous day's sitting were the laws, regulations and administrative provisions approved. of the Member States relating to restrictions on the marketing and use of certain dangerous sub stances and preparations (Doc. 49/79). Procedure without report Since no member had asked leave to speak and no amendments had been tabled to them, the President Accession by the Community to the European declared approved under the procedure without Convention on Human Rights (vote) report laid down in Rule 27A of the Rules of Procedure the following Commission proposals, Parliament then voted on the motion for a resolution which had been announced at the sitting of Monday, contained in the report by Mr Scelba (Doc. 80/79); 23 April 1979: the preamble and paragraph 1 were adopted. — proposal from the Commission of the European On paragraph 2, Mr Scott-Hopkins had tabled Communities to the Council for a Directive amendment No 1 seeking to replace this paragraph by supplementing the Annex to Directive a new text. -

How to Make a Market: Reflections on the European Union's Single

How to Make a Market: Reflections on the Attempt to Create a Single Market in the European Union Author(s): Neil Fligstein and Iona Mara-Drita Source: American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 102, No. 1 (Jul., 1996), pp. 1-33 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2782186 . Accessed: 23/09/2011 12:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Sociology. http://www.jstor.org How to Make a Market: Reflections on the Attempt to Create a Single Market in the European Union1 Neil Fligsteinand Iona Mara-Drita Universityof California,Berkeley Theoriesabout institution-buildingepisodes emphasize either ratio- nal or social and culturalelements. Our researchon the Single Market Program(SMP) of the European Union (EU) shows that both elementsare part of the process. When the EU was caught in a stalemate,the European Commissiondevised the SMP. The commissionworked within the constraintsof existinginstitutional arrangements,provided a "culturalframe," and helped create an elite social movement.This examinationof the SMP legislation, usingan institutionalapproach to the sociologyof markets,shows how the commissionwas able to do thisby tradingoff the interests of importantstate and corporateactors. -

The European Economic Community- a Profile

Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business Volume 3 Issue 2 Fall Fall 1981 The urE opean Economic Community -- A Profile Utz P. Toepke Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njilb Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Utz P. Toepke, The urE opean Economic Community -- A Profile, 3 Nw. J. Int'l L. & Bus. 640 (1981) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of International Law & Business by an authorized administrator of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. The European Economic Community- A Profile Utz P. Toepke* To enable those readers who may be unfamiliar with the history and structure of the European Economic Community to better understandthe articles in this symposium, Dr. Toepke reviews the background,the institu- tions and the underlying theory of this unique legalphenomenon. INTRODUCTION Two main objectives underlie this article. Initially, the readers of this symposium on the European Economic Community (EEC) need a descriptive overview in order to understand and appreciate the phe- nomenon called the Common Market which has now existed in West- ern Europe for a quarter century. Thus, a point of reference will be provided for the detailed discussion of a variety of legal and social is- sues in the EEC by the distinguished writers in this symposium. Sec- ondly, these issues will .be put in perspective by showing that everything relating to the EEC is subject to the overriding objective mandated by its constitutive charter, the Treaty of Rome-namely the objective of integrating ten separate economies and distinctly different societies. -

Oincial Journal C 127 C U "C R^ ' ' Volume 22

j*-*^ /"/"••'IT *f ISSN 0371-6986 Oincial Journal c 127 C U "C r^ ' ' Volume 22 Oi trie -cAiropeaxi v^ornniiinitics 21 May 1979 ContentEnglishs edition I InformatioInformation n and Notices European Parliament 1979/80 session Minutes of the sitting of Monday, 23 April 1979 1 Order of business 12 Youth policy in the Community (debate including the oral question with debate by Mr Schreiber, Mr Kavanagh, Mr Albers, Mr Hoffmann, Mr Hoist and Mr Seefeld to the Commission: Youth policy in the Community) 16 Second European Social Budget (1976 to 1980) (debate) 16 Minutes of the sitting of Tuesday, 24 April 1979 17 Draft amending and supplementary budget No 1 for 1979 (debate) 18 Regulation on interest rebates for loans with a structural objective (debate) 18 Opinion on the proposal for a Decision on setting up a second joint programme of exchanges of young workers within the Community 19 Resolution on the Second European Social Budget (1976 to 1980) 20 Regulation on interest rebates for loans with a structural objective (continuation of debate) 21 Decision empowering the Commission to contract loans for promoting investment (debate) 21 Regulation amending the Staff Regulations of officials of the Communities (debate) 22 Administrative expenditure of the European Parliament during the 1978 financial year (debate) 22 Oral question with debate by Mr Bangemann, Mr Cifarelli, Mr Damseaux, Mr Johnston and Mr Jung to the Commission; Reserve for the non-quota section of the Regional Fund 22 Decision on coal and coke for the iron and steel industry (debate) -

Press Kit Never for MONEY, ALWAYS for LOVE DESIGN CITY 2014 – LXBG BIENNALE

press kit neVer FOr MOneY, ALWAYs FOr LOVe DesiGn CitY 2014 – LXBG BiennALe 03/04/2014 – 15/06/2014 MUDAM LUXeMBOUrG Anne Genvo & David Richiuso, Copier/Couler, 2013, © photo: Anne Genvo mudaM Mudam Luxembourg never for Money, page Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean Always for Love 2 neVer FOr MOneY, ALWAYs FOr LOVe DesiGn CitY 2014 – LXBG BiennALe press kit sUMMArY press reLeAse 03 ADDress AnD inFOrMAtiOn 04 AnA ritA AntÓniO 06 BrUnO CArVALHO 07 BernArDO GAeirAs 08 GiLLes GArDULA 09 Anne GenVO & DAViD riCHiUsO 10 Anne-MArie HerCkes 11 Les M stUDiO 12 MAUriCe + pAULA 13 rUi pereirA 14 LYnn sCHAMMeL (sOCiALMAtter) 15 DAnieLA pAis 15 sUsAnA sOAres 16 JOÃO VALente 17 AnseLM JAppe: DesiGn, tHe ULtiMAte stAGe OF CApitALisM? 18 Mudam Luxembourg never for Money, page Musée d’Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean Always for Love 3 Press release neVer FOr MOneY, ALWAYs FOr LOVe DesiGn CitY 2014 – LXBG BiennALe Thirteen designers from Portugal and Luxembourg present original projects that are all possible responses to issues concerning the manufacturing process, sustainability and the preservation of environmental and human resources. An exhibition on the social role of design that gives new meaning to the discipline. Mudam is presenting the exhibition Never for Money, Always for Love as part of Design City 2014. Conceived as a platform for exchange between Luxembourg and Portugal, it brings together thirteen designers who incorporate a critical and responsible approach in their design practice. The exhibition is the exact opposite of consumerism and examines traditional design production methods in order to meet the challenges of the contemporary political and social context. -

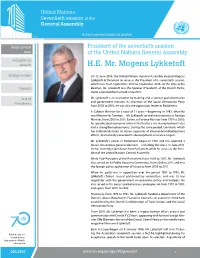

H.E. Mr. Mogens Lykketoft

United Nations Seventieth session of the General Assembly A new commitment to action President of the seventieth session of the United Nations General Assembly H.E. Mr. Mogens Lykketoft On 15 June 2015, the United Nations General Assembly elected Mogens Lykketoft of Denmark to serve as the President of its seventieth session, which runs from September 2015 to September 2016. At the time of his election, Mr. Lykketoft was the Speaker (President) of the Danish Parlia- ment, a position he has held since 2011. Mr. Lykketoft is an economist by training and a veteran parliamentarian and government minister. As chairman of the Social Democratic Party from 2002 to 2005, he was also the opposition leader in Parliament. A Cabinet Minister for a total of 11 years — beginning in 1981, when he was Minister for Taxation — Mr. Lykketoft served most recently as Foreign Minister, from 2000 to 2001. Earlier, as Finance Minister from 1993 to 2000, he spearheaded economic reforms that led to a rise in employment rates and a strengthened economy. During the same period, Denmark, which has traditionally been an active supporter of international development efforts, dramatically exceeded its development assistance targets. Mr. Lykketoft’s career in Parliament began in 1981 and has spanned a dozen consecutive general elections — including the latest, in June 2015. He has currently taken leave from Parliament while he serves as the Presi- dent of the United Nations General Assembly. While Vice-President of the Parliament from 2009 to 2011, Mr. Lykketoft also served on its Public Accounts Committee, from 2006 to 2011, and was the foreign policy spokesman of his party from 2005 to 2011. -

Science for the People Magazine Vol. 12, No. 5

BIODCHNOLOGY BECOMES BIG BUSINESS 1\UfA'-.., lJHlr ('C) .$ r~ r.t:i df ~MW.: h.\ ~ 11l\M~ to bring to your attention another group of pesticides whose danger is just letters beginning to be recognized. The studies which I summarize further emphasize and support a number of important points about the danger of these com pounds brought out in your article. Dear SftP: reality in separating civil disobedience It is well known that the effect pro I found much to agree with in your and elections. If by "lack of reality" he duced by a toxic chemical depends upon "Prospects and Problems" (July/ Aug.; means that this separation is strate a) the dose, b) the length of exposure, 1980) article on the antinuclear move gically and tactically incorrect, then I and c) the route of administration of the ment. I share a real concern that the certain!}' agree. If, however. he means toxic substance. This i~ important in movement I belong to - the pacifist that a split does not exist in the move view of the fact that the petrochemical movement - often uses civil disobed ment her ween tho.5e participating in di industry is getting increasingly involved ience and direct action in a "reflexive" rect action and those emphasizing in studying toxicology. However, their way, that consensus can become anti "legalistic" activities. then /think he is focus is on acute and subacute toxicol democratic, anarchism is often an irres engaging in jamasy. Certainly there are ogy. The chronic effects due to long term ponsible evasion of problems of power, many groups and individuals. -

Family Tree Maker 2005

The Descendents of Johann Streff 1739 - ???? & Barbara Barthel 1734 - ???? Table of Contents NGS Quarterly Report of Johann Streff.................................................................................................................2 Outline Descendant Tree of Johann Streff...........................................................................................................79 Descendant Tree of Johann Streff......................................................................................................................103 Index..................................................................................................................................................................196 1 Johann Streff book Descendants of Johann Streff Generation No. 1 1. Johann2 Streff (Johanne1) was born 23 May 1740 in Luxembourg, and died in Luxembourg. He married Barbara Bartel Abt. 1764, daughter of Nicholas Bartel and Barbara Feltes. She was born 3 Nov 1734 in Novis Adibus, Luxembourg, and died in Luxembourg. More About Johann Streff and Barbara Bartel: Marriage: Abt. 1764 Children of Johann Streff and Barbara Bartel are: 2 i. Theodore3 Streff, born 22 Feb 1766 in Gehaunenbusch, Hostert, Luxembourg; died in Luxembourg. + 3 ii. Peter Streff, born 26 Apr 1768 in Gehaunenbusch, Hostert, Luxembourg; died in Luxembourg. + 4 iii. Michel Streff, born 24 Sep 1773 in Neunhaüsen, Luxembourg; died Unknown in Luxembourg. Generation No. 2 3. Peter3 Streff (Johann2, Johanne1) was born 26 Apr 1768 in Gehaunenbusch, Hostert, Luxembourg,