Copyright by Christopher John Mayer 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSA/CHICAGO at the University of Chicago

A publication by students of the School of Social Service Administration SSA/CHICAGO at the University of Chicago Advocates’ FORUM 2006 Advocates’ FORUM 2006 COEDITORS IN CHIEF Charlotte Hamilton Amy Proger EDITORIAL BOARD Vanessa Askot Stephen Brehm Marianne Cook Jessica Falk Charlotte Hamilton Christina James Amy Proger Liz Schnitz Marion Scotchmer Aaron Willis ADVISOR Virginia Parks, Ph.D. MISSION STATEMENT Advocates’ Forum is an academic journal that explores clinical implications, social issues, admin- istration, and public policies linked to the social work profession. The journal is written, edited, and ESSAYS AND ARTICLES created by students of the School of Social Service Administration, Mapping the American Political Stream: and its readership includes current The Stuart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act students, alumni, faculty, fieldwork by Betsy Carlson . 6 supervisors, and other professionals in the field. The editors of Advocates’ The Stink beneath the Ink: How Cartoons Are Forum seek to provide a medium through which SSA students Animating the Gay and Lesbian Culture Wars can contribute to the continuing by Frank Baiocchi . 16 discourse on social welfare and policy. Those of a Queer Age: Insights into Aging in the Gay and Lesbian Community EDITORIAL POLICY by Stephanie Schmitz-Bechteler . 26 Advocates’ Forum is published by the students of the School of Transgender Inclusion and Feminism: Social Service Administration Organizations and Innovation (SSA) at the University of Chicago. by Katherine S. Stepleton . 37 Submissions to the journal are selected by the editorial board from An Introduction to the Client-Oriented, Practical, works submitted by SSA students and edited in an extensive revision Evidence Search (COPES) process with the authors’ permis- by Aaron Willis and Andrew Gill . -

Yearbook 2008 African

AFRI Yearbook 2008 CAN M E DI A AFRIcan , AFRI , CAN MEDIA, C H ILDR AFRIcan The International Clearinghouse EN on Children, Youth and Media Norma Pecora, Enyonam Osei-Hwere & Ulla Carlsson CHILDRen NORDICOM Nordic Information Centre for Media and Communication Research University of Gothenburg Editors: Box 713, SE 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Norma Pecora, Enyonam Osei-Hwere & Ulla Carlsson Telephone: +46 31 786 00 00 Fax: +46 31 786 46 55 E-mail: nordicom @nordicom.gu.se www.nordicom.gu.se WITH AN INTRODUCTIon BY FIRDOZE BULBULIA ISBN 978-91-89471-68-9 The International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media NORDICOM University of Gothenburg Yearbook 2008 The International The International Clearinghouse Clearinghouse on Children, Youth and Media, at on Children, Youth and Media A UNESCO INITIATIVE 1997 Nordicom University of Gothenburg Box 713 SE 405 30 GÖTEBORG, Sweden In 1997, the Nordic Information Centre for Media Web site: and Communication Research (Nordicom), Göteborg www.nordicom.gu.se/clearinghouse University Sweden, began establishment of the International Clearinghouse on Children, Youth DIRECTOR: Ulla Carlsson and Media. The overall point of departure for the SCIENTIFIC CO-ORDINATOR: Clearinghouse’s efforts with respect to children, youth Cecilia von Feilitzen Tel:+46 8 608 48 58 and media is the UN Convention on the Rights of the Fax:+46 8 608 46 40 Child. [email protected] The aim of the Clearinghouse is to increase INFORMATION CO-ORDINATOR: awareness and knowledge about children, youth and Catharina Bucht media, thereby providing a basis for relevant policy- Tel: +46 31 786 49 53 making, contributing to a constructive public debate, Fax: +46 31 786 46 55 [email protected] and enhancing children’s and young people’s media literacy and media competence. -

NHPTV Ready to Learn Enhance Learning with the Learning Triangle

Enhance Learning with the Learning Triangle We all have different learning styles: Visual (what we see) Auditory (what we hear) Tactile/kinesthetic (what we feel or do) The VIEW-READ-DO Learning Triangle combines all three by using related video, books, and activities about any theme or subject. The first step is to videotape children’s programs so that you can: preview; show at your convenience; watch over and over; and use as an effective teaching and learning tool by being able to cue, pause or stop, fast forward and rewind the tape. You can show specific short segments, discuss with children what they see, have them predict what might come next, explain new vocabulary words, and relate to a child’s own experiences. Visit www.nhptv.org/programs.schedule.asp for program schedule and a brief description of episode content and focus. Then, find age-appropriate books to read aloud and plan activites for children to do--draw pictures, act out or retell the story, projects, field trips. Add the Learning Triangle to your teaching toolbox. NHPTV Ready To Learn Pat VanWagoner, RTL Coordinator, (603) 868-4352, [email protected] Nancy Pearson, Education Assistant, (603) 868-4353, [email protected] FAX: (603) 868-7552 Web Site: www.nhptv.org/rtl Ready To Learn Education Partners: Norwin S. & Elizabeth Bean Foundation, The Byrne Foundation, Benjamin Couch Trust, Jefferson Pilot Financial, The Linden Foundation, Samuel P. Pardoe Foundation, and Verizon. “The contents of this newsletter are supported under the Ready-To-Learn Television Program, P/R Award Number R295A00002, as administered by the Office of Educational Research and Improvement, U.S. -

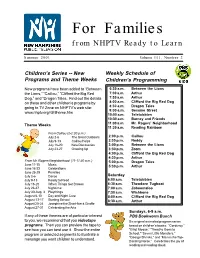

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn

For Families from NHPTV Ready to Learn Summer 2001 Volume III, Number 2 Children’s Series -- New Weekly Schedule of Programs and Theme Weeks Children’s Programming New programs have been added to “Between 6:30 a.m. Between the Lions the Lions,” “Caillou,” “Clifford the Big Red 7:00 a.m. Arthur Dog,” and “Dragon Tales. Find out the details 7:30 a.m. Arthur on these and other children’s programs by 8:00 a.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog going to TV Zone on NHPTV’s web site: 8:30 a.m. Dragon Tales 9:00 a.m. Sesame Street www.nhptv.org/rtl/rtlhome.htm 10:00 a.m. Teletubbies 10:30 a.m. Barney and Friends Theme Weeks 11:00 a.m. Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood 11:30 a.m. Reading Rainbow From Caillou (2-2:30 p.m.) July 2-6 The Great Outdoors 2:00 p.m. Caillou July 9-13 Caillou Helps 2:30 p.m. Noddy July 16-20 New Discoveries 3:00 p.m. Between the Lions July 23-27 Growing Up 3:30 p.m. Zoom 4:00 p.m. Clifford the Big Red Dog 4:30 p.m. Arthur From Mr. Rogers Neighborhood (11-11:30 a.m.) 5:00 p.m. Dragon Tales June 11-15 Music 5:30 p.m. Arthur June 18-22 Celebrations June 25-29 Families July 2-6 Dance Saturday July 9-13 Ready to Read 6:00 a.m. Teletubbies July 16-20 When Things Get Broken 6:30 a.m. -

Banning Gay Books: Protecting Kids Or Censorship? Are Some Voters

A PUBLICATION OF THE NEW JERSEY STATE BAR FOUNDATION WINTER 2006 • VOL.5, NO. 2 A NEWSLETTER ABOUT LAW AND DIVERSITY Banning Gay Books: Protecting Kids or Censorship? by Phyllis Raybin Emert Recently, a number of states, including “This is an embarrassment even by Alabama Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana and Oklahoma standards,” Mark Potok, director of the Southern Poverty have attempted to ban or limit the distribution Law Center’s Intelligence Project, which is based in of books with homosexual themes or homosexual Montgomery, told the School Library Journal. “This authors.The most sweeping legislation of all was could even get the Bible banned.” introduced in Alabama in December 2004.That Allen told Guardian newspaper, “traditional family bill called for all books, plays and writings by gay values are under attack,” and he wants to protect the authors or with gay characters to be banned from people of Alabama from what >continued on page 2 public school libraries. Such a ban would include, just to name a few, the poems of Walt Are Some Voters Being Kept From the Polls? Whitman; The Color Purple, a novel by Barbara Sheehan by Alice Walker; Thornton Wilder’s In America, voting is the cornerstone of our democratic play, Our Town; the works of James society, but what happens when the right to vote is compromised? Baldwin, Edward Albee, Noel Coward, Does discrimination still exist at the polls? Are minorities in Oscar Wilde and Tennessee Williams; particular being discouraged from casting their ballots? Some as well as biographies of any notable voters claim yes. gay personality. -

October 2016 Program Listings Subject to Change

October 2016 Program Listings Subject to Change Be Inspired! Be Informed! Friday, October 21st Tune in Monday-Friday 8pm Hamilton’s America 5:00pm Nightly Business Report Great Performances 5:30 BBC World News America follows the creation of 6:00 PBS NewsHour Lin-Manuel Miranda’s 1:00am Tavis Smiley pop culture Broadway 1:30 NHK Newline phenomenon Hamilton *Subject to change without notice. and the history behind it. Tune in Saturday & Sunday Interviews with Presidents 6:00pm PBS NewsHour Weekend Barack Obama and George Except 10/15 -10/23 W. Bush, Nas, Questlove, Stephen Sondheim and Be Enriched! more. Saturdays 11:00am America’s Test Kitchen 11:30 Cook’s Country Be Entertained! 12:00pm Ellie’s Real Good Food Wednesday, October 12 12:30 Mexico-One Plate at a Time 8pm Nature: Super 1:00 Antiques Roadshow Hummingbirds Enter 2:00 Rick Steves’ Europe the fast-paced world of 3:00 Martha’s Cooking School hummingbirds through 3:30 Martha Bakes high-speed cameras and 4:00 Steven Raichlen’s Project breakthrough science. Smoke ends 10/8 For the first time, see 4:30 New Orleans Cooking W/ Kevin them mate, fight and Belton ends 10/8 raise families. They are 4:00 The Great British Baking Show super hummingbirds— starting 10/29 great athletes, yet tender 5:00 This Old House moms who are up for any For more lifestyle programming challenge! everyday, watch Valley Create on Channel 18.2, Comcast 395 and Brighthouse 242. Saturday, October 1 Sunday, October 2 6:30pm Valley’s Gold Asparagus Ryan Jacobsen 10:30am Market to Market Solid reporting about travels to California’s Delta region to find out about the issues that challenge agriculture. -

A Hidden Culture Anne Wood on How Art Helps Young Children Develop

Perspectives on the value of art and culture Children and the Arts: A Hidden Culture Anne Wood on how art helps young children develop READ ON Anne Wood Back Next 02 Anne Wood is one of the most influential figures in children’s television. Born in Spennymoor, County Durham, she grew up in the mining community of Tudhoe Colliery then began a career as a secondary school teacher. She was a leading voice for children’s literature before launching a career in broadcasting. In 1984, she formed Ragdoll Productions, known for such television series as Rosie & Jim, Tots TV, Brum, In the Night Garden, Twirlywoos – and Teletubbies. She is the founder of The Ragdoll Foundation (www.ragdollfoundation.org.uk), which aims to provide a space for alternative thinking, voices and practices, to seek new creative solutions and partners, and to collaborate and share knowledge. It is currently leading the Save Kids’ Content UK campaign (www.savekidscontent.org.uk), which has the particular objective of safeguarding the production of UK- originated television for children. As a cultural notion, childhood emerged in western society somewhere around the 1850s and lasted until somewhere around the 1950s when the cult of the teenager first made itself felt in the USA, and spread around the world. Now, in the 21st century, we hear children are ‘growing up too fast’ or that ‘childhood is lost’. It is not that children are biologically changing. Although many may be taller, more robust and have greater life expectancy than previous generations, essentially children are no different. They have the same need to explore life and navigate it successfully, which has always been central to humanity. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Using Interactive Reading Techniques with <I>Word World</I> To

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations in Early Childhood Communication Disorders & Special Education Education Winter 2014 Using Interactive Reading Techniques with Word World to Enhance Emergent Literacy James B. Godfrey Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/earlychildhood_etds Part of the Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Language and Literacy Education Commons Recommended Citation Godfrey, James B.. "Using Interactive Reading Techniques with Word World to Enhance Emergent Literacy" (2014). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, Comm Disorders & Special Educ, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/n024-z588 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/earlychildhood_etds/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Disorders & Special Education at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations in Early Childhood Education by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING INTERACTIVE READING TECHNIQUES WITH WORD WORLD TO ENHANCE EMERGENT LITERACY by James B. Godfrey B. A. May 1988, Duke University M. S. August 1997, Old Dominion University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY December 13, 2014 ihen tonelson (Director) ,inaa Bol (Member) igela#ftoff(Mentf>^/) Peter Baker (Member) ABSTRACT USING INTERACTIVE READING TECHNIQUES WITH WORD WORLD TO ENHANCE EMERGENT LITERACY James B. Godfrey Old Dominion University, 2014 Director: Dr. Stephen Tonelson Facets of emergent literacy such as phonological awareness (PA) and alphabet knowledge (AK) are precursors to later conventional literacy (Dockrell, Stuart & King, 2010; Neuman & Dwyer, 2009; NELP, 2008). -

Children's Catalog

PBS KIDS Delivers! Emotions & Social Skills Character Self-Awareness Literacy Math Science Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR,) January 2019 2 Seven in ten children Research shows ages 2-8 watch PBS that PBS KIDS makes an in the U.S. – that’s impact on early † childhood 19 million children learning** * Source: Nielsen NPower, 1/1/2018--12/30/2018, L+7 M-Su 6A-6A TP reach, 50% unif., 1-min, LOH18-49w/c<6, LOH18-49w/C<6 Hispanic Origin. All PBS Stations, children’s cable TV networks ** Source: Hurwitz, L. B. (2018). Getting a Read on Ready to Learn Media: A Meta-Analytic Review of Effects on Literacy. Child Development. Dol:10.1111/cdev/f3043 † Source: Marketing & Research Resources, Inc. (M&RR), January 2019 3 Animated Adventure Comedy! Dive into the great outdoors with Molly of Denali! Molly, a feisty and resourceful 10-year-old Alaskan Native, her dog Suki, and her Facts: friends Tooey and Trini take • Contemporary rural life advantage of their awe-inspiring • Intergenerational surroundings with daily relationships adventures. They also use • Respect for elders resources like books, maps, field • Set against a backdrop of guides, and local experts to Native America culture and encourage curiosity and help in traditions • Producers: Atomic Cartoons and their community. WGBH KIDS • Broadcaster: PBS KIDS Target Demo: 4 to 8 76 x 11’ (Delivered as 38 x 25') + 1 x 60’ special Watch Trailer Watch Full Episode 4 Exploring Nature’s Ingenious Inventions This funny and engaging show follows a curious bunny named Facts: Elinor as she asks the questions in • COMING FALL 2020 every child’s mind and discovers • Co-created by Jorge Cham and the wonders of the world around Daniel Whiteson, authors of We her. -

Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children's Educational Television

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU Honors Projects Honors College Fall 12-11-2017 Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children’s Educational Television Rebecca Wettstein [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Other Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Repository Citation Wettstein, Rebecca, "Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children’s Educational Television" (2017). Honors Projects. 383. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/honorsprojects/383 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Running head: VOCABULARY IN EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION 1 Exploring the Vocabulary Teaching Strategies Used in Children’s Educational Television Rebecca C. Wettstein Bowling Green State University Submitted to the Honors College at Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with University Honors December 11, 2017 Dr. Virginia Dubasik, Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders, Advisor Jeffrey Burkett, College of Education, Advisor VOCABULARY IN EDUCATIONAL TELEVISION 2 Abstract The present study explored the extent to which vocabulary instructional strategies are used in the children’s educational television show Word Girl, and whether or not the occurrences of vocabulary instructional strategies changed over the time the show was aired. Instructional strategies included repetition of target words, labeling, defining/mislabeling, and onscreen print. A total of eighteen episodes between 2007 and 2015 were analyzed. The early time period included episodes aired from 2007-2009, the middle time period included episodes aired from 2010-2012, and the late time period included episodes aired from 2013-2015. -

Arthur WN Guide Pdfs.8/25

Building Global and Cultural Awareness Keep checking the ARTHUR Web site for new games with the Dear Educator: World Neighborhood ® ® has been a proud sponsor of the Libby’s Juicy Juice ® theme. RTHUR since its debut in award-winning PBS series A ium 100% 1996. Like Arthur, Libby’s Juicy Juice, prem juice, is wholesome and loved by kids. itment to a RTHUR’s comm Libby’s Juicy Juice shares A world in which all children and cultures are appreciated. We applaud the efforts of PBS in producingArthur’s quality W orld educational television and hope that Neighborhood will be a valuable resource for teaching children to understand and reach out to one another. Enjoy! Libby’s Juicy Juice Contents About This Guide. 1 Around the Block . 2 Examine diversity within your community Around the World. 6 Everyday Life in Many Cultures: An overview of world diversity Delve Deeper: Explore a specific culture Dear Pen Pal . 10 Build personal connections through a pen pal exchange More Curriculum Connections . 14 Infuse your curriculum with global and cultural awareness Reflections . 15 Reflect on and share what you have learned Resources . 16 All characters and underlying materials (including artwork) copyright by Marc Brown.Arthur, D.W., and the other Marc Brown characters are trademarks of Marc Brown. About This Guide As children reach the early elementary years, their “neighborhood” expands beyond family and friends, and they become aware of a larger, more diverse “We live in a world in world. How are they similar and different from others? What do those which we need to share differences mean? Developmentally, this is an ideal time for teachers and providers to join children in exploring these questions.