Partners in Struggle the Legacy of John Brown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shootouts, Showdowns, & Barroom Brawls

he year is 1870, the place is Kansas, and the hero is Bat Masterson. As Liberal’s new sheriff, he must bring the rowdy cowtown under control. But an evil cattle baron plots T the lawman’s demise even as he vows to tame its mean streets. Is Bat doomed? Can he make the town safe? In the end, will good triumph over evil? You don’t have to see the movie Trail Street to know the guy in the white hat wins. In fact, if you’ve seen one Shootouts, Showdowns, & Barroom Brawls 1940s Western, you’ve pretty much seen them all. The “REAL” TO “REEL” HISTORY — THATWAS genre’s strength is in fast-paced action rather than creative plots. And if gunfights, chases, and a little romance are THE FORMULA DURING THE HEYDAY OF your idea of a good time, then these movies are bound to THE HOLLYWOOD WESTERN.AND IN THE please. FANTASTICAL MIX OF GUNFIGHTS AND Kansas was the subject of many films during the FISTFIGHTS, GOOD GUYS AND BAD,KANSAS Western’s heyday (1930s–1950s), when Hollywood writ- ers and directors had just enough knowledge of the state’s OFTEN PLAYED A STARRING ROLE. history to be dangerous. They inserted famous people and by Rebecca Martin place-names into a formulaic outline, blurring the line be- tween “reel” and “real” history. Thus, generations of youth who spent Saturday afternoons at the local theater came to believe that Bleeding Kansas and the Civil War were (TOP) DRAMATIC SCENE FROM A REB RUSSELL WESTERN.(LEFT) IN THE 1950 FILM GUNMEN OF one and the same, Jesse James was just an unfortunate vic- ABILENE, POPULAR “B” WESTERN STAR ROCKY LANE (AS A U.S. -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room. -

Slavery and the Santa Te Trail 87

slavery and the santa te trail or, John brown on hollywood's sour apple tree robert e. morsberger Robert Morsberger's essay was intended for the special festschrift num ber (xvi, 2) marking Alexander Kern's retirement. We publish it here with this headnote because, though it became ready for publication too late to make that issue, we're happy to go on honoring Alex. The furor after the publication of William Styron's The Confessions of Nat Turner in 1967 demonstrates the intensity of our reactions to Afro-American history in general and to slave insurrections in particular. Americans are being made aware of the insurrections of Cato, Gabriel Prosser, Denmark Vesey and the revolt aboard the Amistad; and Stanley Elkins's theory that slavery reduced blacks in America to passive "sambos" is being challenged. For the most part the insurrectionists are now hailed as heroic freedom fighters whose violence was justified as prisoners of war trying to escape from or overthrow their captors. The complex ambiguity of Styron's treatment of Nat Turner, even though the novel is an ironic indictment of slavery, so angered black militants that they stopped the production of a movie version of the book. From this perspective, it may be profitable to look back and examine the one major Hollywood film that did deal at length with the issue of American slave insurrection. This is Warner Brothers', The Santa Fe Trail, a popular hit of 1940. The film is of considerable interest as a vehicle of popular culture, embodying some of the confusions and prejudices of the pre-civil rights era; and as it is still shown frequently on television, its propaganda, dated though it is, may continue to influence audiences. -

The Bearing in Tbe Above-Entitled Matter Was Reconvened Pursuant

I COPYRIGHT ROYALTY TRIBUNAL lXL UI I 1 I I In the Matter og ~ CABLE COPYRIGHT ROYALTY CRT 85-4-84CD DISTRIBUTION PHASE II (This volume contains page 646 through 733) 10 llll 20th Street, Northwest Room 458 Washington, D. C. 12 Friday, October 31, 1986 13 The bearing in tbe above-entitled matter was reconvened pursuant. to adjournment, at 9:30 a.m. BEFORE EDWARD.W. RAY Chairman 20 MARI 0 F . AGUERO Commissioner 21 J. C. ARGETSINGER Commissioner 23 ROBERT CASSLER General Counsel 24 HEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRIBERS 1323 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, IW.W. {202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 {202) 232-6600 647 APPEARANCES: 2 On beha'lf of MPAA: DENNIS LANE, ESQ. Wilner R Scheiner Suite 300 1200 New Hampshire Avenue, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20036 6 On behalf of NAB: JOHN STEWART, ESQ. ALEXANDRA WILSON, ESQ. Crowell S Moring 1100 Connecticut Avenue, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20036 On behalf of Warner Communicate.ons: ROBERT GARRETT, ESQ. Arnold a Porter 1200 New Hampshire Avenue, Northwest Washington, D. C. 20036 13 On behalf of Multimedia Entertainment: ARNOLD P. LUTZKER, ESQ. 15 Dow, Lohnes a Albertson. 1255 23rd Street, Northwest. Washington, D. C. 20037 On bahalf of ASCAP: I, FRED KOENIGSBERG, ESQ. Senior Attorney, OGC One Lincoln Plaza New York, New York 10023 20 22 23 24 HEAL R. GROSS COURT REPORTERS AND TRANSCRI8ERS I323 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, N.W. (202) 234-4433 WASHINGTON, D.C. 20005 (202) 232-6600 648 CONTENTS WITNESS DIRECT 'CROSS VOIR 'DI'RE TR'QBUNAL 3 , ALLEN R. COOPER 649,664 By Ms. -

Reel Wars: Cold War, Civil Rights and Hollywood's

REEL WARS: COLD WAR, CIVIL RIGHTS AND HOLLYWOOD'S CHANGING INTERPRETATION OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1945-75 J. Roy Collins M. Phil. 2006 . HESISfc tc o:> COL g REEL WARS: COLD WAR, CIVIL RIGHTS AND HOLLYWOOD'S CHANGING INTERPRETATION OF THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1945-75 J. Roy Collins A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the degree of Master of Philosophy March 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Andrew Dawson, for his patient encouragement and for gently keeping me focused, and Michael Zell, for his very pertinent comments, also the library staff at Greenwich who have always been most helpful. My thanks, too, to my son Dan and my friends May Clarke and Jim Murray for struggling through a rather large first draft and Alan Rose for his help in obtaining many of the films on video. Also, my sister Tessa, for her proof reading, and Jacob Veale for his computer expertise. Finally, my partner Sarah for her continual encouragement and support and my daughters Hannah and Esther, who accepted that 'Dad was doing his thing.' in ABSTRACT This study is an examination of America's evolving sense of racial and national identity in the period from 1945 to the mid 1970s as refracted through Hollywood's representation of the American Civil War - a powerful event in American memory which still resonates today. Civil War films have been the subject of study by film studies specialists and historians but they have concentrated on the early years highlighting the iconic films The Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939). -

A Study of the Conspiracy Behind John Brown's Raid. Jeffery S

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1974 The secret six : a study of the conspiracy behind John Brown's raid. Jeffery S. Rossbach University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Rossbach, Jeffery S., "The es cret six : a study of the conspiracy behind John Brown's raid." (1974). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1333. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1333 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SECRET SIX: A STUDY OF THE CONSPIRACY BEHIND JOHN BROWN'S PAID A Dissertation Presented By JEFFERY STUART ROSSBACH Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 19 74 History Jeffery Stuart Rossbach All Rights Reserved THE SECRET SIX: A STUDY OF THE CONSPIRACY BEHIND JOHN BROWN'S RAID A Dissertation By JEFFERY STUART ROSSBACH Approved as to style and content by: Stephen B. Oates, Chairman of Committee Gerald W. McFarland, Member A. W. Plumsted, Member Robert H. McNeal, Chairman Department of History May 1974 The Secret Six: A Study of the Conspiracy Behind John Brown's Raid (May 1974) Jeffery Stuart Rossbach, B.A. , Providence College M.A. , Providence College Directed by: Stephen B. Oates A few days after New Year's in 1857 on a windy, bitter cold afternoon in Boston, a gaunt somber-faced man named John Brown appeared at the Bromfield Street offices of the Massachusetts Kansas Aid Committee. -

A John Brown Story 11 Louis A

The Afterlife of John Brown This page intentionally left blank The Afterlife of John Brown Edited by Andrew Taylor and Eldrid Herrington THE AFTERLIFE OF JOHN BROWN © Andrew Taylor and Eldrid Herrington, 2005. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 1–4039–6992–2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The afterlife of John Brown / edited by Andrew Taylor and Eldrid Herrington. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–4039–6992–2 1. Brown, John 1800–1859—Influence. 2. Brown, John 1800–1859— Public opinion. 3. Public opinion—United States. 4. Brown, John 1800–1859—In literature. 5. American literature—History and criticism. 6. Abolitionists—United States—Biography—Miscellanea. I. Taylor, Andrew, 1968– II. Herrington, Eldrid. E451.A33 2005 973.7Ј114—dc22 2005048677 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. First edition: December 2005 10987654321 Printed in the United States of America. -

The Civil War in Film Prof

Hist1016{25}/AS1025{25} The Civil War in Film Prof. Patrick Rael, Bowdoin College, Spring 2013 Meets: (Class) TuTh 11:30-1:00, Mass Hall McKeen Study 105 Office: 211C Hubbard (Film lab) TuTh 6:30-9:25, Mass Hall McKeen Study 105 Phone: x3775 Office hours: TuTh 2-4, by apt. [email protected] his course examines the history of the Civil War as presented in feature films. Of course, the Civil War has long captured the American imagination. In the last century, films have become perhaps the most important culture expression of popular historical consciousness. TWe will thus explore the history of the Civil War by examining film as a medium for interpreting that conflict. What was the Civil War about, and what were its consequences? How have feature films offered understandings of this central conflict in American history? How do films more generally handle historical subjects, and what does this say about their role in formulating the popular historical consciousness? How have films as history changed over time? What, in short, is the relationship between film as a pop-cultural expression and the American past? In essence, then, we are examining the history of historical interpretations — perhaps more than we are actually examining the history of the war itself. Level: This course is a first-year seminar, intended to do several things: introduce students to their subject areas, introduce students to college-level paper-writing, practice introductory skills in their discipline (in this case, history), and socialize students to the seminar experience. This last objective is important. -

Current Catalog

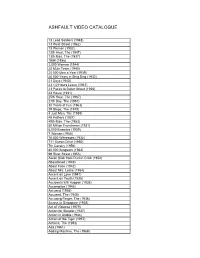

ASHFAULT VIDEO CATALOGUE 13 Lead Soldiers (1948) 13 West Street (1962) 13 Women (1932) 13th Hour, The (1947) 13th Man, The (1937) 1984 (1956) 2,000 Women (1944) 20 Mule Team (1940) 20,000 Men a Year (1939) 20,000 Years in Sing Sing (1932) 21 Days (1940) 23 1/2 Hours Leave (1937) 23 Paces to Baker Street (1956) 24 Hours (1931) 25th Hour, The (1967) 27th Day, The (1957) 30 Years of Fun (1963) 39 Steps, The (1978) 4 Just Men, The (1939) 45 Fathers (1937) 49th Man, The (1953) 50 Million Frenchmen (1931) 6,000 Enemies (1939) 7 Women (1966) 70,000 Witnesses (1932) 711 Ocean Drive (1950) 7th Cavalry (1956) 80,000 Suspects (1963) 99 River Street (1953) Aaron Slick from Punkin Crick (1952) Abandoned (1949) About Face (1942) About Mrs. Leslie (1954) Accent on Love (1941) Accent on Youth (1935) Accidents Will Happen (1938) Accomplice (1946) Accused (1936) Accused, The (1948) Accusing Finger, The (1936) Across to Singapore (1928) Act of Violence (1979) Action for Slander (1937) Action in Arabia (1944) Action of the Tiger (1957) Actress, The (1953) Ada (1961) Adding Machine, The (1969) Adorable (1933) Advance to the Rear (1964) Adventure in Baltimore (1949) Adventure in Blackmail (1942) Adventure in Diamonds (1940) Adventure in Manhattan (1936) Adventure in Washington (1941) Adventurers, The (1951) Adventures of Chico (1938) Adventures of Gerard, The (1970) Adventures of Hairbreadth Harry (1920) Adventures of Hajji Baba, The (1954) Adventures of Jane Arden, The (1939) Adventures of Kitty O'Day (1944) Adventures of Martin Eden, The (1942) Adventures -

International

INTERNATIONAL INDEX 18A WHO'S WHO 1 PICTURES 335 PROD -DISTRIBUTORS 416 STATIONS 449 SERVICES 527 COMPANIES 564 AD AGENCIES 593 GREAT BRITAIN 611 PROGRAMS 685 ORGANIZATIONS 697 CREATIVE PROGRAMMING 375 Park Ave., New York, N. Y. 10022 PLazo 1-0600 9460 Wilshire Boulevard, Beverly Hills, Calif. CRestview 4-7357 TELEVISION PRIME TIME ARNIE CBS -TV Saturday 9:00 PM BRACKEN'S WORLD NBC-TV Friday 10:00 PM JULIA NBC-TV Tuesday 8:30 PM NANNY AND THE PROFESSOR ABC-TV Friday 8:00 PM ROOM 222 ABC-TV Wednesday 8:30 PM THE GLEN FORD SHOW CBS -TV 1971-72 Season The more you know about Scotch, the more loyal you are to Ballantines. u. ,.. To , SM as yr `+yr $7.39 a fifth ,.. h FAA BLENDED SCOTCH WHISKY, BOTTLED IN SCOTLAND. 66 PROOF. IMPORTED BY" 21"BRANDS,INC.,N.Y.C. Where you expect a difference, and find it. PARAMOUNT TELEVISION A Gulf+Western Company PARAMOUNT TELEVISION SALES, INC. A Gulf+Western Company PARAMOUNT TELEVISION/A DIVISION OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES CORPORATION 5451 MARATHON STREET, HOLLYWOOD, CALIF. 90038/TEL. (213) 463.0100 RACINE presents Timers and GALLO -GALLEY Chronographs No. 810F-GALCO FILMETER TIMER 7 jewels, anti -magnetic unbreakable mainspring, hinged nickel case, easy to read dial. Sugg. Ret. $43.00 No. 815F-With button-$43.00 No. 510F-Same as above but one jewel Sugg. Retail $30.50 No. 515F-With button-$30.50 No. 9010 50 it? GALCO BROADCASTING TIMER Center register sweep facilitates -45 15- quick reading. Anti -magnetic, 7 jewels, red register hand. Dependable.