A History of Nass

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 14, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT: Matt Porter (617) 514-1574 [email protected] www.jfklibrary.org John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Essay Contest Winner Recounts Conflict over Refugees Fleeing Nazi Germany – Winning Essay Profiles Former US Representative Edith Nourse Rogers of Massachusetts – Boston, MA—The John F. Kennedy Library Foundation today announced that Elazar Cramer, a senior at the Maimonides School in Brookline, Massachusetts, has won the national John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Essay Contest for High School Students. The winning essay describes the political courage of Edith Nourse Rogers, a Republican US Representative from Massachusetts who believed it was imperative for the United States to respond to the humanitarian crisis in Nazi Germany. She defied powerful anti-immigrant groups, prevailing public opinion, and the US government’s isolationist policies to propose legislation which would increase the number of German-Jewish refugee children allowed to enter the United States. Cramer will be honored at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum on May 19, 2019, and will receive a $10,000 scholarship award. The first-place winner will also be a guest at the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation’s May Dinner at which Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, will receive the 2019 John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage Award. Pelosi is being honored for putting the national interest above her party’s interest to expand access to health care for all Americans and then, against a wave of political attacks, leading the effort to retake the majority and elect the most diverse Congress in our nation’s history. -

Blanche Kelso Bruce (1841–1898)

Blanche Kelso Bruce (1841–1898) Born into slavery in 1841, Blanche Kelso n an effort to enhance the collection with portraits of women and Bruce became the first African American to minorities who served the U.S. Senate with distinction, the Senate serve a full term in the U.S. Senate, as well as the first African American to preside Commission on Art approved the commissioning of portraits of over the Senate. One of 11 children, Bruce Blanche Kelso Bruce and Margaret Chase Smith (p. 338) in October was born near Farmville, Virginia, and was 1999. Senator Christopher Dodd, chairman of the Senate Committee taken to Mississippi and Missouri by his on Rules and Administration and a member of the Senate Commission owner. Just 20 years old when the Civil I War began, Bruce tried to enlist in the on Art, proposed the acquisition of Senator Bruce’s portrait, with the strong Union army. At that time, the army did not support of Majority Leader Tom Daschle and Republican Leader Trent accept black recruits, so instead Bruce turned to teaching; he later organized the Lott, also members of the commission. An advisory board of historians first school in Missouri for African Ameri- and curators was established to review the artists’ submissions and pro- cans. He briefly attended college in Ohio vide recommendations to the Senate Commission on Art. Washington, but left to work as a porter on a riverboat. In 1869 Bruce moved to Mississippi to D.C., artist Simmie Knox was selected in 2000 to paint Bruce’s portrait. -

Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 1 Nov-2006 Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P. Watson Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Robert P. (2006). Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 1-20. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 By Robert P. Watson1 Abstract Women have made great progress in electoral politics both in the United States and around the world, and at all levels of public office. However, although a number of women have led their countries in the modern era and a growing number of women are winning gubernatorial, senatorial, and congressional races, the United States has yet to elect a female president, nor has anyone come close. This paper considers the prospects for electing a woman president in 2008 and the challenges facing Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice–potential frontrunners from both major parties–given the historical experiences of women who pursued the nation’s highest office. -

Important Women in United States History (Through the 20Th Century) (A Very Abbreviated List)

Important Women in United States History (through the 20th century) (a very abbreviated list) 1500s & 1600s Brought settlers seeking religious freedom to Gravesend at New Lady Deborah Moody Religious freedom, leadership 1586-1659 Amsterdam (later New York). She was a respected and important community leader. Banished from Boston by Puritans in 1637, due to her views on grace. In Religious freedom of expression 1591-1643 Anne Marbury Hutchinson New York, natives killed her and all but one of her children. She saved the life of Capt. John Smith at the hands of her father, Chief Native and English amity 1595-1617 Pocahontas Powhatan. Later married the famous John Rolfe. Met royalty in England. Thought to be North America's first feminist, Brent became one of the Margaret Brent Human rights; women's suffrage 1600-1669 largest landowners in Maryland. Aided in settling land dispute; raised armed volunteer group. One of America's first poets; Bradstreet's poetry was noted for its Anne Bradstreet Poetry 1612-1672 important historic content until mid-1800s publication of Contemplations , a book of religious poems. Wife of prominent Salem, Massachusetts, citizen, Parsons was acquitted Mary Bliss Parsons Illeged witchcraft 1628-1712 of witchcraft charges in the most documented and unusual witch hunt trial in colonial history. After her capture during King Philip's War, Rowlandson wrote famous Mary Rowlandson Colonial literature 1637-1710 firsthand accounting of 17th-century Indian life and its Colonial/Indian conflicts. 1700s A Georgia woman of mixed race, she and her husband started a fur trade Trading, interpreting 1700-1765 Mary Musgrove with the Creeks. -

Review Essay

Review Essay The Highest Glass Ceiling: Women’s Quest for the American Presidency. By Ellen Fitzpatrick. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2016. 318 pp. Notes, index. Cloth, $25.95. ISBN: 978-0-674-08893-1. Reviewed by Mary A. Yeager The Highest Glass Ceiling appeared just before the 2016 election. Hillary’s ghost hovers. The U.S. presidency remains a male stronghold with its glass ceiling intact. Fitzpatrick and her publisher undoubtedly saw opportunity in a probable Clinton victory. There is a brief prologue and epilogue about Clinton that bookends the biographies of three other women who competed for the presidency in different eras: Victoria Woodhull, the Equal Rights Party candidate in 1872; Margaret Chase Smith, the 1964 Republican nominee; and Shirley Chisholm, the 1972 Democratic challenger. In selecting these four women out of the two hundred or so other women who have either “sought, been nominated, or received votes for the office of the President,” Fitzpatrick adds an American puzzle to a growing and globalizing stream of research that has tackled the question of gender in political campaigns and in business (p. 5). Why have women been so disadvantaged relative to men as political leaders and top exec- utives, perhaps more so in the democratic market-oriented United States than almost anywhere else in the world? Scholars have begun to examine how women compete for the top executive jobs and the conditions under which they are successful. They have devised contemporary experiments using a variety of decision rules to understand how gender affects women’s and men’s participation in politics. -

Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 1 Nov-2006 Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P. Watson Recommended Citation Watson, Robert P. (2006). Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 1-20. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 By Robert P. Watson1 Abstract Women have made great progress in electoral politics both in the United States and around the world, and at all levels of public office. However, although a number of women have led their countries in the modern era and a growing number of women are winning gubernatorial, senatorial, and congressional races, the United States has yet to elect a female president, nor has anyone come close. This paper considers the prospects for electing a woman president in 2008 and the challenges facing Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice–potential frontrunners from both major parties–given the historical experiences of women who pursued the nation’s highest office. -

How the History of Female Presidential Candidates Affects Political Ambition and Engagement Kaycee Babb Boise State University GIRLS JUST WANNA BE PRESIDENT

Boise State University ScholarWorks History Graduate Projects and Theses Department of History 5-1-2017 Girls Just Wanna Be President: How the History of Female Presidential Candidates Affects Political Ambition and Engagement KayCee Babb Boise State University GIRLS JUST WANNA BE PRESIDENT: HOW THE HISTORY OF FEMALE PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES AFFECTS POLITICAL AMBITION AND ENGAGEMENT by KayCee Babb A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Applied Historical Research Boise State University May 2017 © 2017 KayCee Babb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by KayCee Babb Thesis Title: Girls Just Wanna Be President: The Impact of the History of Female Presidential Candidates on Political Ambition and Engagement Date of Final Oral Examination: April 13, 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student KayCee Babb, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Jill Gill, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jaclyn Kettler, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Leslie Madsen-Brooks, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Jill Gill, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Tammi Vacha-Haase, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Jill Gill from the History Department at Boise State University. Their office door was always open for questions, but more often for the expression of stress and frustration that I had built up during these last two years. -

ED 078-451 AUTHOR TITLE DOCUMENT RESUME Weisman

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 078-451 AUTHOR Weisman, Martha TITLE Bow Women in Politics View the Role TheirSexPlays in the Impact of Their Speeches ,ontAudienees.. PUB DATE Mar 73 - - NOTE 15p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Eastern Communication Assn. (New York, March 1973) - _ - EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Communication (Thought Transfer; Females;_ Persuasive Discourse; *Political Attitudes;.Public Opinion; *Public Speaking; *Rhetorical Criticisn; *Sex Discrimination; Social Attitudes; *Speeches ABSTRACT While investigatingmaterialsfor a new course at City College of New York dealing with the rhetoric of women activists, women who were previously actively Involved in, the political scene* were asked to respoftd to the question, Does the fact that youare =awoolen affect the content, delivery, or reception of your ideas by theAudiences you haye addressed? If so, how? Women of diverse political and ethnic backgrounds replied.._Although the responses were highly subjective, many significant issues were recognized thatcallfor further investigation._While a number of women'denied that sex plays any role intheimpact of their ideas on audiences, others recognized the prejudices they face when delivering Speeches. At the same time* some women who identified the obstacles conceded that these prejudices can often be used to enhancetheir ethos. One of the-most-significant points emphasized was that we may have reached a new national. consciousness toward women politicians. _ FILMED FROM BEST AVAILABLECOPY . HOW WOMEN IN POLITICS -

Teaching Lesbian Poetry

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Women's Studies Quarterly Archives and Special Collections 1980 Teaching Lesbian Poetry Elly Bulkin How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/wsq/446 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] would value being in a class that did so, and that it would make presentation of role models of strong, self-actualizing women history much more interesting. I am encouraged by their can have a powerful , positive influence on both boys and girls. response and determined to integrate the history of women with the material presented in the traditional text. Students on the Sandra Hughes teaches sixth grade at Magnolia School in elementary school level are eager to learn about women, and the Upland, California. The list of women studied included : Jane Addams , Susan B. Anthony, Martha Berry , Elizabeth Blackwell, Mary Mcleod Bethune, Rachel Carson, Shirley Chisholm , Prudence Crandall , Marie Curie , Emily Dickinson , Emily Dunning , Amelia Earhart , Anne Hut chinson , Jenny Johnson , Helen Keller , Abby Kelley , Mary Lyon, Maria Mitchell, Deborah Moody, Lucretia Mott , Carry Nation , Annie Oakley, Eleanor Roosevelt, Sacajawea , Margaret Chase Smith, Elizabeth Cady Stanton , Harriet Beecher Stowe , Harriet Tubman, and Emma Willard . Teaching Lesbian Poetry * By Elly Bulkin In all that has been written about teaching women's literature, between nonlesbian students and lesbian material. Although I about classroom approaches and dynamics , there is almost no do think that a nonlesbian teacher should teach lesbian writing in discussion of ways to teach lesbian literature. -

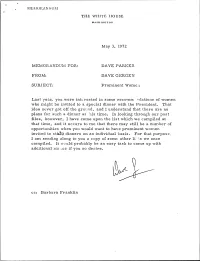

Dave Gergen to Dave Parker Re

MEf\IOR/\NIHJM THE WHITE HOUSE WASIIINGTON May 3, 1972 MEMORANDUM FOR: DAVE PARKER FROM: DAVE GERGEN SUBJECT: Prominent Wome~l Last year, you were int( rested in some recomrrj "c1ations of women who might be invited to a special dinner with the President. That idea never got off the ground, and I understand that there are no plans for such a dinner at :lis time. In looking through our past files, however, I have come upon the list which we compiled at that time, and it occurs to me that there Inay still be a number of opportunities when you would want to have prominent wom.en invited to st~~ dinners on an individual basis. For that purpose: I am sending along to you a copy of some other li i~S we once compiled. It would probably be an easy task to come up with additional nm, ~cs if you so desire. cc: Barbara Franklin r-------------------------------------------------------------- Acaflemic Hanna Arendt - Politic'al Scientist/Historian Ar iel Durant - Histor ian Gertrude Leighton - Due to pub lish a sem.ina 1 work on psychiatry and law, Bryn Mawr Katherine McBride - Retired Bryn Mawr President Business Buff Chandler - Business executive and arts patron Sylvia Porter - Syndicated financial colun1.nist Entertainment Mar ian And ",r son l Jacqueline I.. upre - British cellist Joan Gan? Cooney - President, Children1s Television Workshop; Ex(,cutive Producer of Sesaxne St., recently awarded honorary degre' fron'l Oberlin Agnes DeMille - Dance Ella Fitzgerald Margot Fonteyn - Ballerina Martha Graham. - Dance Melissa Hayden - Ballerina Helen Hayes Katherine Hepburn Jv1ahilia Jackson Mary Martin 11ary Tyler Moore Leontyne Price Martha Raye B(~verley Sills - Has appeared at "\V1-I G overnmcnt /Politics ,'. -

Gender, Fear, and Consequence in Margaret Chase Smith's "Declaration of Conscience"

Furman Humanities Review Volume 30 April 2019 Article 5 2019 The Conscience of the Cold War: Gender, Fear, and Consequence in Margaret Chase Smith's "Declaration of Conscience" Elizabeth Campbell '18 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/fhr Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Elizabeth '18 (2019) "The Conscience of the Cold War: Gender, Fear, and Consequence in Margaret Chase Smith's "Declaration of Conscience"," Furman Humanities Review: Vol. 30 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/fhr/vol30/iss1/5 This Article is made available online by Journals, part of the Furman University Scholar Exchange (FUSE). It has been accepted for inclusion in Furman Humanities Review by an authorized FUSE administrator. For terms of use, please refer to the FUSE Institutional Repository Guidelines. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CONSCIENCE OF THE COLD WAR: GE DER, FEAR,ANDCO EQUE CEI MAR ARET CHA ES ITH'S "DECLARATIO OF Co lE " Elizabeth Campbell Taking a tand On June 1, 1950, freshman Senator Margaret hase Smith, a moderate Republican from Maine, stood waiting on a DC Metro platfonn. The train that wou ld take her to the Capito l wa du any minute and she was anxious about the day ahead. Her colleague, Senator Joseph McCarthy the Re publican senator from Wisconsin, greeted her on the plat form. McCarthy noticed Smith 's uneasy demeanor and ad dressed her: 'Margare t, you look very serious. Are you going to make a speech?' ' Yes , and you will not like it "s he re plied.