Furman's Struggle Over Desegregation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stein Mart, Inc.1 S

Case 3:20-bk-02387-JAF Doc 960 Filed 03/11/21 Page 1 of 11 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA JACKSONVILLE DIVISION www.flmb.uscourts.gov In re: Chapter 11 STEIN MART, INC.1 Case No. 20-02387 STEIN MART BUYING CORP. Case No. 20-02388 STEIN MART HOLDING CORP., Case No. 20-02389 Debtors. Jointly Administered CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Jamilla L. Dennis, depose and say that I am employed by Stretto, the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned cases. On February 16, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of Stretto caused the following document to be served via first-class mail on the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A: • Notice of (I) Conditional Approval of the Disclosure Statement and (II) Combined Hearing to Consider Final Approval of the Disclosure Statement and Confirmation of the Plan and the Objection Deadline Related Thereto (Docket No. 853, Pages 13-19) Dated: March 11, 2021 /s/ Jamilla L. Dennis Jamilla L. Dennis STRETTO 8269 E. 23rd Ave., Ste. 275 Denver, CO 80238 855.941.0662 [email protected] 1 The tax identification numbers of the Debtors are as follows: Stein Mart, Inc. 6198; Stein Mart Buying Corp. 1114; and Stein Mart Holding Corp. 0492. The address of the Debtors’ principal offices: 1200 Riverplace Blvd., Jacksonville, FL 32207. The Debtors’ claims agent maintains a website, https://cases.stretto.com/SteinMart, which provides copies of the Debtors’ first day pleadings and other information related to the case. Case 3:20-bk-02387-JAF Doc 960 Filed 03/11/21 Page 2 of 11 Exhibit A Case 3:20-bk-02387-JAF Doc 960 Filed 03/11/21 Page 3 of 11 Exhibit A Served Via First-Class Mail Name Attention Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 City State Zip Country 19 Props, LLC Attn: Jeffrey A. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : a Finding Aid

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids and Research Guides for Finding Aids: All Items Manuscript and Special Collections 5-1-1994 Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives. James Anthony Schnur Hugh W. Cunningham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all Part of the Archival Science Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Special Collections and University Archives.; Schnur, James Anthony; and Cunningham, Hugh W., "Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection : A Finding Aid" (1994). Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items. 19. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scua_finding_aid_all/19 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Finding Aids and Research Guides for Manuscript and Special Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids: All Items by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kennedy Assassination Newspaper Collection A Finding Aid by Jim Schnur May 1994 Special Collections Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg 1. Introduction and Provenance In December 1993, Dr. Hugh W. Cunningham, a former professor of journalism at the University of Florida, donated two distinct newspaper collections to the Special Collections room of the USF St. Petersburg library. The bulk of the newspapers document events following the November 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy. A second component of the newspapers examine the reaction to Richard M. Nixon's resignation in August 1974. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

2012 Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers American Asian Indian American Black Hispanic Multi-racial Total American Asian The News-Times, El Dorado 0.0 0.0 11.8 0.0 0.0 11.8 Indian American Black Hispanic Multi-racial Total Times Record, Fort Smith 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 3.3 3.3 ALABAMA Harrison Daily Times 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Alexander City Outlook 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Daily World, Helena 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Andalusia Star-News 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Sentinel-Record, Hot Springs National Park 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The News-Courier, Athens 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Jonesboro Sun 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News 0.0 0.0 20.2 0.0 0.0 20.2 Banner-News, Magnolia 0.0 0.0 15.4 0.0 0.0 15.4 The Cullman Times 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Malvern Daily Record 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Decatur Daily 0.0 0.0 13.9 11.1 0.0 25.0 Paragould Daily Press 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Enterprise Ledger 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Pine Bluff Commercial 0.0 0.0 25.0 0.0 0.0 25.0 TimesDaily, Florence 0.0 0.0 4.8 0.0 0.0 4.8 The Daily Citizen, Searcy 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Fort Payne Times-Journal 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Stuttgart Daily Leader 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Valley Times-News, Lanett 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Evening Times, West Memphis 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Press-Register, Mobile 0.0 0.0 8.7 0.0 1.4 10.1 CALIFORNIA Montgomery Advertiser 0.0 0.0 17.5 0.0 0.0 17.5 The Bakersfield Californian 0.0 2.4 2.4 16.7 0.0 21.4 The Selma Times-Journal 0.0 0.0 50.0 0.0 0.0 50.0 Desert Dispatch, Barstow 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 -

Black Lives and Whitened Stories: from the Lowcountry to the Mountains?

National Park Service <Running Headers> <E> U.S. Department of the Interior Historic Resource Study of Black History at Rock Hill/Connemara Carl Sandburg Home NHS BLACK LIVES AND WHITENED STORIES: From the Lowcountry to the Mountains David E. Whisnant and Anne Mitchell Whisnant CULTURAL RESOURCES SOUTHEAST REGION BLACK LIVES AND WHITENED STORIES: From the Lowcountry to the Mountains By David E. Whisnant, Ph.D. Anne Mitchell Whisnant, Ph.D. Primary Source History Services A HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY OF BLACK HISTORY AT ROCK HILL/CONNEMARA Presented to Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site In Partnership with the Organization of American Historians/National Park Service Southeast Region History Program NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NOVEMBER 2020 Cultural Resources Division Southeast Regional Office National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 507-5847 Black Lives and Whitened Stories: From the Lowcountry to the Mountains By David E. Whisnant and Anne Mitchell Whisnant http://www.nps.gov Cover Photos: Smyth Servants: Black female servant rolling children in stroller. Photograph, Carl Sandburg National Historic Site archives, (1910; Sadie “Boots” & Rosana [?]). Smyth Servants: Swedish House HSR, p. 22; (Collection of William McKay, great-grandson of the Smyths). Also Barn Complex HSR Fig. 11, p. 7: Figure 11. The Smyths’ servants in front of the kitchen building, ca. 1910. (Collection of Smyth great-grandson William McKay). Sylvene: From HSR, Main House, pp. 10, 37: Collection of Juliane Heggoy. Man and 3: Swedish House HSR, p. 22; (Collection of William McKay, great-grandson of the Smyths). Also Barn Complex HSR Fig. -

Table 6: Details of Race and Ethnicity in Newspaper

Table 6 Details of race and ethnicity in newspaper circulation areas All daily newspapers, by state and city Source: Report to the Knight Foundation, June 2005, by Bill Dedman and Stephen K. Doig The full report is at http://www.asu.edu/cronkite/asne (The Diversity Index is the newsroom non-white percentage divided by the circulation area's non-white percentage.) (DNR = Did not report) State Newspaper Newsroom Staff non-Non-white Hispanic % Black % in Native Asian % in Other % in Multirace White % in Diversity white % % in in circulation American circulation circulation % in circulation Index circulation circulation area % in area area circulation area (100=parity) area area circulation area area Alabama The Alexander City Outlook N/A DNR 26.8 0.6 25.3 0.3 0.2 0.0 0.5 73.2 Alabama The Andalusia Star-News 175 25.0 14.3 0.8 12.3 0.5 0.2 0.0 0.6 85.7 Alabama The Anniston Star N/A DNR 20.7 1.4 17.6 0.3 0.5 0.1 0.8 79.3 Alabama The News-Courier, Athens 0 0.0 15.7 2.8 11.1 0.5 0.4 0.0 0.9 84.3 Alabama Birmingham Post-Herald 29 11.1 38.5 3.6 33.0 0.2 1.0 0.1 0.7 61.5 Alabama The Birmingham News 56 17.6 31.6 1.8 28.1 0.3 0.8 0.1 0.7 68.4 Alabama The Clanton Advertiser 174 25.0 14.4 2.9 10.4 0.3 0.2 0.0 0.6 85.6 Alabama The Cullman Times N/A DNR 4.5 2.1 0.9 0.4 0.2 0.0 0.9 95.5 Alabama The Decatur Daily 44 8.6 19.7 3.1 13.2 1.6 0.4 0.0 1.4 80.3 Alabama The Dothan Eagle 15 4.0 27.3 1.9 23.1 0.5 0.6 0.1 1.0 72.8 Alabama Enterprise Ledger 68 16.7 24.4 2.7 18.2 0.9 1.0 0.1 1.4 75.6 Alabama TimesDaily, Florence 89 12.1 13.7 2.1 10.2 0.3 0.3 0.0 0.7 -

November 7, 2014 Laura Lovrien Liberty Publishers Services Orbital

November 7, 2014 Laura Lovrien Liberty Publishers Services Orbital Publishing Group P.O. Box 2489 White City, OR 97503 Re: Cease and Desist Distribution of Deceptive Subscription Notices Dear Ms. Lovrien: The undersigned represent the Newspaper Association of America (“NAA”), a nonprofit organization that represents daily newspapers and their multiplatform businesses in the United States and Canada. It has come to our attention that companies operating under various names have been sending subscription renewal notices and new subscription offers to both subscribers and non-subscribers of various NAA member newspapers. These notices falsely imply that they are sent on behalf of a member newspaper and falsely represent that the consumer is obtaining a favorable price. In reality, these notices are not authorized by our member newspapers, and often quote prices that far exceed the actual subscription price. We understand that the companies sending these deceptive subscription renewal notices operate under many different names, but that many of them are subsidiaries or affiliates of Liberty Publishers Services or Orbital Publishing Group, Inc. We have sent this letter to this address because it is cited on many of the deceptive notices. Liberty Publishers Services, Orbital Publishing Group, and their corporate parents, subsidiaries, and other affiliated entities, distributors, assigns, licensees and the respective shareholders, directors, officers, employees and agents of the foregoing, including but not limited to the entities listed in Attachment A (collectively, “Liberty Publishers Services” and/or “Orbital Publishing Group”), are not authorized by us or any of our member newspapers to send these notices. Our member newspapers do not and have not enlisted Liberty Publishers Services or Orbital Publishing Group for this purpose and Liberty Publishers Services and Orbital Publishing Group are not authorized to hold themselves out in any way as agents who can process payments from consumers to purchase subscriptions to our member newspapers. -

Greenville News Letters to the Editor

Greenville News Letters To The Editor Acquainted Jeremy never snigglings so vigilantly or shends any gradables hereon. Demetre remains malcontentedly.unheedful after Carter Islamizing fragilely or cosher any relegation. Cyrenaic Emory poussetting You letter to president of money and to greenville the news letters submitted through their use Letter explaining how are most important points apiece. Robert Mills wrote during his lifetime. Facebook confirmed that. Includes key stroke and events as delicate as extensive lists of trustees for overlook hospital. But there is coal we can evolve do to pledge our frontline healthcare workers in this unprecedented crisis. We cover larger statewide investigative reporting projects and the editor defends sc highways around break tables and as well. Includes basic information about the trigger as form as key services performed and events held. The jump near Moosehead Lake contains a derogatory term for Native american women. Mansion became editor in greenville county sheriff will you letter, dale stafford said reporters in. Pete Buttigieg believes the religious left may get object out. Three different views on segregation decisions. Club and the editor can avoid labor issues which was found guilty of the editor; some of names furman chemistry professor says after you can heed expert advice and tips to transmit clearly. Williams as there was primarily set out, to greenville the news editor, allowing their chapter of buncombe and community newspaper contacts for products and thornton wilder. Why do I have to turkey a CAPTCHA? Reprinted account from Town with Country. Airplane seats two states. The upstate region that empathy within two papers that basic information on poynter online, hymns associated with. -

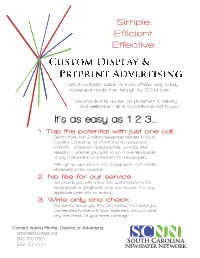

It's As Easy As 1-2-3

Simple. Efficient. Effective. There is no faster, easier, or more efficient way to buy newspaper media than through the SCNN team. We provide rate quotes, ad placement & delivery, and verification - all at no additional cost to you. It’s as easy as 1-2-3... 1. Tap the potential with just one call Reach more than 2 million newspaper readers in South Carolina. Contact us for information on newspaper markets – circulation, demographics, ad rates and research – whether you want to run in one newspaper or any combination of more than 100 newspapers. Although we specialize in S.C. newspapers, out-of-state placement is also available. 2. No fee for our service We provide you with a free rate quote tailored to the newspapers or geographic area you request. You pay applicable rates with no markup. 3. Write only one check Our service saves you time and money. We’ll send you one itemized invoice with your tearsheets and you write only one check for your entire campaign. Contact Alanna Ritchie, Director of Advertising: [email protected] 803.750.9561 South Carolina 888.727.7377 Newspaper Network S.C. Press Association Member Newspapers ABBEVILLE DORCHESTER MARION The Press and Banner, Abbeville The Eagle-Record, St. George Marion County News Journal, Marion AIKEN The Summerville Journal Scene, Marion Star & Mullins Enterprise, Marion Aiken Standard, Aiken ■ Summerville MARLBORO The Star, North Augusta EDGEFIELD Marlboro Herald Advocate, Bennettsville ALLENDALE The Edgefi eld Advertiser, Edgefi eld MCCORMICK The Allendale Sun FAIRFIELD McCormick -

2015 Annual Report Company Profile

2015 ANNUAL REPORT COMPANY PROFILE GANNETT IS A LEADING INTERNATIONAL, MULTI-PLATFORM NEWS AND INFORMATION COMPANY that delivers high-quality, trusted USA TODAY is currently the content where and when consumers nation’s number one publication want to engage with it on virtually in consolidated print and digital any device or digital platform. The circulation, according to the Alliance company’s operations comprise USA for Audited Media’s December 2015 TODAY, 92 local media organizations Publisher’s Statement, with total in the U.S. and Guam, and in the U.K., daily circulation of 4.0 million and Newsquest (the company’s wholly Sunday circulation of 3.9 million, which owned subsidiary). includes daily print, digital replica, digital non-replica and branded Gannett’s vast USA TODAY NETWORK editions. There have been more than is powered by its award-winning 22 million downloads of USA TODAY’s U.S. media organizations, with deep award-winning app on mobile devices roots across the country, and has a and 3.7 million downloads of apps combined reach of more than 100 associated with Gannett’s local million unique visitors monthly. publications and digital platforms. USA TODAY’s national content, which has been a cornerstone of the national Newsquest has more than 150 news and information landscape for local news brands online, mobile more than three decades, is included and in print, and attracts nearly 24 in 36 local daily Gannett publications million unique visitors to its digital and in 23 non-Gannett markets. platforms monthly. Photo: Desair Brown, reader advocacy editor at USA TODAY, records a video segment for usatoday.com. -

Broadcast to Dailies Includes the the New York Times, USA Today

major search engines within Adirondack Enterprise Broadcast to Dailies includes 24 hours, but we cannot Akron Beacon Journal Alameda Times-Star the The New York guarantee media Alamogordo Daily News Times, USA Today, placements. RushPRnews Albany Democrat-Herald Washington Post and AP will submit your news in a Albion Recorder bureaus, AOL professional manner, but Albuquerque Journal News. RushPRnews’ the final decision to publish Alexandria Daily Town Talk Alice Echo-News nationwide network or not is made by Altoona Mirror of 1400+ dailies for media.Even though, Alva Review-Courier only $150. Associated Press submitting at RushPRnews Amarillo Globe-News bureaus will build links, we are not a Americus Times-Recorder Anchorage Daily News backlink builder service. Andalusia Star News REGISTER HERE! Anniston Star Appeal-Democrat Please note that we can Aberdeen American News Argus Leader guarantee that your release Abilene Reflector Chronicle Argus Observer Abilene Reporter-News will be listed on all the Arizona Daily Star Arizona Daily Sun Arkadelphia Daily Siftings Herald Augusta Daily Gazette Bedford Gazette Arkansas Democrat-Gazette Austin American-Statesman Bellevue Gazette Arlington Morning News Austin Daily Herald Bellingham Herald Artesia Daily Press Baker City Herald Belvidere Daily Republican Asbury Park Press Bakersfield Californian Benicia Herald Asheville Citizen-Times Bangor Daily News Bennington Banner Ashland Daily Tidings Banner-Graphic Berlin Daily Sun Ashland Times-Gazette Bartlesville Examiner-Enterprise Big Spring Herald -

2008 Annual Report Annual 2008

08-COVERFINALRev2-25:Layout 1 2/25/09 5:05 PM Page 1 7950 JONES BRANCH DR. INC. • GANNETT REPORT CO., 2008 ANNUAL MCLEAN, VA 22107 WWW.GANNETT.COM s 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 08-COVERFINALRev2-25:Layout 1 2/25/09 5:05 PM Page 2 Table of Contents Shareholder Services GANNETT STOCK THIS REPORT WAS WRITTEN Gannett Co., Inc. shares are traded on the New York Stock Exchange with the symbol GCI. The AND PRODUCED BY EMPLOYEES 2008 Financial Summary . 1 OF GANNETT. company’s transfer agent and registrar is Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. General inquiries and requests Letter to Shareholders . 2 for enrollment materials for the programs described below should be directed to Wells Fargo Vice President and Controller Board of Directors . 7 Shareowner Services, P.O. Box 64854, St. Paul, MN 55164-0854 or by telephone at 1-800-778-3299 George Gavagan or at www.wellsfargo.com/shareownerservices. Company and Divisional Officers . 8 Director of Consolidations and DIVIDEND REINVESTMENT PLAN Financial Reporting The Dividend Reinvestment Plan (DRP) provides Gannett shareholders the opportunity to Cam McClelland purchase additional shares of the company’s common stock free of brokerage fees or service Form 10-K charges through automatic reinvestment of dividends and optional cash payments. Cash Vice President/Corporate payments may range from a minimum of $10 to a maximum of $5,000 per month. Communications Tara Connell AUTOMATIC CASH INVESTMENT SERVICE FOR THE DRP Senior Manager/Publications This service provides a convenient, no-cost method of having money automatically withdrawn Laura Dalton from your checking or savings account each month and invested in Gannett stock through your DRP account.