Exploring Mall As a Producer and Product of the Spatialisation of India’S New Middle Class Author(S): Kulwinder Kaur Source: Explorations, ISS E-Journal, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chaipoint Outlets

Sno Store Name/Location City State Address1 Chai Point , Terminal, 1 BIAL Bangalore Karnataka Bangalore International Airport Limited , Devanahali Taluka, Bangalore-560300 Plot No. 44, Electronics 2 Infosys Bangalore Karnataka City, Hosur Road, B'lore-560100 3 Jayanagar Bangalore Karnataka No.524/2, 10th Main, 33rd Cross, Jayanagar 4th Block, Bangalore - 560 011 4 Malleshwaram Bangalore Karnataka No.64, 18th Cross, Margosa Road, Malleshwaram, Bangalore - 560 055 No.A-8, Devatha Plaza, 5 Devatha Plaza Bangalore Karnataka No.131-132, Residency Road, B'lore-560025 6 Sarjapur Bangalore Karnataka No. 38/2, Ground Floor, Kaikondrahalli village, Varthur Hobli, Bangalore East Opp to Adigas hotel, MG Road , 7 Trinity Metro Bangalore Karnataka Next to Axis Bank, Bangalore 8 DLF Cyber Hub Gurugram Delhi NCR K5, Cyber hub, Cyber City, DLF Phase 3, Gurgaon 9 Huda City Centre Gurugram Delhi NCR Huda City Centre Metro Station, Sector 29, Gurgaon, HR 122009 Near Electronics City Bommasandra village 10 Narayana Healthcare Bangalore Karnataka Bangalore Mantri commercio Kariyammana Ahgrahara , Bellendur,Bangalore-560103 11 Mantri Commercio Bangalore Karnataka Near Sakara Hospital Bangalore 12 RMZ Infinity Bangalore Karnataka Old Madras Road, Bennigana Halli, Bangalore, Karnataka 560016 S No 50, Little Plaza, Cunningham Rd, Vasanth Nagar, 13 Cunningham Road Bangalore Karnataka Bangalore, Karnataka 560002 Chai point #77 Town Building No,3 Divya shree building Yamalur post 14 77 Town Bangalore Karnataka Bangalore -37 NH Cardio center NH Health city -258/a Ground floor, Bommasandra Industrial area, 15 NH Cardio Bangalore Karnataka Bangalore, Karnataka 16 Unitech Infospace Gurugram Delhi NCR Store No 6, Unitech Infospace SEZ Sector-21, Gurgaon 17 Salarpuria Softzone Bangalore Karnataka Salarpuria Softzone ,Outer ring road ,Near sarjapur junction ,Bangalore -43 John F. -

Oct-Dec 2018

OCT-dec 2018 GET THAT PERFECT New Year PARTY LOOK getaways EFFORTLESS MAKEUP SEXY HAIRDOS DELICATE BAUBLES Must-haves for TOWERING HEELS your travel kit ALL THAT GLITTERS! FASHION’S OLD FLAME IS BACK! Winter wardrobe on point Lip-smacking TRENDS TO munchies transform your closet BON APPÉTIT Editor’s notE Dear Shoppers, It’s that time of the year again when the festive spirit reigns. As the pleasant autumn wind blows, we get ready for the upcoming season of weddings, festivals and parties. And we have already set the ball rolling at our malls, starting with weddings: we organised a grand fashion extravaganza to make sure there’s nothing amiss on your D Day! From clothes to accessories and the latest in jewellery, we collated the best our malls have to offer under one roof. A wedding or not, being glamorous is your fashion rule this season, as fashion brands present bright colours, ruffles, bling in accessories and shimmer everywhere. From sequinned ensembles to crystal-studded heels and from beaded clutches to liquid gold lips, this fall-winter, it’s all about being a diva! Ms Pushpa Bector, EVP & Head, DLF Shopping Malls, with her team For your Diwali look, turn the pages for some elegant Indo-Western inspiration. The saree goes fusion chic, draped over a pair of tights; EDITOR and the lehenga gets a crinkled makeover. Be inspired by our New Year Pushpa Bector EVP & Head, DLF Shopping Malls and Christmas party looks as well, with metallic dresses, suave velvet pantsuits and some smart ideas for the debonair man. -

Region State City Store Name West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Bandra West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Juhu West Maharashtra Mumbai

Region State City Store Name West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Bandra West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Juhu West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Kandivali West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Lower Parel West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Oberoi Mall West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Prabhadevi West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Infinity Malad West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Belapur West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma Borivali West Maharashtra Mumbai Croma R City Mall West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Chakala, Andheri West Maharashtra Mumbai Reliance Digital - Vashi West Maharashtra Mumbai Reliance Digital - Malad West Maharashtra Mumbai Reliance Digital - Viviana Mall West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Andheri West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Borivali West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Chembur West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Ghodbunder West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Hub Mall West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Opera House West Maharashtra Mumbai Vijay Sales Prabhadevi West Maharashtra Mumbai Hometown West Maharashtra Pune Croma Aundh West Maharashtra Pune Vijay Sales Pune Station West Maharashtra Pune Vijay Sales Pune Baner West Maharashtra Pune Vijay Sales Pune Chinchvad North Delhi Delhi Croma - City Walk Saket North Delhi Delhi Croma - Rajouri North Delhi Delhi Croma Dwarka North Delhi Delhi Croma Janakpuri North Delhi Delhi Croma South Ex North Delhi Delhi Homestop - Select City, Saket North Delhi Delhi Vijay Sales - Janakpuri North Delhi Delhi Vijay Sales - Lajpat Nagar North Delhi Delhi Vijay Sales - Rajouri North Uttar Pradesh Ghaziabad Reliance shipra mall -

(India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACC SELECT CITY DELHI 15017 Sele

MerchantName ShopName SHOPCODE Address State City ShopEmail Select City Walk Mall, G-16 (B), District Centre Saket, Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACC SELECT CITY DELHI 15017 New Delhi:-110017 DELHI NEW DELHI [email protected] Unit No 11 A Ground Floor ,Sky zone Building , Phoenix High Street Mall, S.B. Road, Lower Parel ( West ), Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACCPALLADIUMMUMBAI 15011 Mumbai 400014 MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI [email protected] G-4,Inorbit Shopping Mall,New Link Road,Malad (W), Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACC INORBIT MUMBAI 15007 Mumbai-400064 MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI [email protected] PACIFIC MALL COMMUNITY CENTER, G-26, NAJAFGHAR ROAD, METRO PILLAR NO. - 464 KHAYALA, NEW DELHI- Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACCPACIFIC DELHI 15010 100015 DELHI NEW DELHI [email protected] PHOENIX MARKET CITY MALL, L.B.S ROAD, KAMANI, Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACCMARKET CITYMUMBAI 15012 KURLA (W), MUMBAI-400070 MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI [email protected] Pavilion Mall, Ground Floor Shop No. G15A,Kailash Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACCPAVILLIONLUDHIANA 15024 Cinema Road, Civil Lines, Ludhiana - 141001 PUNJAB LUDHIANA [email protected] Phoenix Market City Mall,Nr.Maruti Showroom, Nagar Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACCMARKET CITYPUNE 15013 Road, Vitman Nagar Corner,PUNE-411014 MAHARASHTRA PUNE [email protected] DLF- MALL OF INDIA, SHOP NO F-169/170, PLOT NO,M- Major Brands (India) Pvt. Ltd. ALDO ACCDLF MALL OF INDIADELHI 15025 03 SECTOR -18, NOIDA UTTAR PRADESH-201301 UTTAR PRADESH NOIDA [email protected] Aldo Accessories, Store No. F-27, First Floor,Inorbit Major Brands (India) Pvt. -

S.No Shop Address 1 BB-GEN NEXT

S.No Shop Address BB-GEN NEXT-HYDERABAD-PUNJAGUTTA, SY NO. BB-GEN NEXT-HYDERABAD- 1/1,1/2,3/2,6/1 & 6/2,WARD NO 89,L&T MALL,PUNJAGUTTA X PUNJAGUTTA 1 ROADS,HYDERABAD-CENTRAL ZONE,TELANGANA. BB-GEN NEXT-HYDERABAD-MADHAPUR K.RAHEJA IT BB-GEN NEXT-HYDERABAD- PARK,INORBIT MALL,MINDSPACE,SURVEY NO.64, APIIC S/W MADHAPUR 2 UNIT LAYOUT,HTECHCITY,MADHAPUR HYDERABAD BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI- MULUND-LBS MARG-R-MALL, OPP. BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI- MULUND- RICHARDSON CRUDDAS FACTORY, LBS MARG, NEAR MULUND LBS MARG- R- MALL 3 CHECK NAKA, MULUND (WEST), MUMBAI ,MAHARASHTRA BB-GEN NEXT-THANE(WEST), HIGH STREET MALL, BB-GEN NEXT-THANE-HIGH STREET KAPURBAWDI JUNCTION, GHODBUNDER ROAD, THANE MALL 4 (WEST) ,MAHARASHTRA BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI- GHATKOPAR, R-CITY MALL ,RUNWAL BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI- GHATKOPAR- TOWN CENTRE, OPP PRESIDENTIAL TOWERS, NEAR DAMODAR R-CITY MALL 5 PARK, LBS MARG, GHATKOPAR (W) MUMBAI,MAHARASHTRA BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI-MALAD- BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI-MALAD-INFINITY MALL, MALAD LINK 6 INFINITY MALL ROAD,NEAR D-MART, MALAD(W) MUMBAI, MAHARASHTRA BB-GEN NEXT-NAVI MUMBAI- BB GEN NXT, GRAND CENTRAL, LOWER GROUND 134, PLOT 7 SEAWOOD R1, SECTOR 40, SEAWOOD RAILWAY STATION, NAVI MUMBAI BB-GEN NEXT-NAVI MUMBAI-INORBIT MALLS LOWER BB-GEN NEXT-NAVI MUMBAI-INORBIT GRD&GRD IST,INORBIT MALL,SECTOR 30 A NEXT TO CENTRE MALLS 8 ONE MALL,PALM BEACH RD, VASHI, NAVI MUMBAI BB-GEN NEXT-THANE-VIVA CITY MALL VIVA CITY MALL BB-GEN NEXT-THANE-VIVA CITY MALL (VIVIANA),NEXT TO JUPITER HOSPITAL, EASTERN EXPRESS 9 HIGHWAY, THANE BB-GEN NEXT-MUMBAI-ATRIA MALL, ATRIA MALL, DR. -

Exceptional Malls, Innovative Retail Developments Honoured at IMAGES Shopping Centre Awards 2019 by Shopping Centre News Bureau

40 May 2019 [AWARDS] Exceptional Malls, Innovative Retail Developments Honoured at IMAGES Shopping Centre Awards 2019 By Shopping Centre News Bureau Supported By Cheer Partner critical ingredients for attracting Nomination Process and jury panel, which comprised of footfalls into retail developments. The Jury distinguished personalities in the Meanwhile, style, variety, and ISCA 2019 annual awards were fi eld of research and consulting esponding to burgeoning overall quality of malls play are adjudged in two categories, with thorough insights in to the consumerism in India, crucial in ensuring customer Non-Presentation Category and business, India’s top retailers mall developers have satisfaction. Live Presentation Category. – gave score based on their rapidly started infusing This dramatically changing For the Non- presentation assessment of the nominees Rnew retail developments across the retail scenario is bringing the categories malls submitted which ultimately decided the the top seven cities, with nearly mall culture closer to shoppers of nominations, which was checked winner in each category. 10 million sq. ft. new mall over 100 cities in India. by the ISCA audit team for For the Live presentation supply in 2019, according to an IMAGES Shopping Centre eligibility, completeness and category, shopping centres mall ANAROCK report. Factoring Awards 2019 found out who data correctness. ISCA team of nominees were asked to make in the rollover of some supply the giants of the mall industry analysts then made a presentation live presentations to ‘On Ground from 2018, there will be a three- are — those who upped the ante for the ISCA prelim jury – Jury’ comprising retail real fold jump in 2019 against the and many an eyebrow in 2018; with analysis of performance estate experts from leading IPCs preceding year, says the study. -

Street District City State DB MALL, G50/51,OPP. MP NAGAR on KHASRA 1511&1509,ARERA HILLS BHOPAL MP & CG DD MALL SHOP

Street District City State DB MALL, G50/51,OPP. MP NAGAR ON KHASRA 1511&1509,ARERA HILLS BHOPAL MP & CG DD MALL SHOP NO. F-3 , FIRST FLOOR, GWALIOR MP & CG 13&14,COSMO COLONY,AMRAPALI UNIQUE ASPIRE, SHOP 3 & 4, PLOT NR. MARG, JAIPUR RAJASTHAN CITY MALL, SHOP NO. G15, JHALAWAR ROAD KOTA RAJASTHAN NO.480/1, SITUATED AT 1ST BLOCK, 3RD STAGE, BASHESHWAR NAGAR, BANGALORE KARNATAKA PHOENIX MARKET CITY,S-35, MAHADEVPUR,EAST BANGALORE KARNATAKA CITY CENTRE MALL, NO-UG-14A, UPPER GROUND FLOOR, K S RAO ROAD MANGALORE KARNATAKA NAGAR MALL OF MYSORE,SHOP GF08,INDIRA EXT.,NAZARABAD,MOHALLA,M.G.RD MYSORE KARNATAKA SAMPATH VINAYAK TEMPLE VAISHNAVI ENTERPR.,10-1-41/1, RD,SIRIPURAM VISAKHAPATNAM ANDHRA PRADESH VCC MALL, SHOP NO. 14 &15, G/F, S.P. MARG, CIVIL LINES, ALLAHABAD UP & UK FUN REPUBLIC MALL SHOP NO. 102, GOMTI NAGAR LUCKNOW UP & UK 11, MG MARG, HAZRATGANJ, HALWASIA MARKET, LUCKNOW UP & UK PHOENIX MALL, SHOP NO. 2&3,PLOT NO. CP-8,SECTOR B, KANPUR ROAD LUCKNOW UP & UK JHV MALL,SHOP NO. 12 (blank) VARANASI UP & UK AMPA SKYWALK MALL,8,G/FL.,1, NELSON MANICKAM ROAD, CHENNAI (MADRAS) TAMIL NADU UNION STORE 117-A, GRND AND FIRST FLOOR,THE MALL AMRITSAR UPPER NORTH HOP NO.1, PATRAKARPURAM CHAURAHA, GOMTI NAGAR, LUCKNOW UP & UK SOBHA MALL, UNIT NO GS-6, GR. FL. SOBHA CITY,PUZHAKKAL, THRISSUR KERALA D. N. SINGH ROAD, KHALIFA BAGH CHOWK, NEAR SBI CITY BRANCH BHAGALPUR BIHAR & JHARKHAND MARDA COMPLEX, PANI TANKI MORE, SEVOKE ROAD, SILIGURI WEST BENGAL SANTOSH PLAZA, PLOT NO. -

Store Locations

Store Locations City Store Name Locality Ahemdabad Law Garden Cross Words Ahemdabad Prahalad nagar Toy Zapp/Toy Cra Ahemdabad CG Road Kavita Toys Ahmedabad Hamleys ALPHA ONE AHMEDABAD Ahmedabad Landmark Abhijeet V AHM Law Garden Ahmedabad Shoppers Stop ALPHA AHMEDABAD Ahmedabad Shoppers Stop CG ROAD AHMEDABAD Amritsar Hamleys MALL OF AMRITSAR Amritsar Shoppers Stop AMRITSAR Aurangabad Shoppers Stop AURANGABAD Bangalore ToysRus Toys R us, Phoenix Marketcity, Bangalore Bangalore ToysRus Toys R us, Vegacity, Bangalore Bangalore Hamleys PHOENIX MARKET CITY BANGALORE Bangalore Hamleys LIDO 1MG ROAD MALL BANGALORE Bangalore Landmark Brigade Orion Mall Bangalore Bangalore ToysRus Phoenix Marketcity Bangalore Landmark Forum Mall BNG Koramangala Bangalore Hamleys MANTRI-MALL-BANGALORE Bangalore ToysRus Vegacity Bangalore Hamleys VR MALL BANGALORE Bangalore Shoppers Stop BENRGATTA Bangalore Shoppers Stop WHITEFIELD INORBIT BNG Bangalore Shoppers Stop SOUL SPACE BANGALORE Bangalore Shoppers Stop GARUDA Bangalore Landmark CMJ BLDG BNG Kamraj Road Bangalore Shoppers Stop MANTRI MALLESWARAM Bangalore Shoppers Stop OLD MADRAS BNG Bangalore Shoppers Stop KORAMANGALA Bangalore Shoppers Stop WHITEFIELD Bangalore Banshri Evergreen Toys Bangalore Bllundre Peekaboo / Baby Desire Bangalore HSR layout Kids Giggle / Baby Desire / Baby Outlet Bangalore Commercial Street Toy World Bangalore Frazer Town Dream World Bangalore HBR Layout Toy Junction Bhopal Hamleys DB CITY MALL BHOPAL Bhopal Shoppers Stop BHOPAL Bhubaneshwar Hamleys ESPLANADEONE-OD-BBR Chandigarh -

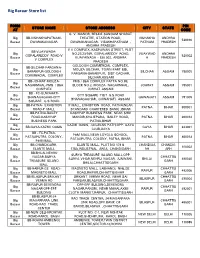

Big Bazaar Store List

Big Bazaar Store list FORM PIN STORE NAME STORE ADDRESS CITY STATE AT CODE G. V. MANOR, BESIDE SANGAM SHARAT Big BB-VISHAKHAPATNAM- THEATRE, STATION ROAD, VISHAKHA ANDHRA 530016 Bazaar DWARAKANAGAR DWARAKANAGAR, VISAKHAPATNAM , PATNAM PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH V V COMPLEX, KASPAWAN STREET, PLOT BB-VIJAYWADA- Big NO.27/23/169, GOPALAREDDY ROAD, VIJAYWAD ANDHRA GOPALAREDDY ROAD-V 520002 Bazaar VIJAYAWADA - 520 002, ANDHRA A PRADESH V COMPLEX PRADESH GOLDOGH COMMERCIAL COMPLEX, BB-SILCHAR-PARGANA- Big MOUZA SILCHAR, TOWN PART II(B), BARAKPUR-GOLDOGH SILCHAR ASSAM 788005 Bazaar PARGANA-BARAKPUR, DIST-CACHAR, COMMERCIAL COMPLEX SILCHAR,ASSAM BB-JOHRAT-MOUZA- PMS / B&A COMPLEX PATTA NO.99, Big NAGARMHAL-PMS / B&A BLOCK NO.2, MOUZA- NAGARMHAL, JOHRAT ASSAM 785001 Bazaar COMPLEX JORHAT ASSAM BB - FC-GUWAHATI- Big CITY SQUARE 118/1 G.S ROAD BHANAGAGHAR-CITY GUWAHATI ASSAM 781005 Bazaar BHANAGAGHAR, GUWAHATI, ASSAM SQUARE G.S ROAD Big BB-PATNA- EXHIBITION P MALL, EXHIBITION ROAD, PATNA(NEAR PATNA BIHAR 800001 Bazaar ROAD-P MALL STANDARD CHARTERED BANK) ,BIHAR BB-PATNA-BAILEY KASHYAP BUSINESS PARK, NEAR SHIV Big ROAD-KASHYAP MANDIR,KHAJEPURA, BAILEY ROAD, PATNA BIHAR 800014 Bazaar BUSINESS PARK PATNA,BIHAR Big KAZMI OASIS, JAGJIVAN PATH,OPP. GAYA BB-GAYA-KAZMI OASIS GAYA BIHAR 823001 Bazaar CLUB,GAYA BB - FC-PATNA- Big P&M MALL,NEAR LOYOLA SCHOOL, PATALIPUTRA COLONY- PATNA BIHAR 800013 Bazaar PATALIPUTRA COLONY, PATNA, BIHAR P&M MALL Big BB-CHANDIGARH- ELANTE MALL, PLOT NO 178 & CHANDIGA CHANDIG 160002 Bazaar ELANTE MALL 178A,INDUSTRIAL AREA, CHANDIGARH -

Spec Rest List1 Revised

HSBC S.No ty Store Name Address 1 EL-Palladium Phoenix Estee Lauder. Palladium, The Phoenix Mills Ltd. , Phoenix Mills compound, 462, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai – 400013 Estee Lauder . 1/2, Star Centre, 1 MG Mall, Swami Vivekananda 2 EL-1 MG Blr Road, Swami Vivekananda Road,Bangalore 560 008 Phoenix Market City, Velachery Main Road, Velachery, 3 EL-Market City Chennai Chennai - 600 042 Estee Lauder. Select City Walk Mall, District Center Saket, 4 EL- Saket Select CityWalk New Delhi – 110 017. 5 EL-Ambi Gurgaon Ambience Mall, Ground Floor, NH-8 , Gurgaon, Delhi- 122001. Estee lauder Quest mall, Shop no 120, first floor, 33 Syed Amir Ali 6 EL Quest Kol Avenue, Kolkata – 700 017. Unit no. S 15,Palladium, The Phoenix Mills Ltd. , Phoenix Mills 7 Bobbi Brown, Palladium compound, 462, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai – 400013 Unit Nos. G 16 and G 17 (part), Inorbit, Ground floor, Link Road, 8 BBobbi Brown Inorbit Malad Malad (west), Mumbai 400 064 Bobbi Brown - Phoenix Bobbi Brown (Shoppers Stop) Unit no. UG-16, Phoenix MarketCity 9 Marketcity Kurla mall, L.B.S. Marg, Kurla West, Mumbai, Maharashtra 400070 Unit no. UG-29, Upper ground floor,Phoenix MarketCity Mall,Pune 10 Bobbi Brown Marketcity Pune Maharashtra 411014 Shoppers Stop Ltd, (Bobbi Brown)Garuda Mall, Magrath Road, 11 Bobbi Brown Garuda Ashok Nagar, Bangalore-560 025 BOBBI BROWN, UG-06 ,Phoenix Marketcity Whitefield Main Road, 12 Bobbi Brown Phoenix City Banglore Mahadevpura, Bengaluru,Karnataka 560048. Express Avenue Mall,S0356 No. 2 , Club House Road, 13 Bobbi Brown Chennai Royapettah, Chennai,Tamil Nadu 600002 BobbiBrown,Shop no.UG 22,Nelson Mandel road,Vasant Kunj 14 Bobbi Brown,Vasant Kunj New Delhi 110070 Shop no. -

Shop Name Outlet Address City State Charles

Shop Name Outlet Address City State Charles & KeithSELECT CITYWALK G-69, SELECT CITY WALK MALL, A-3, DISTRICT CENTRE, SAKET,NEW DELHI - 110017 DELHI New Delhi Charles & KeithPROMENADE MALL SHOP NO 163-164,DLF PROMENADE MALL, VASANT KUNJ, DELHI -110070 DELHI New Delhi Charles & KeithPACIFIC MALL GF 18, PACIFIC MALL COMMUNITY CENTER, NAJAFGARH ROAD, METRO PILLAR NO - 464 KHAYALA,NEW DELHI- 110018 DELHI New Delhi Charles & KeithAMBIENCE AMBI MALL F 151, VILLAGE NATHUPOOR, GURGOAN,HARYANA 122002 GURGAON Haryana Charles & KeithMALL OF INDIA Shop No. B-111/112, Plot No. M-03, Sector-18, DLF Mall of India, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201301 NOIDA U.P Charles & KeithPAVILION Store nos G-14,Bharti pavillion mall,Old session court,Near fountains chock,Ludhiana,Punjab 141001 LUDHIANA Punjab Charles & KeithWTP Store No G-25/26, A-Block, World Trade Park Mall, JLN Marg, Malvia Nagar, Jaipur-302017 JAIPUR Rajasthan Charles & KeithELANTE Ground floor -017, Elante Mall, 178-178A, Industrial & Business Park,Phase-1,Chandigarh - 160002 CHANDIGARAH Chandigarh Charles & KeithAHEMDABAD ONE G-22 ground floor, alpha one mall, near vastrapur lake,Ahmedabad-380009 AHMEDABAD Gujarat Charles & KeithGULMOHOR SHOP NO 12, GROUND FLOOR, GULMOHAR PARK,NEXT TO FUN REPUBLIC CINEMAS,SATELLITE ROAD,AHMEDABAD.- 380015. AHMEDABAD Gujarat Charles & KeithMARKET CITY PHOENIX MARKET CITY MALL, MAHADEVPURA POST,NEAR MARUTI SHOWROOM,Shop # UG 51/52, WHITEFIELD ROAD,BANGALORE-48 BANGALORE Karnataka Charles & KeithPALLADIUM 462, S.B. ROAD,UNIT NO.13,GRAND GALLERIA, PHOENIX MALL,GROUND FLOOR,LOWER PAREL,MUMBAI - 400013 MUMBAI Maharashtra Charles & KeithINFINITI SHOP NO G-035, INFINITI MALL, GROUND FLOOR, NEXT TO CROMA, LINK ROAD, MUMBAI - 400064 MUMBAI Maharashtra Charles & KeithLINKING ROAD VATSALA, Opp. -

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR) Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | NCR | 2019 0 The National Capital Region (NCR) in India comprises the National Capital Territory (Delhi), and some of the urban areas of its neighbouring states of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan. However, only Delhi, Gurugram and Noida are considered as the prominent real estate markets of NCR. Delhi as the capital and seat of the national government has always been home to many multinational corporations and national business houses who set up their regional and local headquarters here. Gradually, with development expanding beyond the city limits into adjacent cities, new employment and residential hubs have been created in these areas. Greater employment opportunities also led to higher in-migration creating a strong demand and consumption pool for goods and services in NCR. Additionally, being a city with immense historical, architectural and tourist attractions, Delhi pulls in a huge number of domestic and international tourists. The growth in the local and the transient population of the city and rising income and prosperity levels have had a positive impact on the retail landscape, with emergence of mall strips, large-format retail malls and emergence of new high streets along with rebirth of the conventional high streets which were primarily centred in Delhi. NCR FACTS ABOUT CITY 18.9 million - Metropolitan Population (includes Delhi, OVERVIEW Gurugram and Noida as per Census 2011) 835,000 - Average monthly foreign tourist arrivals in Delhi in 2017 (Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Tourism) $4700 Per Capita Income in Delhi (Delhi Statistical Abstract, 2016) Cushman & Wakefield | NCR | 2019 1 NCR KEY RETAIL STREETS & AREAS KHAN MARKET Khan Market is among the most prime main streets in BASANT LOK Delhi and is the most expensive in the country.