Dimitrije O. Golemović* WAS MOKRANJAC the FIRST

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Booklet

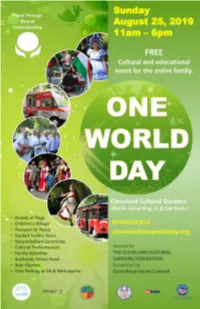

The Irish Garden Club Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians Murphy Irish Arts Association Proud Sponsors of the Irish Cultural Garden Celebrate One World Day 2019 Italian Cultural Garden CUYAHOGA COMMUNITY COLLEGE (TRI-C®) SALUTES CLEVELAND CULTURAL GARDENS FEDERATION’S ONE WORLD DAY 2019 PEACE THROUGH MUTUAL UNDERSTANDING THANK YOU for 74 years celebrating Cleveland’s history and ethnic diversity The Italian Cultural Garden was dedicated in 1930 “as tri-c.edu a symbol of Italian culture to American democracy.” 216-987-6000 Love of Beauty is Taste - The Creation of Beauty is Art 19-0830 216-916-7780 • 990 East Blvd. Cleveland, OH 44108 The Ukrainian Cultural Garden with the support of Cleveland Selfreliance Federal Credit Union celebrates 28 years of Ukrainian independence and One World Day 2019 CZECH CULTURAL GARDEN 880 East Blvd. - south of St. Clair The Czech Garden is now sponsored by The Garden features many statues including composers Dvorak and Smetana, bishop and Sokol Greater educator Komensky – known as the “father of Cleveland modern education”, and statue of T.G. Masaryk founder and first president of Czechoslovakia. The More information at statues were made by Frank Jirouch, a Cleveland czechculturalgarden born sculptor of Czech descent. Many thanks to the Victor Ptak family for financial support! .webs.com DANK—Cleveland & The German Garden Cultural Foundation of Cleveland Welcome all of the One World Day visitors to the German Garden of the Cleveland Cultural Gardens The German American National congress, also known as DANK (Deutsch Amerikan- ischer National Kongress), is the largest organization of Americans of Germanic descent. -

At the Margins of the Habsburg Civilizing Mission 25

i CEU Press Studies in the History of Medicine Volume XIII Series Editor:5 Marius Turda Published in the series: Svetla Baloutzova Demography and Nation Social Legislation and Population Policy in Bulgaria, 1918–1944 C Christian Promitzer · Sevasti Trubeta · Marius Turda, eds. Health, Hygiene and Eugenics in Southeastern Europe to 1945 C Francesco Cassata Building the New Man Eugenics, Racial Science and Genetics in Twentieth-Century Italy C Rachel E. Boaz In Search of “Aryan Blood” Serology in Interwar and National Socialist Germany C Richard Cleminson Catholicism, Race and Empire Eugenics in Portugal, 1900–1950 C Maria Zarimis Darwin’s Footprint Cultural Perspectives on Evolution in Greece (1880–1930s) C Tudor Georgescu The Eugenic Fortress The Transylvanian Saxon Experiment in Interwar Romania C Katherina Gardikas Landscapes of Disease Malaria in Modern Greece C Heike Karge · Friederike Kind-Kovács · Sara Bernasconi From the Midwife’s Bag to the Patient’s File Public Health in Eastern Europe C Gregory Sullivan Regenerating Japan Organicism, Modernism and National Destiny in Oka Asajirō’s Evolution and Human Life C Constantin Bărbulescu Physicians, Peasants, and Modern Medicine Imagining Rurality in Romania, 1860–1910 C Vassiliki Theodorou · Despina Karakatsani Strengthening Young Bodies, Building the Nation A Social History of Child Health and Welfare in Greece (1890–1940) C Making Muslim Women European Voluntary Associations, Gender and Islam in Post-Ottoman Bosnia and Yugoslavia (1878–1941) Fabio Giomi Central European University Press Budapest—New York iii © 2021 Fabio Giomi Published in 2021 by Central European University Press Nádor utca 9, H-1051 Budapest, Hungary Tel: +36-1-327-3138 or 327-3000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ceupress.com An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched (KU). -

VASE Studio Portrait of Composer Stevan Mokranjac

VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1492 Studio portrait of composer Stevan Mokranjac Object: Studio portrait of composer Stevan Mokranjac Description: Half-length frontal shot of a seated man. He is wearing a dark suit, glasses and many insignia of honor. Comment: Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac (1856, Negotin – 1914, Skopje) was a Serbian composer and music educator. His work was essential in terms of recording and organizing Valach Serbian folk poetry, which only existed in the oral tradition and can be regarded as representative of the contemporary Serbian national spirit at large. In 1899 he founded the first independent music school in Serbia with Stanislav Binički and Cvetko Manojlović: Studio portrait of composer Stevan the Serbian Music School in Belgrade. Mokranjac This photograph was the model for the © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia portrait which is printed on the current 50 Dinar banknote. Relations: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1495 Location: Belgrade Country: Serbia Type: Postcard Creator: Jovanović, Milan, (Photographer) Publisher: S.B. Cvijanović Dimensions: Artefact: 137mm x 86mm Format: Not specified Technique: Not specified Keywords: 180 Total Culture > 184 Cultural Participation 340 Structures > 344 Public Structures 450 Finance > 453 Banking 530 Arts > 533 Music 540 Commercialized Entertainment > 545 Musical Studio portrait of composer Stevan and Theatrical Productions Mokranjac 550 Individuation and Mobility > 551 Personal © Museum of Theater Art of Serbia Names 550 Individuation and Mobility > 554 Status, Role, and Prestige 560 Social Stratification https://gams.uni-graz.at/vase 1 VASE Visual Archive Southeastern Europe Permalink: https://gams.uni-graz.at/o:vase.1492 Copyright: Muzej Pozorišne Umetnosti Srbije Archive: Museum of Theater Art of Serbia, Inv. -

Searchable PDF Format

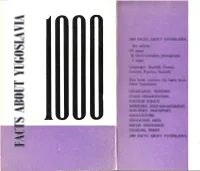

- !-l t(xt0 trA(i'l's Atr()U'I' YUGOSLAVIA (t) 4tlr eclitiorr a-\ l2tl pagcs rl -30 lrltck.unrl-wlriIc photographs - 3 rrraps - Lurrgrr:tgt's: tinglish, French, -) (icrrnitn, I\rssian, Spanish 'l'lris b<xrk c:ontuins the basic facts E- llrorrt Yrrgttslavia GT]o(;I{APIIY, I{ISTORY, r-\ w-) S ATF, OR.GANIZATION, AA IIOREIGN POLICY, WORKTJRS' SELF-MANAGEMENT, -t INDT]STRY, TRANSPORT, ACRICULTURE, a EDUCATION, ARTS, E- SOCIAL INSURANCE, (J TOURISM, SPORT IOOO FACTS ABOUT YUGOST.AVIA r= O waRszAwA .^*-h-;; c_-?6 =i PUBLISHER IZDAVACKI ZAVOD "IUGOSLAVI.I A. Beograd, Nemamjiaa 34 FACTS ABOUT YI]GOSIAYIA COUNTRY AND POPULATION GEOGRAPHIC AREA POSITION The Social srt Federral Rerpub,lic of y,urgoslavia lies, u,ith its greater part (g0 percent) in the Balkan peninsula, Southeast Europe, and, with a smaller part (20 percent) in Central Europe. Since its southwestern ,regions occupy a long length of the Adriati,c coastal be1t, it is b,oth a continental and a maritime country. The country,s extreme points extend from 40o 57' to 460 53, N. lat. and from 13" 23' to 23o 02' E. l"ong. It is consequently pole, closer to the Equator than to the North and and Italy. it has the Central European Standard time. POPULATION AND BOUNDARIES ITS NATIONAL STRUCTURE Yugoslavia is bounded by several states and the sea. On the land side, it borders on seven states: Austria and Hungary on the north, Rumania on the northeast, Bulgaria on the east, Greece on the south, Albania on the southwest and Italy on the northwest. -

CSR Projects Education

PARTNERSHIP & COMMUNITY CSR projects Education The professional association “The Ambassadors of sustainable development and environment“, a national operator of the program Young Ecoreporters, supported by the Electric Power Industry of Serbia, organizes a competition called “Energy Efficiency in view of Young Ecoreporters“ for young people 11 to 21 years old. From their own point of view, ecoreporters are to deal with is- sues related to reduction of energy consumption in their reports, which would be in a form of an essay in writing, photo or video. The young are encouraged to deal with issues on how to use energy more efficiently, how to have better quality of life, and how to pay less at the school level or in their households. The international program Young Ecoreporters is aimed at training the young how to take a stand and to report on local issues and problems in the environ- ment. The program offers to young enthusiasts a possibility for their voice to be heard because the best papers will be promoted both on local and interna- tional level. The program has been implemented for more than 20 years and YOUNG at the moment, 35 countries, where national competitions are organized, take part in it and the winner papers are sent to international competitions. The ECO- competitions are organized every year in order to encourage the young from all over the world to improve themselves, learn and investigate and to imply to environmental problems in order to motivate a local community to solve REPORTERS these. The final goal is to take initiatives for solving the global environmental problems by solving the local problems. -

Kosta P. Manojlović (1890–1949) and the Idea of Slavic and Balkan Cultural Unification

KOSTA P. MANOJLOVIĆ (1890–1949) AND THE IDEA OF SLAVIC AND BALKAN CULTURAL UNIFICATION edited by Vesna Peno, Ivana Vesić, Aleksandar Vasić SLAVIC AND BALKANSLAVIC CULTURAL UNIFICATION KOSTA P. MANOJLOVIĆ (1890–1949) AND THE IDEA OF P. KOSTA Institute of Musicology SASA Institute of Musicology SASA This collective monograph has been published owing to the financial support of the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia KOSTA P. MANOJLOVIĆ (1890–1949) AND THE IDEA OF SLAVIC AND BALKAN CULTURAL UNIFICATION edited by Vesna Peno, Ivana Vesić, Aleksandar Vasić Institute of Musicology SASA Belgrade, 2017 CONTENTS Preface 9 INTRODUCTION 13 Ivana Vesić and Vesna Peno Kosta P. Manojlović: A Portrait of the Artist and Intellectual in Turbulent Times 13 BALKAN AND SLAVIC PEOPLES IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE 20TH CENTURY: INTERCULTURAL CONTACTS 27 Olga Pashina From the History of Cultural Relations between the Slavic Peoples: Tours of the Russian Story Teller, I. T. Ryabinin, of Serbia and Bulgaria (1902) 27 Stefanka Georgieva The Idea of South Slavic Unity among Bulgarian Musicians and Intellectuals in the Interwar Period 37 Ivan Ristić Between Idealism and Political Reality: Kosta P. Manojlović, South Slavic Unity and Yugoslav-Bulgarian Relations in the 1920s 57 THE KINGDOM OF SERBS, CROATS AND SLOVENES/YUGOSLAVIA BETWEEN IDEOLOGY AND REALITY 65 Biljana Milanović The Contribution of Kosta P. Manojlović to the Foundation and Functioning of the Južnoslovenski pevački savez [South-Slav Choral Union] 65 Nada Bezić The Hrvatski pjevački savez [Croatian Choral Union] in its Breakthrough Decade of 1924–1934 and its Relation to the Južnoslovenski pevački savez [South-Slav Choral Union] 91 Srđan Atanasovski Kosta P. -

Matica Srpska Department of Social Sciences Synaxa Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture

MATICA SRPSKA DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SYNAXA MATICA SRPSKA INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR SOCIAL SCIENCES, ARTS AND CULTURE Established in 2017 1 Editor-in-Chief Časlav Ocić (2017‒ ) Editorial Board Nenad Makuljević (Belgrade) Dušan Rnjak (Belgrade) Katarina Tomašević (Belgrade) Editorial Secretary Jovana Trbojević Language Editors Biljana Radić Bojanić Tamara Verežan Jovana Marinković Olivera Krivošić Sofija Jelić Proof Reader Aleksandar Pavić Articles are available in full-text at the web site of Matica Srpska http://www.maticasrpska.org.rs/ Copyright © Matica Srpska, Novi Sad, 2017 SYNAXA СИН@КСА♦ΣΎΝΑΞΙΣ♦SYN@XIS Matica Srpska International Journal for Social Sciences, Arts and Culture 1 NOVI SAD 2017 Publication of this issue was supported by City Department for Culture of Novi Sad WHY SYNAXA? In an era of growing global interdependence and compression of history, any sort of self-isolation might not only result in provincialization, peripheraliza- tion, or self-marginalization, but may also imperil the very survival of nations and their authentic cultures. In the history of mankind, ethno-contact zones have usually represented porous borders permeable to both conflict and cooperation. Unproductive conflict has been, by default, destructive, while the fruitful in- tersection and intertwining of cultures has strengthened their capacities for creative (self)elevation. During all times, especially desperate and dehuma- nizing ones, cultural mutuality has opened the doors of ennoblement, i.e., offered the possibility of bringing meaning to the dialectic of the conflict between the universal material (usually self-destructive) horizontal and the specific spiritual (auto-transcending) vertical. It would be naïve and pretentious to expect any journal (including this one) to resolve these major issues. -

(Beograd) the National Idea in Serbian Music of the 20Th Century

Melita Milin (Beograd) The National Idea in Serbian Music of the 20th Century If there was but one important issue to be highlighted concerning Serbian music of the 20th century, it would certainly be the question of musical nationalism. As in all other countries belonging to the so-called European periphery, composers in Serbia faced the problem of asserting both their belonging to the European musical commu- nity and specific differences. The former had to be displayed by their musical craftmanship and creative individuality, while the lat- ter were conveyed through the introduction of native folk elements as tokens of a specific identity. Stevan Mokranjac (1856{1914) was the key-figure among Serbian composers before World War I. On his numerous tours abroad (Thessaloniki, Budapest, Sofia, Istanbul, Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig, Moscow), he received considerable appraisal for his choral works, which were primarily suites based on folk music (\rukoveti"). These outstanding works even surpassed early exam- ples of Serbian musical nationalism composed by Kornelije Stankovi´c which had been presented for the first time forty years earlier in Vi- enna.1 The most important part of Stevan Mokranjac's output are his \rukoveti" and church music, both composed for a cappella choir (Serbian church music is traditionally vocal a cappella music), but he also composed some works for voice and piano, for strings and incidental music.2 Mokranjac was only two years younger than Leoˇs 1Kornelije Stankovi´c (1831{1865) studied at the Vienna conservatory where his professor of counterpoint was the famous Simon Sechter. Stankovi´c gave con- certs with piano and choral pieces based on Serbian folk melodies (mostly simple harmonisations) and church music - two liturgies - based on traditional Serbian church chant (the liturgies were performed in 1855 and 1861 in the Musikverein Hall in Vienna). -

Serbia's Deals with China Reveal Flawed Business

S Filip transparency. little with and loans, with projects infrastructure – funding investors foreign with practices business its of typical are China in signed have leaders Serbia’s that The agreements build a bypass around Serbia’s capital. Serbia’s around abypass build tember 18. tember Sep on Beijing to visit astate during project, a207-million-euro bypass, the of construction the for agreements two SinisaMalisigned mayor, Belgrade mer projects. ture infrastruc for loans the on rates terest asin aswell factory, bus the into vestor in the to subsidies big uppaying end STRATEGY BUSINESS FLAWED REVEAL CHINA WITH DEALS SERBIA’S Serbian Finance Minister and the for the and Minister Serbian Finance could Serbia fear experts However, RUDIC struct an industrial park and and park anindustrial struct con based manufacturer, bus inaBelgrade- invest panies to Chinese com for deals signed Chinarecently and erbia +381 11 4030 306 114030 +381 - - - - - - - for its Future its for Seen asD-Day Referendum Macedonia’s Page 8 dealings with the Asian superpower. Asian the with dealings inSerbia’s common become had practice this that adding job, the do to company aChinese pay Chinato from money ing borrow Serbia ismerely that warns vic tance,” his office said. said. hisoffice tance,” impor strategic isof “Thispass. project by new the to Serbia thanks through go now would goods of transport nancing. fi the for deals the of signing the saw over XiJinping, and Vucic Aleksandar However, economist Milan Kovace economist However, regional most that Mali claimed Chinese Serbianand Presidents, The Issue No. No. Issue [email protected] Continued on on Continued 259 Friday, September 28 - Thursday, October 11,2018 October 28-Thursday, September Friday, page 2 - - - - - - promises of increased economic ties between the two countries. -

Serbian Music: Yugoslav Contexts

Serbian Music: Yugoslav Contexts SERBIAN MUSIC: YUGOSLAV CONTEXTS Edited by Melita Milin and Jim Samson Published by Institute of Musicology SASA Technical editor Goran Janjić Cover design Aleksandra Dolović Number of copies 300 Printed by Colorgrafx ISBN 978-86-80639-19-2 SERBIAN MUSIC: YUGOSLAV CONTEXTS EDITED BY MELITA MILIN JIM SAMSON INSTITUTE OF MUSICOLOGY OF THE SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS BELGRADE 2014 This book has been published thanks to the financial support of the Ministry of edu- cation, science and technological development of the Republic of Serbia. Cover illustration: Vera Božičković Popović, Abstract Landscape, 1966. Courtesy of Zepter Museum, Belgrade. CONTENTS PREFACE............................................................................................................7 Melita Milin INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................9 Jim Samson 1. SERBIAN MUSIC IN WESTERN HISTORIOGRAPHY......................17 Katy Romanou 2. WRITING NATIONAL HISTORIES IN A MULTINATIONAL STATE..........................................................................................................29 Melita Milin 3. DISCIPLINING THE NATION: MUSIC IN SERBIA UNTIL 1914 ................................................................................................47 Biljana Milanović 4. IMAGINING THE HOMELAND: THE SHIFTING BORDERS OF PETAR KONJOVIĆ’S YUGOSLAVISMS........................................73 Katarina Tomašević 5. THE INTER-WAR CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN MILOJE -

Education in Serbian Language in Kosovo

EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES KOSOVO EDUCATION IN SERBIAN LANGUAGE IN KOSOVO November, 2018 Co-financed by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Pristina Acknowledgement EUROPEAN CENTRE “Serbian Language Education in Kosovo” is a reportproduced by the European Center for Minority FOR MINORITY Issues Kosovo (ECMI Kosovo), as part of the project “Support to Education in Serbian language in ISSUES KOSOVO Kosovo: UMN Diploma Verification Process, Research on the Current Situation, Development of a MEST roadmap and Direct Training to UMN and Its Teaching Staff”. This projectis funded by the European Union and managed by the European Union Office in Kosovo; co-financing is provided by the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Kosovo. We would like to thank the Office for Community Affairs in the Office of the Prime Minister and various school administrations in charge of teaching in Serbian language schools in Kosovo, without whose support this research would have been impossible. ECMI Kosovo www.ecmikosovo.org EDUCATION IN SERBIAN ECMI Kosovo is the principal non-governmental organisation engaged with minority issues in Kosovo, with the overarching aim to develop inclusive, representative, community-sensitive institutions that support a stable multi-ethnic Kosovo. ECMI Kosovo contributes to the developing, LANGUAGE IN KOSOVO strengthening and implementation of relevant legislation, supports the institutionalisation of communities-related governmental bodies, and enhances the capacity of civil society actors and the government to engage with one another in a constructive and sustainable way. Str. Zahir Pajaziti Nr.20 Apt.5 10000 Prishtinë/Priština, Kosovo, Tel. +381 (0) 38 224 473 www.ecmikosovo.org Disclaimer This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union and the Royal Norwegian Embassy in Prishtinë/Priština. -

15-22 Maggio 2010

Diocesi di Vicenza - Ufficio Pellegrinaggi Itinerario religioso-culturale in 15-22 maggio 2010 PROGRAMMA Sabato 15 Maggio: ITALIA – BELGRADO Ritrovo dei partecipanti, sistemazione in pullman e partenza per l’aeroporto di Venezia. Operazioni d’imbarco sul volo per Vienna e proseguimento per Belgrado. All’arrivo trasferimento e sistemazione in albergo. Cena e pernottamento. Domenica 16 Maggio: BELGRADO Pensione completa. Intera giornata dedicata alla visita della città. La fortezza di Kalemegdan, che ha una storia molto lunga: era il castrum romano distrutto ed abbattuto molte volte da invasori successivi, fu ricostruito come un castello dai Bizantini nel XII secolo; sotto il despota serbo Stefan Lazarevic, figlio del famoso (tzar) re Lazar, Belgrado diventò la capitale del regno dei Serbi e la fortezza fu rinforzata. La cattedrale ortodossa serba “Saborna crkva”, edificata tra il 1837 ed il 1840 per ordine del principe Milos Obrenovic, progettata dall’architetto Adam Fridih Kverfeld. Nel pomeriggio visita della chiesa “Il Santo Sava”, iniziata nel 1935, i lavori furono interrotti allo scoppio della II guerra mondiale e vennero ripresi solo nel 1985. Lunedì 17 Maggio: BELGRADO – DONJI MILANOVAC Dopo la prima colazione visita al parco archeologico di Viminacium: città e campo militare della Roma imperiale dal I a V secolo dopo Cristo. Segue visita alla città medievale fortificata di Golubac, costruita su una roccia quasi inconquistabile sulle rive del Danubio. Successivamente visita al sito archeologico di Lepenski Vir. Proseguimento per Donji Milanovac, sistemazione in albergo, cena e pernottamento. Martedì 18 Maggio: DONJI MILANOVAC – PARAĆIN Partenza per Negotin, città natale del compositore Stevan Stojanović Mokranjac (1856-1914) che fu uno dei compositori ed educatori serbi più famosi.