Cfreptiles & Amphibians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures

Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation A report on Problems of Salination of Land in Coastal Areas of India and Suitable Protection Measures Hydrological Studies Organization Central Water Commission New Delhi July, 2017 'qffif ~ "1~~ cg'il'( ~ \jf"(>f 3mft1T Narendra Kumar \jf"(>f -«mur~' ;:rcft fctq;m 3tR 1'j1n WefOT q?II cl<l 3re2iM q;a:m ~0 315 ('G),~ '1cA ~ ~ tf~q, 1{ffit tf'(Chl '( 3TR. cfi. ~. ~ ~-110066 Chairman Government of India Central Water Commission & Ex-Officio Secretary to the Govt. of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Room No. 315 (S), Sewa Bhawan R. K. Puram, New Delhi-110066 FOREWORD Salinity is a significant challenge and poses risks to sustainable development of Coastal regions of India. If left unmanaged, salinity has serious implications for water quality, biodiversity, agricultural productivity, supply of water for critical human needs and industry and the longevity of infrastructure. The Coastal Salinity has become a persistent problem due to ingress of the sea water inland. This is the most significant environmental and economical challenge and needs immediate attention. The coastal areas are more susceptible as these are pockets of development in the country. Most of the trade happens in the coastal areas which lead to extensive migration in the coastal areas. This led to the depletion of the coastal fresh water resources. Digging more and more deeper wells has led to the ingress of sea water into the fresh water aquifers turning them saline. The rainfall patterns, water resources, geology/hydro-geology vary from region to region along the coastal belt. -

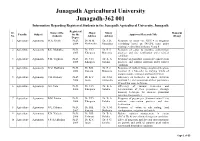

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001

Junagadh Agricultural University Junagadh-362 001 Information Regarding Registered Students in the Junagadh Agricultural University, Junagadh Registered Sr. Name of the Major Minor Remarks Faculty Subject for the Approved Research Title No. students Advisor Advisor (If any) Degree 1 Agriculture Agronomy M.A. Shekh Ph.D. Dr. M.M. Dr. J. D. Response of castor var. GCH 4 to irrigation 2004 Modhwadia Gundaliya scheduling based on IW/CPE ratio under varying levels of biofertilizers, N and P 2 Agriculture Agronomy R.K. Mathukia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. P. J. Response of castor to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Marsonia practices and zinc fertilization under rainfed condition 3 Agriculture Agronomy P.M. Vaghasia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of groundnut to moisture conservation 2005 Khanpara Golakia practices and sulphur nutrition under rainfed condition 4 Agriculture Agronomy N.M. Dadhania Ph.D. Dr. B.B. Dr. P. J. Response of multicut forage sorghum [Sorghum 2006 Kaneria Marsonia bicolour (L.) Moench] to varying levels of organic manure, nitrogen and bio-fertilizers 5 Agriculture Agronomy V.B. Ramani Ph.D. Dr. K.V. Dr. N.M. Efficiency of herbicides in wheat (Triticum 2006 Jadav Zalawadia aestivum L.) and assessment of their persistence through bio assay technique 6 Agriculture Agronomy G.S. Vala Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Efficiency of various herbicides and 2006 Khanpara Golakia determination of their persistence through bioassay technique for summer groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) 7 Agriculture Agronomy B.M. Patolia Ph.D. Dr. V.D. Dr. B. A. Response of pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan L.) to 2006 Khanpara Golakia moisture conservation practices and zinc fertilization 8 Agriculture Agronomy N.U. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Dr. Anand Shukla

Dr. Anand Shukla Associate Professor U N Mehta Institute of Cardiology and Research Centre, Ahmedabad of Cardiology Interventional HCG Multispeciality Hospital - Navarangpura, Ahmedabad Cardiologist Date of Birth 30th November 1971 Medical Education MBBS March 1989 -March 1994, Smt NHL Municipal Medical College, Ahmedabad, Gujarat University. One Year Internship: April 1994-March 1995 MD (Internal April 1995- 1998 - Seth Vadilal Sarabhai General Hospital & K M medicine) School of Postgraduate Medicine and Research, Ahmedabad Gujarat University Dissertation: "Serum ascites albumin gradient to diagnoseaetiology of Ascites." Senior resident July 1998 to Jun 1999 at NHL MMC, V.S. hospital Cardiology July 1999 to Dec 2000 S.G.P.G.I. Lucknow. D.M. Cardiology Jan 2001-Dec 2004. Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute, Lucknow Interventional Feb 2005-July 2005 - Krishna Heart Institute, Ahmedabad Cardiology Assistant Professor Aug 2005 – April 2005 - Department of Cardiology, Smt NHL Municipal Medical College & Seth Vadilal Sarabhai Hospital, Ahmedabad, India Assistant Professor May 2006- April 2010 - Department of Cardiology U N Mehta Institute of Cardiology and Research Centre, Ahmedabad, India Associate Professor Since Jun 2010 till date U N Mehta Institute of Cardiogy Licensure G-23155. M.B.B.S. India Gujarat Medical G-8280. M.D.Medicine and Therapeutics Council G-19427. D.M.(cardiology) Research Activities Awards Won Dr. SarleAward for presentation of best paper in scientific session in 56th annual National conference of the Cardiological Society of India , Banglore 2004. "A prospective study on prevention of Atherosclerosis Progression in Normolipidemic Patients Using Statin." Won a best paper award at state level conference 2000. "Clinical Utility of Dobutamine Stress Echo Cardiography, Vadodara, Gujarat." Co-Author Won CSI Travel award for best paper entitled "Determinants of Left atrial pressures in Mitral Stenosis: role of LA Stiffness" at the 54th National Cardiological Society of India Conference, Kochi 2002. -

Indiana University Common Property Land Resources

INDIANA UNIVERSITY COMMON PROPERTY LAND RESOURCES Past,Present and Perspectives (with special reference to Gujarat-India) S.A.SHAH Indian Forest Service(Retired) International Tree Crops Institute,India Paper contributed to Common Property Conference,Winnipeg 26-29 September,1991 COMMON PROPERTY LAND RESOURCES Past,Present & Perspectives (With special reference to Gujarat-India) Introduction India is a populous (844 million)and energy poor (import of energy consumes the highest foreign exchange,)country with a high foreign debt and adverse trade balance,agriculture based economy(GDP from agri.about 50%)and adverse Land/Man ratio.Poverty is therefore,an expected consequence.Under such an environment/Common Property Land Resources(CPLR)are vitally important particularly for the rural poor who have to depend on them for meeting their every day forest based subsistence needs which they can obtain just for the cost of harvesting!Since India is about 80% rural and about 5056 of the population is poor,CPLR acquire a special significance from a national perspective.If right priorities for alleviating poverty are to be followed,development of CPLR should come first.Unfortunately,it did not receive any attention until very recently.Perhaps Politicians,PlannersAdministrators Sociologists and Economists are not aware of the role and potential of CPLR in social,economic and cultural welfare of the rural communitiesIThis conference is,therefore not a day too soon and I hope,would create the necessary awareness leading to concerted action. Country Scene India is situated between 8 degrees 4'and 37 degrees 6' North latitude and 68 degrees 7' and 97 degrees 25' East longitude.lt covers an area of 328,7780Sq.Km..The highest mountain range the Himalayas forms the northern boundary with the highest peak having an altitude of about 7190 meters.Naturally therefore,the rainfall and temperatures are extremely variable;all the diverse climates of the world are represented. -

Gujarat State

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENEATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUNDWATER YEAR BOOK – 2018 - 19 GUJARAT STATE REGIONAL OFFICE DATA CENTRE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD May - 2020 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENEATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUNDWATER YEAR BOOK – 2018 -19 GUJARAT STATE Compiled by Dr.K.M.Nayak Astt Hydrogeologist REGIONAL OFFICE DATA CENTRE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD May - 2020 i FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board, West Central Region, has been issuing Ground Water Year Book annually for Gujarat state by compiling the hydrogeological, hydrochemical and groundwater level data collected from the Groundwater Monitoring Wells established by the Board in Gujarat State. Monitoring of groundwater level and chemical quality furnish valuable information on the ground water regime characteristics of the different hydrogeological units moreover, analysis of these valuable data collected from existing observation wells during May, August, November and January in each ground water year (June to May) indicate the pattern of ground water movement, changes in recharge-discharge relationship, behavior of water level and qualitative & quantitative changes of ground water regime in time and space. It also helps in identifying and delineating areas prone to decline of water table and piezometric surface due to large scale withdrawal of ground water for industrial, agricultural and urban water supply requirement. Further water logging prone areas can also be identified with historical water level data analysis. This year book contains the data and analysis of ground water regime monitoring for the year 2018-19. -

Annexure-26 the Details About Number of Students Selected During Campus Interviews by Different Employers

NAAC – Reaccreditation Report Annexure-26 The details about number of Students Selected during Campus Interviews by different Employers Sr. Name of the Employer/Company Number of No. students selected 2014-15 1 INTAS Pharmaceuticals, Ahmedabad 2 2 Alembic Pharmaceutics Ltd., Vadodara 2 3 Amoli Organics Pvt. Ltd., Vadodara 6 4 Lupin Limited, Vadodara 4 5 Unimark Remedies LTd., Ahmedabad 6 6 Intas Pharmaceuticals Ltd., Ahmadabad 8 7 Adroit Pharmachem Pvt. Ltd., Majusar 3 8 Apothecone Pharmaceutical Pvt. Ltd,, Vadodara 4 9 Tata Consultancy Pvt. Ltd., Gandhinagar 6 10 Vrindi India Pvt. Ltd., Anand 5 11 Proseon Technologies Pvt Ltd, Vadodara 2 12 Mobile Internet Pvt. Ltd., Ahmedabad 1 13 Flexiware Solutions, Ahmedabad 2 14 BISAG(Bhaskaracharya Institute For Space Applications 6 and Geo-Informatics), Gandhinagar 15 GCMMF(Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation 4 Ltd (GCMMF) , Anand 16 EITL(Elecon Information Technology Limited), V V 1 Nagar 17 SPEC INDIA, Ahmedabad 3 18 ATOS, Vadodara 2 19 ACCUTRON INC, India Branch, Ahmedabad 5 20 Diamond crucible, Mehsana 01 21 Alembic , Vadodara 1 22 Sciformix Technologies Private Limited, Pune 2 23 Punyam management service pvt ltd, Ahmedabad 1 24 Manoria Associate, Ahmedabad 3 25 RSM Astute, Surat 2 26 Vidya Wires Pvt Ltd, Vallabh Vidyanagar 2 27 Ravi Energy, Baroda 2 28 JS Corrupack Pvt. Ltd., Savli 1 29 Fusion Management Group, Ahmedabad 1 30 Jay Chemical Industries Limited, Ahmedabad 1 31 Manoria Associate, Ahmedabad 1 537 Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Gujarat NAAC – Reaccreditation Report 32 Manoria Associate, Ahmedabad 1 33 C. M. Smith & Sons Limited, Nadiad 1 34 Jidaan Technology, Ahmedabad 1 35 Sujay Engineering, Vadodara 1 36 Manoria Associate, Ahmedabad 1 37 Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producer Union Ltd., 1 Anand 38 SE Electricals LTD, Vadodara 1 39 Sharda Industries Ltd., 1 40 SE Electricals LTD, Vadodara 1 41 Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producer Union Ltd., 1 Anand 42 Unique Forgings Pvt. -

India's Milk Revolution

A case study from Reducing Poverty, Sustaining Growth—What Works, What Doesn’t, and Why A Global Exchange for Scaling Up Success Public Disclosure Authorized Scaling Up Poverty Reduction: A Global Learning Process and Conference Shanghai, May 25–27, 2004 India’s Milk Revolution— Investing in Rural Producer Public Disclosure Authorized Organizations Dr. Verghese Kurien, Chairman, Institute of Rural Management, Anand – 388001 Gujarat, India Tel: +91-2692-261655/262422/261230 Development partner: World Bank/EEC Food Aid Public Disclosure Authorized The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank cannot guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. Copyright © 2004. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK All rights reserved. The material in this work is copyrighted. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or inclusion in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the World Bank. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its work and will normally grant permission promptly. Public Disclosure Authorized INDIA’S MILK REVOLUTION—INVESTING IN RURAL PRODUCER ORGANIZATIONS Executive Summary Over the last 25 years or so, the Indian dairy industry has progressed from a situation of scarcity to that of plenty. Dairy farmers today are better informed about technologies of more efficient milk production and their economics. Even the landless and marginal farmers now own highly productive cows and buffaloes in many areas. -

Physico Chemical Characterization of Ground Water of Anand District, Gujarat, India

I Research Journal of Environment Sciences__________________________________ I Res. J. Environment Sci. Vol. 1(1), 28-33, August (2012) Physico chemical Characterization of ground water of Anand district, Gujarat, India Bhattacharya T. 1, Chakraborty S. 1 and Tuck Neha 2 1Dept. Environmental Science and Engineering, Birla Institute of Technology, Mesra, Ranchi, Jharkhand, INDIA 2 Dept. Environmental Science and Technology, ISTAR, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Anand, Gujarat-388120, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in Received 23 rd July 2012, revised 28 th July 2012, accepted 30 th July 2012 Abstract A report of physico-chemical study of the water samples taken from the Anand district of central Gujarat is presented here. Water samples from 42 sites have been subjected to physico- chemical analysis including parameters viz. pH, TDS, conductivity, hardness, dissolved oxygen, chloride, nitrate, phosphate, fluoride, iron and boron. Observations indicated pH, nitrate and phosphate values to be within permissible limit, TDS showed variable results while conductivity was high total hardness was slightly higher in some sampling locations, otherwise within the limits. Fe and boron was significantly high in all the locations. Fluoride was also absent in all the locations except Borsad. Chloride was considerably high only in Khambhat. The results were used to calculate the water quality index to draw conclusion about the suitability of the water for drinking and other domestic applications. Keywords: Ground water, physico-chemical analysis, water quality index. Introduction north east to the south west 11 . Along with these facts, as per the demographic trends, the population in the district is anticipated to Groundwater is the most important source of drinking water in India. -

Groundwater and Well-Water Quality in Alluvial Aquifer of Central Gujarat

Groundwater and well-water quality in Alluvial aquifer of Central Gujarat Sunderrajan Krishnan1, Sanjiv Kumar2, Doeke Kampman3 and Suresh Nagar4 1 International Water Management Institute(IWMI), Elecon campus, Anand, Gujarat - 388120 2 Xavier Institute of Development and Studies, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh (Intern in IWMI) 3 Trent University, Netherlands (Intern in IWMI) 4 Central Groundwater Board, Ahmedabad Division ABSTRACT Contamination of aquifers is an increasing problem in several parts of India. This, along with scarcity of groundwater resources due to increase in water demand and also by reduction in recharge of groundwater from changing landuse, combine to further compound the problem. In Gujarat state of Western India, a variety of groundwater pollution problems have emerged in the past two decades. High Salinity, Fluoride, Nitrate and pollution from industrial effluents have caused contamination of aquifers in different parts of the state. The Mahi right Bank command (MRBC) aquifer is the Southern tip of the Alluvial North Gujarat aquifer. The drinking water requirement of Anand and Kheda districts that overlay this aquifer is dependant mainly on groundwater. The rural areas are mostly dependant on the Village Panchayat managed water supply system and a combination of private and government handpumps apart from regional piped water supply in some areas. The general lack of awareness of water quality allows the spread of water-borne diseases, especially during the monsoon season. A combination of organizations –IWMI, FES and some medical organizations - came together to assess the extant of biological contamination of well-water after heavy floods in July 2006 and create awareness among the users to follow proper treatment procedures. -

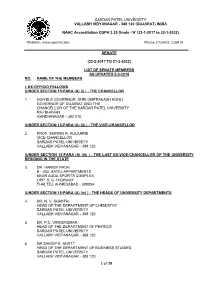

SENATE FINAL LIST AS on 5-3-2018 New.Pdf

SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120 (GUJARAT) INDIA NAAC Accreditation CGPA 3.25 Grade -'A' (23-1-2017 to 22-1-2022) Website : www.spuvvn.edu Phone: (02692) 226819 SENATE (22-2-2017 TO 21-2-2022) LIST OF SENATE MEMBERS AS UPDATED 5-3-2018 NO. NAME OF THE MEMBERS I. EX-OFFICIO FELLOWS (UNDER SECTION 15-PARA (A) (i) ) - THE CHANCELLOR 1. HON’BLE GOVERNOR. SHRI OMPRAKASH KOHLI GOVERNOR OF GUJARAT AND THE CHANCELLOR OF THE SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY RAJ BHAVAN GANDHINAGAR - 382 010. (UNDER SECTION 15-PARA (A) (ii) ) - THE VICE-CHANCELLOR 2. PROF. SHIRISH R. KULKARNI VICE-CHANCELLOR SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. (UNDER SECTION 15-PARA (A) (iii) ) - THE LAST EX-VICE-CHANCELLOR OF THE UNIVERSITY RESIDING IN THE STATE 3. DR. HARISH PADH B - 303, SATEJ APPARTMENTS NEAR AUDA SPORTS COMPLEX OPP. S. G. HIGHWAY THALTEJ, AHMEDABAD - 380054 (UNDER SECTION 15-PARA (A) (iv) ) - THE HEADS OF UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS 4. DR. N. V. SHASTRI HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF CHEMISTRY SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. 5. DR. P.C. VINODKUMAR HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. 6. DR.SANDIP K. BHATT HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS STUDIES, SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. 1 of 29 7. DR. DAYASHANKAR TRIPATHI HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HINDI SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. 8. DR. R. K. MANDALIYA HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. 9. DR. NIRANJANKUMAR PUNAMCHAND PATEL HEAD OF THE DEPARTMENT OF SANSKRIT SARDAR PATEL UNIVERSITY VALLABH VIDYANAGAR - 388 120. -

C V M's SEMCOM Vallabh Vidyanagar

C V M’s SEMCOM Vallabh Vidyanagar ENVIRONMENTAL AUDIT (2015-16) The internal review of environmental management system for 2015-16 has been conducted by Environmental Cell. Sr. Element Findings No 1 Environmental policy The Environmental Management System has been framed for the institution. The policy aims at keeping the college campus clean, preserve the required greenery, create awareness among the students about environmental issues, reduce wastage of energy and have good housekeeping in the campus. The policy has been notified vide circular dated 23 August 2015. 2 Energy Energy is a crucial resource. Economy in consumption of electricity is consciously followed. The electricity units consumed in 2014-15 (81,959) while that for the year 2015- 16 is (78858) which is reduction of consumption by 4%. Suitable notice/stickers are kept in all the class rooms so that the students do not waste the power. Solar water system has been installed at Bhaikaka Hostel & Square Hostel. The environmental policy has been communicated to the students and other stakeholders. 3 Environment The relevant environmental issues are addressed by the college in its activities. In all such activities the students are involved, so that they develop required concern about environmental issues. The students prepare various posters about environment conservation. Tree plantation was organized on 7th August 2015 at village Kasor, Dharmaj (Dist. : Anand) where more than 500 trees were planted. In this programme, 45 students of different classes participated. The students’ council organizes tree plantation during monsoon since 2003. Green business fair is organized since 2010-11. During the year, Green Business & Technology Fair was organized on 12 & 13th February, 2016 to spread the 1 message of green products and environment to the students and local society.