Conceptual Hurdles to the Application of Atkins V. Virgina Lois A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cognitive Psychology, 6Th Edition by Robert J. Sternberg and Karin Sternberg (Z-Lib.Org)

1 CHAPTER Introduction to Cognitive Psychology CHAPTER OUTLINE Cognitive Psychology Defined Three Cognitive Models of Intelligence Philosophical Antecedents of Psychology: Carroll: Three-Stratum Model of Intelligence Gardner: Theory of Multiple Intelligences Rationalism versus Empiricism Sternberg: The Triarchic Theory Psychological Antecedents of Intelligence of Cognitive Psychology Research Methods in Cognitive Psychology Early Dialectics in the Psychology of Cognition Goals of Research Understanding the Structure of the Mind: Distinctive Research Methods Structuralism Experiments on Human Behavior Understanding the Processes of the Mind: Psychobiological Research Functionalism Self-Reports, Case Studies, An Integrative Synthesis: Associationism and Naturalistic Observation It’s Only What You Can See That Counts: Computer Simulations and Artificial Intelligence From Associationism to Behaviorism Putting It All Together Proponents of Behaviorism Fundamental Ideas in Cognitive Psychology Criticisms of Behaviorism Behaviorists Daring to Peek into the Black Box Key Themes in Cognitive Psychology The Whole Is More Than the Sum of Its Parts: Summary Gestalt Psychology Thinking about Thinking: Analytical, Creative, Emergence of Cognitive Psychology and Practical Questions Early Role of Psychobiology Add a Dash of Technology: Engineering, Key Terms Computation, and Applied Cognitive Psychology Media Resources Cognition and Intelligence What Is Intelligence? 1 2 CHAPTER 1 • Introduction to Cognitive Psychology Here are some of the questions we will explore in this chapter: 1. What is cognitive psychology? 2. How did psychology develop as a science? 3. How did cognitive psychology develop from psychology? 4. How have other disciplines contributed to the development of theory and research in cognitive psychology? 5. What methods do cognitive psychologists use to study how people think? 6. -

An Academic Genealogy of Psychometric Society Presidents

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) An Academic Genealogy of Psychometric Society Presidents Wijsen, L.D.; Borsboom, D.; Cabaço, T.; Heiser, W.J. DOI 10.1007/s11336-018-09651-4 Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Published in Psychometrika License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wijsen, L. D., Borsboom, D., Cabaço, T., & Heiser, W. J. (2019). An Academic Genealogy of Psychometric Society Presidents. Psychometrika, 84(2), 562-588. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-018-09651-4 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 psychometrika—vol. 84, no. 2, 562–588 June 2019 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-018-09651-4 AN ACADEMIC GENEALOGY OF PSYCHOMETRIC SOCIETY PRESIDENTS Lisa D. -

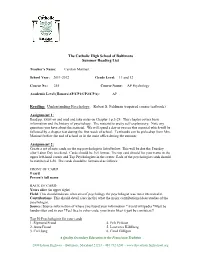

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Reading

The Catholic High School of Baltimore Summer Reading List Teacher’s Name: Carolyn Marinari School Year: 2011-2012______________ Grade Level: 11 and 12 Course No.: 255 Course Name: AP Psychology Academic Level (Honors/AP/CP1/CP2/CPA): AP Reading: Understanding Psychology, Robert S. Feldman (required course textbook) Assignment 1: Read pp. xxxiv-iii and read and take notes on Chapter 1 p.3-29. This chapter covers basic information and the history of psychology. The material is pretty self-explanatory. Note any questions you have about the material. We will spend a day or two on this material which will be followed by a chapter test during the first week of school. Textbooks can be picked up from Mrs. Marinari before the end of school or in the main office during the summer. Assignment 2: Create a set of note cards on the top psychologists listed below. This will be due the Tuesday after Labor Day weekend. Cards should be 3x5 format. The top card should list your name in the upper left-hand corner and Top Psychologists in the center. Each of the psychologist cards should be numbered 1-50. The cards should be formatted as follows: FRONT OF CARD # card Person's full name BACK OF CARD Years alive (in upper right) Field: This should indicate what area of psychology the psychologist was most interested in. Contributions: This should detail (succinctly) what the major contributions/ideas/studies of the psychologist. Source: Source information of where you found your information *Avoid wikipedia *Must be handwritten and in pen *Feel free to color-code, your brain likes it-just be consistent!! Top 50 Psychologists for your cards 1. -

Summer Assignment 2021

Welcome to AP Psychology! 2021 SUMMER ASSIGNMENT Ms. Nordone I am excited that you have decided to schedule this class and challenge yourself with the fascinating world of psychology. I am certain that you will find this course worthwhile and personally relevant. Although it is the summer, there is work to be done. Please note, AP Psychology is an elective, college-level course with higher student expectations than most courses taken by high school students. With that being said, it is imperative that we get a jump start on the AP Psychology curriculum. It is mandatory and, in your best interest, to complete the summer assignment. Your summer assignment consists of FOUR mini-assignments. Each assignment will serve a specific purpose that will assist you throughout the school year and aid in your preparations for the AP Exam in May, 2022. Summer Assignment #1 – “ Who’s Who?” Create Your Cards! Names to Know for the AP Psychology Exam Directions: You will create either a set of cards for the 38 most influential Psychologists. Using a reputable web source (www.famouspsychologists.org) or another search engine of your choice, look up each of the names below and research each of these psychologists. Use the template provided in Google Classroom or another program that designs flash cards. Read about their studies, their theories, and influential research relative to the field of psychology. On your flash card you should provide the person’s name and a detailed description of these things. (i.e. what they are most famous for in the field of -

The Making of California's Framework, Standards, and Tests for History

“WHAT EVERY STUDENT SHOULD KNOW AND BE ABLE TO DO”: THE MAKING OF CALIFORNIA’S FRAMEWORK, STANDARDS, AND TESTS FOR HISTORY-SOCIAL SCIENCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Bradley Fogo July 2010 © 2010 by Bradley James Fogo. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/mg814cd9837 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Samuel Wineburg, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Labaree I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Milbrey McLaughlin Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements: I wish to thank my adviser Sam Wineburg for the invaluable guidance and support he provided on this project from its inception to the final drafting. -

1 VITA NAME: Robert J. Sternberg ADDRESS: Department of Human Development, Cornell University, 116 Reservoir Ave., B44

VITA OF ROBERT J. STERNBERG 1 VITA NAME: Robert J. Sternberg ADDRESS: Department of Human Development, Cornell University, 116 Reservoir Ave., B44 MVR Hall, Ithaca, N 14853-4401 PHONE: 607-882-0001 E-MAIL: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Stanford University, 1975 (Psychology); Advisor, Gordon Bower B.A., Yale University, 1972 (Psychology); Advisor, Endel Tulving Impact Indices (Google Scholar): Number of citations = 141,084 h index = 184 (number h of works cited at least h times) i10 Index = 900 (number of works cited at least 10 times) HONORS AND AWARDS Honorary Doctorates: Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Huelva, Spain, 2012 Doctor of Humanities, Honoris Causa, De la Salle University, Manila, Philippines, 2011 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Connecticut, Storrs, Connecticut, USA, 2009 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, Eureka College, Illinois, USA, 2008 Doctor Honoris Causa, Ricardo Palma University, Peru, 2008 Doctor Honoris Causa, Tilburg University, Holland, 2007 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, St. Petersburg State University, Russia, 2006 Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Durham, England, 2006 Doctor Honoris Causa, Constantine the Philosopher University, Nitra, Slovakia, 2004 Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Leuven, Belgium, 2001 Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Cyprus, Cyprus, 2000 Doctor Honoris Causa, University of Paris V, France, 2000 Doctor Honoris Causa, Complutense University, Madrid, Spain, 1994 Scholarly Prizes and Awards: 1/20/2018 VITA OF ROBERT J. STERNBERG 2 Grawemeyer -

PCS AP Psych 0280

A Planned Course of Study for Advanced Placement Psychology ASHS Course # 0280 Abington School District Abington, Pennsylvania September, 2016 a. Objectives Students will demonstrate the appropriate level of proficiency in each of the following areas: History and Approaches • Recognize how philosophical and physiological perspectives shaped the development of psychological thought . • Describe and compare different theoretical approaches in explaining behavior: — structuralism, functionalism, and behaviorism in the early years; — Gestalt, psychoanalytic/psychodynamic, and humanism emerging later; — evolutionary, biological, cognitive, and biopsychosocial as more contemporary approaches . • Recognize the strengths and limitations of applying theories to explain behavior . • Distinguish the different domains of psychology (e .g ., biological, clinical, cognitive, counseling, developmental, educational, experimental, human factors, industrial–organizational, personality, psychometric, social) . • Identify major historical figures in psychology (e .g ., Mary Whiton Calkins, Charles Darwin, Dorothea Dix, Sigmund Freud, G . Stanley Hall, William James, Ivan Pavlov, Jean Piaget, Carl Rogers, B . F . Skinner, Margaret Floy Washburn, John B . Watson, Wilhelm Wundt) Research Methods • Differentiate types of research (e .g ., experiments, correlational studies, survey research, naturalistic observations, case studies) with regard to purpose, strengths, and weaknesses . • Describe how research design drives the reasonable conclusions that can be -

HD Scholarship in 2015

Department of Human Development/ HD Scholarship in 2015 HD Scholarship January 2015 Publications Sternberg, R.J., & Bridges, S.L. (2014). Varieties of genius. In D. K. Simonton (Ed.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of genius (pp. 185-197). New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell. Grant Awards Christopher Vredenburgh was recently awarded a two year National Research Service Award (NRSA) Individual Predoctoral Fellowship by the NIH to finish his dissertation work. He was also named one of 6 Department of Health and Human Services Head Start Graduate Student Research Scholars - 2 year grant funding his doctoral dissertation research. HD Scholarship February 2015 Publications Alea, N., & Wang, Q. (2015) (Eds.). Going global: The functions of autobiographical memory in cultural context. Special Issue in Memory, Volume 23, Issue 1. Hess, T., Strough, J. & Löckenhoff, C.E. (Eds.) (2015) Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. Elsevier. Löckenhoff, C.E., Lee, D.S., Buckner, M.L., Moreira, M.O., Martinez, S.J. & Sun, M.Q. (2015). Cross-cultural differences in attitudes about aging: Moving beyond the East-West dichotomy. In S.T.Cheng, I. Chi, H. Fung, L. Li, & J. Woo (Eds.). Successful aging: Asian perspectives. Springer. Löckenhoff, C.E., & Rutt, J.L. (2015). Age differences in time perceptions and their implications for decision making across the lifespan. In T. Hess, J. Strough, & C.E. Löckenhoff (Eds.). Aging and decision making: Empirical and applied perspectives. Elsevier. Mendle, J., Moore, S.R., Briley, D. & Harden K.P. (2015). Puberty, socioeconomic status in girls: evidence for gene x environment interactions. Clinical Psychological Science. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1177/2167702614563598 Reyna, V.F., Brainerd, C.J. -

ED 315 663 CE 054 810 AUTHOR Fellenz, Robert A.; Conti, Gary J. TITLE Learning and Reality

DOCUMENT RESUM7, ED 315 663 CE 054 810 AUTHOR Fellenz, Robert A.; Conti, Gary J. TITLE Learning and Reality: Reflections on Trends in Adult Learning. information Series No. 336. INSTITUTION ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education, Columbus, Ohio. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Re5:earch and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 89 CONTRACT PI88062005 NOTF 44p. AVAILABLE FROMPublications Office, Center on Education and Training for Employment, 1900 Kenny Road, Columbus, OH 43210-1090 (order no. IN336: $5.25). PUB TYPE Information Analyses - ERIC Information Analysis Products (071) EDRS PRICE MF01/Prn2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Adult Learning; *Adult Students; Cognitive Processes; *Cognitive Psychology; Cognitive Style; Critical Thinking; Cultural Context; Educational Research; Educational Trends; *Learning Strategies; Memory; Metacognition; Participatory Research; Social Action; *Social Environment ABSTRACT The focus of thc, adult education field is shifting to adult learning. Current trends are the continued development of the concept: of andragogy and self-directed learning, increased emphasis on learning how to learn, and real-life learning. Cognitive psycholo,j is influencing work in adult learning. The concept of intelligence as it relates to adults is moving avay from the notion of IQ toward a recogn-it4.on that intelligence has multiple aspects. Application of the concept of learning style has been Hindered by confusion over terminology and lack of appropriate measurement instruments fc.1 adults. The teaching of learning strategies to adults tends to emphasize metacognition, memory, and ixtivation. Critical thinking is becoming more important in an environment complicated by an in_ormation explosion and rapid social and technological change. The influence of the social environment and culture upon learning is also being examined. -

North American Journal of Psychology, 2001. ISSN ISSN-1527-7143 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 549P.; Published Semi-Annually

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 169 CG 031 104 AUTHOR McCutcheon, Lynn E., Ed. TITLE North American Journal of Psychology, 2001. ISSN ISSN-1527-7143 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 549p.; Published semi-annually. AVAILABLE FROM NAJP, 240 Harbor Dr., Winter Garden, FL 34787 ($30 per annual subscription). Tel: 407-877-8364; Web site: http://najp.8m.com. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT North American Journal of Psychology; v3 n1-3 2001 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF02/PC22 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Psychology; *Research Tools; *Scholarly Journals; *Social Science Research ABSTRACT "North American Journal of Psychology" publishes scientific papers of general interest to psychologists and other social scientists. Articles included in volume 3 issue 1(March/April 2001) are: "Sense of Humor in Black and White"; "Convergent Validity of the Situational Outlook Questionnaire"; "Alcohol Consumption and Consequences in a Sample of University Undergraduates"; "Psychology and Religion: Indicators of Integration"; "Descriptions of Religious Experience among U.S. Christians and Malaysian Muslims"; "The Best Laid Plans of Mice and Men: The Role of Decision Confidence in Outcome Success"; "Disposition toward Thinking Critically: A Comparison of Preservice Teachers and Other University Students"; "An Interview with Robert Sternberg about Learning Disabilities"; "Interdisciplinarity and the Cross-Training of Clinical Psychologists: Preparing Graduates for Hybrid Careers"; "Validity Comparison of the General Ability Measure for Adults with the Wonderlic Personnel Test." Articles included in volume 3 issue 2 (June/July 2001) are: "Parental Disciplinary History and Current Level of Empathy and Moral Reasoning among Late Adolescents"; "An Interview with Russell Eisenman"; "Differential Processes of Emotion Space over Time";. -

Resources for SEERC Phd Students in Research Track 2

Resources for SEERC PhD Students in Research Track 2 Information & Communication Technologies Contents General Advice ............................................................................................................... 2 Finding and Dealing with a Supervisor .......................................................................... 3 Finding a Topic ............................................................................................................... 3 Research Proposals ........................................................................................................ 3 Literature Search / Review ............................................................................................. 4 Writing Up ...................................................................................................................... 5 Citing and Referencing ................................................................................................... 9 Completion Problems .................................................................................................. 10 Writing, Publishing and Reviewing Research Papers ................................................... 12 Oral Presentations - Conferences, Posters, Talks ........................................................ 16 Research Ethics ............................................................................................................ 17 Career Advice for Graduates ....................................................................................... -

High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion, and Graduation Jay P

http://www.nap.edu/catalog/6336.html We ship printed books within 1 business day; personal PDFs are available immediately. High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion, and Graduation Jay P. Heubert and Robert M. Hauser, Editors; Committee on Appropriate Test Use, National Research Council ISBN: 0-309-52495-4, 352 pages, 6 x 9, (1999) This PDF is available from the National Academies Press at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/6336.html Visit the National Academies Press online, the authoritative source for all books from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, the Institute of Medicine, and the National Research Council: • Download hundreds of free books in PDF • Read thousands of books online for free • Explore our innovative research tools – try the “Research Dashboard” now! • Sign up to be notified when new books are published • Purchase printed books and selected PDF files Thank you for downloading this PDF. If you have comments, questions or just want more information about the books published by the National Academies Press, you may contact our customer service department toll- free at 888-624-8373, visit us online, or send an email to [email protected]. This book plus thousands more are available at http://www.nap.edu. Copyright © National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF File are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Distribution, posting, or copying is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. Request reprint permission for this book. High Stakes: Testing for Tracking, Promotion, and Graduation http://www.nap.edu/catalog/6336.html High Stakes TESTING FOR TRACKING, PROMOTION, AND GRADUATION Jay P.