Building the Femorabilia Special Collection Methodologies and Practicalities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Igncc18 Programme

www.internationalgraphicnovelandcomicsconference.com [email protected] #IGNCC18 @TheIGNCC RETRO! TIME, MEMORY, NOSTALGIA THE NINTH INTERNATIONAL GRAPHIC NOVEL AND COMICS CONFERENCE WEDNESDAY 27TH – FRIDAY 29TH JUNE 2018 BOURNEMOUTH UNIVERSITY, UK Retro – a looking to the past – is everywhere in contemporary culture. Cultural critics like Jameson argue that retro and nostalgia are symptoms of postmodernism – that we can pick and choose various items and cultural phenomena from different eras and place them together in a pastiche that means little and decontextualizes their historicity. However, as Bergson argues in Memory and Matter, the senses evoke memories, and popular culture artefacts like comics can bring the past to life in many ways. The smell and feel of old paper can trigger memories just as easily as revisiting an old haunt or hearing a piece of music from one’s youth. As fans and academics we often look to the past to tell us about the present. We may argue about the supposed ‘golden age’ of comics. Our collecting habits may even define our lifestyles and who we are. But nostalgia has its dark side and some regard this continuous looking to the past as a negative emotion in which we aim to restore a lost adolescence. In Mediated Nostalgia, Ryan Lizardi argues that the contemporary media fosters narcissistic nostalgia ‘to develop individualized pasts that are defined by idealized versions of beloved lost media texts’ (2). This argument suggests that fans are media dupes lost in a reverie of nostalgic melancholia; but is belied by the diverse responses of fandom to media texts. Moreover, ‘retro’ can be taken to imply an ironic appropriation. -

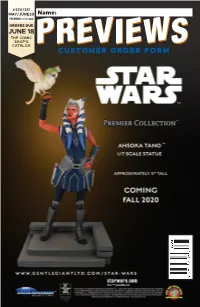

Customer Order Form

#380/381 MAY/JUNE20 Name: PREVIEWS world.com ORDERS DUE JUNE 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Cover COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 1:41:01 PM FirstSecondAd.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:49:06 PM PREMIER COMICS BIG GIRLS #1 IMAGE COMICS LOST SOLDIERS #1 IMAGE COMICS RICK AND MORTY CHARACTER GUIDE HC DARK HORSE COMICS DADDY DAUGHTER DAY HC DARK HORSE COMICS BATMAN: THREE JOKERS #1 DC COMICS SWAMP THING: TWIN BRANCHES TP DC COMICS TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES: THE LAST RONIN #1 IDW PUBLISHING LOCKE & KEY: …IN PALE BATTALIONS GO… #1 IDW PUBLISHING FANTASTIC FOUR: ANTITHESIS #1 MARVEL COMICS MARS ATTACKS RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT SEVEN SECRETS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS MayJune20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 5/7/2020 3:41:00 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Cimmerian: The People of the Black Circle #1 l ABLAZE 1 Sunlight GN l CLOVER PRESS, LLC The Cloven Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS The Big Tease: The Art of Bruce Timm SC l FLESK PUBLICATIONS Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Totally Turtles Little Golden Book l GOLDEN BOOKS 1 Heavy Metal #300 l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist l HERMES PRESS Titan SC l ONI PRESS Doctor Who: Mistress of Chaos TP l PANINI UK LTD Kerry and the Knight of the Forest GN/HC l RANDOM HOUSE GRAPHIC Masterpieces of Fantasy Art HC l TASCHEN AMERICA Jack Kirby: The Epic Life of the King of Comics Hc Gn l TEN SPEED PRESS Horizon: Zero Dawn #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2019 #9 l TITAN COMICS Negalyod: The God Network HC l TITAN COMICS Star Wars: The Mandalorian: -

|||GET||| the Eagle 2Nd Edition

THE EAGLE 2ND EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Rosemary Sutcliff | 9780312564346 | | | | | Make your Own PCBs with EAGLE (Second Edition) Clarke then an aspiring young science fiction writer. You must contact your FFL dealer before ordering to ensure they are open for business and able to perform the transfer. They are simply the best reference books on the market. Allow cookies. Posted February 17, Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Title pop Featured articles. Can't wait to get my grubby mits on mine This product is currently Out of Stock, No Backorder Here are some similar products currently available. Let us help! In The Eagle 2nd edition however, Hulton Press contacted Morris with the instruction "definitely interested do not approach any other publisher". Retrieved 27 May Werner, Jr. Hampson was enthusiastic about the idea, and in May that year the two began work on a dummy of it. I didn't want to produce a strip without a female. Watson stopped drawing Dan Dare inand was succeeded by Bruce Cornwell. Posted February 20, edited. Simultaneously disillusioned with contemporary children's literature, he and Anvil artist Frank Hampson created a dummy comic based on Christian values. In he became vicar of St. Morris went on to become editorial director of the National Magazine Companyand later its managing director and editor-in- chief. Can I ask the author for an The Eagle 2nd edition By jmelFebruary 17, in Reid Air Publications. I wanted to give hope for the future, to show that rockets, and science in general, could reveal new worlds, new opportunities. -

Books for You: a Booklist for Senior High Students

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 264 581 CS 209 485 AUTHOR Small, Robert C., Jr., Ed. TITLE Books for You: A Booklist for Senior High Students. New Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0359-6 PUB DATE 82 NOTE 331p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Senior High School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 03596, $6.25 member, $8.00 nonmember). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; Adolescents; Annotated Bibliographies; *Books; *Fiction; High Schools; Independent Reading; *Nonfiction; ReadingInterests; Reading Materials; *Recreational Reading ABSTRACT The books listed in this annotated bibliography, selected to provide pleasurable reading for high schoolstudents, are arranged alphabetically by author under 35 main categories:(1) adventure and adventurers; (2) animals; (3) art and architecture;(4) biography; (5) careers and people on the job; (6)cars and airplanes; (7) great books that are unusual; (8) drama; (9)ecology; (10) essays; (11) ethnic experiences; (12) fantasy; (13) history; (14) historical fiction; (15) hobbies and crafts; (16)horror, witchcraft, and the occult; (17) humor; (18) improving yourself; (19)languages; (20) love and romance; (21) music and musicians; (22)mystery and crime; (23) myths and legends; (24) philosophies andphilosophers; (25) poetry and poets; (26) social and personalproblems; (27) religion and religious leaders; (28) science andscientists; (29) science fiction; (30) short stories; (31)sports and sports figures; (32) television, movies, and entertainment; (33)wars, soldiers, spying, and spies; (34) westerns and people ofthe west; and (35) women. -

Picture-Book Professors Academia and Children's Literature

Edinburgh Research Explorer Picture-Book Professors Citation for published version: Terras, M 2018, Picture-Book Professors: Academia and Children's Literature . Elements in Publishing and Book Culture, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK . https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108529501 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1017/9781108529501 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 80.113.15.100, on 29 Oct 2018 at 19:02:17, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108529501 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 80.113.15.100, on 29 Oct 2018 at 19:02:17, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108529501 Elements in Publishing and Book Culture edited by Samantha Rayner University College London Rebecca Lyons University of Bristol PICTURE-BOOK PROFESSORS Academia and Children’s Literature Melissa M. -

Eagle Annual: the Best of the 1950S Comic Free Download

EAGLE ANNUAL: THE BEST OF THE 1950S COMIC FREE DOWNLOAD Daniel Tatarsky | 176 pages | 05 Aug 2008 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780752888941 | English | London, United Kingdom Second-hand Eagle Annual for sale on UK's largest auction and classifieds sites Russell added it Aug 05, Condition: new. Sort by highest price first. The front cover of the first Eagle Annual: The Best of the 1950s Comic of Eaglewith artwork by Frank Hampson. The original Dan Dare was no longer a feature of the comic, his eponymous great-great grandson taking on the mantle of space explorer instead. Children were encouraged to submit their good deeds to Eagle Annual: The Best of the 1950s Comic comic; those that had their stories printed were called MUGs, a not-so-subtle dig at the "spivs" who made fun of them. Jack and Jill Playhour. He and his team of artists posed for photographs, in the positions drawn in his pencil sketches Hampson usually posed for Dan Dare. Customers who bought this item also bought. James' Church in Birkdale. Dan Dare on Mars. Varah also accompanied Morris on tours of Cathedrals often filled with Eagle readers keen to meet the comic's creators. Cancel Notify me before the end of the auction. Brand new book. Item description we will always try to describe an item's condition accurately but do sometimes get it wrong. You will be required to submit damaged item and packaging for inspection. There is no proper series that can be tracked in the book nor a proper story. Book Depository hard to find London, United Kingdom. -

Monday 03 July 2017: 09.00-10.30

MONDAY 03 JULY 2017: 09.00-10.30 Session: 1 Great Hall KEYNOTE LECTURE 2017: THE MEDITERRANEAN OTHER AND THE OTHER MEDITERRANEAN: PERSPECTIVE OF ALTERITY IN THE MIDDLE AGES (Language: English) Nikolas P. Jaspert, Historisches Seminar, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg DRAWING BOUNDARIES: INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION IN MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC SOCIETIES (Language: English) Eduardo Manzano Moreno, Instituto de Historia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), Madrid Introduction: Hans-Werner Goetz, Historisches Seminar, Universität Hamburg Details: ‘The Mediterranean Other and the Other Mediterranean: Perspective of Alterity in the Middle Ages’: For many decades, the medieval Mediterranean has repeatedly been put to use in order to address, understand, or explain current issues. Lately, it tends to be seen either as an epitome of transcultural entanglements or - quite on the contrary - as an area of endemic religious conflict. In this paper, I would like to reflect on such readings of the Mediterranean and relate them to several approaches within a dynamic field of historical research referred to as ‘xenology’. I will therefore discuss different modalities of constructing self and otherness in the central and western Mediterranean during the High and Late Middle Ages. The multiple forms of interaction between politically dominant and subaltern religious communities or the conceptual challenges posed by trans-Mediterranean mobility are but two of the vibrant arenas in which alterity was necessarily both negotiated and formed during the medieval millennium. Otherness is however not reduced to the sphere of social and thus human relations. I will therefore also reflect on medieval societies’ dealings with the Mediterranean Sea as a physical and oftentimes alien space. -

Comics and Graphic Novels Cambridge History of The

Comics and Graphic Novels Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Volume 7: the Twentieth Century and Beyond Mark Nixon Comics – the telling of stories by means of a sequence of pictures and, usually, words – were born in Britain in the late nineteenth century, with Ally Sloper’s Half-Holiday (Gilbert Dalziel, 1884) and subsequent imitators. These publications were a few pages long, unbound, and cheap – and intended for working-class adult readers. During the twentieth century, bound books of picture stories developed in Europe and North America, and by the end of the century had become a significant factor in British publishing and popular culture. However, British comics scholarship has been slow to develop, at least relative to continental European and North American comics scholarship, although specialist magazines such as The Comics Journal, Comics International and Book & Magazine Collector have featured articles on British comics, their publishers and creators. Towards the end of the twentieth century, the work of Martin Barker and Roger Sabin began to shed new light on certain aspects of the history of British comics, a baton now being taken up by a few scholars of British popular culture1, alongside a growing popular literature on British comics2. 1 For a recent overview, see Chapman, James British comics: a cultural history (London, 2011). 2 Perhaps the best example of this is Gravett, Paul and Stanbury, Peter Great British comics (London, 2006). By the beginning of the twentieth century, Harmsworth dominated the comics market they had entered in 1890 with Comic Cuts and Illustrated Chips. Their comics provided the template for the industry, of eight-page, tabloid-sized publications with a mixture of one-panel cartoons, picture strips and text stories, selling at 1/2d. -

Provisional Programme-1

IGNCC 2018 WEDNESDAY 27 JUNE 2018 8.15–9.00 Registration (Coffee and pastries) 9.00 Welcome 9.15–10.15: Session 1 Keynote Chair: Chris Murray Rozi Hathaway (Cosmos, Njálla - Breakout Talent Award Winner, Broken Frontier Awards 2016) – Retrospective Storytelling: From Childhood to Characterisation 10.15–11.15: Session 2 Panel 2a – Trauma And Collective History Chair: Alexandra Alberda • Earle, Harriet – Family Memories And Collective Remembrance In Vietnamese–American Graphic Memoirs • Veld, Laurike in 't – A Past And Future (Im)Perfect: “Never Before” And “Never Again” In Representing The Rwandan Genocide Panel 2b – Fan Events and Activities Chair: Mel Gibson • Woo, Benjamin – Mapping Comic Con Events In North America • Chalifour, Spencer – Question Without An Answer: The Question’s Letter Columns As Cultural Memory Panel 2c – Approaching Comics Histories Chair: Ian Hague • De Dobbeleer, Michel – How To Structure Comics Histories? Belgium, Bulgaria, Europe And The World • Hibbett, Mark – Defining The Marvel Age: Pulse–Pounding Periodisation 11.15–11.45 Coffee 11.45–13.15: Session 3 Panel 3a – Trauma And Personal History Chair: Laurike in ’t Veld • Appleton, Catherine – Making Sense Of The Past: Using The Graphic Novel To Tell An Intergenerational Story And Represent Trauma • Vij, Aanchal – Survivor’s Guilt And Surviving The Guilt: Nostalgia, Jewishness And Sequential Art In Maus And The Amazing Adventures Of Kavalier And Clay • Mills, Rebecca – Figuring Fictions And Fractures: Trauma, Memory, And The Mystery Of Agatha Christie Panel 3b -

Forbidden Planet Catalogue

Forbidden Planet Catalogue Generated 28th Sep 2021 TS04305 Batman Rebirth Logo T-Shirt $20.00 Apparel TS04301 Batman Rebirth Logo T-Shirt $20.00 TS04303 Batman Rebirth Logo T-Shirt $20.00 Anime/Manga T-Shirts TS04304 Batman Rebirth Logo T-Shirt $20.00 TS04302 Batman Rebirth Logo T-Shirt $20.00 TS19202 Hulk Transforming Shirt $20.00 TS21001 Black Panther Shadow T Shirt $20.00 TS06305 HXH Gon Hi T-Shirt $20.00 TS10801 Black Spider-punk T-Shirt $20.00 TS11003 Marvel Zombies T-Shirt $20.00 TS10804 Black Spider-punk T-Shirt $20.00 TS11004 Marvel Zombies T-Shirt $20.00 TS10803 Black Spider-punk T-Shirt $20.00 TS11002 Marvel Zombies T-Shirt $20.00 TS01403 BPRD T-Shirt $20.00 TS11001 Marvel Zombies T-Shirt $20.00 TS01401 BPRD T-Shirt $20.00 TS15702 Mega Man Chibi T-Shirt $20.00 TS01402 BPRD T-Shirt $20.00 TS15704 Mega Man Chibi T-Shirt $20.00 TS01405 BPRD T-Shirt $20.00 TS15705 Mega Man Chibi T-Shirt $20.00 TS01404 BPRD T-Shirt $20.00 TS15703 Mega Man Chibi T-Shirt $20.00 TS15904 Cable T-Shirt $20.00 TS15701 Mega Man Chibi T-Shirt $20.00 TS15901 Cable T-Shirt $20.00 TS13505 Captain Marvel Asteroid T-Shirt $20.00 Comic T-Shirts TS13504 Captain Marvel Asteroid T-Shirt $20.00 TS03205 Carnage Climbing T-Shirt $20.00 TS05202 Alex Ross Spider-Man T-Shirt $20.00 TS03204 Carnage Climbing T-Shirt $20.00 TS05203 Alex Ross Spider-Man T-Shirt $20.00 TS03202 Carnage Climbing T-Shirt $20.00 TS05201 Alex Ross Spider-Man T-Shirt $20.00 TS03201 Carnage Climbing T-Shirt $20.00 TS05204 Alex Ross Spider-Man T-Shirt $20.00 TS03904 Carnage Webhead T-shirt Extra Large -

Abstracts and Delegate Information Now Available

Page 1 13/09/2007 Reassessing the Aesthetics of Trash 28th and 29th August 2007 Abstracts and delegate information Name Title and abstract Institution, biography and research, contact details Matthew I can do that: Adventures in British small press comics Matthew Badham is a freelance writer who writes Badham exclusively about comics. His main interest is in the In 2006, Matt Smith, the editor of British science fiction comics 2000AD and state of small comics presses in Britain. the Judge Dredd Megazine, wrote that with both those titles ‘being the only non-juvenile British newsstand comics still around’, the best chance for Email: [email protected] prospective writers and artists to make inroads into comics was to contribute to an independent, small press publication. Smith’s assertion confirmed what many comics fans and professionals already knew: that while the British Comics Scene (it could no longer be described as an industry due to the paucity of available titles) was in a dire state, British small press comics were thriving. This paper will put forward a working definition of a small press comic, a self- published comic created for reasons other than profit, discuss the pre- conditions that led to the current state of the British Comics Scene and give an overview of the British small press. Along the way it will discuss the late-80’s, early-90’s exodus of British creators to America, reference the ‘real mainstream’ theory* as expounded by prominent comics retailer Steve Holland and celebrate the diversity of product available in the small press. Primary data will be used throughout this paper, specifically interviews conducted with small pressers. -

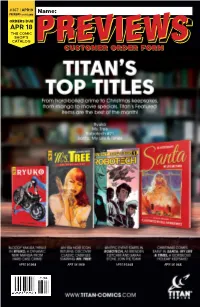

Apr 18 Customer Order Form

#367 | APR19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE APR 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM APR191968 APR191969 APR191958 APR191988 CUSTOMER 601 7 Apr19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 3/7/2019 3:12:08 PM KNOW... BEFORE YOU GO. Watch every Wednesday @ 4:00 pm EST / 1:00 pm PST previewsworld.com/PREVIEWSworldWeekly PLUS: Tune in for ToyChest’s Talking Toys with Natasha to learn about new toys and collectibles hitting comic shops each week! previewsworld.com/talkingtoys PREVIEWS World WeeklyOF.indd 1 3/7/2019 11:20:24 AM THUMBS #1 TRANSFORMERS/ IMAGE COMICS GHOSTBUSTERS #1 IDW PUBLISHING EVENT LEVIATHAN #1 DC COMICS THE RIDE: BURNING DESIRE #1 SILVER SURFER: IMAGE COMICS BLACK #1 MARVEL COMICS SUPERMAN: YEAR ONE #1 DC COMICS/ DC BLACK LABEL RED SONJA: DISNEY FROZEN: BIRTH OF THE HERO WITHIN #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE SHE-DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT USAGI YOJIMBO #1 IDW PUBLISHING DISNEY: SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN DWARFS #1 MIGHTY MORPHIN DARK HORSE COMICS POWER RANGERS #40 BOOM! STUDIOS Apr19 Gem Page.indd 1 3/7/2019 3:20:44 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Aftershock Shock Volume 2 HC l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Steel Cage #1 l AHOY COMICS Princess of Venus #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Jughead: Time Police #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Stitched: Terror #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC The No Ones #1 l CAVE PICTURES PUBLISHING My Teacher Is a Robot Picture Book l CROWN BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS 1 All Quiet on the Western Front GN l DEAD RECKONING Little Lulu Volume 1: Working Girl HC l DRAWN & QUARTERLY 1 The Monster Art of Basil Gogos SC/HC l FANTACO ENTERPRISES INC.