2. the Humanitarian Aid Workers 34 2.1 Emerging Research on Humanitarian Aid Workers 34 2.2 the Objectives of the Study 38 2.3 Methodology 56

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

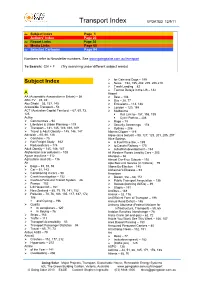

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11

Transport Index UPDATED 12/9/11 [ Subject Index Page 1 [ Authors’ Index Page 23 [ Report Links Page 30 [ Media Links Page 60 [ Selected Cartoons Page 94 Numbers refer to Newsletter numbers. See www.goingsolar.com.au/transport To Search: Ctrl + F (Try searching under different subject words) ¾ for Cats and Dogs – 199 Subject Index ¾ News – 192, 195, 202, 205, 206,210 ¾ Trash Landing – 82 ¾ Tarmac Delays in the US – 142 A Airport AA (Automobile Association in Britain) – 56 ¾ Best – 108 ABC-TV – 45, 49 ¾ Bus – 28, 77 Abu Dhabi – 53, 137, 145 ¾ Emissions – 113, 188 Accessible Transport – 53 ¾ London – 120, 188 ACT (Australian Capital Territory) – 67, 69, 73, ¾ Melbourne 125 Rail Link to– 157, 198, 199 Active Cycle Path to – 206 ¾ Communities – 94 ¾ Rage – 79 ¾ Lifestyles & Urban Planning – 119 ¾ Security Screenings – 178 ¾ Transport – 141, 145, 149, 168, 169 ¾ Sydney – 206 ¾ Travel & Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 Alberta Clipper – 119 Adelaide – 65, 66, 126 Algae (as a biofuel) – 98, 127, 129, 201, 205, 207 ¾ Carshare – 75 Alice Springs ¾ Rail Freight Study – 162 ¾ A Fuel Price like, – 199 ¾ Reduced cars – 174 ¾ to Darwin Railway – 170 Adult Obesity – 145, 146, 147 ¾ suburban development – 163 Afghanistan (car pollution) – 108 All Western Roads Lead to Cars – 203 Agave tequilana – 112 Allergies – 66 Agriculture (and Oil) – 116 Almost Car-Free Suburb – 192 Air Alps Bus Link Service (in Victoria) – 79 ¾ Bags – 89, 91, 93 Altona By-Election – 145 ¾ Car – 51, 143 Alzheimer’s Disease – 93 ¾ Conditioning in cars – 90 American ¾ Crash Investigation -

2017: Fight Card and Results: Events 386 to 424

2017: Fight Card and Results: Events 386 to 424 Event 424 UFC 219: Cyborg vs. Holm December 30, 2017 Las Vegas, Nevada Weight Winner Loser Method Round Time Women's Featherweight Championship Women's Feather Cris Cyborg © Holly Holm Decision (unanimous) (49‐46, 48‐47, 48‐47) 5 5:00 Lightweight Khabib Nurmagomedov Edson Barboza Decision (unanimous) (30‐25, 30‐25, 30‐24) 3 5:00 Lightweight Dan Hooker Marc Diakiese Submission (guillotine choke) 3 0:42 Women's Straw Carla Esparza Cynthia Calvillo Decision (unanimous) (29‐28, 29‐28, 29‐28) 3 5:00 Welterweight Neil Magny Carlos Condit Decision (unanimous) (30‐27, 30‐27, 29‐28) 3 5:00 Light Heavyweight Michał Oleksiejczuk Khalil Rountree Jr. Decision (unanimous) (30‐27, 30‐27, 30‐27) 3 5:00 Featherweight Myles Jury Rick Glenn Decision (unanimous) (30‐27, 30‐27, 30‐27) 3 5:00 Middleweight Marvin Vettori Omari Akhmedov Draw (majority) (28‐28, 29‐28, 28‐28) 3 5:00 Flyweight Matheus Nicolau Louis Smolka Decision (unanimous) (30‐26, 30‐26, 30‐25) 3 5:00 Bantamweight Tim Elliott Mark De La Rosa Submission (anaconda choke) 2 1:41 For the UFC Women's Featherweight Championship. Event 423 UFC on Fox 26: Lawler vs. dos Anjos December 16, 2017 Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada Weight Winner Loser Method Round Time Welterweight title eliminator Welterweight Rafael dos Anjos Robbie Lawler Decision (unanimous) (50‐45, 50‐45, 50‐45) 5 5:00 Catchweight 148.5 lb Josh Emmett Ricardo Lamas KO (punch) 1 4:33 Welterweight Santiago Ponzinibbio Mike Perry Decision (unanimous) (29‐28, 29‐28, 29‐28) 3 5:00 Light Heavyweight -

Ufc Welterweight Champion Tyron Woodley and Retired Vet Yves Edwards Join Host Karyn Bryant for Fs1 Ufc Fight Night: Werdum Vs

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: John Stouffer Wednesday, Nov. 15, 2017 [email protected] UFC WELTERWEIGHT CHAMPION TYRON WOODLEY AND RETIRED VET YVES EDWARDS JOIN HOST KARYN BRYANT FOR FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: WERDUM VS. TYBURA THIS SATURDAY Former Welterweight Contender Dan Hardy and John Gooden Call Fights Live from Sydney, Australia LOS ANGELES – Today, FOX Sports announces welterweight champion Tyron Woodley (@twooodley) and retired vet Yves Edwards (@thugjitsumaster) work as analysts in FOX Sports’ Los Angeles studio with host Karyn Bryant (@KarynBryant) for FS1 UFC FIGHT NIGHT: WERDUM VS. TYBURA on Saturday, Nov. 18. In addition, Dan Hardy (@danhardymma) joins blow-by-blow announcer John Gooden (@JohnGoodenUK) to call the bouts Octagon-side from Sydney, Australia. Heidi Androl (@HeidiAndrol) adds reports and interviews fighters onsite. Victor Davila (@mastervic10) and Marlon Vera (@chitoveraUFC) have the call in Spanish on FOX Deportes. In the five-round main event, former heavyweight champion and No. 2-ranked Fabricio Werdum (21-7-1) faces No. 8 Marcin Tybura (16-2). FOX UFC analyst Kenny Florian believes Werdum’s jiu-jitsu skills give him the edge in the fight. “Werdum is probably in my top three as far as best grapplers to ever compete in the Octagon. He’s one of the finest submission experts you’ll ever see. Fabricio is very confident right now, coming off a quick turnaround. He wants the fight right now, which shows he’s very motivated to get that belt back.” Watch the preview from Saturday’s UFC FIGHT NIGHT POSTFIGHT SHOW here. Coverage begins on Friday, Nov. 17 (7:00 PM ET) with the FS1 UFC WEIGH-IN SHOW with Bryant, Woodley and Edwards in studio and Androl reporting onsite. -

Expanded HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

Zablotska et al. BMC Public Health (2018) 18:210 DOI 10.1186/s12889-017-5018-9 STUDY PROTOCOL Open Access Expanded HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) implementation in communities in New South Wales, Australia (EPIC-NSW): design of an open label, single arm implementation trial Iryna B. Zablotska1* , Christine Selvey2, Rebecca Guy1, Karen Price3, Jo Holden2, Heather-Marie Schmidt2, Anna McNulty4, David Smith5, Fengyi Jin1, Janaki Amin1,6, David A. Cooper1, Andrew E. Grulich1*, on behalf of the EPIC-NSW study group Abstract Background: The New South Wales (NSW) HIV Strategy 2016–2020 aims for the virtual elimination of HIV transmission in NSW, Australia, by 2020. Despite high and increasing levels of HIV testing and treatment since 2012, the annual number of HIV diagnoses in NSW has remained generally unchanged. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is highly effective in preventing HIV infection among gay and bisexual men (GBM) when taken appropriately. However, there have been no population-level studies that evaluate the impact of rapid PrEP scale-up in high-risk GBM. Expanded PrEP Implementation in Communities in NSW (EPIC-NSW) is a population-level evaluation of the rapid, targeted roll-out of PrEP to high-risk individuals. Methods: EPIC-NSW, is an open-label, single-arm, multi-centre prospective observational study of PrEP implementation and impact. Over 20 public and private clinics across urban and regional areas in NSW have participated in the rapid roll-out of PrEP, supported by strong community mobilization and PrEP promotion. The study began on 1 March 2016, aiming to enroll at least 3700 HIV negative people at high risk of HIV. -

Weightlifting Booklet

The De La Salle College Weightlifting Story Forward - by Dave Hale In compiling this booklet, I feel that the De La Salle Weightlifting Story needs to be told. Amazingly, the sport was introduced by a young student, Adrian Kebbe, in 1974. Over the next forty years, the sport has grown and prospered, with De La Salle providing an assembly line of future champions. Over this time, the College has dominated the State competitions and shown itself to be the best weightlifting school in the State and arguably the Nation. The De La Salle Weightlifting Story The story begins in the Blue and Gold of 1975 and I quote “In February, this year, Adrian Kebbe, a new boy to the school decided to form a school weightlifting team”. This team comprising 14 senior lifters won the Schoolboys Weightlifting Perpetual Trophy in August. By 1976, the team had grown to 31 lifters with Adrian Kebbe as Captain. The Hawthorn Citizens Youth Club Sponsors Adrian and a link is made. The College is State Champions by 25 points and 60 members represent the College through A to E Grades. The team’s success continues in 1977 as De La Salle defends its title. Two lifters Mark Shanahan and Brendan Webster represent Victoria at the nationals (for a silver and bronze). Br. Michael Feenan has been coerced into role as Manager and Adrian continues as Captain/Coach. The team has several younger members and Paul Coffa is thanked for his support and guidance. 1978 is another successful year as De La retains its trophy despite injuries and renovations to the gym. -

Rick Hart - Proudly Supporting Your Local RSL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE feBRUARY 2008 VOL. 31 no.1 The official journal of The ReTuRned & SeRviceS League of austraLia POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListening Branch incorporated • Po Box 3023 adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • established 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL first VC winner to be honoured Page 5 RSL Australia australia day awards Pages 12 & 13 Day Awards Top left, Peter Douglas receiving his award from RSL President, Mr William Gaynor. Above; Dr Steffan Silcox making his thank-you speech.Left; (Digger) Cleak OAM and Laurie Fraser MBE from Albany receiving their awards. from the Services An Australian Day presentation of medallions was held Mr Gaynor (President RSL WA) said “that this years recipients of Australian Pages Day Achievement Awards had again shown a level of commitment to our 16 to 18 at ANZAC House on 25th January, 2008. The medallions are presented annually for service to members and organisations ideals from both members and the community with the following being that have promoted RSL principles and ideals. worthy recipients of the RSL Medallions for 2008”. Continue Page 9 Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL Osborne Park 9445 5000 Midland 9267 9700 Belmont 9477 4444 O’Connor 9337 7822 Claremont 9284 3699 East Vic Park Superstore 9470 4949 Joondalup 9301 4833 Perth City Mega Store 9227 4100 Mandurah 9535 1246 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. Just show your membership card! I put my name on it.” 2 The Listening Post february 2008 www.northsidenissan.com.au ☎ 14 BERRIMAN DRIVE, WANGARA 9409 0000 ALL NEW MICRA ALL NEW DUALIS 5 DOOR AUTO IS 2 CARS IN 1! • IN 10 VIBRANT COLOURS • HATCH AGILITY • MAKE SURE YOU WASH • SUV VERSATILITY SEPARATELY • SLEEK - STYLISH DUALIS REGISTER YOUR INTEREST REGISTER YOUR INTEREST OR YOU’LL MISS OUT. -

09-10-Swim-Guide.Pdf

Carolina Swimming and Diving • General Information 2009-10 Table of Contents All-Americas, NCAA Qualifiers & All-ACC Honorees . Front Cover 2008-09 Team Pictures in Color . Inside Front Cover General Information . 1 2009-10 Women’s Roster. 2 2009-10 Men’s Roster . 3 2009-10 Women’s Season Preview . 4 2009-10 Men’s Season Preview. 5 2009-10 Preseason Men’s Depth Chart . 6 2009-10 Preseason Women’s Depth Chart . 7 2008-09 Final Men’s Depth Chart. 8 2008-09 Final Women’s Depth Chart . 9 2009-10 Schedule, 2008-09 Team Results, Koury Natatorium Information . 10 General Carolina Athletic Department Information . 11 Head Coach Rich DeSelm . 12 Diving Coach Kevin Lawrence . 15 Chief Assistant Coach Mike Litzinger . 16 Assistant Coach Eric Stefanski . 17 Assistant Coaches Christy Garth & Sean Quinn . 18 2009-10 North Carolina Swimming & Diving Quick Facts Assistant Coaches Griff Helfrich & Jon Fox, Location: Chapel Hill, N.C. Carolina Swimming Support Staff. 19 Established: December 11, 1789 2009-10 Tar Heel Men’s Swimming & Diving Biographies . 20 Enrollment: 28,136 (17,895 undergraduates, 8,275 postgraduates) 2009-10 Tar Heel Women’s Swimming & Diving Biographies . 36 Chancellor: Dr. Holden Thorp 2009-10 Team Pictures in Black & White . 50 Director of Athletics: Dick Baddour Senior Associate Athletic Director for Olympic Sports: Dr. Beth Miller Great Moments in Carolina Swimming & Diving History . 51 National Affiliation: NCAA Division I Carolina Swimming History and Tradition . 54 Conference: Atlantic Coast Conference All-Americas . 60 Nickname: Tar Heels ACC Champions. 63 Mascot: Rameses the Ram (Both Live and Costumed) Conference Award Winners . -

The Pulse August 2019.Pdf

BRINGING MEDICAL HUMANITARIAN ACTION TO YOU AUGUST 2019 SPECIAL EDITION MSF AUSTRALIA 25TH ANNIVERSARY IN FOCUS FIELD WORKER STORIES FROM 1994 TO 2019 3 EDITORIAL: ALWAYS EVOLVING 4 NEWS IN BRIEF 5 25 YEARS: THE FOUNDATIONS 6 25 YEARS: THE SYDNEY MEDICAL UNIT CHAMPIONING AUGUST 2019 8 25 YEARS: UNCONVENTIONAL APPROACHES WOMEN'S AND 10 25 YEARS: FIELD WORKER STORIES MSF.ORG.AU CHILDREN'S 19 A LEGACY WITHOUT BORDERS HEALTH CONTENTS ABOUT MÉDECINS SANS FRONTIÈRES Médecins Sans Frontières is an international, independent, medical humanitarian organisation that was founded in France in 1971. The organisation delivers emergency medical aid to people affected by armed conflict, epidemics, exclusion from healthcare and natural disasters. Assistance is provided based on need and irrespective of race, religion, gender or political affiliation. When Médecins Sans Frontières witnesses serious acts of violence, neglected crises, or obstructions to its activities, the organisation may speak out about this. Today, Médecins Sans Frontières is a worldwide movement of 24 associations, including one in Australia. In 2018, 217 field positions were filled by Australians and New Zealanders. THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT This special issue of The Pulse marks 25 years of Médecins Sans Frontières Australia. Over the past quarter- century, our organisation has made an invaluable contribution to the global medical-humanitarian movement – and it is your incredible generosity that has enabled us to do so. The ongoing loyalty and trust of individuals like you allow us to maintain our independence and to stay impartial, to reach the people who need our care – and to speak out on behalf of our patients. -

Registration Brochure

New worlds Come explore ANZCA ASM Registration April 29 – May 3, 2019 Kuala Lumpur brochure Convention Centre, Malaysia asm.anzca.edu.au #ASM19KL Contents ASM Regional Organising Key 2019 meeting dates Social media guidelines Committee Abstract submissions close Social media guidelines 1 January 27 Co-Convenor/Emerging Leaders Conference All sessions are “open” for tweeting and facebooking by default. However, speakers can explicitly Invitation from the co-convenors 2 Co-Convenor Abstract notification to authors request that certain talks, slides, or findings – particularly where content is confidential or sensitive Early March – be left out of the social media conversation, and some sessions may be completely closed. The Invitation from the president and dean 3 Dr Joanne Samuel @Joannedsamuel session chairs will provide clear instructions at the beginning of each talk to highlight any such Co-Convenor/Scientific Convenor Authors confirm participation Keynote speakers 4 requests. Please respect the wishes of your peers and colleagues in this regard. Please also keep Dr Colin Chilvers March 17 College Ceremony Orator 8 your social media conversations collaborative and respectful. Deputy Scientific Co-Convenor/ePoster Convenor Deadline for registration by presenters Invited speakers 8 Dr Peter Wright March 17 Twitter and Facebook Did you miss that session Industry supported speakers 9 Deputy Scientific Co-Convenor Early-bird registrations close Dr Clare McArthur March 17 Pre-meeting workshops 10 We’ll be using Twitter in Kuala Lumpur, and we’d everyone is talking about? FPM Scientific Convenor Emerging Leaders Conference love as many of our speakers and delegates to Log on to the Virtual ASM asm.anzca.edu.au/ Workshops, masterclasses and small Dr Chris Orlikowski April 26-28 be part of the buzz. -

December 2020 ISSN 1080-6040

® December 2020 December Paper folding book, 12 folios, Paper 2 lines per side, black ink, Thai script. 14.2 in x 4.7 UK.London, Domain. in / 27.31 cmPublic x 28.57 cm. British Library, Zoonotic Infections Artist Unknown. Cat treatise (Tamra maeo), 1800–1870.Artist Unknown. Cat treatise (Tamra DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Mailstop D61, Atlanta, GA 30329-4027 Official Business Penalty for Private Use $300 Return Service Requested ISSN 1080-6040 Peer-Reviewed Journal Tracking and Analyzing Disease Trends Pages 2799–3122 ® EDITOR-IN-CHIEF D. Peter Drotman ASSOCIATE EDITORS EDITORIAL BOARD Charles Ben Beard, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA Barry J. Beaty, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA Ermias Belay, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Martin J. Blaser, New York, New York, USA David M. Bell, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Andrea Boggild, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Sharon Bloom, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Christopher Braden, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Richard Bradbury, Melbourne, Australia Arturo Casadevall, New York, New York, USA Mary Brandt, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Kenneth G. Castro, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Corrie Brown, Athens, Georgia, USA Vincent Deubel, Shanghai, China Charles H. Calisher, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA Christian Drosten, Charité Berlin, Germany Benjamin J. Cowling, Hong Kong, China Anthony Fiore, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Michel Drancourt, Marseille, France Isaac Chun-Hai Fung, Statesboro, Georgia, USA Paul V. Effler, Perth, Australia Kathleen Gensheimer, College Park, Maryland, USA David O. Freedman, Birmingham, Alabama, USA Rachel Gorwitz, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Peter Gerner-Smidt, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Duane J. Gubler, Singapore Stephen Hadler, Atlanta, Georgia, USA Richard L. Guerrant, Charlottesville, Virginia, USA Matthew J. -

Victoria Government Gazette by Authority of Victorian Government Printer

Victoria Government Gazette By Authority of Victorian Government Printer UNCLAIMED MONEYS ACT 1962 N–Z P 2 (Vol. 2 of 2) Friday 31 October 2008 www.gazette.vic.gov.au PERIODICAL ii P2 (Vol. 2 of 2) 31 October 2008 Victoria Government Gazette TABLE OF PROVISIONS Unclaimed Moneys Page National Can Industries Limited 445 Natoli Howell Lawyers 445 Navigator Australia Ltd – Aviva 446 Nevin Lenne & Gross 452 Newcrest Mining Limited 452 Nufarm Limited 453 Nufarm Limited 453 Oakton Limited 454 OAMPS Limited 455 O’Farrell Robertson McMahon 457 Orica Limited 458 Orica Limited 466 Origin Energy Limited 472 Over Fifty Group Limited 478 Oxiana Limited 481 Oxiana Limited 481 Pacifica Group Limited 482 Pacific Brands Limited 483 Pacific Brands Limited – NZ Dollars 485 Paperlinx Limited 485 Perpetual Trustee Company Ltd 486 Perry Weston Lawyers 486 Phillips Fox 487 Peter Butcher & Associates 487 Philip Morris Limited 487 Philip Webb 488 Plantation Land Limited 488 Plaza Legal 489 Premium Investors Limited 489 Prime Financial Group Limited 490 Programmed Maintenance Services Limited 491 Pro Medicus Limited 492 RACV Finance Limited 492 RACV Limited 493 Red Energy 493 Residential Tenancies Bond Authority 494 Rio Tinto Limited 533 Rio Tinto Limited – Pounds Sterling 548 Robert V. Gardner – Solicitor 552 RT Edgar (Toorak) Pty Ltd 553 Russell Kennedy Pty Ltd 553 Victoria Government Gazette P2 (Vol. 2 of 2) 31 October 2008 iii Sam Pennisi Property Management 553 Sandhurst Trustees 554 Seek Limited 554 Select Harvests Limited 555 Sensis Pty Ltd 556 Service Stream -

Quarterly Edition, April 2019 Art, Words and Photos from Central Australian

Art, words and photos from Central Australian Aboriginal Art Centres Quarterly edition, April 2019 THE DESART RADAR Desert River Sea: Portraits of the Kimberley In 2018 Warlayirti Artists were commissioned to create glass panels for the Art Gallery of Western Australia’s Desert River Sea project. Warlayirti Artists' Christine Yukenbarri, Frances Nowee, Imelda Yukenbarri Gugaman and Miriam Baadjo attended the opening in Perth in February, presenting artist talks and signing books. Waralyirti Artists were the first art centre to work in fused glass when it began working in Bullseye coloured glass in 2001 following the construction of an on-site glass studio. Despite the glass studio not being used for over 10 years, the artists had revived the medium for the Desert River Sea 2019 Exhibition where artists created individual panels as well as a collaborative piece on the theme of bush tucker. (Top left): Christine Yukenbarri with her name & artwork in lights in Perth CBD’s Yagan Square. Image: Warlayirti Artists (Top right): Desert River Sea: Portraits of the Kimberley opening day celebration at AGWA, Sat 9 Feb 2019. Christine Yukenbarri signing the Desert River Sea publication. Image: Rebecca Mansell, courtesy AGWA (Bottom right): Desert River Sea: Portraits of the Kimberley opening day celebration at AGWA, Sat 9 Feb 2019. Imelda Yukenbarri Gugaman, Christine Yukenbarri, Frances Nowee & Miriam Baadjo (Warlayirti Artists) with artworks Bush Tucker on Country. Image: Rebecca Mansell, courtesy AGWA Panjiti McKenzie OAM. Image: Rhett Hammerton / NPY Women's Council Women's / NPY Hammerton Rhett Image: McKenzie OAM. Panjiti Artist Pantjiti Unkari McKenzie awarded the Order of Australia Medal.