Missorts Volume II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 122 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 SupergrassSupergrassSupergrass on a road less travelled plus 4-Page Truck Festival Review - inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] THE YOUNG KNIVES won You Now’, ‘Water and Wine’ and themselves a coveted slot at V ‘Gravity Flow’. In addition, the CD Festival last month after being comes with a bonus DVD which picked by Channel 4 and Virgin features a documentary following Mobile from over 1,000 new bands Mark over the past two years as he to open the festival on the Channel recorded the album, plus alternative 4 stage, alongside The Chemical versions of some tracks. Brothers, Doves, Kaiser Chiefs and The Magic Numbers. Their set was THE DOWNLOAD appears to have then broadcast by Channel 4. been given an indefinite extended Meanwhile, the band are currently in run by the BBC. The local music the studio with producer Andy Gill, show, which is broadcast on BBC recording their new single, ‘The Radio Oxford 95.2fm every Saturday THE MAGIC NUMBERS return to Oxford in November, leading an Decision’, due for release on from 6-7pm, has had a rolling impressive list of big name acts coming to town in the next few months. Transgressive in November. The monthly extension running through After their triumphant Truck Festival headline set last month, The Magic th Knives have also signed a publishing the summer, and with the positive Numbers (pictured) play at Brookes University on Tuesday 11 October. -

Happy New Year!

Advertise instantly via www.dailyinfo.co.uk [email protected] QR CODES Scan these Oxford’s 01865 241133 (Mon-Fri, 9am-6pm) with your phone’s QR code 1st floor of 121 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1HU app to go straight to these DAILY Line ads @ 50p/word. (min. 10) + VAT ads on dailyinfo.co.uk PROPERTY Box ads @ £10-£12/cm. (min. 3cm) + VAT JOBS INFO www.dailyinfo.co.uk HOUSES & FLATS TO LET Issue No. 8370 Next issue: Tue 8th Jan. Deadline: 10am, Mon 7th Jan RECRUITING: Fri 4th 2012 - Mon 7th Jan 2013 (Oxford Uni Christmas vac) WEEKEND SUPERVISOR Assessment Coordinator (must have managerial experience) This role, in the Test Development Unit (TDU), was IMMEDIATE START WHAT’S ON established to help achieve the operational objectives Must commit to a minimum of 1 year’s contract. in producing online tests. You will be required to Apply with CV to: [email protected] ensure the effective running of TDU operations, assist GREET THE NEW YEAR WITH AN Emperor String in the promotion of the TDU, support the development www.goingloco.com INVIGORATING YOGA WORKSHOP of IT systems and provide a high level of customer Quartet service. Educated to degree level, or with appropriate with renowned Astanga Yoga Britten String Quartet no.3 experience, you will be confident working with a range PART TIME TELESALES of software packages, have strong attention to detail, teacher Richard Adamo Oxford Tickets: Playhouse 01865 305305 / 07518 479062 STUDENTS WELCOME! Friday 5th & Saturday 6th January Coffee Holywell Music Room be well-organised and have high-level interpersonal We are an independent publisher for the global water Concerts skills. -

The Trinity Centre Conservation, Management & Maintenance Plan

Trinity Centre Conservation Project Conservation, Management & Maintenance Plan HLF HG-14-10203 The Trinity Centre Conservation, Management & Maintenance Plan Version 3 – October 2016 who wrote the plan and when Written by: Emma Harvey, Centre Manager, Trinity Community Arts Corinne Fitzpatrick, Ferguson Mann Architects Trinity Community Arts Trinity Centre Trinity Road Bristol BS2 0NW Page 1 of 47 Trinity Community Arts Ltd Registered Charity number 1144770 Registered Company Number 4372577 Trinity Centre Conservation Project Conservation, Management & Maintenance Plan HLF HG-14-10203 Contents 1 Introduction.......................................................3 5.9 Training.....................................................................21 1.1 Overview....................................................................3 6 Risks...............................................................23 1.2 about the authors.......................................................3 6.1 Risk Register............................................................23 1.3 Scope.........................................................................4 6.2 Key risks to our heritage...........................................23 1.4 Project summary........................................................5 Governance..............................................................23 2 Understanding Our Heritage.............................6 People......................................................................24 2.1 History of the Trinity Centre........................................6 -

Annual Report 2016/2017

TRINITY COMMUNITY ARTS ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 Registered Charity no.1144770 Limited Company no.4372577 1 ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 CONTENTS ARTS WELCOME FROM OUR CHAIR .........................................3 KEY ACHIEVEMENTS 2016/2017 .....................................5 7 MEMORABLE MOMENTS ................................................6 ARTS Arts West Side .....................................................................8 IGNiTE Programme ...........................................................10 Beyond IGNiTE .................................................................12 COMMUNITY Music ................................................................................13 COMMUNITY Trinity Community Initiative ..............................................16 Trinity Community Garden ................................................17 Venue Hire .........................................................................19 15 Trinity’s Partnerships ..........................................................21 EDUCATION Youth Music Programme ...................................................23 HERITAGE Trinity Centre Conservation Project ...................................27 - Community Consultation ................................................28 - Activities Programme ......................................................29 EDUCATION HERITAGE - Capital Repairs ................................................................30 - Project Status ..................................................................31 22 26 FINANCE -

Embodied Minstrelsy, Racialization and Redemption in Reggae

Haynes, J. (2019). Embodied minstrelsy, racialization and redemption in reggae. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(5-6), 996-1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419847111 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1177/1367549419847111 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Sage at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1367549419847111 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Embodied Minstrelsy, Racialization and Redemption in Reggae Abstract This article is a case study1 of a local reggae DJ (Derek) lauded for transgressing musical and ethnic boundaries and produced through discourses of racialized authenticity as flexible and heroic. While DJ Derek’s ethnically stylized performance could be construed as embodied minstrelsy, other aspects of his musical capital were equally significant in the localized context and were drawn into a wider dialogue of sustainability and collective belonging defined by Caribbean migrants. I argue that ambiguous cultural figures such as Derek have an organic, productive role within local music cultures, positioned at intergenerational moments in the process of identification and belonging for ethnically diverse audiences/producers and in this case where the cultural geography of music tastes are becoming embedded within a complex set of relations among local, national and transnational cultures. -

Rocksteady the Roots of Reggae 320 KBPS 2010Rar

Rocksteady - The Roots Of Reggae 320 KBPS 2010.rar 1 / 4 Rocksteady - The Roots Of Reggae 320 KBPS 2010.rar 2 / 4 3 / 4 Jamaica's extraordinary musical legacy, from ska to dub, Bob Marley to The Bug.. 21 Mar 2018 . Rocksteady - The Roots Of Reggae 320 KBPS 2010.rar.. Play On Mr Music - a 70s Roots Reggae Mix by BMC - *Play On Mr.. 15-01-2019 · reggae roots download reggae roots reggae do Roots ... Reggae Gold mediafire links free download, download Reggae Gold 2008 CD1, ... style that originated following on the development of ska and rocksteady.. The term "reggae," often used to describe any music coming from Jamaica, ... Rock steady, the next form the island developed, is the precursor to the ... as the politically and culturally directed music that followed it called roots. ... Thanks a lot to http://rippammell.blogspot.com for bringing this tune to my ears.. New classic jazz albums and compilation Download FLAC music genres Soul, ... JAZZ / FUNK JAZZ / ACID JAZZ / LOUNGE Wendell B - Southern Soul (2010). ... Jam Band Origin: USA Released: 2015 Quality: mp3, CBR 320 kbps Tracklist: 01. ... Jamaica: Rocksteady, Soul and Early Reggae at Studio One × Mes favoris.. Download The Rock Steady Riddim Produced By SmartKid Records Reggae & Black ... style that was mentioned in the Alton Ellis song "Rock Steady". rar from mediafire. ... Reggae and its roots: Ska, Rock Steady, Dub, Dance Hall and more. ... hit reggae and dancehall riddims released between the years 2000 and 2010.. - *LION YOUTH - Rat A Cut Bottle* Faixa: Rat A Cut Bottle And Dub Link para download: http://www.mediafire.com/file/t2g1c4yhskuy7fk/12_Lion_Youth_-_Rat_a... -

April 2016 / Issue No

“...the last two visits we have Time to been told to stand on the line with our hands behind our take backs and to let the dogs jump up on us” politics out Kerry - a prisoner’s wife Mailbag // page 7 of prisons “the planning and carrying Erwin James talks to Lord out of the job were the National Newspaper for Prisoners & Detainees Premiership, the afters and Woolf as he steps down getaway plan were strictly a voice for prisoners since as chair of the Prison Sunday pub league” April 2016 / Issue No. 202 / www.insidetime.org / A ‘not for profi t’ publication / ISSN 1743-7342 Reform Trust Noel Smith An average of 60,000 copies distributed monthly Independently verifi ed by the Audit Bureau of Circulations Comment // page 15 Comment // page 24 Prisons: A New Direction Slash and burn policy will place education and work l More time out of cell l Increased use of ROTL skills at the heart of the Justice Secretary’s vision for l Governor’s discretion to design IEP scheme l IPP prisoners to have ‘clear paths to exit’ a more effective and humane prison system l Fewer Recalls In this exclusive and historic interview Michael Gove MP reveals how he was ‘shocked’ by everything he saw during one prison visit and explains that among the fundamental changes he intends to introduce are autonomy for Governors and prison league tables. An avid reader of Inside Time, he also tells of his high regard for “the unvar- nished truth” he reads each month in our universally popular Mailbag section. -

Issue 120.Pmd

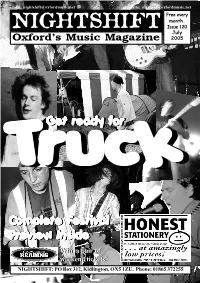

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 120 July Oxford’s Music Magazine 2005 GetGetGetGet rrrreadeadeadeadyyyy ffffoooorrrr TTTTTTrurururururuckckckckckck CCCCoooommmmpletpletpletpleteeee FeFeFeFestistististivvvvalalalal Walkden Miles by PPrreeviewview IInsnsiidede PPPPrrrreeeeviewviewviewview IIIInsnsnsnsiiiidededede photos WinWin aa pairpair ofof All weekendweekend tickets!tickets! NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 photo: Miles Walkden FELL CITY GIRL are set to perform at this year’s NEWNEWSS Carling Weekend: Reading Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU and Leeds Festivals. The former Nightshift cover Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] stars, who are unsigned but have been earning themselves an enviable reputation on the local gig SUPERGRASS return with a new For Treatment, Richard Walters circuit and in London, th album and single in August. ‘Road and Smilex, and Sunday 4 have been picked to play To Rouen’, the band’s fifth studio September, which will be a launch on the Carling Stage, th album, is released on the 15 party for The Evenings’ new CD, which aims to showcase August. A single, St Petersburg’ with support from The Family the best up and coming th precedes the album on the 8 Machine and Fell City Girl. acts around. The band will August. be the second act on the AVID RECORDS could be forced Carling Stage on Friday at THE PORT MAHON is set to to close after Oxford City Council Reading (August 26th) and continue, and expand, its live music imposed a backdated rent increase Saturday at Leeds (27th). output with the arrival of a new that could see the shop faced with They will share a stage manager, John Russell-Smith, this a 50% hike in its rent. -

May Oxford’S Music Magazine 2017

[email protected] @NightshiftMag NightshiftMag nightshiftmag.co.uk Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 262 May Oxford’s Music Magazine 2017 “Nothing beats reggae in the sunshine, they were meant for each other.” ZAIA Oxford’s reggae stars bring the summer. Also in this issue: Introducing LOWZ ISLANDAIA COMMON PEOPLE previewed plus All your Oxford music news, reviews and gig listings for May NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshiftmag.co.uk IRREGULAR FOLKS Summer their new `Live at the O2’ EP. On Session returns in July. The one- the 11th Little Brother Eli preview day celebration of music taking their headline show at the O2 an unusual twist on folk music, Academy on the 19th, while singer- takes place at The Victoria Arms songwriter Natureboy launches his RIDE play their biggest hometown show in 25 years this summer. The in Old Marston on Saturday 1st new album instore on Sunday 14th. reformed Oxford pop heroes will play at The New Theatre on Monday July. The event, sponsored by The On Thursday 25th Australian singer 10th July, a quarter of a century on from their sold-out show there in Arts Council, will take place in a Emily Barker will play a set of February 1992. bedoiun tent in the pub grounds songs from her new album `Sweet Tickets for the gig went on sale on the 21st April and are likely to have and again be hosted by comedian Kind of Blue’, while on the 18th sold out within a few days. -

The Small Guys

[email protected] @NightshiftMag nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month NIGHTSHIFT Issue 230 September Oxford’s Music Magazine 2014 photo:Johnny Moto THE SMALL GUYS OXFORD DUPLICATION CENTRE A CELEBRATION OF [email protected] Office: 01865 457000 Mobile: 07917 775477 OXFORD’S INDEPENDENT Supporting Oxfordshire Bands with Affordable Professional CD Duplication PROMOTERS FANTASTIC BAND RATES with ON ALL SERVICES Klub Kakofanney, Gappy Tooth Professional Thermal Printed CDs Full Colour/Black & White Industries, Bossaphonik, The Haven Silver or White Discs Club, Skeletor, All Tamara’s Parties, Design Work Support Digital Printing Black Bullet Live, Empty Room, Skylarkin’ Packaging Options Fulfilment Soundsystem, Daisy Rodgers Music and Recommended by Matchbox Recordings Ltd, Poplar Jake, Undersmile, Desert Storm, Turan Audio Ltd, Nick Cope, Prospeckt, Paul Jeffries, Alvin Pindrop Performances. Roy, Pete The Temp, Evolution, Coozes, Blue Moon and many more... NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 Count Skylarkin (centre) with fellow Disco Shed proprietor NEWS Paddy Bickerton and Channel 4 presenter Max McMurdo Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net this year should apply via the Oxford City Festival page on Facebook. JOHN OTWAY teams up with Wild Willy Barrett for the first time in years when they perform together at the Old Fire Station on Thursday 9th October as part of a tour to THE DISCO SHED has won the Best Normal Shed prize in Channel 4’s promote Rock and Roll’s Greatest annual Shed of the Year Awards. The travelling shed-based soundsystem Failure: Otway the Movie. -

Clashfinder General :: Glastonbury 2011 Clashfinder

Glastonbury 2011 Clashfinder - Wednesday 22nd 09:00 10:00 11:00 12:00 13:00 14:00 15:00 16:00 17:00 18:00 19:00 20:00 21:00 22:00 23:00 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 06:00 07:00 Paddy Havana Claude Matt Andersen Alpha Manoeuvre Bourbon Street Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon MilnerStreet - BourbonSwing Street - BourbonBourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street - Bourbon Street 17:00 - 17:45 18:00 - 18:45 19:00 - 19:45 20:00 - 21:15 21:30 - 23:15 DJ: 200 Watts Bennet NYC Downlow NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC Downlow - NYC 20:00 - 00:00 00:00 - 01:00 TNT DJs, pole stars, cocktails! The Snakepit The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - The Snakepit - 19:00 - 03:00 Andrew Kerr Michael Spirit of 71 Café Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit'Intolerably of 71 Hip' Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - SpiritEavis of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café - Spirit of 71 Café -

Snail Mail: 10 Kingston Road, Oxford OX2 6EF DAILY Email: [email protected] Line Ads@40P/Wd

Queries: 553377 (Mon-Fri 9-5) Oxford’s Adverts: 554444 or via our website: www.dailyinfo.co.uk Snail mail: 10 Kingston Road, Oxford OX2 6EF DAILY Email: [email protected] Line ads@40p/wd. (min.10) + VAT Display boxes@£10/cm. (min 3) + VAT www.dailyinfo.co.uk INFO Graduate Recruitment boxes@£15/cm + VAT Daily Information: daily issues Tue, Thu, Sat in Oxford University term, Fridays in the vacation JOBS OFFERED HOUSES & FLATS TO LET www.dailyinfo.co.uk Next issue: Sat 28th May Electronics Designer Luxury Hotel Barge Issue No. 7610 Deadline: 10am, Fri 27th May 1 BED FLAT, COWLEY. Summer Job Needs houseproud host/hostess Only 6 months old. Double glazed, gas C/H, to live aboard until end October. Do you have a To work on PIC based project in Home Automation all appliances, parking and bike shelter. Thu 26th - Fri 27th May 2005 (5th Week) background in hospitality and speak fl uent English? sector. Good Rates. Based between Thame and High standards required for rewarding job. Band A council tax! £610 pcm + bills. Oxford. PIC programming WHAT’S ON/COMING SOON View www.bargecruising.com / 01491 641237 No smoking or pets or DHSS. Details: [email protected] and email CV to [email protected] Neil 07977 140946. TONIGHT (THURSDAY 26 MAY), 6:00 pm. MAGDALEN COURSE LEADING TO LEVEL 1 TEACHING (SWIMMING) COLLEGE. SOLEMN EUCHARIST FOR CORPUS July 24-29 (01865) 240476 jessie.thomas@sport. CHRISTI, the day of Thanksgiving for the gift of ox.ac.uk AGRIVERT require a Holy Communion.